Exist Yesterday: #Let5D0It, Week Seven

The last of my blurbs on “favorite singles 1954-1976” from my blog. Thanks for reading along, if you have.

8. Sam & Dave, “Hold On! I’m Comin’” (1966)

(Hayes/Porter) prod. Jim Stewart

Stax 189 | #1 R&B, #21 US

“Call my name, yeah, for a quick reaction, yeah-ha YEAAHHH”

Let’s get this out of the way first: fuck The Blues Brothers (1980) as a staff, record label, and as a motherfucking crew. Rich white comedians paying tribute to the music of black Southerners is somewhat inevitable, and ultimately bearable in limited doses — Woody Allen’s dixieland jazz, Steve Martin’s banjo stomps, Hugh Laurie’s piano blues — especially when it ends up pointing people back to the originators of the music. But the soul-destroying thing about cult classic movies is that they end up being prisons of solipsism instead of slipstreams in dialog with the broader river of culture. A generation that seemingly only ever experienced Southern soul and blues (not to mention Cab goddamn Calloway) through the prism of a shaggy Saturday Night Live spinoff, and constantly feels the need to interpose it between the actual music and their own ears, mind, and limbic system is all the more noxious to me because it’s my own generation. So then. Once you divorce the music from a couple of schlubs in sunglasses, black ties and porkpie hats, what’s left? A universe: from the lyrics’ passionate declaration of steadfastness to the way both men seem to sing with not just one voice but one mind, trading off shouts and exclamations live as crisply as sample-based music would electronically, “Hold On! I’m Comin’” is such a towering masterpiece of the Stax sound that it feels almost etched in granite rather than vinyl or acetate. Some of Al Jackson’s most powerful drumming, Steve Cropper’s wickedest barbed-wire guitar solo, and the Mar-Key horns erecting vertiginous backdrops against which Sam Moore and Dave Prater act out a volcanic passion play from the very depths of their vocal chords. No amount of Hollywood bombast could improve the crackling electricity of two men who hated each other but were locked into a partnership by the chains of success forged by singing their hearts out about being your joint salvation. Otis Redding, Wilson Pickett, and a half-dozen other Stax stars could perhaps have been here instead; but nothing shoots to the heart like Sam & Dave.

First encounter: I heard “Soul Man” on oldies radio first, I think, and then when I looked it up I also downloaded the other high-seeded Sam & Dave mp3. Aft first I liked “Soul Man” more because the tempo is slightly faster and it does the terrible 1967 cliché of namechecking Woodstock, so it felt Important; but I was soon beguiled by the more working-class grit of “Hold On,” not to mention an arbitrary kind of pop originalism that favored earlier, first-big-hit work over later flourishes. And every time I’ve listened since has only confirmed it.

7. Dolly Parton, “Jolene” (1973)

(Parton) prod. Bob Ferguson

RCA Victor APB0-0145 | #1 C&W, #44 EL, #60 US

“Your smile is like a breath of spring, your voice is soft like summer rain”

Few songs eligible for this list have been more memed about on social media for the past few years, which for any less sturdily-constructed song (say “Hallelujah” or “The Devil Went Down to Georgia”) would put it in danger of all meaning being leached out of the song itself in favor of the broader Discourse About the Song. (This happened a decade ago with “Baby, It’s Cold Outside,” for example.) But the thing about “Jolene” is that it never feels like a cliché no matter how familiar you get with it. Part of that is Dolly rooting it in the minor scale, so that it has a haunting quality at odds with the comfort and familiarity of so much of its contemporary work, but the lyrics are equally haunting. Not just the “it sounds like she’s as into Jolene as her man is” queer reading of which much has been made in recent years, but the phrasing itself is so old-fashioned that it is nearly a credible facsimile of something A. P. Carter might have dug up from a nineteenth-century Folk Songs of the Hills, if Dolly’s problem with the possibility of romantic betrayal wasn’t so focused on the emotional devastation of the wronged woman rather than the moral turpitude of the vamp and her victim. Indeed, the fact that the song doesn’t cast any kind of judgment on Jolene for being a temptation, only pleads with her as between equals, makes it a sneakily feminist song despite not passing the Bechdel test (lol).

First encounter: Dolly Parton was one of the few secular musicians I had any awareness of as a child in the 1980s, although I often confused her with Tammy Faye Bakker, who occupied a similar aesthetic position in an area of culture I didn’t understand and felt weird about identifying with. (My parents were fundamentalist evangelicals but skeptical of televangelists, and too aspirationally-educated for country even if secular music had been permissible.) In fact I don’t think I had ever consciously heard a Dolly Parton song until 2001, when I read music reviews for Little Sparrow that made it one of the first hundred CDs I ever purchased. Backtracking to pick up on her previous career highlights introduced me to “Jolene,” and I was taken with its spare, almost skeletal production (for early-70s country, anyway) from the start. It’s been with me ever since.

6. David Bowie, “Young Americans” (1975)

(Bowie) prod. Tony Visconti

RCA 2523 | #28 US, #18 UK

“We live for just these twenty years, do we have to die for fifty more”

The last performer on my list that could conceivably be framed as a white rocker, and the specific choice of song is a deliberate attempt on my part to chip away at any white rock consensus that might threaten to form around him. Not that I don’t love, say, “I Dig Everything” or “Space Oddity” or “Changes” or “Starman” or “Life on Mars” or “Rebel Rebel” or “Fame” or anything else more firmly rooted in rock (whether glam- or art- or unhyphenated) that might accrue momentum in the larger poll, but the plastic soul of “Young Americans” is so specific and even controversial (although not perhaps within the self-selecting group who would join a project like this) that nearly anyone for whom it is their favorite David Bowie track has loads of non-plastic soul they would put ahead of it. Luckily, I happen to really love “Young Americans” too — on the morning eight years ago when I woke up to the news of his death, it was the aching falsetto “ain’t there one damn song that can make me break down and cry-hyyyy” that caused me to do just that on the train into work while listening through an in-memoriam playlist of his major songs. Anyway, Bowie being the supreme rock artist of the 70s is a commonplace enough take that it’s worth disrupting a little; while Bowie being the supreme white male artist of 1954-1976 is in no sense a defensible take, but I was amused enough to see that it’s what my ranking ended up suggesting that I’ve let it stand. The cocaine-addled logorrhea of the lyrics is hardly worth analyzing, although as with all Dylan acolytes it’s not the whole but individual lines that matter — the real craft at work is Visconti’s, shaping an ill-conceived meditation on racially-stratified generational change in the U.S. (the kind of thing no self-respecting American, young or otherwise, would normally tolerate from any twitchy Brit) into a grooving hustle, with rock-solid backing vocalists, including Luther Vandross, lending a steady arm to the gibbering thin white duke to lean on. The fact that it’s the single that gave Bowie his biggest U.S. hit since the campy sci-fi melodrama of “Space Oddity” is just gravy.

First encounter: I picked up the Changesbowie CD early on in my infatuation with music history, and it has remained the spine of my Bowie understanding since. Although I have certainly listened to most of the canonical Bowie albums, he remains primarily a singles artist for me (along with the occasional frequently-spun album track); it’s the pop chameleon, not the art rocker, much less the glam rocker, that I fell in love with, and since I have come to think of soul music, plastic or otherwise, as more interesting and vital than statement rock, his attempts at black-inflected dance music have consequently risen in my esteem.

5. The Supremes, “Where Did Our Love Go” (1964)

(Holland/Dozier/Holland) prod. Brian Holland, Lamont Dozier

Motown 1060 | #1 R&B, #1 US, #3 UK

“I’ve got this burning, burning, yearning feeling inside me”

It’s the foot stomps, rigged up to wooden boards so they land sharper and harder than regular footwear could, that grab you first. It almost sounds at first like a tap-dancing chorus line, one of the key sounds of modern industrialized entertainment for the previous generation. But within two bars, Earl Van Dyke’s piano, James Jamerson’s bass and Diana Ross’s voice, lower than she wanted to be singing, enter in unison: “Baby, baby.” There is probably a whole dissertation or more to be written about the use of that particular endearment in pop music, a self-conscious infantilization through which a constructed evocation of eternal youth is endlessly refracted — but in the moment, what you hear is the sensuous thrill of Diana’s voice, and the intimacy with which she, and the rest of the Supremes, and Holland/Dozier/Holland, and the Funk Brothers, and Motown as an institution, has addressed you, and you’re already half in love with her, and all of them, because of it. The rest of the song is just an elaboration: she’s begging you not to leave, but not in a voice of urgency. Diana Ross was not, despite her place at the center of Motown, a soul singer: her pretty, silky voice was made for jazz-pop, and in another world she’d have been a Nancy Wilson or Dionne Warwick, even a distaff Johnny Mathis. But whether because of the genius vision of Dozier and the Holland brothers or because Berry Gordy had a thing for her, pushing her to the forefront of the Supremes was exactly the formula Motown needed to split the difference precisely between R&B and pop, with an effect nearly as big as splitting the atom. There were nearly a dozen great Supremes singles after this one, any one of which could have vied for this spot, but my unreasonable loyalty to firsts keeps “Where Did Our Love Go” close to my heart.

First encounter: One of the glories of oldies radio around the turn of the millennium was that it consistently played mid-to-late 60s Motown. If I had had a normal childhood with a normal level of exposure to the popular music of my parents’ youth, I might have rolled my eyes and turned the dial too, as my friends did; but I had not, and so every three minutes was a new revelation, at least for a while. Even so, I had never sat down to listen to the Supremes as the Supremes, rather than as a thread in a bygone tapestry, until the Pitchfork 60s list, with five Supremes songs equalling the Beatles’ count drove me to listen to them more carefully, and I realized just how incredibly gorgeous and singular those records were.

4. Howlin’ Wolf, “Smokestack Lightnin’” (1956)

(Burnett) prod. Leonard & Phil Chess, Willie Dixon

Chess 1618 | #11 R&B, #42 UK

“Whoa-oh, stop your train, let a poor boy ride”

The last rock song on the list is hardly a rock song at all, and hardly even a blues song, sounding somehow older and more primal than either. But just about every throat-shredding white boy who ever tried to bellow with authority and mystique into a microphone was imitating either Howlin’ Wolf or someone who was imitating him. Although that deep dark croak of a voice, the bedrock of masculine gruffness in the pop sphere was not necessarily original with Chester Burnett — Charley Patton and Son House were his forebears in bellows that seemed to come from deeper than a human body can resonate. But the movement of the Delta blues up the Mississippi, where they electrified and where a couple of Polish Jews who changed their last name from Czyz to Chess discovered, or invented, a national market for black men with guitars and harmonicas hollering darkly about such eternities as lust, loss, pain, and trains, is part of the creation of rock and roll itself: Chicago, just as much as Memphis, New Orleans, or any other breeding ground, is where rock was born. But on “Smokestack Lightnin’,” it’s not Howlin’ Wolf’s gutbucket roar that stays with you, but the mournful, wordless howl ending every stanza: “awoo-hoo, awoo-hoo-ooo-oo-ooo-oo.” Vulnerability, sorrow, regret, ache: these are at the heart of the blues, and to the degree to which rock borrows only the badass posturing and not the lacrimae rerum, the tears that are in all things, rock is lesser than the blues.

First encounter: Once more, from end-of-the-century lists, I believe. Although it’s hard to remember: I dug with equal fervor into 50s rock & roll and 60s British Invasion and 20s jazz/blues and 80s new wave in 2000 and 2001 and although each decade was siloed off from each other in those early researches, I was at least aware enough to dump electric blues into the same bucket as rockabilly, swamp pop, and New Orleans R&B. “Smokestack Lightnin’” emerged early as my favorite Chicago blues song, thanks to its evocative title if nothing else — apologies to godheads like Muddy Waters, Bo Diddley, Sonny Boy Williamson, Junior Wells, etc., but there just wasn’t enough room.

Label image via Discogs

3. Martha & the Vandellas, “Dancing in the Street” (1964)

(Gaye/Stevenson/Hunter) prod. William Stevenson

Gordy 7033 | #8 R&B, #2 US, #28 UK

“All we need is music, sweet music, there’ll be music everywhere”

One thing about being raised in a fundamentalist evangelical bubble from infancy is that you are always primed for the eschaton. Any use of the future tense, so long as the details are fuzzy enough, can be about the end of the world, and whether it’s a jubilation or a lamentation hardly matters since both have been accounted for in your secondhand philosophy. And so there’s a sense in which I have always heard “Dancing in the Street” as apocalyptic (\pos), or as one Professor Tolkien would have it, eucatastrophic. That opening drum crash might well be the crack of doom; the triumphant fanfare that follows could be blown by the angels of Revelation. The street in which we’ll be dancing is a street of gold (Rev. 21:21) — and in fact there’s no friction between this reading and the more typical Civil Rights reading as a call to civic unrest to agitate for equality, because by the time I was paying attention to pop music I was no longer evangelical but Catholic, and liberation theology was the preferred metric by which I squared my lingering religiosity with my increasingly strong social conscience. So I now understood the ending of oppression as being always the end of one world and the entrance into a new and better one, and the centrality of celebration to Martha Reeves’ summons to convocation was just another representation of the Jubilee (understood both in the typical sense of festivity and in the original Leviticus sense of forgiveness of debts, liberation of the bound, abolishment of private property) at the heart of all struggle for a better world. Which is a lot of words to say that every time that Martha and the Vandellas’ “Dancing on the Street” came on the radio between 2004, when I had absorbed enough ambient awareness of Motown to hear it properly, and 2012, when I stopped driving and so effectively stopped listening to the radio, I could not keep from crying. It is also why I loathe loathe loathe the Jagger/Bowie version, because watching two wealthy white middle-aged Londoners prance ghoulishly about at the zenith of Reagan and Thatcher, mumming someone else’s prayer, is enough to very nearly put me off British music for good.

First encounter: Like a lot of this list, I couldn’t say when I first heard it, only that by the time I was paying close attention to it I was already familiar with it. I was almost certainly in my car, though; two decades of driving to and from jobs, events, churches, and shops in the greater Phoenix metropolitan area gave me a lot of time with the radio on. I don’t think I’ve ever listened to it without turning up the volume: apparently part of the pounding percussion is co-composer Ivy Jo Hunter smacking a tire iron, and that’s the kind of assault it should always have.

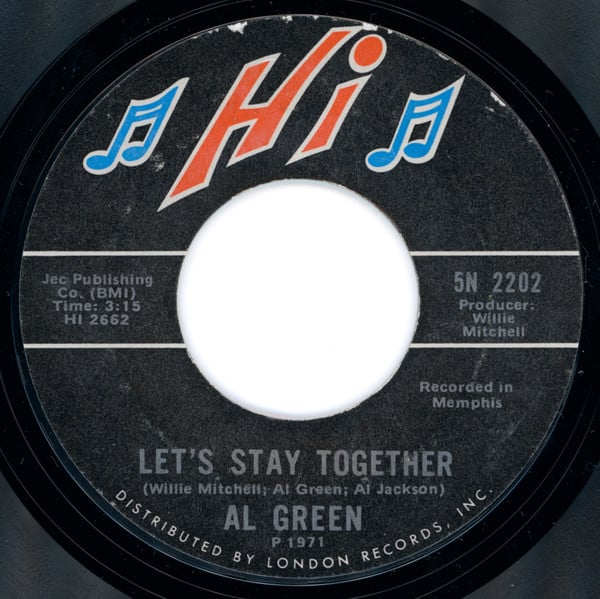

2. Al Green, “Let’s Stay Together” (1971)

(Green/Mitchell/Jackson) prod. Willie Mitchell

Hi 2202 | #1 R&B, #1 US, #7 UK

“You-ou’d never do that to-oo me-eeee-eeee, wouldja baby”

If he had been born ten years earlier he might have been a jazz singer instead of a soul singer; twenty years earlier and he definitely would have. In some ways his relaxed, expressive, intimate vocal style is the very opposite of what jazz singing had become in the meantime, with its cool, distanced intellectualism and rigorous technique — but Green’s loose, highly improvisational approach to his own material, although ultimately descended from gospel rather than jazz, is so immaculate in its phrasing and tender in its sympathies that I hear resonances with Fats Waller and Louis Armstrong as much as with Otis Redding or (the most obvious antecedent) Marvin Gaye. The Reverend Green doesn’t shout or storm, tearing words from his throat with hard-won intensity: he glides, he teases, he cajoles, he slips into a falsetto and trills. There’s a whole category of R&B descended from his early-70s oeuvre: baby-making music. But of course it wouldn’t work without Willie Mitchell’s smart, equally subdued, equally horny production. Mitchell’s early instrumentals, little unheard masterpieces of soul-jazz, stood him in good stead when it came to orchestrating Al Green’s soft-spoken but casually intense R&B. The crackle and strut of classic Stax wouldn’t do at all: a sparse arrangement with plenty of room for Green to stretch out in, horns punctuating his thoughts rather than delivering a riff, and cantering drums keeping an even keel make it almost an easy-listening track, if a middle-aged easy-listening housewife could listen to the purr in Green’s throat and not break into a flushed sweat.

First encounter: I must have listened to it when I was first building my 1972 canon, since the album of the same title was released in 1972, but my first real memory of Al Green — aside from as a sexy-music namecheck on That 70s Show — is cuing up “Let’s Stay Together” at my desk at the bad job and finding myself confounded by the way his performance elongated and danced around the words and notes, sliding from verse to chorus in a way that meant I could barely pick out the structure of any given line, let alone the song. It’s been twenty years, and I’ve become much more familiar with post-60s R&B practice since then, but the memory of that confused first listen has stayed with me always. My initial soul education had been centered on the pop strictures and foursquare certainties of Stax and Motown; this slinky, sexy, post-What’s Going On? groove (but without a thought to spare for the wider world, just your emotional and sensual state) was something new on my horizon. I’ve since learned how omnipresent it has been for everyone else this whole time, and I can’t help feeling a little sorry for them: if you can manage it, I always recommend coming to a very popular piece of music brand new, with adult faculties, on its own terms, without the mediation of film, television, or a commercial retail environment to distract you and let it seep in in the background.

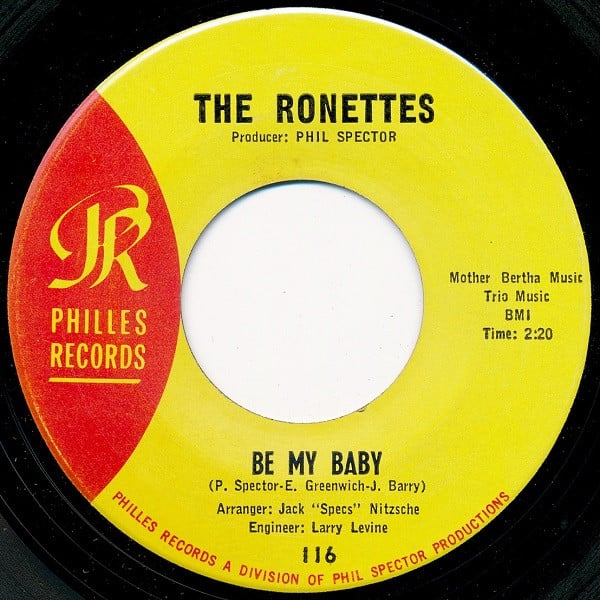

1. The Ronettes, “Be My Baby” (1963)

(Spector/Greenwich/Barry) prod. Phil Spector

Philles 116 | #4 R&B, #2 US, #4 UK

“For every kiss you give me, I’ll give you three”

Dun. Da-dun DAH. Dun. Da-dun DAH. Shakers, piano, guitar, castanets, and miles and miles of echo. Then her voice comes in: a little nasal, a little tough, a Washington Heights girl who’d just as soon be chewing bubble gum and flicking her heavily winged eyes uninterestedly over you while leaning coolly against whatever surface is most convenient, but no instead she’s standing here making a confession. She loves you, she wants you, she needs you. The words are conventionalized, banal, cheap jukebox poetry. The crack in her voice, the hint of hoarseness in the back of her throat, is real. Strings swirl up, other voices sashay in and sing ooh-ahh-ooh’s behind her. The music swells, towers and crashes like a tidal wave. She’s nineteen years old and she wants you to be her baby.

She’s twenty years old and she’s being arrested for prostitution after leaving her producer’s hotel room. “The night we met I knew I needed you so.” She’s twenty-three and her paranoid, jealous producer boyfriend won’t let her go anywhere near the Beatles on their final concert tour, so her cousin takes her place in the opening act. “We’ll make um turn their heads every place we go.” She’s twenty-four and the hits have dried up but she’s marrying famous record producer Phil Spector at City Hall at the insistence of her mother, who has never been happy about their live-in arrangement. “You know I will adore you till eternity.” He keeps her a prisoner, entombs her career, threatens to kill her and put her body on display in a glass coffin if she ever tries to leave him. “And if I had the chance I’d never let you go.” She’s twenty-nine and running barefoot from a razor-wired, security-guarded, camera-surveilled mansion in Beverly Hills. “So come on and please.” She’s thirty-one and signing away all future record earnings so she can be divorced from a glowering monster. “Be my little baby.” She’s fifty-nine and the New York State Court of Appeals determines that she is, in fact, entitled to a share of royalties from her recordings. “Say you’ll be my darlin’.” She’s sixty and her ex-husband kills an actress he had met earlier that day in his home. “Be my baby now.” She’s seventy-seven and he dies of COVID-19 in prison. “Woah-oh-oh-oh, ohhh ohhh ohhh.” Almost exactly a year later, cancer takes her too in her Connecticut home, surrounded by loved ones. Dun. Da-dun DAH.

The diabolical entwining of Veronica Bennett’s life with and by the man who produced her most famous and beloved and, not to overstate anything, immortal work is one of the great tragedies of pop, the equal of the crash of plane N3794N or any overdose at the age of twenty-seven. The Ronettes’ pre-Philles singles are undistinguished but lively; Phil Spector’s often-repeated (and widely believed, even by pop fanatics) claim that he plucked them from obscurity and made them the stars that their lack of talent and ability never could have is not just transparently self-serving but entirely belied by his obsessive efforts to prevent Ronnie from existing and especially recording outside of his sphere of influence. That voice, limited and even fragile as it was, and even more her tender-tough image and persona, belonged to her, never to him, and it was not (just) the Spector production that made Brian Wilson, George Harrison, Bruce Springsteen, Billy Joel, and Joey Ramone want to write songs for her to sing. If history had slid into a different groove, if the Ronettes had recorded “Don’t Worry Baby” in 1964, gotten out of their contract with Spector, been allowed to grow and change and explore even in the restrictive ways that the similarly trapped Tina Turner was instead of being frozen eternally in a diorama labeled 1963–65, if Ronnie had been allowed not just the packaging but the support that Diana Ross or Dionne Warwick got in the Sixties — ah, what’s the use of what ifs? Ronnie was a mixed-race working-class “bad girl” from the hood, not a middle-class church girl from the Garden State or the Midwest. Anyway, she got forty-three years of a solo career after wresting herself loose from Spector’s clutches, and since her legion of fans included some of the most famous and influential people in popular music, she never had to go begging to the oldies circuit. Her last record was released in 2017, a day before her seventy-fourth birthday.

Phil Spector was not the first abusive man to assume credit for the success of a young woman singer (the Svengali archetype of the 1890s resonated as much for its universal recognizability as for its antisemitism), nor would he be the last. But because pop attracts myths, and the myth of the “genius” behind the Wall of Sound is a persistent one, thanks in great part to Spector’s own self-aggrandizing promotion, he has come, especially in the last twenty years, to represent a kind of poison at the heart of pop, if not of entertainment itself. There is a very real sense in which the old colonialist canard of the uncivilized tribe who ritually sacrifices a virgin to ensure a bountiful crop is in fact true of the modern global entertainment industrial complex, that the lives and hearts and hopes of thousands if not millions of young women (and worse still, children) must be broken upon the recklessness, appetite, and egotism of powerful and money-making men in order for the sausage to continue to grind, that any amount of sexual and physical and psychological abuse is worth a brilliant music career or a beloved television institution or a raft of Oscar nominations or even just a D+ standup career. In the foregoing pages I have praised the work of many people who I know have done awful things, and I am sure many more of whose sins I remain ignorant. But then few of their sins are as embedded into the fabric of the music as Spector’s.

Anyway. Phil Spector is no more single-handedly responsible for “Be My Baby” than David O. Selznick is for King Kong. Jack Nietzsche’s orchestrations, Larry Levine’s sound engineering, Sonny Bono’s production assistance, Hal Blaine’s drumming, and dozens of other instrumentalists, singers, and studio rats — Cher is in there somewhere — are the ones who built the wall. And none of it would work without the teenage girl trembling with nerves who had been practicing her woah-oh-ohs in the studio bathroom minutes before. Even the song itself has never been convincingly covered in any mode but the explicitly nostalgic; without either the massive sweep of the Wrecking Crew or the small pleading voice at the center of the hurricane, it’s a trifle, one of the least in the Greenwich/Barry canon.

Which is what makes it perfect pop. It can’t be anything else but a record. Try it in any other context — the Act 1 curtain of a jukebox musical, the bones of a jazz workout, electronically retooled into a disco or techno or EDM banger — and it simply won’t work. The stop-start heartbeat rhythm (Dun. Da-dun DAH) that introduces and, at the climactic middle eight, interrupts it makes it impossible to dance to, and even the main section is too slow and stately; rhythmically, it has more in common with “Pomp and Circumstance” than “Twist and Shout.” But cue it up again and it takes the breath away all over again. Brian Wilson spending the entirety of the 1970s playing it over and over again in a marijuana fog is a cautionary tale but a tempting or at least an understandable one. If you could just crack it open a little bit more widely, maybe you could fall into that world, and Ronnie would be singing not to the generalized “you” of pop-song convention, but to you, specifically, forever and ever.

First encounter:

In 2003, at the automotive filing job, I listened to the only in-print CD available to me, ABKCO’s 1992 Best of the Ronettes, on headphones and found it muffled and thin, at complete odds with how Spector’s Wall of Sound was described by reviewers and critics. I had better luck getting lost in Spector’s Righteous Brothers productions, but the girl-group stuff, frozen in amber by two legendary music-biz assholes, sounded airless and shriveled compared to the compression-maxing reissues I was listening to otherwise.

In 2004, at the bad job, I was checking Pitchfork’s Tracks column daily and downloading whatever sounded interesting. Liverpool indie-pop band Johnny Boy’s “You Are the Generation That Bought More Shoes and You Get What You Deserve” cropped up there; I liked it, it became part of my regular listening. The heartbeat drum intro (Dun. Da-dun DAH) sounded familiar; but I associated it with their tinkling widescreen kitchen-sink pop and thought no more about it.

In 2005, Danish noise-pop duo the Raveonettes, whose Jesus and Mary Chain (Dun. Da-dun DAH.) cosplay I knew and liked from Pitchfork reviews, released their second album, featuring an aging Ronnie Spector on “Ode to L.A.”. That, implausibly enough, was when everything finally clicked into place, and I suddenly understood Bruce Springsteen’s and Elvis Costello’s “woah-oh-ohs” as the tributes to Ronnie they always were. I became obsessed with her post-Ronettes work, and still count “Try Some, Buy Some” and “Say Goodbye to Hollywood” among my favorite relatively obscure pop treasures.

In 2006, Rhino’s One Kiss Leads to Another: Girl Group Sounds Lost and Found tempted me from the Tower Records box set pile, but I couldn’t ever justify the expense. Still, it nagged at me: why did pop music by and for young women have to be rescued from oblivion and have a case made for it when the boy bands of the same era (whose music I had already internalized half a decade ago) were endlessly reissued and kept in print and had their own dedicated rows in the same store?

In 2007, I took a solo road trip to L.A. to catch two shows: the release party for Paul F. Tompkins’ Impersonal at the UCB and the Pipettes at the Troubadour — the Pipettes (also introduced to me by Pitchfork) were my new favorite band, a blend of irony and sincerity, camp and reverence, nostalgia and modernity. “Girly music,” as I was still kind of calling it in the back of my head, was becoming increasingly central to my understanding of pop.

In 2008, I found myself beginning to listen less and less to the oldies and classic-rock stations and more and more to the current pop and R&B and hip-hop stations, not sure how to assimilate what I was hearing because it was so different from the classic pop (and classic-pop-inflected modern indie) I had been soaking in for nearly a decade, and I kept reminding myself that there were young women out there listening to the radio too and loving this music desperately and that they deserved as sympathetic a hearing as the young women who had bought Ronettes and Crystals singles in 1963. And so I taught myself how to love contemporary pop, just in time to ride a new wave of brilliant chartpop by and for young women: Gaga, Ke$ha, RiRi, Nicki, Katy, Taylor, Miley, Carly Rae, and more beyond, until the tide shifted and sleazy men reasserted chart dominance once more.

In 2009, I started posting on Tumblr and found myself part of a thriving music-critic discussion ecosystem, which has continued on Twitter and newsletters and Bluesky and wherever else it must go next.

In 2012, when Spotify came to the US, I learned that the Spector library had at last been remastered to compete with contemporary standards.

In 2021, my second most popular tweet ever was about “Be My Baby,” the day after Phil Spector’s death.

In 2024, the first thing I did after making a list with 50 entries was to put “Be My Baby” at #1. Dun. Da-dun DAH.

Next week: 50 lists of 50 singles that could have made this list instead. I’m still finishing up a bunch of those, so they’ll most likely hit the blog at the same time they go out in email. And stay tuned for a similar project covering 1977-1999 singles in the fall and then (the one I’m really jazzed about) pre-1954 singles in the new year. But I’ll try not to remain incommunicado until then.