Exist Yesterday: #Let5D0It, Week Two

Continuing my recap of the daily blog posts I've made this past week; see my previous newsletter for details.

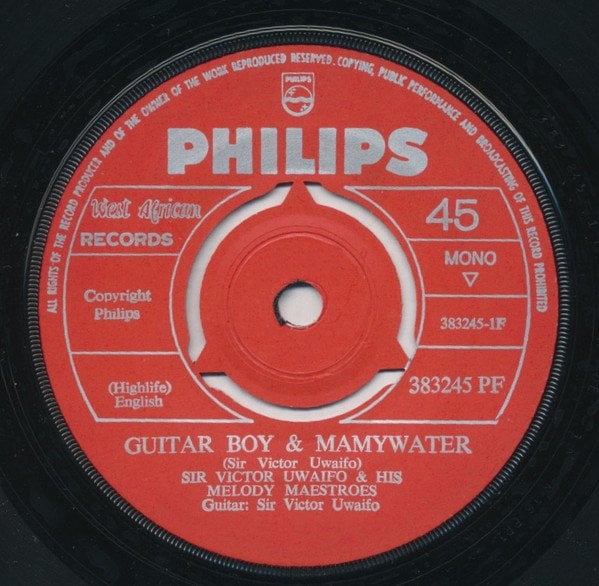

43. Sir Victor Uwaifo & His Melody Maestroes, “Guitar Boy & Mamywater” (ca. 1969)

(Uwaifo)

Philips 383245 | did not chart

“Sing that song of love, sweet melody”

It is to my shame that this is the only African record on this list, all the more so as African music has become central to my 21st century listening. My only excuse is that it is the African song of the period that I’ve known the longest and so had the most time to fall in love with. But it is also an object lesson in the erratic recordkeeping of global music history: although several online sources will tell you that the most widely available version of this song, a 5:44 workout featuring some creative wah-wah effects, dates to 1966, a transmission error I too have been guilty of, my closest research has not been able to date it to earlier than a 1980 LP in which Uwaifo and his then-band the Titibitis present his old hits with an updated, funkified sheen. The actual single, which I finally got hold of a copy of last week, and which comparison with other label issue numbers appears to date to some point between 1968 and 1970, was also issued on the EP Dancing Time No. 8 around the same time. However, the existence of the song on record circa 1966 is attested by the fact that a failed 1967 military coup in Ghana was called Operation Guitar Boy after the song, which was being played continuously on Accran radio at the time, so my dating of it to 1969 is only provisional. In any case, the record I own is a much more laid-back affair than the pedal-frenzied version found on several latter-day “African funk” compilations: it’s straightforward highlife, with bright, pointilist guitar figures and a cool R&B sax break. Victor Uwaifo was a Nigerian highlife singer, guitar player, and bandleader who was hugely successful in the immediately pre-Fela era of West African pop, with a guitar style that would go on to fuse traditional highlife fingerpicking with contemporary currents in rock and soul, which he would call akwete. The lyrics reference his supposedly biographical encounter with a Mami Wata (West African water spirit), which he credited for much of his success: like American bluesmen meeting the Devil at a crossroads, contact with the supernatural is an essential part of musical mythography.

First encounter: In 2006, more as a challenge to myself than for any other reason, I compiled an alternate 200-song list of music from the 1960s as an attempt at a “corrective” response to Pitchfork’s 200 Songs of the 1960s feature. When I went looking for African music to fill P4k’s Bembeya Jazz National slot, Victor Uwaifo was one of the few names I found music available for, and I fell in instant love with the latter-day version of “Guitar Boy” from a Rough Guide to Highlife comp, misdated. It remains one of the few records I discovered while digging around for that project that I still have a lot of affection for, and while the Sixties version of the record turns out not to have been the one I originally fell in love with, I’m almost more charmed by its basic R&B values today.

42. Françoise Hardy, “Le temps de l’amour” (1962)

(Morisse/Salvet/Dutronc) prod. Jacques Wolfsohn

Vogue 1074 | did not chart

“On s’en souvient, on s’en souvient, on s’en souvient”

The usual practice, when discussing the beginning of Hardy’s illustrious career, is to give pride of place to “Tous les garçons et les filles”, because she wrote it herself and it was a #1 hit in France, even troubling the UK charts. But its sugary carousel melody, contrasting in fine irony with the somber, distanced lyrics, has for whatever reason never been as attractive to me as this spare, almost goth cut from the same debut album and co-composed by her future (for a time) husband, with its Bo Diddley beat and a spidery guitar figure that sounds drawn from pseudo-North African harmonic modes. The lyrics are an extremely Gallic piece of nostalgic philosophizing about the impermanence and ecstatic folly of youth, but its abstractions sound that much closer to true in her cool, reserved, and undeniably youthful intonation than in the dozens of rumpled, leering middle-aged men’s voices that could have sung it instead. This is, by the way, the only French entry on my list: no Gainsbourg, Brel, Brassens, Gréco, or Piaf, all of whom I tend to appreciate more situated in historical context than in the immediacy of listening. But Françoise Hardy’s unflappable cool and insistent self respect have never gone out of style.

First encounter: This too, I think, first came up when researching my response list to P4k’s 200 Songs of the 60s, and I used it as a one-to-one substitute for “Tous les garcóns,” over which I feel somewhat embarrassed — yé-yé is a much more diverse and fascinating field than I really understood at the time — but the skeletal bop and doomy production have remained fixed in my mind ever since as a sort of French New Wave approach to pop, using American forms but without any of the roiling passions or dirt under the fingernails that made the American scene so vivid and tasteless.

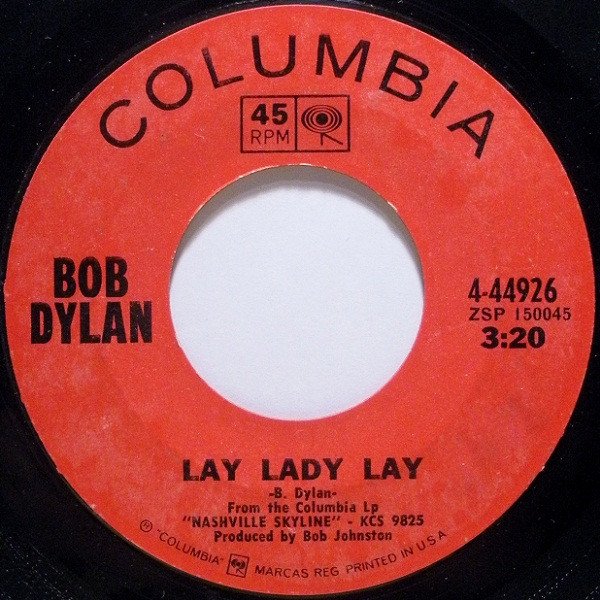

41. Bob Dylan, “Lay Lady Lay” (1969)

(Dylan) prod. Bob Johnston

Columbia 44926 | #7 US, #5 UK

“Why wait any longer for the world to begin”

We have reached one of the major Questions that any attempt to grapple with this era in popular music necessitates. One form that the Dylan Question can take: is the man’s monumental influence on the songwriting patterns of a generation worth having to cope with his voice/ego/misogyny/etc.? There are plenty of cases where I’m happy to dispense with a less-than-sterling character — there are some omissions from my list that it would be difficult to describe as other than vindictive — but I feel compelled to be honest about both the contours of pop history as I understand them and my own emotional history, and admit that Dylan is a sine qua non of twentieth-century pop, a fact that must be dealt with for better or worse: often much worse, especially in the way that his auteurification of pop was used by fans and critics alike as an excuse to deliberately marginalize interpreters, especially women, who failed to write their own material. My own compromise, in selecting an elegant-but-horny ballad with a relatively simple structure over any of his more verbally ostentatious or politically meaningful outings, is meant to take a stand on the side of pop (which includes country) over rock (which overvalues ostentation and meaningfulness). Kenny Buttrey’s tinkling percussion, Pete Drake’s wheedling pedal steel, and Bob Wilson’s buttery organ create a suspended-in-time soundscape in which Dylan’s “new” vocal style, low and croony à la Elvis rather than sharp and reedy à la Woody Guthrie, approaches something like attractiveness. YMMV, of course — and I won’t deny that doing my part to split the Dylan vote in the broader poll was a consideration in my selection. Not to mention that such a large portion of this list is recognizing artists at the peak of their powers and peak commercial conditions; but I’ve also been fascinated by the long tails of major artists’ careers, when every release gets a polite “their best since [fill-in-the-blank]” reception, and Dylan reaching that point before he was thirty is one more way he helped solidify the shape of popular music in the second half of the twentieth century.

First encounter: Aside from a brief dalliance with the Forrest Gump soundtrack in high school, my introduction to Bob Dylan was getting a tape mailed to me in 1998 by a comic-book message-board friend who had been gently appalled by my ignorance of the Sixties classics; I soaked in it while cutting the lawn at my parent’s house during a summer home from college. I think, but can’t be positive, that “Lady Lady Lay” was on that tape; in any case, my first favorite Dylan song was the epic “Desolation Row” (not uninfluenced by how Alan Moore made use of it in Watchmen), and I hovered around the Bringing It All Back Home–Highway 61 Revisited–Blonde on Blonde nexus as all I needed for a considerable time. It wasn’t until years later that I tried out Nashville Skyline and discovered that the pillowy country arrangements exactly suited my more expansive tastes, which were slowly moving out of rock-centrism, as well as being more consonant with the wheezing crooner of Love and Theft that I had fallen in love with in the interim. Discovering one evening in the late 2000s that I was misting up because “Lay Lady Lay” came on the car stereo and sounded more achingly beautiful that I remembered has never quite left my memory.

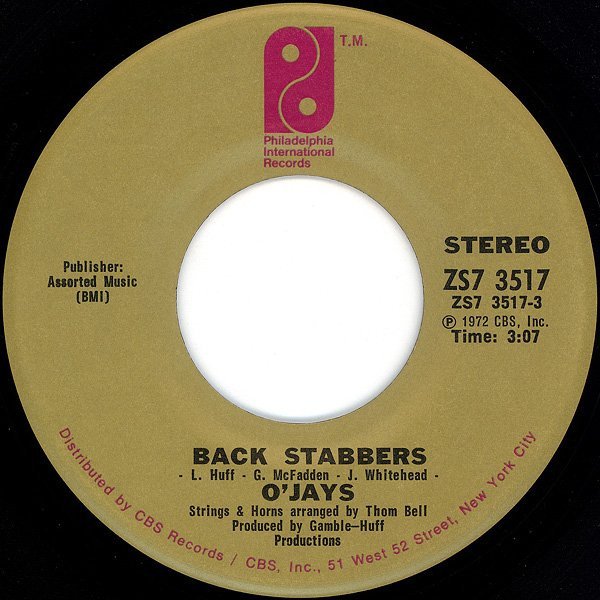

40. O’Jays, “Back Stabbers” (1972)

(Huff/McFadden/Whitehead) prod. Kenny Gamble, Leon Huff

Philadelphia International 3517 | #1 R&B, #3 US, #14 UK

“What can I do to get on the right track, wish they’d take some of these knives out my back”

In a notional poll for Best Pop Song Intros, I would plump hard for the first forty seconds of “Back Stabbers,” Gamble & Huff’s lush Philly update on Norman Whitfield’s mini-symphonies for Motown. That the rest of the song never quite lives up to the drama of that intro, with its rolling piano, insistent cowbell, swirling strings, smoky guitar, and insouciant bassline, is hardly a knock against it: the thesis song they reference in the outro, Whitfield’s own “Smiling Faces Sometimes”, was far more a triumph of production over performance. But Eddie Levert, Walter Williams, and Eric Grant deliver all-time vocal performances, trading off lines like sprinters in an underwater relay as the paranoid machismo of the lyrics builds and builds, struggling against the welter of anti-communitarian untrustworthiness that is the text for the day. As you might expect, I find the overt premise of “Back Stabbers,” that anyone could be plotting to steal your girl from you, politically dubious: but as a Nabokovian portrait of toxic masculine paranoia, inculcated by a society which insists that ownership of a woman with no agency of her own (which also means unable to be trusted) is the primary aspect of manhood, it’s a pocket whirlwind. Why Men Don’t Form Intimate Friendships, exhibit 5,038.

First encounter: The primacy of rock in my initial musical education meant that I came late to R&B and soul, especially if it wasn’t being played on an oldies station; and during my peak years of oldies listening the cutoff was around 1968. I believe I would have first heard “Back Stabbers” on some Rhino compilation of 70s soul or other; but it was when I began digging into the broader soundscape of 1972 that it really got fixed in my heart as one of the great records of the period, and it’s never left there since.

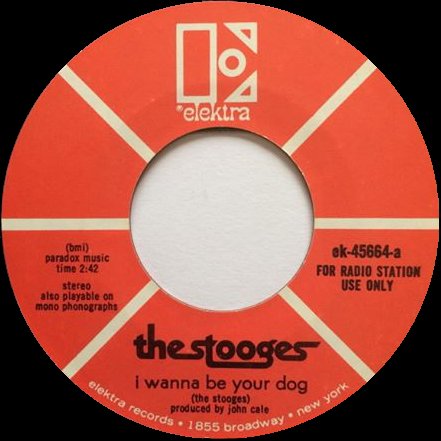

39. The Stooges, “I Wanna Be Your Dog” (1969)

(Alexander/Asheton/Asheton/Osterberg) prod. John Cale

Elektra 45664 | did not chart

“And now I’m ready to close my eyes, and now I’m ready to close my mind”

I feel like I have to walk a delicate line here. Why this song, over “1969,” or “Search and Destroy” or “Raw Power,” or indeed “Kick Out the Jams” or even “Blitzkrieg Bop”? A good question because, I’ll go ahead and admit it now, this is the closest my list gets to punk. Which is maybe more than anything about the headspace I was in when I made it, but it is also a deliberate Stance: loud rock & roll rebellion (or even just loud rock & roll fun, fun, fun) is less important to me at this stage of my life and analytic priorities than a lot of other uses of popular music. But still, I did pick this song and put it here; so if not for punk-rep reasons, why? An easy answer might be that it’s also the closest my list gets to post-punk, which I have more time and use for, if only because it includes much more varied textures and moods than straightforward punk. Of course, post-punk eight years before punk is a contradiction in terms, but the grinding, proto-motorik pulse, only emphasized by Cale’s addition of tireless sleighbells and piano to the Stooges’ overdriven guitars, seems to predict the dour doominess of a Joy Division, Magazine, or Bauhaus a decade early. But it wouldn’t be a favorite because of some arcane genre-categorization gamesmanship; so maybe I can get at why I really love it by saying that this is also as close as my list gets to the Velvet Underground, not least because its churning lunkheadedness is much truer to my experience than the arch, distanced ironies of clear inspiration “Venus in Furs.” And that's probably more information about me than you wanted. On a less compromising note, the single edit is in mono, which makes it vastly superior to the stereo version on the album, especially for someone like me with asymmetrical hearing loss.

First encounter: I’ve referenced the Rough Guide to Rock as one of my initial entry points into (one period of) music history. It was actually the spinoff mini-book Rock: 100 Essential CDs that really got me: I spent a week on Napster downloading sample mp3s from each album listed that my early record-store visits hadn’t already netted me, burned them to a series of CDs, and listened through. “I Wanna Be Your Dog” was one of those mp3s, and I was revolted and haunted by it, in great part because I instinctively recognized in it exactly what I love about it now. masculine abasement, industrial grinding, nerve-jangling treble, all build, no release.

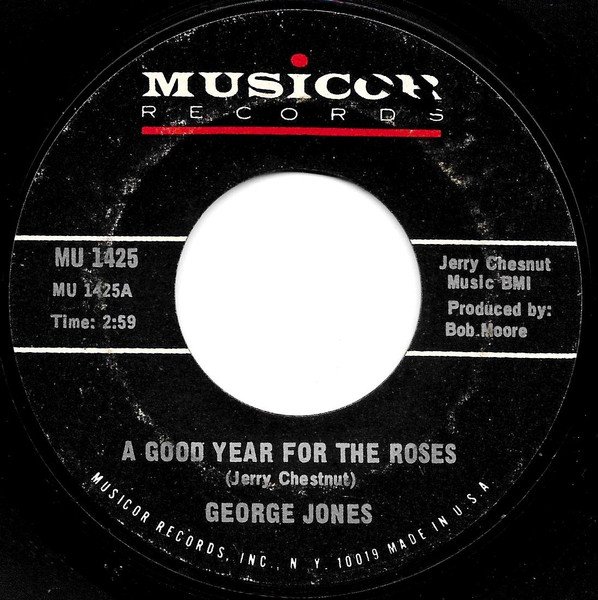

38. George Jones, “A Good Year for the Roses” (1970)

(Chesnut) prod. Bob Moore

Musicor 1425 | #2 C&W

“And a lip print on a half-filled cup of coffee that you poured and didn’t drink”

To my eternal shame, as someone who takes a certain amount of satisfaction in championing American music over European imitations, it took Elvis Costello’s Almost Blue to get me to listen to post-Hank Williams country music with any amount of attention (save for the usual exceptions, one of whom will be coming in at #26, another at #7). It is still Costello’s throaty whine I first hear when I think of the lyrics to “A Good Year for the Roses,” one of his all-time best performances. By comparison, George Jones’ burnished tones on the original are scarcely any more spectacular than his average; but then his average is so much higher that you can’t really see Costello’s from it. Jerry Chesnut’s closely-observed lyric, fitting a world of hurt into a jeweled miniature of inarticulacy, is one of the all-time achievements in country songwriting: a perfectly balanced narrative that tells you exactly why this finicky householder is being left while not stinting on sympathy for his emotional state. If the relatively rinkydink production for Pappy Daily’s small Musicor label (especially compared to the countrypolitan lushness being provided by masters like Owen Bradley at Decca, Chet Atkins at RCA, and Billy Sherrill at Columbia) doesn’t quite live up to the standard being set by Chesnut and Jones, it only makes the songwriting and singing stand out all the more.

First encounter: As the main blurb indicates, I first heard the song covered on 1981’s Almost Blue around 2004, while working the same filing-room job I mentioned under “The Weight.” Not long after, I would have downloaded mp3s of the originals as a reference point (a near-constant practice of mine with covers albums), and although I immediately got the fuss about Possum’s singing, I was also turned off by the starchy backup choir and dinky rhythm section. It took longer and greater saturation in countrypolitan and pre-rock pop orchestration in general to be able to hear them as packing their own sneaky wallop, indications of the narrator’s barren emotional life.

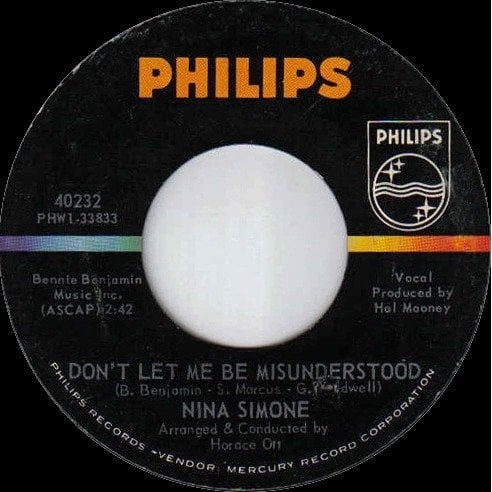

37. Nina Simone, “Don’t Let Me Be Misunderstood” (1964)

(Benjamin/Ott/Marcus) prod. Hal Mooney, arr. Horace Ott

Philips 40232 | did not chart

“Sometimes I find myself alone regretting some little foolish thing, some simple thing that I’ve done”

Speaking of championing American music over European imitations. More than “Time Is on My Side”, “Go Now”, or “Tainted Love” (yes, yes, a different case), the rawest injustice ever done to a black American female performer by an English beat group who covered her rendition of a song, quickly superseding it not only in their home market but in the United States, was Geordie band the Animals covering this in their typical bellowing-cum-organ style. I just relistened to that cover for the first time in ages, after almost two decades of having given primacy to the original, and it’s remarkably weak sauce, a repetitive adolescent moan compared to her powerful, layered performance, with its deep, careful arrangement and molasses-rich textures. It’s both clear why the original wasn’t a hit — her emotionality is both too naked and too pitiless, granting the listener precious little comfort as she pleads for it herself — and a more profound statement than any hit version could have been. It’s an adult-pop record sitting uneasily at the intersection of jazz song, soul, and chanson: commercial radio wouldn’t be ready for that kind of confessional nakedness from a woman until the 1970s, and for that kind of singing maybe ever. Still, that this is my choice for a Nina Simone single, rather than, say, “Mississippi Goddamn”, “Sinnerman”, or “Revolution” may be a kind of political quiescence — but favorites speak to the heart, more to the head or even the conscience. And there are still vast oceans of political meaning in it, because it’s Nina Simone.

First encounter: I undoubtedly absorbed the Animals’ version from oldies radio around the turn of the millennium (I considered it the least of their three big songs in rotation, with the snarling “We Gotta Get Out of This Place” at the top most weeks), and I wouldn’t know about the original for some years, until coming across a snippet of an interview with Eric Burdon where he told a version of his anecdote about being nervous to meet Miss Simone, only for her to cuss him out for stealing her song. I raced to track it down, and I’ve very rarely intentionally listened to any other version since.

Next week: #36-30, featuring some very familiar records but hopefully a curveball or two.