Exist Yesterday: #Let5D0It, Week Four

Still continuing to resend my blurbs on “favorite singles 1954-1976” from my blog.

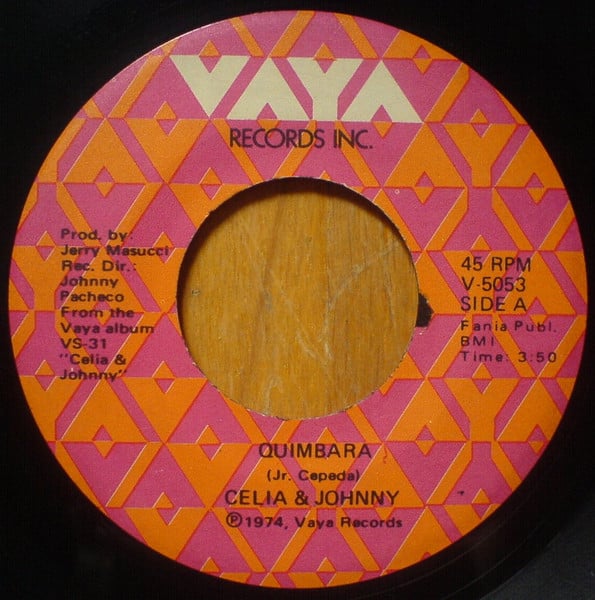

29. Celia & Johnny, “Quimbara” (1974)

(Cepeda) prod. Jerry Masucci

Vaya 5053 | did not chart

“Mi vida es tan solo eso: rumba buena y guaguancó, ee-aa”

It is absurd, given my preoccupations and listening habits over the past decade-plus, that this is the only song in my list in Spanish. I have been a Spanish speaker since childhood, and I have been writing about music in Spanish since 2010 and literature in Spanish since 2017. Unfortunately, my overwhelming interest in Hispanophone culture swelled up just as my overwhelming interest in midcentury music was fading: I put the rest of the twentieth century on the back burner while I tried to build up a vision of global recording from the beginning, and soaked in global music from the 2010s in the interim. So in some ways I’m still playing catch-up to my own ideals, and not having spent much time deeply engaged with Hispanic music from the late 50s, 60s, and early 70s, I’m chary of calling any of it favorite. This is an exception: a whirlwind guaracha sung by Cuban-American Celia Cruz from early in her magisterial phase (which would continue for the rest of her life) backed by the taut, on-a-dime orchestra of Dominican-American Johnny Pacheco, who has as strong a claim as anyone to having developed salsa. “Quimbara” is an Afro-Latin vocable with no precise meaning — linguists posit a derivation from the Kimbundu branch of Bantu spoken in Angola — but what matters is how she uses its syllables with machine-gun precision to evoke the pleasure and freedom of dance and having a good time. Written by Junior Cepeda, a hungry young Puerto Rican who was killed by a jealous lover in New York before getting a chance to meet the diva who recorded his song, it’s become a totemic icon of salsa, one of the bedrock Spanish-language anthems of going out and partying. If you don’t know Latin music and you’re having trouble hearing your way into it, I highly recommend this live rendition from the Zaire 74 music festival, in which the Congolese audience, unfamiliar with Spanish, still can’t help but get swept up in Celia’s exhortations and Pacheco’s hard-rocking rhythms.

First encounter: When I initially committed to participating in this poll, I had to promise myself that I wouldn’t include any new-to-me music, because I know myself and given my head would turn a fun diversion into a full-blown research project packed with amazing music that I’d heard for the first time that month. (I never think I’ve got a complete enough grasp on anything, and have a really hard time existing in the median space between “paying zero attention” and “going way too deep.”) But I started listening to a bunch of stuff I had been meaning to get around to anyways, just in case. And so the first time I consciously heard this song was at my desk a little more than five weeks ago. I’ve heard it at least a dozen times since then, never failing to be moved to dance, to be overwhelmed by the explosive rhythm and the soaring joy of the accompaniment, my breath taken away again and again by the tongue-twister deployment of the title in dizzying rearrangements. And so I think that making this one exception to my rule is ultimately truer than not: I am not done discovering favorites from this era, and I never will be. Everything else on this list I’ve lived with and loved for longer and have grown comfortable in their grooves, but there’s still nothing like that initial jolt of falling in love.

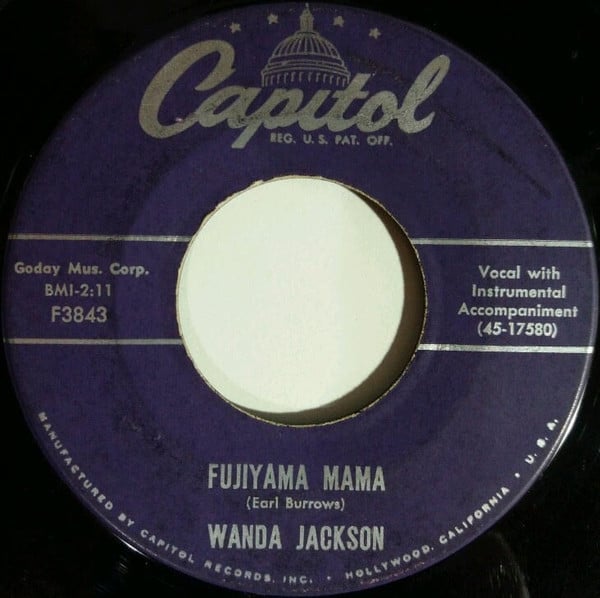

28. Wanda Jackson, “Fujiyama Mama” (1957)

(Burroughs) prod. Ken Nelson

Capitol F3843 | #1 JP

“I drink a quart of sake, smoke dynamite”

No overview of this period in American music would be complete without at least one stunning example of utter tastelessness. The safe, uncontroversial way to do this is to include some garage-rock standard or other, maybe “Louie, Louie,” “Surfin’ Bird,” or “Psycho” — while the hipster elite version might be to include the Legendary Stardust Cowboy, the Fugs, or the Shaggs. My choice, dictated first by what I actually like and secondarily by the story that goes with it, is an unhinged rockabilly stomp invoking the nuclear devastation of Hiroshima and Nagasaki only twelve years after the fact, something so foul-minded that only the fact that it went to #1 in Japan and inspired covers there that were understood as rallying cries for female self-determination lets it off a, if not the, hook. Wanda Jackson is often considered little more than a footnote in the male-dominated landscape of early rock & roll, especially since she rarely troubled the U.S. pop charts, but her full-throated assault on uptempo numbers like this one, switching between a gravely yell and a hiccuping coo, is a direct predecessor to riot grrrl aesthetics, and is one of the things that made me fall in love with rockabilly past the initial everybody-knows-’em hits (“Jailhouse Rock,” “Blue Suede Shoes,” “Summertime Blues,” “Be-Bop-A-Lula,” etc.) in the first place. It’s not the original version of “Fujiyama Mama” — written by the guy who wrote the equally hyperbolic and potentially blasphemous “Great Balls of Fire,” it was first sung by an R&B chanteuse, then by a mainstream pop singer, both in 1955, without doing any business whatever — but it’s been most strongly identified with Wanda ever since her stripped-down, grab-you-by-the-lapels arrangement threw out the novelty elements of those records and turned it into a pure snarl of id.

First encounter: I spent so much time between 2000 and 2006 clicking around the Related Artists field on Allmusic.com that that wouldn’t be a bad title for a memoir of my musical obsessions. In this case, I believe I got onto Wanda Jackson around 2001 because she kept showing up there when I was looking at acts like Eddie Cochran and Gene Vincent, trying to dig deeper into the 1950s and believing cussedly that there had to be important women in every genre and subgenre I found thrilling. Wanda Jackson was more than thrilling and became immediately central to my sense of 50s rock & roll — her 1960 cover of “Riot in Cell Block #9” almost blows the Robins’ original out of the water, but it was only an album track — and although I have always primly deprecated this song’s vulgarity, revisiting the catalog for this exercise got me reluctantly on board. This is the only genuinely rockabilly song on the list, because after that, where can you go?

27. Aretha Franklin, “Think” (1968)

(Franklin/White) prod. Jerry Wexler

Atlantic 2518 | #7 US, #26 UK

“But it don't take too much IQ to see what you're doing to me”

Wound tight as a spring, a burst of vituperation and self-assurance cleaving a whole ten seconds off the running time of its obvious ancestor, the previous year’s “Respect,” which sounds shaggy and pokey by comparison. Don’t get me wrong, “Respect” is indisputably a more monumental record, possibly even a better record, however objectively such things can be measured. But after years of oldies radio, girl-power sloganeering, and sheer cultural exhaustion, I don’t, or can’t, like it as much as “Think.” (And on a goofier level, I can only feel good about including one song in this list that uses the Laugh-In catchphrase, no matter how righteously reappropriated.) I don’t imagine I need to make a case for including Aretha Franklin, one of the four or five most important singers of the twentieth century, on my list. Although I will note that she was not on the first revision: but after relistening to Koko Taylor’s “Wang Dang Doodle” I realized that she wasn’t quite the representative of female black sixties forthrightness I wanted, and so Aretha moved down from the Hall-of-Fame rafters where I had placed the immortals who wouldn’t need my help crossing any finish lines. “Think” was the obvious choice for her representative single (I considered “I Never Loved a Man (The Way I Love You),” “(You Make Me Feel Like) A Natural Woman,” and “Chain of Fools,” but only briefly), and although it took me a while before I found the streaming version that matched the song as it existed in my memory, the crisp punch and holler of the record — one of the few Aretha herself ever deigned to pen — felt exactly right among all the other 49 I was accumulating.

First encounter: An early cautionary tale of mp3 filesharing: in 2000, trying to get my initial grasp of the twentieth century’s musical highlights, I downloaded Franklin’s 1980 re-recording for the Blues Brothers soundtrack, unaware that it was not the 1968 original. I loved it: the gospel arrangement, the disco strut, the unspeakable sass on “if you keep doin’ things I don’t,” the Broadway finish. At some point, of course, I discovered my mistake, and when I submitted meekly to the 1968 Atlantic recording I found it thin, muffled and rushed, over almost before it began. Of course, I was listening to the stereo Aretha Now! track, not the mono single, which is still fast but not inhumanly so, and doesn’t sound shyly quieter than whatever preceded it in a shuffled mix. But I am grateful to that slower re-recording, because it taught me the lyrics and the thrust of the song, which as I listened and relistened to the original became more and more essential to me, until that building, lifting “freedom, yeah freedom” refrain rang far more truly at the intersection of Civil Rights and Women’s Lib than “Respect” ever did.

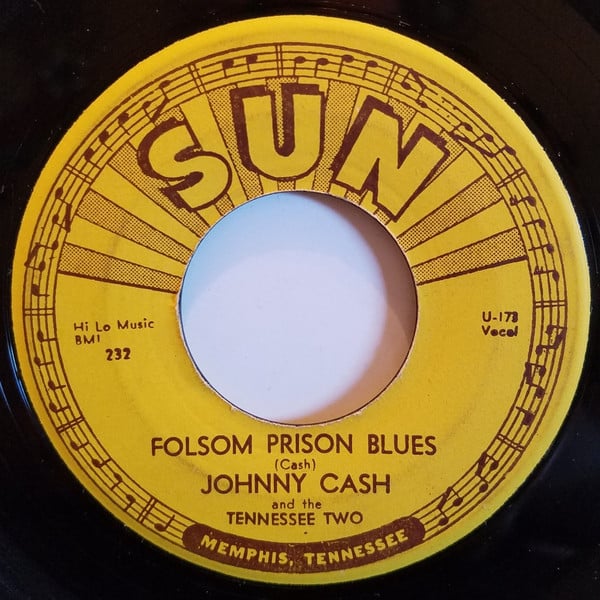

26. Johnny Cash & the Tennessee Two, “Folsom Prison Blues” (1955)

(Cash) prod. Sam Phillips

Sun 232 | #4 C&W

“Well I know I had it coming, I know I can’t be free”

Wait a minute: if “Respect” has been bleached nearly free of meaning by endless repetition, how has this not been? Good question, and I don’t know that I have a non-equivocating answer. It certainly isn’t something like Johnny Cash’s granite voice being more durable than Aretha fucking Franklin’s; ultimately the fault lies with me rather than the records. I wasn’t at all sure I’d include this song on the list, and in fact “Get Rhythm” was on an early draft until I relistened to the racially condescending verses and scratched it; but revisiting my personal Cash highlights left me convinced that it was either “Folsom Prison Blues” or “Ring of Fire” and I was still inexcusably light on 50s songs. (And if I’m going to highlight mariachi horns I’d just as soon have the real thing.) It does at least give me an excuse to include something from Sun Records, as totemic for me as for any other soft touch for the mythographical side of rock history, and of the big four Sun artists, I’ll take Cash any day over Presley (the poor sap), Lewis (the horror show), or Perkins (nice guy finishing last). I used to hear the line “those people keep a-movin’ and that’s what tortures me” as a potential glimpse into some awful inhuman psychopathy, aided by Cash’s bone-dry gravitas, but a decade of social-media exposure to the most prevalent current forms of inhuman psychopathy make it seem entirely normal instead, a mere portrait of a prisoner who undoubtedly did the crime but, because he’s still human, simply isn’t equipped to do the time. It’s far from being an anti-carceral anthem, but still: humanizing the people that society would rather not consider at all used to be a major function of country music, all the way back to the folk ballads and blues songs that formed its basis. Today’s country radio is all too often by and for the rich folks in the fancy dining car.

First encounter: Unlikely as it may seem, I was a full adult before I ever heard Johnny Cash. “Walk the Line” was among the first mp3s I downloaded from lists of the best songs of the 20th century; and At Folsom Prison was among the first few dozen CDs I ever bought from lists of the best albums. American IV: The Man Comes Around (2002) made me a fan for life, and a few years later I would bought a compilation of his Sun sides, which I think is where I first heard the original “Folsom Prison Blues,” without the faked cheering for the “shot a man in Reno” line. The spare, dry-as-dust voice-guitar-drums arrangement still feels both primal and modern, an electric primitivism consonant with, if not equivalent to, rock & roll.

25. William Bell, “You Don’t Miss Your Water” (1961)

(Bell) prod. William Bell

Stax 116 | #95 US

“In the beginning, you really loved me”

A lot of these entries can be understood as stand-ins: one record to represent a wide swathe of others that there wasn’t room for on a list of merely 50. In that sense, this record can be seen as standing in for the transition between R&B and soul, to the degree that that is a distinction with a difference. The simple, almost barebones structure, stately as a hymn and plainspoken as a folk song, is deceptive: Bell’s performance is as nuanced and carefully tailored to the lyrics as a jazz singer’s, but in an entirely different idiom, foregrounding emotion and dynamics rather than phrasing and pitch. Aside from New Orleans (always its own beast), the South was underrepresented in the national R&B scene of 1961, which was dominated by northern-bred crooners, midwestern vocal groups, and early versions of the Detroit sound. This song, written and recorded by a jobbing musician homesick for Memphis, was in a very real sense a 1960s version of “the South got something to say” — and although it failed to make the R&B chart at all and only scraped the bottom rungs of the Hot 100, it rapidly became a classic within the Southern R&B circuit where voices like Otis Redding’s, Solomon Burke’s, and Mavis Staples’ were still regional secrets and not yet national treasures. Within a year or two, it would already start to sound old-fashioned, as the studio musicians at Stax in Memphis and FAME in Muscle Shoals developed harder-hitting sounds and hungrier young singers explored the limits of their vocal chords.

First encounter: I’m pretty sure I first heard it via the cover on the Byrds’ Sweetheart of the Rodeo, during a period of fascination with Gram Parsons circa 2004. I quickly tracked down the original, and it was paired for many years with James Carr’s 1967 “The Dark end of the Street” in my mind as twin slow-burn Sixties soul classics that were hugely underrated compared to the punchy uptempo numbers by the likes of Wilson Pickett, Eddie Floyd, and Arthur Conley that were my initial introduction to the classic Southern soul milieu. In 2008, I called it one of the 10 best songs of the 1960s that didn’t get regular oldies radio play; in 2024 it took three or four revisions of this list before I remembered to add it. I believe the spot was initially held by Ray Charles, if you were curious about just how much more classicist it could have been.

24. Elza Soares com Oswaldo Borba & Sua Orchestra, “Se acaso você chegasse” (1960)

(Rodrigues/Martins) dir. Ismael Corrêa

Odeon 1042 | #12 BR (year-end)

“E assim nós vamos vivendo de amor”

For a while a few years back I revolved a half-thought-through schema in which a handful of debut (or at least introductory) singles by black women in 1960 could be taken as a ground zero for musical modernity. Alongside Aretha Franklin’s “Won’t Be Long,” Miriam Makeba’s “Click Song,” La Lupe’s “Fiebre,” and a record nestled on my list below at #21, Elza Soares’ “Se Acaso” seemed to fit in as an unexpectedly explosive and undeniably black takeover of a music that had been gentrified and made cozy for the white bourgeois: supper-club jazz in Aretha’s case, kwela in Miriam’s, bolero in Lupe’s, girl-group in the redacted artist’s, and samba-canção in Elza’s. But the more I listen, the less accurate definitive breaks and instant newness look as models for musical history: and in fact the startling modernism of this record could be said to date way back to 1926, when Louis Armstrong recorded “Heebie Jeebies” largely in scat. Elza Soares always claimed her performance style was developed originally, in ignorance of any North American precedent, but “Mack the Knife”, which Armstrong had made a global smash in 1955, was the B-side to this record. In any case, within the borders of samba, her growling, wordless vocalizing in bursts of spiraling melodic improvisation was understood as not just virtuosic but shocking, a jolt to a conventionalized music scene and almost antagonistic to the soft-spoken, white-coded bossa nova innovations then being hailed as Brazilian music’s ticket to international recognition and respectability. Elza’s second album was called A Bossa Negra (the black beat), and she would continue to represent unapologetic blackness and difference within Brazilian music, even having her house firebombed by the military dictatorship in 1970 as a warning against taking pride in one’s favela origins. Even this record, airy and jazzy as it may seem decades later, was daring — written by Lupicínio Rodrigues in 1938 in order to mollify a friend whose girl he had stolen, it’s a rascally song of betrayal celebrating the singer’s domestic routine, including conjugal, with another man’s wife. By 1960 it was a standard, but Elza didn’t change any genders, singing about stealing your woman herself. Her voice burbles off into scat on getting to the lines about making love with her, but no Brazilian would have missed the implication. It’s modernist after all.

First encounter: One of the most recent to have joined the ranks of my favorites, this record’s place in my affections dates only to 2017, when I took a couple days to research and throw together a list of great albums by women before 1964, in cheeky response to an NPR list of great albums by women since then. The name Elza Soares had been bubbling away at the edges of my appreciation for Brazilian music for some years, but it was her 2015 comeback album Mulher do Fim do Mundo and more importantly her stunning 2017 video for the title track that jolted me into awed awareness of her long legacy of radicalism within Brazil’s deeply racially stratified music scene.

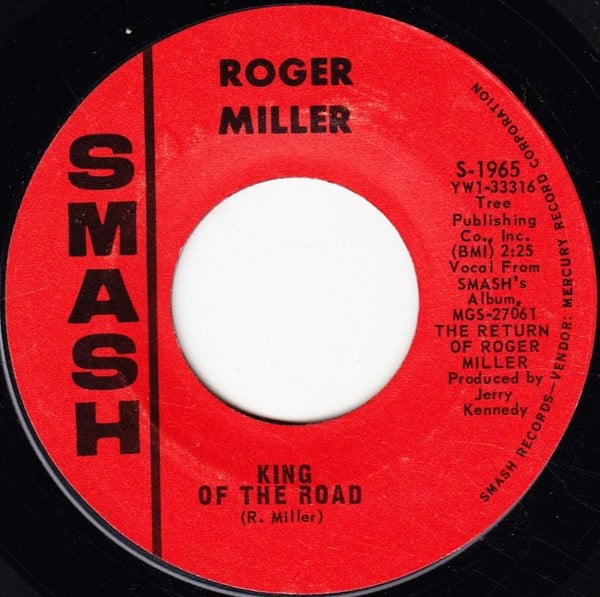

23. Roger Miller, “King of the Road” (1965)

(Miller) prod. Jerry Kennedy

Smash 1965 | #1 C&W, #1 EL, #4 US, #1 UK

“Every lock that ain’t locked when no one’s around”

The optics of a successful country songwriter having a huge hit with a cutesy, idealized ode to houselessness and vagrancy make me tired just thinking about the discourse that would be generated by a twenty-first century equivalent. But part of the point of spending time with voices from the past is that they really are from another country: homelessness in 1965 was not homelessness in 2024 — and it also wasn’t homelessness in 1928, when Harry McClintock, who had lived an itinerant life himself, recorded foundational tramp songs like “The Big Rock Candy Mountains” and “Hallelujah I’m a Bum,” songs quickly adopted by the burgeoning left-populist movement that produced the likes of Woody Guthrie. Roger Miller — who came himself from subsistence-farming origins in post-Dust Bowl Oklahoma — was consciously participating in a quasi-commercial folk tradition of songs celebrating outcasts and dropouts from society, voluntary or no; and although the pristine production polish of a song that could top the mid-60s easy listening chart might seem to work against any folk “authenticity,” Miller isn’t trying to be authentic either. On closer listen, the song can be read as a Randy Newmanesque portrait of a guy who’s fooling himself — “I don’t pay no union dues,” he boasts near the historical height of union membership in the country — in ways that the generous midcentury economy allows him to. “Rooms to let fifty cents,” ffs (yes, I know what inflation is). But ultimately the sly charm of Miller’s singing and deceptively simple songwriting are their own reward, pop perfection no matter how it’s interpreted politically.

First encounter: Like many in my generation, I first knew Roger Miller from the soundtrack to Disney’s 1973 Robin Hood, and if “Not in Nottingham” had been an A-side I might have been tempted to include it as among my first-ever favorite songs. I believe I knew “King of the Road” by high school at the latest, but where I would have picked it up is a mystery: I seriously doubt it got airplay on Guatemalan English-language radio 1992-1996, and there were no secular records in the house growing up. In any case, it would have been among the first hundred mp3s I ever downloaded, and has been a relatively constant presence in my life since then.

Next week: #22-16, in which I start to wax a little more prolix on some of these records. You have been warned.