Exist Yesterday: #Let5D0It, Week Five

Still continuing to resend my blurbs on “favorite singles 1954-1976” from my blog.

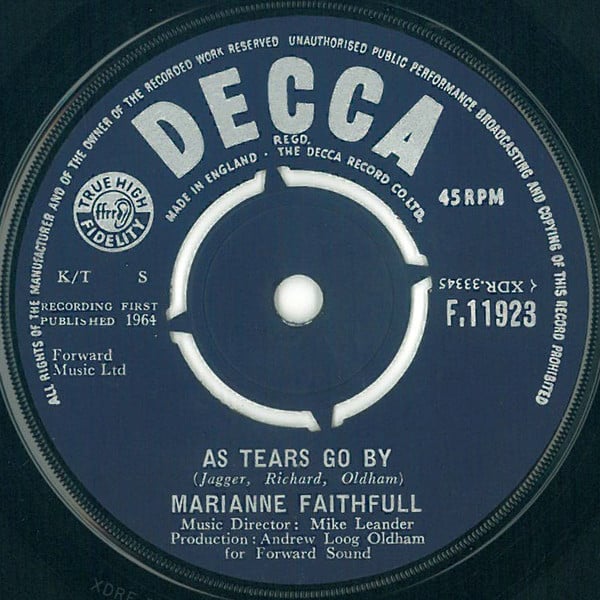

22. Marianne Faithfull, “As Tears Go By” (1964)

(Jagger/Richards/Oldham) prod. Andrew Loog Oldham

Decca F-11923 | #22 US, #9 UK

“Smiling faces I can see, but not for me”

“No Elvis, Beatles or the Rolling Stones” — I may have an ambivalent relationship to punk, but that snarl-moaned Joe Strummer lyric from a 1977 B-side was one of my first principles for this list. Not because I dislike Elvis, Beatles or the Rolling Stones: I like them a lot. But they’re also culturally monolithic in a way that has kept me appreciating them mostly from a distance, rather than in the personal way that favorites require. The Stones came the closest, but my two favorite Stones albums, Between the Buttons (US edition) and Exile on Main St., don’t excerpt well. The Exile energy I love is represented further down on this list anyway; but the Buttons energy begins here. I have an enormous soft spot for 60s chamber-pop: the Left Banke or late-period Zombies would have made a lot of versions of this list if I wasn’t shooting for more diversity than that. But I have an even bigger soft spot for Marianne Faithfull — and sure, most of that is because of her post-junkie material, once she grew into the persona of the raspy-voiced grand dame of twentieth-century English chanson. But even here, in her nervous seventeen-year-old alto, you can hear an echo of that posh survivor. The story goes that Jagger and Richards were locked into a room and forced to write the song by their manager primarily for the publishing income, since their covers of US rhythm & blues songs were making them less rich than originals would, and Richards would be openly contemptuous of it — “money for old rope,” he called it — but Jagger’s elliptical lyrics about nostalgia, faded glories, and envy of youth are more compelling, especially in a woman’s voice, than nine-tenths of his pseudo-provocative rock star posturing. (He was always a middle-class art student, not a bluesman.) The record’s oboe-and-strings arrangement, giving it a strangely timeless quality right in the heart of Swinging London’s beat obsession, predates the Beatles’ experiments with Baroque instrumentation like “Yesterday” and “In My Life” by over a year, and helps to sell the illusion of the teenaged Faithfull’s premature decrepitude. You could imagine Édith Piaf singing the song; but Faithfull’s lack of theatrics makes it even cooler.

First encounter: There was a period in the early 2000s when my most frequent sources for musical education were a couple of deeply rockist obsessives with their own websites who reviewed hundreds of records and gave them idiosyncratic scores; they both wrote condescendingly about Marianne Faithfull’s version of “As Tears Go By” in reference to the Stones’ own later version, so of course I had to hear it. And of course I loved it, not least because it sounded so different from the Stones: a broad textural and sonic palette has always been one of my biggest priorities as a music fan, which has sometimes made getting into narrowly-defined scenes a chore and eventually made me prioritize singles, mixes and wide-ranging playlists over albums, especially cohesive ones. Thanks, M. Prindle and G. Starostin, for setting a standard I have done my best to distance myself from ever since.

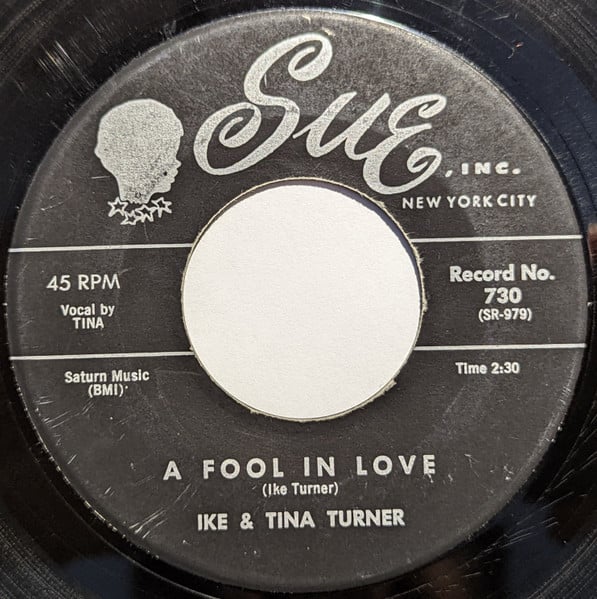

21. Ike & Tina Turner, “A Fool in Love” (1960)

(Turner) prod. Ike Turner

Sue 730 | #2 R&B, #27 US

“You can’t understand how he treats you like he do when he’s such a good man”

It’s remarkable that it took until the 1986 publication of I, Tina for Ike Turner’s controlling, abusive, and violent treatment of the woman he made famous and who in turn made him rich to come to light. He had already told us everything with the lyrics this record, the debut single under the Ike & Tina name as well as Tina’s debut under that name (she had sung backup as Little Ann on a 1958 record). The Ikettes chant the circular, minimizing, self-abasing messages that abuse victims internalize while Tina moans and shrieks in shattering pain — or is it rage? or is it ecstasy? or is there even a difference? — blowing out the top of the dynamic range on Ike’s legendarily cheap recording equipment. Even during the verses when she speaks for herself, she vacillates between brutal honesty and sugary platitudes: “He’s got my nose open and that’s no lie, but ah, I’m gonna keep him satisfied.” Like, what the fuck? There has rarely been a clearer, more psychologically penetrating portrait of abuse and the things people tell themselves (abetted by social pressure) to make it okay in twentieth-century literature, let alone pop; and it flew under the radar for decades. Even after I, Tina, someone as adept at reading meaning into songs as Dave Marsh considered this a simplistic love ditty only made ironic in retrospect due to the “he’s such a good man” line; but then of course it’s only harrowing if you listen to it that way. Purely as pop, it functions amazingly, a sharper-elbowed, rougher-edged girl group sound than the stately hymnody of the Chantels or the teenage bathos of the Shirelles — Tina Turner was only twenty when she sang this, but she sounds electrically adult, with decades of pain under her belt; although she recorded so much more music that I adore with Ike up until she finally escaped him in 1976, none of their other singles (especially not the one with the other legendary 60s abuser) are as compelling as this opening burst of adrenaline announcing Tina goddamn Turner to the world.

First encounter: I remember specifically the 2003 (or so) trip to the record store when I bought the 1991 comp Proud Mary: The Best of Ike & Tina Turner, because it was also the trip where I bought My Bloody Valentine’s Loveless and I could feel the bemusement of the friend I was with, whose favorite music was jam bands, at my late-blooming eclecticism. I felt slightly guilty about the Ike & Tina purchase because even then I was anxious to not appear to be supporting abusers (like nearly all of my purchases in those days, it was a used CD), so when I listened to it I was primed to read horror into the subtext of the records: what I didn’t expect was to find it in the text itself.

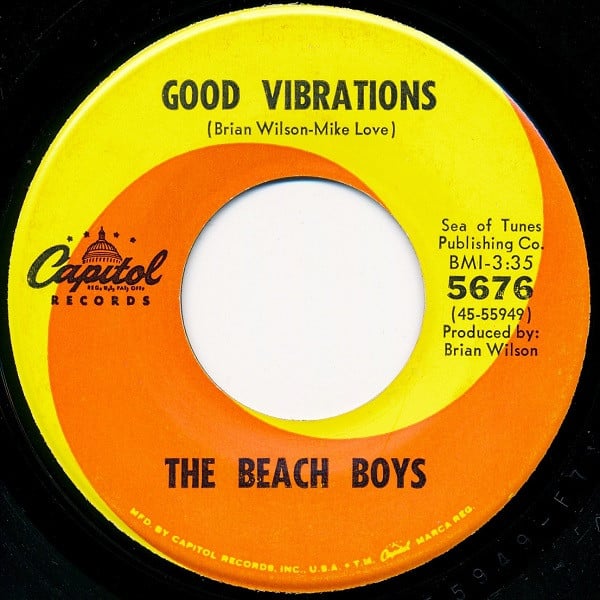

20. The Beach Boys, “Good Vibrations” (1966)

(Wilson/Love) prod. Brian Wilson

Capitol 5676 | #1 US, #1 UK

“Softly smile, I know she must be kind”

In the first week of this poll project, Tom Ewing posted a list to Bluesky of the 50 songs eligible for it from Acclaimed Music’s most-lauded songs list; I was abashed to realize that I had as many as seven (six after swapping out “What’d I Say” at #25) songs in common with it. This is AM’s second highest-scoring single, behind “Like a Rolling Stone” (“A Day in the Life” is ruled only an album track). I made my peace with Dylan back at #41, and this is me making my peace with the Beach Boys. “Good Vibrations” was my first favorite Beach Boys song, as detailed below, but the more I engaged with music-crit discourse the more I came to consider it jejune and obvious, and cycled through more and more private and obscurantist tracks over the course of a decade — “In My Room,” “Don’t Worry Baby,” “God Only Knows,” “I Just Wasn’t Made for These Times,” “Heroes and Villains,” “Surf’s Up,” “Farmer’s Daughter,” “Dance Dance Dance” (but only when paired with Joy Division’s “Transmission”), “Guess I’m Dumb,” “Cool, Cool Water,” “Sail On, Sailor” — until a month ago, looking at a blank ballot sheet for this poll and asking myself what Beach Boys song I should pick and only hesitating a little before I put down “Good Vibrations.” Listening to it over and over in context of the fuller list, I’m more and more confident I made the right choice. Yeah, it’s corny and airheaded, featuring one of Mike Love’s most goobery lyrics in the chorus (which is saying something). It’s also gorgeous, a deep mesmerizing mix of sounds and gear changes and soaring harmonies. Even the tape wrinkle on the first line of the second verse, in which the Wilsons’ voices are suddenly garbled while singing “close my eyes” for a moment — which for years I thought was an artifact of an improperly downloaded mp3, and tried over and over again to find a clean copy until I finally bought a pristine copy of Sounds of Summer: The Very Best of the Beach Boys and realized it was always there — contributes to the slightly out-of-focus kaleidoscope that is the whirling, restless, expansive montage of “Good Vibrations.” No more intelligent lyric could have bettered the song: a plaintive Tony Asher or a whimsical Van Dyke Parks would have buried it commercially, leaving it another sunken treasure in the graveyard of Wilsoniana; but instead it was an enormous Technicolor hit, a sun-kissed version of the kinds of vaulting ambitions more often represented in rock by slabs of self-indulgence like “Stairway to Heaven,” “Bohemian Rhapsody,” or “November Rain.” But sawing cellos and a wailing electro-theremin while Hal Blaine’s drums crash like waves in the distance manage to be cozy even while evoking grandeur: it’s the pocket part of “pocket symphony” that makes it work.

First encounter: In 1999 I downloaded Napster. Not long afterward, I burned a CD inspired by my earliest canon-plundering investigations called something like The 21 Best Rock Songs Ever, which began with “(We’re Gonna) Rock Around the Clock)” and “Jailhouse Rock” and ended with “Where the Streets Have No Name” and “Smells Like Teen Spirit.” The centerpiece was “Good Vibrations,” the exact midpoint of the mix, and in the comics-inspired art I drew for the jewel case cover, with one small panel representing each song, it was the only one in full color. Physically, I was twenty years old; emotionally, and in terms of average level of pop-culture awareness at the time, I was probably somewhere closer to eleven. A lot of my musical taste, or at least what I write about my taste, is driven by a kind of repulsion towards earlier versions of myself who knew far less, thought much more uncritically, glibly parroted conventional wisdom, and were in every respect deeply uncool — in this case, though, I can feel nothing but exasperated fondness toward that dirt-ignorant dork who, no matter the vastness of his blind spots, could still use his ears.

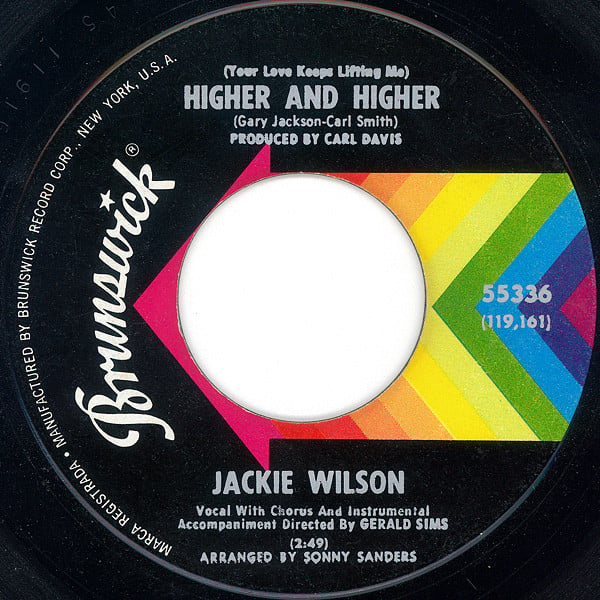

19. Jackie Wilson, “(Your Love Keeps Lifting Me) Higher and Higher” (1967)

(Jackson/Smith) prod. Carl Davis

Brunswick 55336 | #1 R&B, #6 US, #11 UK

“Disappointment was my closest friend”

This spot started out belonging to the Four Tops, influenced in no small part by Chris O’Leary’s current meta-massive project at 64 Quartets; but the more I thought about it the more I had to admit to myself that my Four Tops appreciation has long been at best secondhand — and anyway there were already two Motown songs in the top 10, and I needed to spread the love around a little more than that. Another name came to mind, not related to the Four Tops, but frequently close to my heart, and it would give me a chance to exercise a kind of writing I don’t often indulge in; but again, the more I thought about it the less I wanted to spend an entry vigorously disapproving of a senior citizen while celebrating his youthful appropriations — so instead I settled on the artist who would have been at the center of the single I would have chosen anyway, and I get to nod towards both the Four Tops and Van Morrison at once. One of the best Motown imitations of all time — but is it really an imitation, when James Jamerson, Richard “Pistol” Allen, Robert White, Johnny Griffith, Mike Terry, and two of the Andantes came down to Chicago for the session, as producer Carl Davis claimed? “(Your Love Keeps Lifting Me) Higher and Higher” floats in ways that Levi Stubbs’ aching baritone could not, Jackie Wilson’s gleeful falsetto pushing towards the stratosphere as though in awareness that the song is liberating him not just from lovelorn despondency but from being shackled to a reputation as a has-been coasting on Fifties oldies like “Reet Petite” and “Lonely Teardrops.” Both of which were absolutely in contention for this spot — Wilson’s energetic brio was always ahead of its time — but I’m a sucker for triumphalist second acts.

First encounter: I feel like I must have heard it on oldies radio, but what I really remember is listening to Rhino’s Incredible Soul Collection comp in that car dealership file room in 2003 and having to physically restrain myself from dancing in case someone came in. Like a lot of the widely and justly beloved music on that compilation, I’ve had periods of taking it for granted over the years, but all I need to do is listen again and it’s a shot of pure ecstatic dopamine, one of the most perfectly arranged, sequenced, and performed pieces of aural bliss ever waxed.

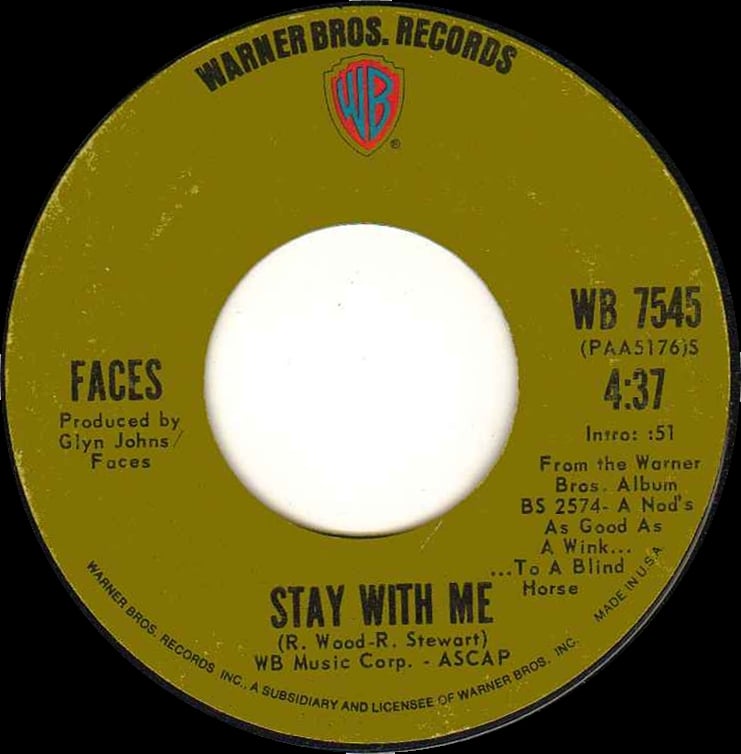

18. Faces, “Stay with Me” (1971)

(Stewart/Wood) prod. Glyn Johns

Warner Bros. 7545 | #17 US, #6 UK

“You won’t need too much persuadin’, I don't mean to sound degradin’”

And now my rock chickens come home to roost. In discussing Suzi Quatro at #45, I wrote: “Women getting rowdy and yelling with joyous swagger can still feel fresh and necessary when men doing the exact same thing often feels ugly and regressive. (But again, more later.)” This is the later. And I will be the first to say that this is an ugly, regressive song, a mean-spirited, misogynistic, slut-shaming, cruel song that represents everything I wish not to be in my personal relations but fear I am anyway. And yet. My heart still lifts when I hear Ron Wood’s scuzzy, fuzzed-out guitar in the left channel peeling out that drag-race riff — by which I mean it’s descended from dragster-themed rockabilly like “Hot Rod Lincoln,” although there’s also a sense in which this is a song deeply about the over-the-top performance of gender. The Faces, more than any other band of their era, milieu, and rockstar fame, were all about mateyness, which is the best feeling in the world when you’re part of the gang of mates, and sickeningly vile when you’re their target, in either the lascivious or bullying (or frequently both) sense. The music staggers, pleasantly drunk, Ian MacLagen’s Rhodes piano rolling like a barroom in a high wind, and Rod Stewart leers, slurs, negs, jokes, threatens, and cajoles in his most ingratiating rasp, whooping like a cock crowing as the band pounds into lairy violence around him. The double-time section is pure hooliganism — Glyn Johns doesn’t do anything as crass as splice in the sound of bottles breaking, but he doesn’t need to — the band coming to woozy stop after woozy stop in order to show of two-second solos by each player, a crisp Stax-inspired sense of instrumental indulgence at beery, loutish odds with the self-serious rock-god soloing then unfurling across FM album-oriented-rock formats. There isn’t a straight line, smooth surface, or square corner anywhere on the record: even Ronnie Lane’s bass crackles with overcharged energy and Kenny Jones’ drums rattle precariously, only barely finding the pocket every time. There are better, by which I mean more morally upright, or at least less morally compromised, Seventies rock songs; I love quite a few of them. The Faces even made some of them. But what keeps me coming back to “Stay With Me” is the fact that despite its ugliness and squalor and toxic masculinity — in fact, because of all these qualities — it is, at its core, honest. There’s no attempt to paint themselves in the most flattering light, no attempt to wheedle the girl, either in the song or dancing in the crowd or listening to the radio, that there’s any sentimental surrender in their pitch. (Sentiment is reserved for the Ronnie Lane songs.) This, I feel it salutary to remember always, is what rock is. Not the sum total, perhaps, of what it is, but enough of it to be inextricable: prolonged adolescence, men behaving badly, indulging every appetite, making a glorious racket, one rule for thee another for me, and on again to the next venue, the next conquest, the next hangover — shorn clean of any of the spiritual, political, or vanguardist pretensions the Sixties had larded onto the basic guttural yawp of desire and cocksureness that was rock & roll, the music that coalesced in juke joints and dive bars by men — primarily, yes, black men — to express earthy desires in opposition to the sanctified shouting and strumming and clapping where the rhythms and sounds they played had originated. The Devil’s music, in short. The greatest trick he pulls may change with every generation, but there’s still a very real sense in which I cue up the Faces and cock a smile and decide for the space of a song that all right, then, I’ll go to hell.

First encounter: I came late to an appreciation of the Faces, because my first encounter with Rod Stewart was in 90s aging-crooner mode and I assumed he had always been, in the invaluable British phrasing, naff. I had an mp3 of “Ooh La La,” from the Rushmore soundtrack, kicking around my hard drives from fairly early on, and I loved it, but I was still wary because all the critics I read said that they weren’t up to the standard of the Rolling Stones, Led Zeppelin, or the Who. It wasn’t until I had learned enough to put soul and r&b nearer than rock to the heart of midcentury music that I could hear Stewart’s throaty Sam Cooke imitation as being more intimately central to my growing picture of early 70s music, growing out of the tangled garden of rock, soul, country, and blues, than Jagger’s prissy yarl, Plant’s banshee wail, or Daltrey’s bullhorn bellow. At some point in 2003 or 2004,“Stay With Me” came on classic rock radio and electrified me; I felt winded by the time it was over. I went out and bought the four Faces albums as well as Rod Stewart’s first four solo albums, on which they largely played. I soaked in their music for what felt like years. I listened so hard that I made myself cry to dozens of their songs. They are still, if I have one, my favorite band. I hadn’t listened to them for a solid decade before I compiled this list. I will probably spend the next several hours doing so now.

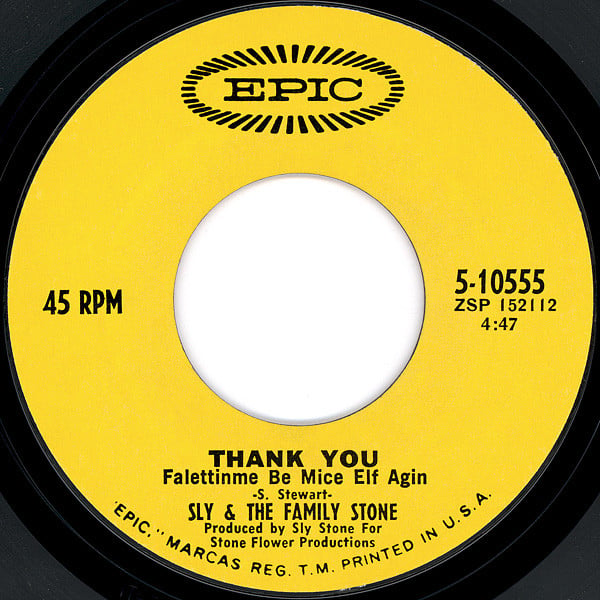

17. Sly & the Family Stone, “Thank You (Falettinme Be Mice Elf Agin)” (1969)

(Stewart) prod. Sly Stone

Epic 5-10555 | #1 R&B, #1 US

“Looking at the devil grinning at a gun”

There’s a certain kind of Sixties rock cheerleader for whom the center of all that was good and holy in the second half of the decade was located in San Francisco. By that they usually mean shaggy, tantric acid rockers like Jefferson Airplane, the Grateful Dead, Big Brother and the Holding Company, Moby Grape, Santana, and lesser lights — but the two Bay Area bands that had nothing to do with the incestuous, navel-gazing Haight-Ashbury scene and took a less noodly, more r&b-based approach to adventurous, political pop aimed just as much at singles and radio play as the album market are the ones that have worn the best in the nearly sixty years since: Creedence Clearwater Revival and Sly & the Family Stone. Creedence didn’t make my list, because I only have so much patience for roots rock these days (on a different week, they could have subbed in for the spot taken by the Band), but Sly Stone and his psychedelic soul revue are indispensable to my understanding of and affection for the flower power era, tenuous and misguided as it was. Their early hits can be a little hard to take, not so much because their starry-eyed Up With People sloganeering is cheesy in its own right (far less because it’s not cut by wickedly funky attitude), but because it’s been recycled so frequently by pseudo-colorblind mealymouthed centrists that it’s been processed into meaningless pabulum. So of course the darker turn as the Sixties dream curdles into violence and paranoia — if not the actual harsh vibes of their Seventies — is where I choose to take up residence within the rambling Family manor. The shoutalong chorus of “Thank You,” an expression of gratitude, is still anchored in positivity, but Larry Graham’s popping bass struts more toughly and snakily than any of their (or anyone else’s) sunshiney love-ins had ever done before, inventing giant swathes of 70s funk in the process; and the verses, tautly group-chanted rather than traded joyously and raggedly off as in previous form, circle tightly around spare, bleakening imagery rather than pithy apothegms. Except for the third verse, a reprise of previous single titles — and, due to “Thank You”’s position as the final song on the 1970 Greatest Hits album, an ominous dividing line between past and future. Even the spelling of the parenthetical complicates the positivity, transforming the notion of self-actualization within a supportive social context into a private fantasy, a joke it’s possible to not be in on.

First encounter: The only job I’ve ever been fired from, instead of quitting, was the job I mentioned in #34 working for an auto insurance adjuster. The reason I was fired was that I wasn’t doing enough work, but spending my time researching music on company time. (The guy who fired me, who wasn’t the boss, who took the day off so he wouldn’t have to look me in the eye, expressed bafflement at my visiting hundreds of Allmusic.com pages in an hour; I didn’t think it would help to tell him that it was because I had only been grabbing a single piece of information from each.) I stumbled out to my car in the hot Phoenix midday and put in a CD I had recently picked up, hoping that the uplifting positivity of Sly & the Family Stone’s Greatest Hits would soothe my furious, self-recriminating, despairing, guiltily relieved nerves, and drove. I let it play over and over again, heading north out of the city at speeds my junky little Toyota could barely handle, while Sly, Freddie, Rose, Cynthia, Jerry, Larry, Greg, and Little Sister shouted, wailed, hummed, and laid down funky riff after funky riff. I was more than an hour on I-17 before I finally felt calm enough to exit at Black Canyon City and turn around and head back toward home. To this day I never hear the fadeout on “Thank You (Falettinme Be Mice Elf Agin)” without expecting to hear the stirring blast that opens “I Want to Take You Higher” next.

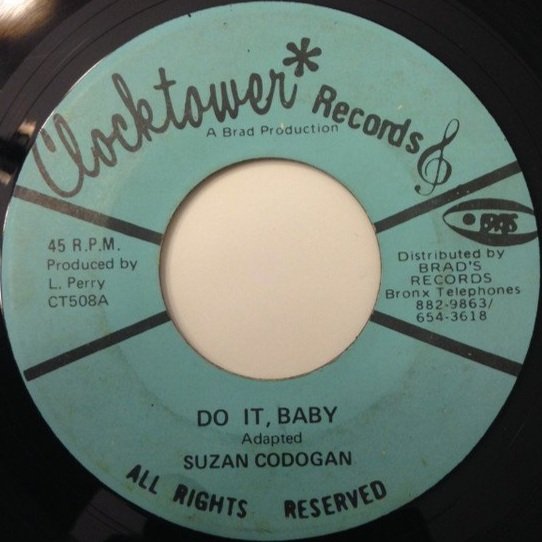

16. Susan Cadogan, “Do It Baby” (1975)

(Perren/Yarian) prod. Lee Perry

Clocktower 508 | did not chart

“Sweet and spicy, come on entice me”

The second of my Jamaican selections for the list, and I only swapped out her cover of Millie Jackson’s “Hurt So Good” for this post-Smokey Miracles cover at the last minute because I hadn’t realized it was issued as a single before then; on Cadogan’s 1976 self-titled album on Trojan — one of my most-listened-to 1970s albums — it’s called “Nice ’n’ Easy,” with a slightly different mix. Which does mean that I’ve left out mento, ska, roots reggae, dub toasting, and indeed all politically charged, liberatory, and committed Rasta music in favor of two helium-voiced rocksteady romantics; but then there’s not a lot of overtly political music elsewhere on the list either, and reducing all “third world” music to anticolonial struggle is one liberal piety I do my best to avoid. Susan Cadogan is not one of the canonical names of 70s reggae, in part because of the usual overrepresentation by men in any music canon, but also because even compared to women like Phyllis Dillon, Marcia Griffiths and Judy Mowatt her high, sweet coo was unfashionable in the roots era, and in fact she was more popular in the UK than in her home island, at least until lovers rock caught up to her in the 1980s. But I love both her high, sweet coo and Lee Perry’s liquid, spacey production style that makes her sound like she’s floating in an astral sea of warmth and desire. The Miracles’ original is a fine, rather pro forma satin-smooth come-on: Cadogan’s “adoption,” girded by Perry’s echoey “ah-wop” rhythm, is one of the sexiest songs ever recorded, all the more so because her performance is so coolly unbothered by the desire expressed in the lyrics. There’s a kind of intellectualized distance from emotion in her singing that beguiles me (I hear it also in Françoise Hardy and Marianne Faithfull, which is one reason all three women are on this list) — I don’t know if the fact that she never quit her day job working in a library even when she was having UK hits is relevant, but it feels like it might be.

First encounter: I don’t remember what prompted me to look into 70s reggae in 2007 or 2008, other than a general sense of embarrassment that I didn’t know much beyond Bob Marley; and I still don’t know much more than that, not in a deep sense. But from the moment I first heard Susan Cadogan I was in love with her voice, and with how Perry’s production style suited her delicate, almost dispassionate delivery, making her buttery soprano just another texture on his wizardly canvas: Susan Cadogan was one of the last 70s albums I spent time soaking in, before my attention became almost hopelessly divided between current pop and earnest sleeves-rolled-up historical research.

Next week: #15-9, in which the choices get more obvious but the writing tries to be more idiosyncratic about it.