Tristany Mundu, Dirar Kalash & ãssia ghendir (13/11/24)

Note: an edited version of this article has now been published on Forward/Scratch.

The opening night concert of Lisbon festival Vale Perdido took place in the Centro Ismaili, whose geometric motifs and orange trees draw attention to the profound Islamic influences in Portuguese architecture, gardens and ceramics. The ceiling of the central meeting room, tonight transformed into an auditorium, features a pattern of stars made up of tessellating hexagons and triangles, while the stage is set up in the centre of four inward facing phalanxes of seats, the diagonal paths between them marked out by vertical orange neon tubes. On the stage are two chairs, one standing completely alone in one corner, facing the other, which has a table in front of it with some hardware and a bass guitar resting on the seat. The house lights dim, a computerised beat plays from the four outward-facing speakers, and the audience — almost exclusively composed, as far as I can tell, of Lisbon art and music scene people like me — shifts in their seats, waiting for something to happen. The beat plays over and over, until eventually Tristany Mundu, musician and multidisciplinary artist from Mem Martins, enters the auditorium and walks deliberately towards the stage, bright red trousers on and trumpet in hand. Rather than take to the stage, he circumnavigates it, stopping to stare at the audience. He has sunglasses on, yet is able to fix several of those seated in the front row with an interrogative gaze. Finally, he picks up one of the vertical neon tubes and walks out of the seated area to the back wall, where he triggers the automated curtains to open. They reveal a wall that is made entirely of glass panels, through which we can see one of the Ismaili Centre’s immaculate patios and a microphone stand. Tristany exits through one of the doors and over the next ten minutes or so sings, wordlessly, and plays the trumpet, mournfully, and climbs part of the concrete lattice exterior of the auditorium, his microphone picking up knocks and clangs that fuse with the sparse music still playing from the four speakers. Because of the layout of the chairs, a quarter of the audience can see straight out, half of us must crane our necks to see, and the final quarter must either turn around completely or accept that this experience will be auditory only. Watching this latter group, there is no consensus. Some swivel awkwardly in their seats. One woman, after some time, stands up to turn her chair around fully. Others sit still, eyes open or closed. I find myself alternately drawn to the tableau through the window and then internally railing against it, petulant at being forced to decide whether to engage with the spectacle. Indeed, there is a surprising amount of chatter in the audience, as if some were still waiting for the performance ‘proper’ to begin. Finally, Tristany re-enters the room, gives the audience the middle finger and passes the neon tube to an audience member with a gesture that indicates she should hold it righteously above her head as he departs. She does not. He leaves. The curtains close once more.

I have described this performance in some detail partly to relive it in all its beguiling detail, and partly to try and give some sense to the interpretations it set off in my head, as these were then carried through emphatically into the next performance by Palestinian musician Dirar Kalash and Algerian vocalist and somatic practitioner ãssia ghendir. What was the effect of Tristany entering the room only to leave it again to perform outside? To refuse the stage and disrupt the boundaries between inside and outside, serious performance and spectacle, business as usual and something new? Perhaps this music, these emotions, were too precious and personal for this cloistered audience of privileged scenesters, comfy in our guestlist seats. Perhaps unfairnesses so deep that words fail to do them justice — racism, police brutality, genocide — transcend the petty etiquette of a festival opening night concert. The issues that matter are going on out there, outside our rarified glass-encased spaces, behind the curtains, trying yet catastrophically failing to penetrate our moribund attention. I think for most of us our motivations for attending events like this are a blend of self-expansion and self-aggrandisement, and the line between those things can be difficult to make out in the social soup. A performance like Tristany’s provides a potent surface on which to project those feelings, to ask ourselves what we are all really doing here, and it’s also that quality that most strongly connected it to the second part of the programme.

The lineup for this concert originally promised a collaboration between Palestinian musicians Maya Al Khaldi and Sarouna, founders of the womxn-led independent record label and artist space Tawleef, and Palestinian visual artist Dina Mimi, but in an inevitably ominous turn of events, we are informed a few days before the concert that the trio are unable to travel to Lisbon. The emailed statement reaffirms that the event remains essential to the narrative of the festival’s programme, and that Dirar Kalash and ãssia ghendir will “pass on the message” with their performance. So with Tristany’s peremptory absence still lingering in the air, the duo take to the stage, Dirar looking like a beatnik in black hoodie, black beanie and spectacles, ãssia a kind of punk nun in leather trousers and untucked school uniform shirt and tie, a head covering over their buzzcut. ãssia brings a fragrant incense burner with them and paces around the stage briefly, smiling once in our direction, before settling on the solitary chair, bolt upright, cradling a microphone. Dirar, with his bass guitar flat on his lap, seems to sink bodily and mentally into the task before him, until his hands begin to delicately coax notes, noises and echoes out of the neck, body and then strings of the guitar. These are fed through a sound card, a magical effects box that sputters with static every time he touches it, and his laptop, which later will also process ãssia’s voice. But the latter’s initial contribution is not much more than a sharp breath, hissing, keening, taking its time to flourish into full vocalisations, wordless like Tristany’s, rising and falling in waves over Dirar’s improvisations. ãssia’s face is a miracle to observe as they sing, seized sequentially by emotions from grief to rage to astonishment, lapsing occasionally, through my eyes, into an almost parodic tragicomic mask. The moment I posit to myself this potentially arch dimension to the performance is the moment my brain is flooded by questions about my relation to art from other cultures, my ability or inability to take it at face value, the layer of cynicism, sensitivity and shame that sits suffocatingly over our capacity to simply relate to others. The luxury of these prevarications. It’s impossible for me to know if there is a satirical element to ãssia’s performance, but the thought persists and contaminates my reaction to Dirar, whose demeanour and improvisations for stretches really do seem to me to be affectations, designed expressly to appease Lisbon art scene sensibilities. Not as if those sensibilities are anything special. In my temporarily twisted reading, though, they seem to be saying that these motions must be gone through, the vultures must have their culture, before the real message can be received. But then I think: why shouldn’t Palestinians also indulge in relatively obtuse improvisation, if they want to, just like anyone else, just like us? Why shouldn’t Palestinians also live their lives free of occupation and bombardment, have their rights upheld, just like anyone else, just like us?

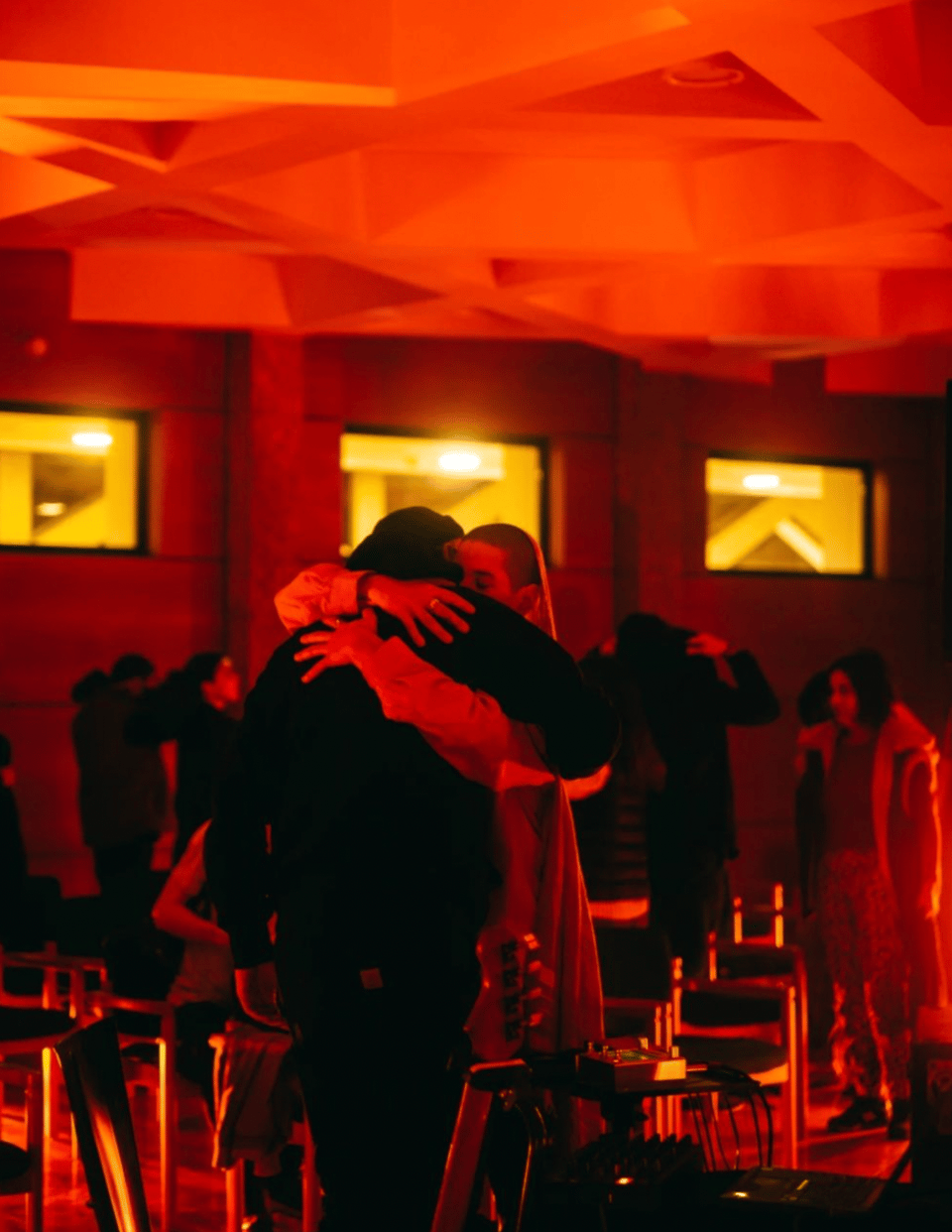

This psychological step, from a relatively innocuous navel-gazing thought in one moment, to an excruciatingly real, political and existential thought in the next, occurs again and again as ãssia’s voice crescendos and they stand up and walk around the stage, then leave it to circle the audience, much as Tristany did, now visible now not, their wordless litany increasingly distorted by Dirar’s machines into feedback and static. The outside world continues to intercede. The architectural shell of the hall, especially its starry ceiling, rattles in different places with the frequencies of Dirar’s guitar. At one point one of the stage lights fries inexplicably into ebullient flashing, drenching the room in incongruous disco technicolour until, in a moment of pure bathos, one of the lighting team pulls the plug. Dirar’s laptop, unattended, switches to screensaver, and it takes him several attempts to type in the password correctly. These moments seem to say: there’s always some petty bureaucracy of daily life, some distracting practical barrier that no one is sure who invented or why, to impede the message.

The performance must have been going for almost 45 minutes by this point and again the question of attention arises, as mine frequently wanders. I ask myself: how entitled do I feel to being entertained? Then, given enough time to ask myself that question, I begin to sense, and accept, another one: don’t I have an obligation to bear witness? The first part of Dirar and ãssia’s performance, like Tristany’s, has provided a powerful yet ambiguous mirror for interrogating these questions. The next part, however, brings things sternly into greater focus, as ãssia kneels now silent, next to Dirar, who puts down his guitar and begins to trigger field recordings and other sounds from his laptop. Grinding of metal, children chanting, squalls of noise, possibly munitions, possibly something else entirely, Dirar, head down, rocking back and forth in his chair for a minute or two at a time, before looking up and once again tweaking the sound issuing forth from the speakers, then back down again, rocking. Any notion of satire is long gone. The audience remains split in their reaction: some seem rapt, staring frozen at the pair, or with eyes closed; others still shuffle in their seats, looking around; still others take the opportunity to make a discreet exit. The lighting team set the orange neon tubes pulsing, rather unnecessarily, I feel at first, but then the play of the lights on the ceiling draws my attention, the hexagons and triangles thrown into shapeshifting relief like the rushing onset of acid visuals. It’s not as if I start thinking of the concert as a psychedelic experience, but it’s in this moment I truly acknowledge that it has been intensely psychoanalytical, about boundaries, about speaking and not speaking and the insufficiency of language, about the self and others, about symbols and layers of meaning, about feelings disowned and projected, about integrity and disintegration, damaged objects and the work that might be done to repair them. A glass wall, a starry ceiling, a wordless litany, a middle finger.

After a further 10 minutes or so, the second part of the performance ends to applause, but this is cut short by Dirar who, having taken the microphone from ãssia, finally addresses the audience directly. And this is the third iterative layer of the analysis, the synthesis in fact, where the reverie and iconography and back and forth projections of the preceding hour and a half are finally put into plain, albeit halting, words. Darir insists he is not here in his capacity as a musician, or because this is a music festival. These statements imply more directly what Tristany had invoked through his performance: an opening night concert is not enough, in times like these, unless it becomes something more than that. But again, despite Darir’s matter of fact delivery, I can’t help hear a double layer to his statements, which seem to satirise the normalisation of patent falsehoods into which Gaza’s reality is translated daily by the IDF, the US and UK governments and media platforms alike: we do not target civilians, only terrorists; we are not preventing aid from entering the country; we are acting in self-defence. I am not a musician. But this isn’t what Darir is trying to get at, and his words are chosen carefully and delivered with immense feeling, finally verbalising the ineffable elements of his and ãssia’s performance as he explains that, while the more recent sounds we heard were taken from news reports on his phone, the earlier recordings, including the sound of live explosions, were made when he lived in Ramallah. His intention in combining these sonic records and presenting them here tonight is to bring Gaza to life in other places, so that it survives through sound and in the minds of those who hear it. This act inscribes a Palestinian culture and identity that, despite systematic efforts to eradicate them not only in Gaza and the West Bank but also, now, in Germany, will live on.

“Bombs drop there so that they do not drop here, but they might,” Dirar finishes. “We can’t stop the genocide. Palestine will be free.” This evening’s programme, performances and setting were remarkable: not a music show, nor the opening night of a festival, but a declamation that for one moment collapsed the psychic boundaries between us and them. It is on all of us to make sure the curtains remain open.

Add a comment: