Track-By-Track: Ghostcast #19

The main section of this post has been paywalled - if you would like to support my writing and have full access to posts like this one, plus tracklists and downloads, you can sign up for a paid subscription here:

This is an entry in the Track-By-Track series for my mix for The Ghost - see the index.

Track-By-Track is a series that looks back at records you will have heard in my mixes, one by one in the order they were played. Who made them, and when? How did I come across them? And what do they make me feel?

Though I can’t be sure, I probably came to this record via Daryl B, whose name popped up regularly on credits for the UKG tunes that were becoming popular in the London ‘digger’ scene of the early 2010s. For example, the remix EP of Carroll Thompson’s ‘Too Late’, produced by MJ Cole, had his DB stamp on it, while the DB Selective release on V.I.P. (Very Important Plastic), also with MJ Cole, was an example of a record that by that time was already a bit too expensive for me to consider buying. (I got the Pisces, Greg Stainer and Jason H releases on the label instead.)

If I had to guess, I must have been looking back through Daryl B’s production credits on Discogs and saw he’d been involved with the Tooo’s Company label. ‘Release Yourself’ was their first record, put out all the way back in 1992. Here’s the original:

I was immediately drawn to the stop-start intro with those heavy kicks dropping in and out, and then the surprise harmonic modulation almost 5 minutes in — an unexpected heartstring-pulling coda to an otherwise straight-up banger. The Lazondub version was never really my thing — harmonically messy and overly dense compared to the original — and then there’s the instrumental, which is fine as far as these things go, though we all know that instrumentals are fundamentally homophobic.

The Release Yourself (Remix) EP was released three years after the original, in 1995. Despite liking the original so much, for some reason I didn’t get hold of the remixes until 23 March 2020 — two weeks into the first lockdown and, though I didn’t know it at the time, a moment that marked the beginning of the end of my relationship with Discogs (more on this below). Not all of the remixes were on youtube and I was curious to hear what they sounded like. It turned out that the Tooo’s Company remix was a housed-up banger version so I decided to put it in this mix for The Ghost. Coming in just after the hour mark, it is the only truly classic house moment in the set, letting out the pent-up energy I’d built up to that point with its joyful piano and that big vocal: “Release! Yourself!”

It’s a long-ish track (for me at least) at 6+ minutes, and the back half gets pretty busy before finishing with one of those crescendoes and fades that doesn’t really lend itself to a smooth transition out. You have to do all the work with the EQ to get rid of it before it just ends abruptly, and I just wasn’t in the mood for that. So instead I cut it short, mixing out of the mid-track break where you just have the pads, strings and clap. This approach also felt in keeping with the more restrained vibe of the podcast as a whole and kept the momentum going into the final half hour.

Here’s the Tooo’s Company remix, which I’ve had to upload to youtube. And below, a bit of a trip down memory lane prompted by RA’s recent film about ‘digging’…

Three’s A Crowd - Release Yourself (Tooo’s Company Remix) [Tooo’s Company, 1995]

Discogs Digression

I mentioned above that March 2020 marked the beginning of the end of my relationship with Discogs. For the previous 12 years or so I’d been making multiple orders per month through the platform in my version of online ‘digging’, which at the time I would often tell people was preferable to going to real-life record stores. On the internet you didn’t have to deal with potentially grumpy counter staff or other customers hogging the listening decks. And there was no feeling of obligation to buy something even if the stock was not that interesting. Of course I would occasionally go to real-life record stores, especially when travelling, but in general I preferred the anonymity and comfort of Discogs.

There was also an element of obsessiveness/acquisitiveness to my digging in those early years. A desire to own all releases (or at least every good release) by a newly-‘discovered’ artist or label (that is: newly-discovered by me), which was of course enabled by Discogs’s extensive and interlinked catalogue system. So I would go down the usual rabbit holes that most Discogs users are familiar with. That’s one of the subjects of this recent RA film, in which I appear briefly — and before I continue, I encourage you to watch the film properly because it covers much broader ground than what I’m talking about here. (Particularly interesting to me is the discussion of the historical reasons why records made in the 90s sound so particular, and Titonton Duvante’s reluctance to be seen as a ‘legacy act’ — big up Titonton!)

So. Discogs and me. Me and Discogs.

My sales history tells me that in the calendar year of 2012 I ordered 150 records through the site, a total spend of around £1,000. Let’s dig a bit deeper into My Year On Discogs 2012, with a bit of commentary that comes with the benefit of 10 years of hindsight.

First up, the expensive records. Back in those days I was working a well-paid corporate job in London and my rent was more than manageable, so I had a lot of disposable income. The most expensive records I bought in 2012 are quite illuminating: .g’s The Raw EP (£80); Nail’s Big D’s Lounge LP (£40); the Deep Space Network Meets Higher Intelligence Agency LP (£26); Stephan-G’s Lod EP (£60) and Jesper Dahlbäck’s The Persuader EP (£35). Here the influence of my friend Andrew is plain to see: he was the one playing these records at house parties, afterparties and, increasingly at that time, at public parties like Toi Toi in London. I had never heard of Svek or DiY or many other things before meeting Andrew and it’s fair to say that most of these records that he was playing belonged — and still belong — to a category of all-time greats. So I wanted my own copies and was willing to spend the money to get them.

Many of the above records and others I bought that year have been reissued in some form or another since then, some of them not that long after I shelled out big bucks for them. I ask myself if this provoked — in the rather sensationalist words of the RA film — any existential crises? I don’t think so. Maybe some slight pangs when I thought about the other records I could have spent that money on. But in each instance of me deciding to drop that cash, I know it was because I really wanted the record, not as some kind of prize or coveted item to hide away in my magpie’s nest, but to play it out and to do so for years to come. And the fact that I’ve done that with all of these records — indeed, almost all of them have had outings in 2023 — shows that they’ve given me over a decade of solid experiential DJing pleasure. Money well spent, in my view.

The next category is also solidly positive as far as the benefits of ‘digging’ go: the bargain finds, which I count as records that I got cheaply that were either already expensive or soon to be so, and that became staples for me over the coming years. Here I’d highlight: Derek Carr’s Copperbeech EP (£12, and part of one of only a handful of completist drives I undertook, which I’ve mentioned before); Moodymann’s Silentintroduction LP (£25); Kickin Kim K’s So In Love EP (£10); UR’s Electronic Warfare LP (€7); Lil John Coleman’s Feel Good EP (£2.75); Ricardo Villalobos’ Alcachofa LP (€12).

Of course several of those LPs can be bought a lot more cheaply on CD (or indeed on bandcamp), and with my 2023 hat on I’d have nothing against just getting the CD and ripping it for the files. But there is also no doubt that I feel a kind of warm satisfaction having these records on my shelves and — yes — taking them out to play at gigs. They’re just so hefty and reassuring. Admittedly I haven’t reached for the Derek Carr record for years, but Electronic Warfare is an almost constant companion on the road, as is the Lil John Coleman record. I’m glad I got them when I did.

(Hilarious side note: when I received the UR double LP in the post from Sweden there was quite a lot of surface noise on ‘The Illuminator’, so I asked for and, if you can believe it, actually *got* a 3€ refund, bringing the total cost of that album to 4€.)

(Less hilarious side note: I sold the Kickin Kim K EP for only 8 quid a year after I bought it, and I’ll never forgive myself for it because it’s such a banger. What was I thinking?)

With those out of the way, now we’re getting to the categories that I feel less wholesome about when looking back at my days as a ‘digger’.

First off, the so-called ‘blind’ purchases, where I’d take a punt on a record based on the label or artist (or artwork or name or whatever mad criteria would enter my head) without actually knowing what it sounded like. I did this semi-occasionally and never systematically or comprehensively, like some people buying up an entire label’s back catalogue. But of course perceived rarity did play into my decisions. For example, after trawling through his labyrinthine back catalogue, I was determined to get a copy of this Hakan Lidbo record made under a one-off alias. It was a white label that had never been sold on Discogs, on a label called Lap Dance and with the artist name Dirty Harriet — of course I wanted it!

My email history tells me I first tried to get it through the now-defunct Gemm.com, but they sent me the wrong record, so I then ordered it through the also-now-defunct music-on-click.com and finally got my dirty mitts on Dirty Harriet. Is it a good record? Well, it’s not bad. The A and B1 would probably go down pretty well with the current wave of trancey-breaksy-house people, but they’re not really my bag. The B2 is the one I instantly liked and still roll out from time to time, a wonkily jubilant minimal house track that sounds like very little else in my collection.

So that Hakan Lidbo record was an example this obsessiveness and desire for the obscure leading me to a record that’s brought me a lot of joy over the intervening 10 years. Fair play. But of course there were many more instances where I bought a record blind and it was rubbish. Now that I’ve been playing more digital music, when I look back at that way of buying vinyl I just see so much waste: wasted time, wasted shipping materials, wasted vinyl languishing on the floor, eventually destined for the bin…and for what? Finding the one record out of 20 that would stand the test of time? It all feels so profligate, with no sense of camp or fun to justify the profligacy. So when I hear about people ordering tens if not hundreds of records ‘blind’, in the hope that one of them might be listenable, I just shudder.

I also think about how paltry the resulting story behind that one record will be when they tell it. Of course the missing element in blind buying — or, for that matter, rabidly trawling through a random youtube channel for hours on end — is the storytelling aspect of looking for records, the personal history of how it came to you and what it means. Maybe you heard someone playing it at an afterparty and they gave it to you? Maybe you found it in the Marylebone High Street Oxfam? Maybe you heard your favourite DJ play it and when you asked them what it was they told you their personal history with it too? For me all of that is so important. Perhaps it’s a bit like dating: “we met on Grindr” doesn’t have quite the same ring to it as “we met on the dancefloor at Horsemeat Disco while ‘Starchild (Spirit Of The Night)’ was playing”. Both are legitimate ways of meeting people, but to me one of them feels a bit less transactional from the get go. Of course this is me showing my age, and I know many people who embrace the numbers game without any qualms. But I would always prefer something more organic and human.

That being said, I also won’t deny that some of the enjoyment I derive from having that Hakan Lidbo record comes from the knowledge that I have it and very few other people out there have it too. It’s like having unreleased tracks. It’s kind of nice to feel that exclusivity and scarcity and “ownership”, because we’re trained from an early age to prize those things. (I’m avoiding using the ‘C’ word here on purpose, but you know what I mean.) I guess that’s why some DJs apparently buy up all available copies of a record so that they can be the only person to play it. (Really guys?) But that attitude is also at the base of many of the issues I see with ‘digging’ culture, as I and others mention in the RA film.

I can give a personal example of how that market-minded dynamic played into my record buying back in 2012, in the shape of the Affected Music catalogue. My Affected Journey™ went as follows:

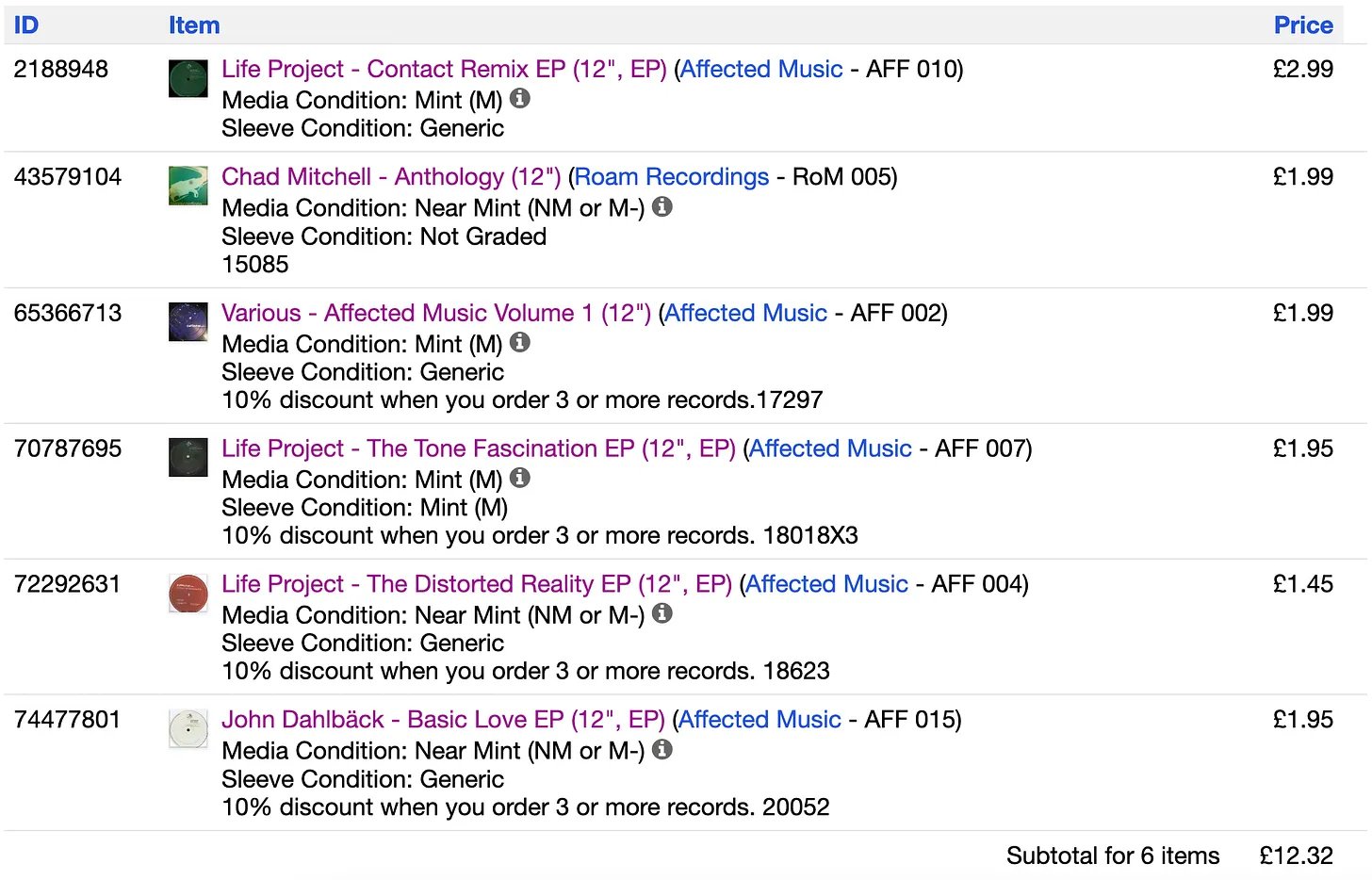

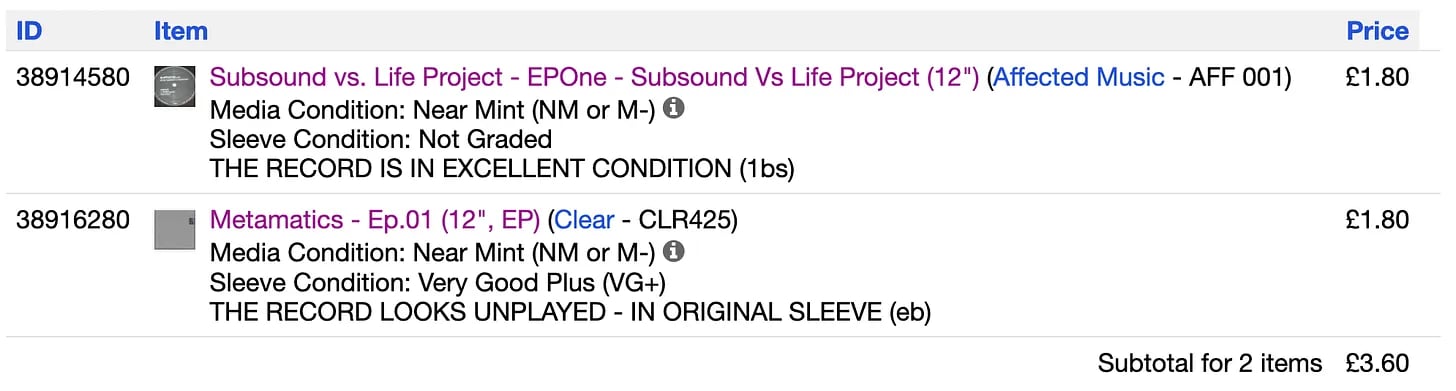

I must have stumbled across or got tipped off about the label in late 2012, so I went on Discogs and made these two orders:

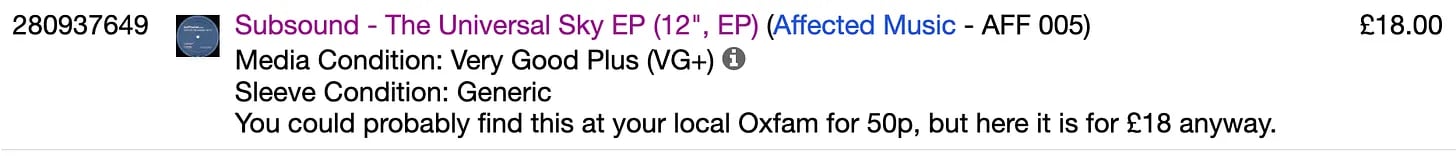

I played the records for a few years, during which time they became more and more trendy and sought after. Then there came a point where I realised I could sell them for a lot more than I bought them, and asked myself: am I into them enough to keep them? The answer was no, so I sold all but the John Dahlbäck record (which I still have here on my shelves, because I just love the B2) for between £13-£18 each. In my defence, I at least had a sense of humour about it when writing the listings:

Of course if you look at these records on Discogs now you would say I undersold these big-time, since they are all currently going for around €30-€50 (except, perhaps tellingly, the only one that I kept). And it really does seem like people are buying them for that much, which I can’t quite fathom since it seems to me that this kind of tech house has become distinctly untrendy, at least in the circles I move in. Whatever, I guess the point is that because of a sudden trend in 2012, these records went from literal £2 bin material to being inaccessible to anyone who doesn’t have a load of money, barring a reissue project.

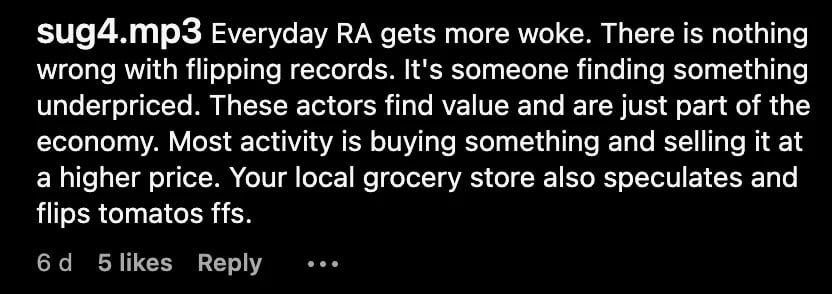

So what was the result of My Affected Journey™? I got hold of some better-than-average records, had some moderate enjoyment from playing them out for a few years, then made about 60 quid selling them on, contributing to the generalised inflation of prices on discogs and keeping the British postal system busy. Overall, looking back as my 2023 self, I don’t view any of this with much pleasure, let alone pride. As Vera says in the RA film, it just feels like it was about the money, not the music. You do wonder how people who make a living from playing the Discogs market (again, I’m avoiding the S word here) sleep at night. Though some of the internet commentators seem totally fine with it:

Now, if you’re an actual human being, that transactional or scarcity-based way of looking at value is of course not the be all and end all of records or, indeed, life in general, and it’s important to draw the line somewhere. In fact I believe quite strongly that where you draw the line tells the world a lot about what kind of person you are. It’s that human part, the experiential value behind a record as opposed to its market value, that I would hold up as the antithesis of the kind of obsessive, mechanical digging that characterised my — and many people’s — relationship to records in the scene and period being discussed in the RA film. These days I couldn’t care less if a record is rare or exclusive or whatever…I just want it to have a story. It’s similar to why I place strong limits on the amount of new digital music or promos I listen to: I don’t want sheaves of files sitting on my hard drive waiting to be threshed, processed and left to decay (unless it’s mulch house, of course). I want lasting personal meaning.

One final anecdote, though, just to play devil’s advocate to that last statement… Back in 2012, I also decided to go through the Fiji Recordings catalogue. I think Andrew, as a fan of The Timewriter, was playing the Journeyman release from the label, and it was also home to Laid (of the then-ubiquitous ‘Punch Up’ fame) and, of course, Hakan Lidbo. I bought a bunch of the Fiji records — those already mentioned plus Hollis P Monroe, Morgan Page — and played them out for a couple of years before gradually selling them all again, for not much more than I had bought them. The only one that’s still on my shelves is Morgan Page’s Lonely Night EP, which up until this year I had barely reached for again.

Then earlier this summer I saw livwutang posting about playing another Hollis P Monroe record at Club Toilet in Detroit, and it triggered a memory of Fiji and my flirtation with the label so many years ago. So I dug out that Morgan Page record and played it a couple of times at parties. I also heard someone else play it — maybe Heels & Souls? — adding to the web of associations. It felt good, a sort of full-circle moment that illustrated how some of those old forgotten records remain relevant and can still move me, despite all the changes I’ve been through in the meantime.

During covid, when I didn’t have any gigs, I pretty much stopped buying records on Discogs because I didn’t want them sitting on my living room floor judging me for not playing them out. And since gigs started again I’ve been playing more and more digital, for various reasons I’ve discussed elsewhere. I still like going to actual record stores when I travel, but rarely have much space in my luggage to bring any back with me. The upshot? I actually haven’t bought a record on Discogs since July 2022. I guess you could say we’ve semi-consciously uncoupled.

Yet, right now, looking at the Fiji page as I write this newsletter, I see a comment relating to this mysterious release by Sandoz (5), and my heart rate literally increases a little. It’s not the same Sandoz as Richard H Kirk, but for a brief moment there was the possibility that it could be. And it’s a limited run white label that never made it to full production. There’s a youtube video and, frankly, it sounds sick. There are two copies up for sale at €50 and I think to myself…

Well. I’ll add it my wantlist. You know, just in case.

Add a comment: