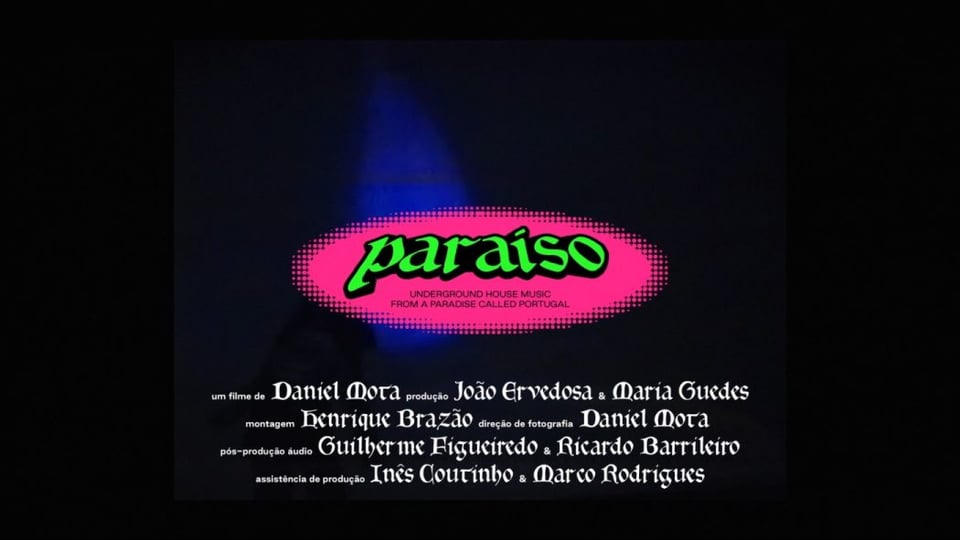

Paraíso (Film Review)

This is a review of Paraíso, a documentary film produced by the team behind the long-running archival project, radio show and event series of the same name, which premiered at Lisbon’s Cinema São Jorge on Sunday night as part of IndieLisboa’s music section. After two sold-out screenings, a third session has been scheduled for Saturday 10 May at Culturgest.

I had heard about this film a couple of months ago when I sat next to Shcuro and Maria Amor at an artist dinner for Outra Cena. Compiled by the duo from over 100 hours of footage — both archival and from interviews/conversations between main players shot over the past 10 years — and thousands of photographs, directed by Daniel Mota and edited by Henrique Brazão, the film tells the story behind the infamous phrase “Underground house music from a paradise called Portugal”. Like many places across Europe, Portugal had a dance music boom in the 90s that saw the biggest international names playing in the most provincial of towns almost every weekend, followed by a precipitous fall in the 2000s. But among other things Paraíso makes a case for Portugal’s unique influence on a particular strain of early-to-mid 90s dance music — what Danny Tenaglia describes in his interview as “not techno, not house, I don’t want to say trance, but something that put you in a trance-like state” — as a result of rave exchange between Portuguese and American DJs and promoters.

The stage for this exchange is set in the opening section of the film, beginning with a 1992 clip of newsreader José Rodrigues dos Santos — a kind of portuguese Andrew Marr — reporting on the new “raven parties” (sic) influenced by the second summer of love in the UK and now taking Portugal by storm. We are gradually introduced to major players from the nascent scene through interviews and conversations filmed in evocative contemporary locations, including Lux Frágil and Planeta Manas. For an outsider like me, only a few of the faces and names register, but with tonight’s audience being a full house of Portuguese dance music scenesters from the past 40 years — with many of those featured in the film present as guests of honour — each new character is greeted with a whoop of recognition and applause. There are the Leite brothers, Luís and Paulo, who were already established DJs when the rave wave broke, and who paint a picture of the club scene at the start of the 90s. While clubs like Kremlin and Alcântara-Mar were already established since the 80s, DJs had to play rock music until the final hour of the night, when there was a window in which to put on some acid house or similar. Most if not all nightclubs had to close up at 4am. This establishing section of the film was a riot for the Portuguese crowd but could get a bit repetitive for audiences elsewhere, as most of the interviewees have similar things to say as they are introduced.

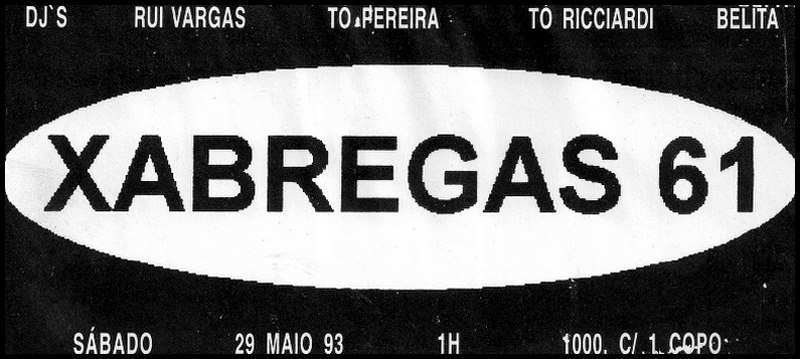

The film moves on to cover the emerging rave scene, starting with a shift out of the city centre clubs and into off-location warehouses in Xabregas in the East of Lisbon, where the parties would carry on into the late morning hours and the outfits and behaviour became significantly more unhinged, as the charming archive photographs testify. (Funnily enough, a more recent wave of afterparties began in Xabregas and further East soon after I arrived in Lisbon in 2014 and has since grown into a concentration of more regular spots in the area.)

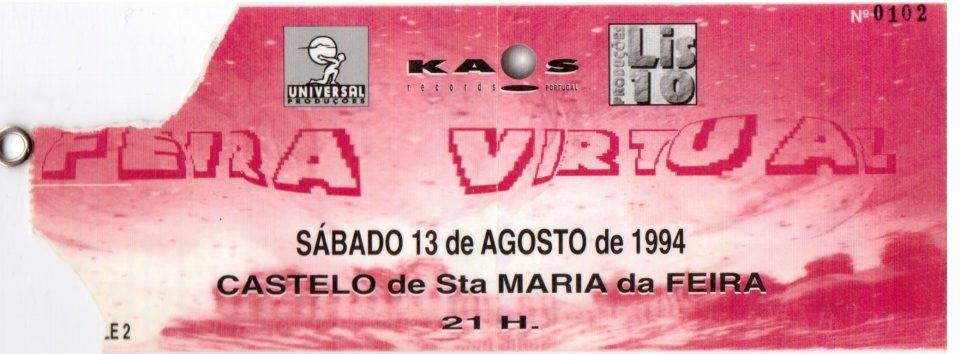

As the scene gathered pace, promoters like the late António Cunha — who is regularly namechecked in the film as one of the main driving forces behind the boom — made plans to hold bigger out-of-town raves à la London’s M25 circuit. Of course Portugal had a countryside full of convents and castles waiting to be used for just this purpose, and as these events began to welcome international guests — like Tenaglia and Jaydee at a castle rave in Santa Maria da Feira in 1994 — the aforementioned cultural exchange gained momentum. The footage of this ‘Feira Virtual’ — which, along with a convent rave the year before, is mentioned as a turning point by many of those interviewed — is fabulous, from the seductive allure of the nighttime dance performances through to the morning shots of bleary eyed, wobbly-legged stragglers drifting around the perimeter of the castle like a zombified medieval circus troupe.

Three of the four members of The Ozone, a band in the vein of The KLF or Altern8, talk about how they had been jamming in the studio one day in the weeks leading up to the castle rave, when Cunha asked them if they could do what they were doing live on stage. “I said yes, because how could I say no to the boss?” explains one of the three, and we are shown the quartet on stage in the middle of the castle, in white boiler suits and head torches, tonking out acid techno via machines and giant computer monitors. Tenaglia and Tribal Records’ Rob di Stefano had apparently never seen anything like it, since, as one pair of portuguese DJs drily observes, they simply don’t have castles over the pond. In his interview, di Stefano describes it as a lifechanging experience, and it set in motion a series of collaborations between his legendary NYC label and artists from the Portuguese scene.

Meanwhile back in the cities and towns new spots were opening, like Climacz in Lisbon, which ran from 6am to midday, and existing venues were extending their hours late into the morning. Two of the most compelling interviewees are the Alcântara Dancers, a couple whose tattooed bald heads are an instant giveaway to their raving past. They describe late morning club hopping between their workplace Alcântara-Mar and other venues, and the new ideas they would dream up to shock the dancefloor, including walking naked through the bustling crowd. “Could you do that today? No!” one of them exclaims, wide-eyed at his own daring. The phenomenon of how raves spread to even the more provincial parts of Portugal is touched on by another DJ, who describes an average weekend itinerary: “I’d play three times in one night, first in Beja, then up to Coimbra, and then at an afters in…(pause)…Famalicão! I turned up late to that one.”

This is one dimension of the story I’d have liked to hear a bit more about. I remember a few years ago seeing a short film by Portuguese director Jorge Jacomé, Fiesta Forever, which revisited (in 3D reconstructed form) some of the large discotecas that had populated Portugal’s coastline since the 1980s and variously shut down in the 90s and 00s, now abandoned and overgrown (see these photos of Green Hill in Foz do Arelho, for example). I’ve heard stories about huge parties down south in the Algarve and up north at Figueira da Foz near Porto (there is one stunning photograph of an X-Club rave, the sun rising in the background of a thousands-strong crowd), and clubs with five or six dancefloors. I guess from the perspective of this film, this is perhaps a more mainstream lineage, running in parallel to the underground story it wants to tell.

Hand in hand with the parties themselves, there is of course the music. The film goes into the impact of ‘So Get Up’ by Underground Sound of Lisbon aka DJ Vibe and Doctor J (aka Rui da Silva, later of ‘Touch Me’ fame), with a memorable vocal by Darin Pappas that many thought came from an old film, but was actually a poem he read out once while they were soundchecking the instrumental. The first time that resounding “SO GET UP!” rang out in the cinema auditorium on Sunday, I got shivers down my neck. Released on António Cunha’s label Kaos Records in 1993, Vibe and Paulo Leite took some copies with them to NYC and managed to get one into the hands of Junior Vasquez at the Sound Factory, leading to it being signed by di Stefano at Tribal.

The various recollections of this event are an excellent illustration of how dance music myths are made. Leite sketches the scene at the Sound Factory, where a security guard acted as middleman between them and Vasquez in the raised DJ booth. Nuno Cacho — another entertaining interviewee — ups the drama in his second-hand retelling, explaining how the record had to be physically hurled into the booth from the dancefloor to reach Vasquez, who then went on to play it no less than three times that very night. di Stefano relates how Eightball Records had already put in an offer for the record, but he was able to swoop in before that contract had been signed with an offer of his own, including a promised sweetener of remixes by Vasquez and Tenaglia. How could the Tuga trio resist? Cacho also refers to distribution deals between Kaos and other big labels. One photo shows Luís Leite wearing an UMM t-shirt, and indeed his 1995 release as LL Project was picked up by the Italian powerhouse, but apart from a couple of other records being put out by labels in Germany and Belgium I can’t find much evidence on discogs for major reach beyond the hookup with Tribal/Twisted.

There’s an amusing section of the film focussing on drugs, starting out with several coy reactions on the part of the DJs being interviewed whenever the subject is raised. “Well, I witnessed it…” demurs Paulo Leite to uproarious laughter in the auditorium, before he goes on to explain with perfect recall the cost of an ecstasy pill in 1995. “I wouldn’t know,” replies DJ Morgana with a twinkle in her eye, “I never paid for them”. Queen! Of course the rave scene always has its shadowy side but here it is present only indirectly, be it through the Alcântara Dancers referring to earlier dark periods in their lives, or The Ozone speaking movingly about the fourth member of the band, Eduardo Melo aka Dice, who died in a car accident just as they were hitting their stride. Indeed, the raucous footage of ravers barrelling down the highway at 9am, clearly off their faces and having the time of their lives, is both exhilarating and unsettling.

I had one broader issue with the film: because the only verbal narrative vehicle is the interviews and conversations, one occasionally feels the scope of what can be said is limited. For example, the decline of Portugal as a rave paradise is something discussed only tangentially, leaving us only with a somewhat misty-eyed nostalgia. But you can kind of piece it together from the storyline and anecdotal fragments. In 1998, Portugal hosted the World’s Fair, known as Expo 98, the principal vestiges of which are visible to any visitor who today visits the Parque das Nações area around Oriente, still home to the aquarium, cable car and international fair. That was the same year that Lux Frágil, Lisbon’s foremost clubbing institution to this day, opened in Santa Apolónia, while another mega club, Vaticano, opened the following year in Barcelos in the North. (There was a ripple of recognition around the auditorium when the latter was mentioned, but interestingly I had never heard the name until now.)

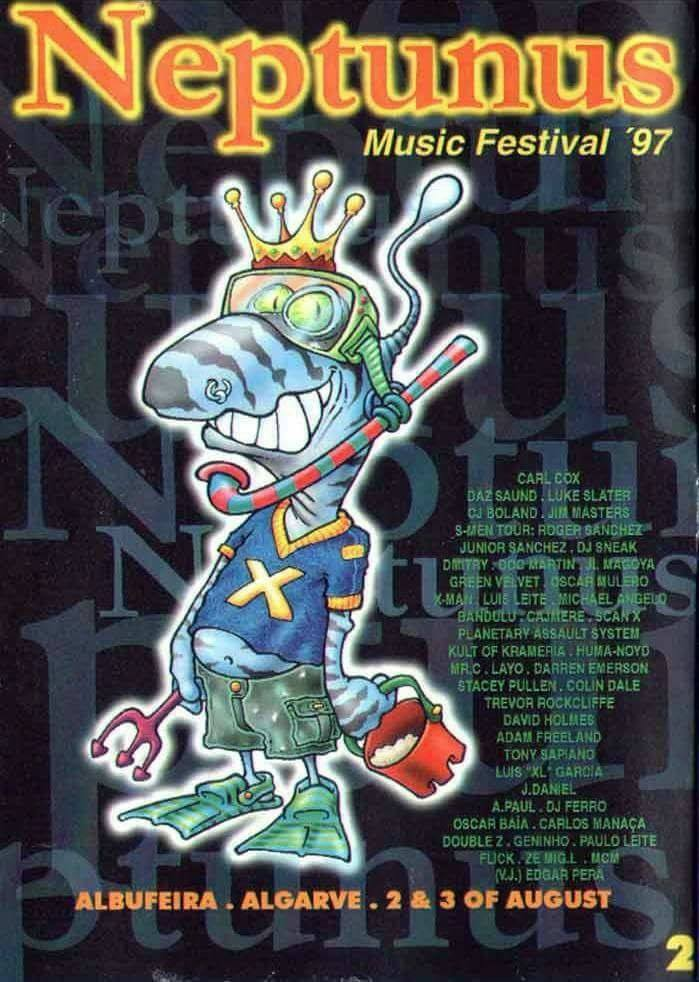

DJs and brothers XL Garcia and Wla Garcia have an exchange about Festival Neptunus, the first major dance music festival in Portugal, held in Albufeira in 1997 and apparently put together at the behest of the Expo 98 organising committee. Warning against romanticising the event, XL is careful to note the shortcomings of the organisation (one suspects some artists did not get paid). The account given in part two of Gabriel de Oliveira Feitor’s wonderful article ‘A Brief History of Dance Music in Portugal’ bears that out, identifying Neptunus as a microcosm of the broader reasons why Portugal’s rave Paraíso came to an end: too much ambition, not enough demand, and a contamination of the original rave spirit by mainstream and institutional interests, drugs and violence.

One discogs comment on ‘So Get Up’ captures many of these threads from an outsider’s perspective:

Reading this review after watching the film, it strikes me that Paraíso depicts something wider about modern Portugal, something that speaks to the national psyche, about how things here are always a bit late, a bit second-hand, and ignored by the rest of the world. It’s difficult to deny it when Frank Maurel — a delightfully laconic interviewee — says that part of the issue is that Portugal has never really valued its own homegrown cultural production. Indeed, right this moment we are witnessing the shuttering of venue after venue, and police intimidation of DIY spots like Planeta Manas that are surely the closest thing we have in 2025 to the free spirit of those early 90s events. Indeed, watching the footage of the Alcântara Dancers and hearing that anecdote about them walking naked through the club, who wouldn’t make the obvious connection to CURVS, the body-positive, sex-positive party at Manas that has been raided by the police multiple times over the past year.

On Saturday, the day before the Paraíso premiere, an association named QRAVO held a demonstration in Lisbon to protest the increasingly oppressive policing of queer and trans bodies in the city’s nightlife. It’s difficult to know how diverse or safe those raves really were for everyone back in the 90s, and there’s surely more than enough fluff out there in the history of dance music about “PLUR”, though thankfully there is a minimum of it in this film. With a handful of exceptions, the demographic of people interviewed in this film is solidly white, male and straight, reflecting the homogenous make-up dance music’s professional milieu then and, still to a degree, now. Yet, on Sunday night, watching the footage from the Xabregas warehouse parties or the ‘Feira Virtual’ in the castle, I was instantly reminded of the motley crew of queers and queens at Saturday’s protest, righteously dancing in the rain. Can this pursuit of something revolutionary and inclusive, based on mutual respect and a celebration of difference, survive in today’s nightlife “marketplace” (shudder)? One thing Paraíso shows us is that those 90s gatherings were perhaps achieving, albeit naively, some of what today’s revolutionary-minded ravers have to work so damn hard for.

Add a comment: