Chaos And Form (Guest Post By Bleimann)

“No One Dies From Love”, The Best Pop Song Of 2022

December 2022: I’m on my way to a church backroom to try to get my life back together again (OR to get my life back together, again; OR to get my life back, Together Again). I put my headphones on and play “The Greatest Love of All” at full blast. Nobody is on the street so I sing out loud as I walk. I think: this is one of the few moments in your life where THIS level of melodrama is actually warranted. Silver linings.

What really happened here? I wish I knew.

In 1922, the German Psychologist Kurt Koffka published Perception: An introduction to the Gestalt-theorie, one of the foundational texts of Gestalt Psychology. In it, he proposes a radical way of understanding the way we process the world around us. Instead of focusing on our reaction to individual stimuli – a table, a chair, a lover – we must understand our inner worlds as the result of a process of coming to grips with an entire field of perception. Every moment of every day, we are surrounded by an impossibility of stimulation. To bring sense to it, we group things together, eliminate things, see movement or stability where there is none. The result is something we can work with, or work through. But in the process, we take short cuts, find connections where there are none, rely too heavily on our prior expectations, gained from experience. To attempt to reach the stimulus itself is a fool’s errand; we might modify or adapt our perception, but it will have to do as a perpetual approximation.

In 1941, Erich Fromm would come to similar conclusions on a societal scale in The Fear of Freedom. Industrialisation, the decline of religion, and capitalism had caused the breakdown of old certainties. In a feudal society, a baker’s son would succeed him as town baker. Uprooted into hellish cities, the industrialised worker lost his old certainties, without new ones to replace them. In theory, he was faced with the dilemma of freedom. In practice, he still had little freedom to define his own path in the world; he was left only with freedom from old constraints, without the possibility of new stabilities to give order and meaning to his life. Confronted with this unbearable freedom, authoritarianism grows: the desperate seek new, decisive truths, throwing themselves behind leaders who promise simple lies to those who sacrifice their freedom for the promise of security in false certainty.

This is to say, faced with a world too chaotic to understand, we long for form. Any configuration of that chaos into what we might call a fact, or a theory, or the story of what happened in a break-up is, in some sense, equally valid and equally invalid. Instead, we must reach for other criteria to judge its suitability: what is right, what is just, what is good, or what is, at least, good for us.

In 2022, reality collapses around us. Again, millions around the world attempt to manage the pain of the breakdown by throwing themselves behind false totalitarian gods. Others make the process of perception barely possible by reducing its field. We shut ourselves away, we dumb ourselves with substances, we put ourselves into black boxes and close our eyes so that we can reduce experience to just a beat.

And we listen to pop music. After a break-up, we attempt to configure an infinity of fragments and perceptions – an argument, how it felt when you fucked one time after a party, how you think he felt after you told him what you probably shouldn’t have told him – into some kind of narrative that makes sense, that gives us a hold on reality again. We turn to Ariana, to Joni, to Donna, and we realise that a song we’ve always known is about us in this very moment. Sometimes the fit between how we feel and what we perceive the song to be about is uncanny; sometimes it's a bit of a stretch (all songs about drugs can, with a bit of mental effort, really be about boys; all songs about boys can be about drugs). This is irrelevant. What matters is that none of our own attempts to bring order to the shit will really touch “reality”, either; our divas elevate our experience, turn our pain into something we can understand.

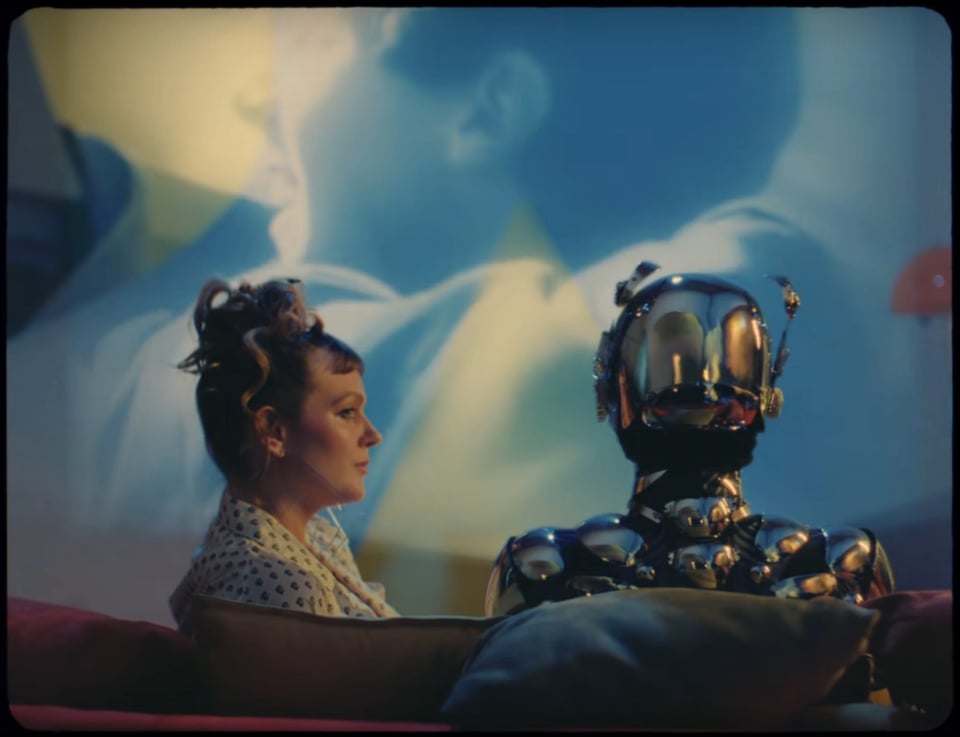

Tove Lo’s “No One Dies From Love” is both about, and a product of, this process of finding meaning in chaos. It’s proof that in 2022 it’s still possible to write a new heartbreak anthem. It’s also not only by some margin the greatest pop song of 2022, but also – like civilisation-ending cataclysms – the kind of pop-genius moment which only comes around once in a while, and not on a predictable schedule.

Each of my break-ups has its own anthem. I’ve cried more than once to Malou Prytz’s failed Eurovision pre-selection “I Do Me”; finding solace in flops, for fags, only adds to the delectable melodrama of the whole thing. With time my memories of the boy fade, but the song remains. To try to distinguish what “really” happened to how I live it through Malou would be futile.

We were so magical, why end this way?

I know you’re furious, yeah, just like me.

You got good reasons, but I do too.

“No One Dies From Love” revolves around three well-staked out positions: a “we”, a “you”, and an “I”. It turns almost methodically between the three of them, like one of those bell-ringing sequences which explores every possible combination of sounds, as much mathematics as music (We-I-You/I-You-Me/You-I-I/We-We-I[…]).

When love dies, something indistinguishable from magic comes to an end. When we’re in love, or think we are, the possibility of a “we”, a kind of shared perspective in which we escape the meat prisons of our selves and are able to somehow touch someone else, is entertained. In a real way, we put parts of ourselves into the other person (weeeey), entrusting them to serve as aspects of our beings, to do things for us we’re not yet or no longer able to do on our own; it seems, for a time, that we’re able to arrive at some kind of joined consciousness, or at least a dual perspective, where we can arrive at an agreement or a consensus if we talk the right way, if we raise our concerns the way our therapists advise us to, if we practice empathy and listen.

That falls apart in a break-up. Whoever said that “there are three versions of a story: my version, your version, and the truth” (I’m not looking it up; citation is internalised homophobia) had too much faith in the third version. Part of the pain of separation is the sudden, jolting onset of solipsism. We realise, abruptly and often uninvitedly, that I have my reasons, but you do too, I have my story and you have yours. Neither is the truth, and there’s no third party or objective record that can help us work out what really happened.

The pain, normally, is too much to process in rational ways. Melanie Klein, in her psychoanalytic work on infant development, reformulated Freud’s Oedipus complex from a developmental stage into a life-long alternation between two ways of dealing with the pain of separation. When faced with the first great separation (or second, after birth) – the realisation that third people exist, that the primary caregiver does not live and breathe purely to serve our needs – we deal with it in two ways. In the paranoid-schizoid position, we preserve our ideas of the possibility of pure good and evil, splitting ourselves and others into good or bad, finding (again) a false stability, even if it has the power to destroy us in the process; in the depressive position, we accept tonalities and sliding scales, that people can love us but also others, that we may not be as central in the universe as we imagined.

“No One Dies From Love” is very much a paranoid-schizoid banger. The reaction to the realisation of difference is fury. Even when the possibility of shared good intentions is contemplated (“I tried my best with you, you claim the same”), it cannot be held for long; as soon as it appears, it is pushed away, replaced with the desire to see the other suffering (“Don’t want you moving on, when it’s my end”). You hurt me, so you should suffer. I must be good, so you must have been bad. Otherwise, why would I feel like this.

Celine Dion, throughout her career, has allowed herself to become a kind of vector for civilisation’s grief and suffering in an act of supreme generosity. At the same time, she is absurd and glorious. Her music has got me through some of the hardest moments in my life. The funeral of René-Charles was staged not just as an imitation of a royal funeral, but as a genuine national event of mourning in Quebec, with visiting dignitaries, a televised ceremony, the body lying in state. Celine walks down the aisle, glamorous and tragic in black, to the sound of her own song, “Pour que tu m'aimes encore”. The camera swoops through the church in precise choreography. Celine kneels and kisses the coffin of the love of her life, a true, real love we all believe in. She stands up on the key change. The crowd rises to give her a standing ovation.

It escalated so fast.

We yelled things we can’t take back.

People will tell you all manner of crap to make sense of what someone said to you in an argument. Some examples:

What is said in the heat of the moment reflects what they really think

We say things in anger more to hurt the other, not to express how we feel

What angers us most in other people is when we see the parts of ourselves we hate in them

In vino veritas

And so on. I could go on, but I won’t, because none of this actually matters. When we say something in an argument, we have put it into the world, and we can’t take it back. We ourselves more often than not can’t make sense of whether we meant it or not, much less make such attributions on behalf of anyone else. The truth value of the statement is both irrelevant and impossible to define. It’s been said, and we have to process it.

The issue is the incoherence. We’ve built up an image of ourselves, of our beloved, of the “we”, and suddenly we hear or say something that contradicts the way we’ve found to make sense of things. This is, in the term of Leon Festinger, cognitive dissonance. When faced with information which contradicts a belief we hold dearly, we are faced with multiple courses of action to reduce the dissonance: disregard the importance or validity of the new information to hold on to our belief, adjust the belief – whether truly, or only superficially – to take into account the new information; only in rare cases abandon the belief altogether.

In the case of love, these courses of action don’t seem to apply. Love is, in a sense, unadjustable. We can convince ourselves we were never in love, but often the opposite is true: we end the relationship, but have to accept that the love remains. And if we stay, we can’t “dial down” the love we feel or receive. Instead, we have to accept the simultaneity of one thing that we believe – we are loved – and other, seemingly incompatible thing: we are also hated. This seems an impossible task. More on this later.

Anita Baker’s “Watch Your Step” is one of the great bitter kiss-off break-up anthems. I never noticed the glory of the opening line until now: “I know the kind of pain you offer. Baby, I’ve felt your kind of pain before.” The way you hurt me is horrible, but it’s also somewhat mundane, predictable. Tacky, even. Don’t think that what you’ve done to me is anything special. I’ve had boys like you before. Joe played it to close Panoramabar in August. I cried uncontrollably on the dancefloor for ten minutes. It was a moment. I think I’ve cried more in the past six months than the rest of my life combined.

Keep writing letters I’ll never send.

The Death of the Author is frequently misunderstood. In its undergraduate version, it’s an easy get-out-of-jail-free card for bad literary analysis: intention doesn’t matter, the text can mean what I want it to mean. But Barthes’s writing is full of wonder at the power of art to inspire meaning. Books, or paintings, or songs, are tapestries full of potential references and hyperlinks, connections sparked in the perception of its audience, rich archetypes and symbols which produce new meanings in different contexts. The greatest works of art (Velazquez’s Las Meninas; Edmund Spenser’s The Faerie Queene; Carly Rae Jepsen’s Fever) are staggering constructions, arrangements of signifiers so beautifully made that they achieve independence from creator and audience. They seem to have a kind of consciousness of their own, an ability to produce meaning without outside intervention.

I say this to introduce a question which I imagine will be at the centre of “No One Dies From Love” discourse for decades to come: is it significant that the line “I miss all the cool things we’d do/But what I miss the most is watching movies with you” appears in the video version of the song, but not in what we might imagine to be the “authoritative” release as single or album version? The answer is simple: of course it is. In a song this efficiently profound, any addition or omission alters the configuration of elements, changing the meaning of every other signifier in the process, like seeing someone who’s really good at Excel alter a single cell in a spreadsheet with conditional formatting and watching a cascade of colours and numbers change in an instant.

After the break, possibilities of recovery and reunion are entertained. We allow ourselves to imagine the pain of the other for an instant before pushing it away. Letters are written but unsent. Even the possibility of in some way living on in the other in the form of a happy memory seems impossible, “stained with blood”, repressed or obliterated. In this context, the admission that what is truly missed is not the “magic” of the first line, but a more mundane happy domesticity, is devastating. It’s one of the tentative attempts towards the depressive position which Lo puts forward before pulling away from. An acceptance that what was lost was not special for being magical but precisely for being real. Again, it’s too painful to bear. It’s retracted, becomes in its very omission a presence which hangs over the rest of the song. For the listener, it also provides a rare choice between two options: acknowledgement or denial.

In Lorde’s “Supercut”, from the first line we’re made aware that the singer is obsessing over not a relationship as such, but a compilation clip of its best and worst moments, the drama, the capital L Love of it. The song alternates between awareness of this fact, attempts at telling the story a different way, and plunging into that fantasy version. Maybe that lost affair was not the Taylor and Burton level of drama we imagine it to be, alone and drunk, dancing in our living room. But God, when she screams “we were wild and fluorescent, come home to my heart”, and it seems to come from the very depth of her being, it hits fucking hard.

No one dies from love. Guess I’ll be the first.

This year I invented a new genre or mode of pop: Gay Crisis Music. It’s very important to note that this is explicitly not crisis music for gays. It is music for Gay Crises. A Gay Crisis is fundamentally defined by the gap between the level of drama which a given situation deserves, and that which it provokes. For example, the boy you’ve been ignoring for months getting a boyfriend who is hotter than you is a Gay Crisis. Your ex-boyfriend getting a boyfriend who is hotter than you is just a normal crisis, for gays.

Gay Crisis Music functions through a very specific kind of camp. On listening, we’re aware that our situation does not merit the level of drama we are ascribing to it, but this can never be acknowledged explicitly. Case in point: Christine McVie’s “Ask Anybody” and Robyn’s “With Every Heartbeat” both contemplate the possibility of going back to a former love, and making everything better. But while Robyn comes to the conclusion that “we can keep trying but things will never change”, Christine holds fast to the belief that “Somehow, somewhere he’ll change/And we’ll try it all over again/Without all the pain”. Everybody says it won’t work, we know the idea of the painless reunion is absurd, but it’s never stated as such. That’s what makes “Ask Anybody” Gay Crisis Music: the ability to buy into a fantasy we know is preposterous, at least for 3-5 minutes.

In his Studies in Hysteria, Sigmund Freud famously defined the goal of psychoanalysis as “to relieve people of their neurotic unhappiness so that they can be normally unhappy”. The corollary and downside of this, of course, is that in becoming normally unhappy, to some extent we become normal, everyday, perhaps even a little gauche. We fall in love with our more extravagant suffering because it makes us feel special. Along with the pain of our depressions and anxieties and addictions often lies a sneaking suspicion that it might in some sense make us beautifully traumatised, unappreciated poets who just happen never to bother ever actually writing a fucking poem. Getting better is a kind of loss. Our identities as sufferers were also another configuration of form to make sense of the world. Normal unhappiness can mean a choice between accepting a more mundane configuration of our selves, or attempting to face life with a less solid sense of that self.

Take it to the chorus. Ten one-syllable words that you can’t believe nobody had put together in sequence before: “No one dies from love. Guess I’ll be the first.” This is perhaps the purest expression of Gay Crisis Music in the canon. I know that nobody dies from break-ups; and yet and yet and yet my pain is so real, I am so unique, that I will LITERALLY BE THE FIRST PERSON IN HISTORY to die from it. When I hear it I laugh from the audacity but I also feel it genuinely. There’s no nod or wink to acknowledge the absurdity of the claim; precisely its earnestness and full-bodied belief is what allows us to simultaneously relate to it and recognise its ridiculousness.

This, then, is the resolution which camp offers to the impossibility of making sense of love, of loss, of the world. Finding a middle ground is heteronormative nonsense and we shouldn’t accept it. Camp allows us to hold multiple, contradictory beliefs at the same time. We see Blanche DuBois, Sally Bowles, Hedda Gabler, Anna Delvey for the ridiculous, somewhat pathetic figures they “really” are. But we also completely buy into the fantasies they sell us, which they also “really” are. Like them, we want magic too. You have good reasons, but I do too. Your story is true, and mine is too. No one dies from love, I’ll die from love.

I think of all the obvious references I don’t make because I want to seem clever. Larkin’s “almost-instinct almost true: what will survive of us is love”, Auden witnessing the world descend into hell and concluding that “we must love one another or die”, Lana del Rey “serving up God in a burnt coffee pot” in church basement meetings. Why do we keep writing about love? Why do we write about anything else?

- Bleimann, December 2022

This is part one of a trilogy:

Chaos and Form (Dec 2022)

The Last Night and the Next Morning: Marlena, Marina, Ariana (Dec 2023)

Can You Feel It? (Dec 2024)

You can listen to a playlist of all songs mentioned across the three articles here.

Add a comment: