Eat This Newsletter 220: Mischief

Hello

Sometimes a big story seems to have been everywhere I look, and I wonder whether it is worth including here. So I ask people not quite as nerdy as me, and they say “what big story?”, which is why I do include it.

Lets Start With a Laugh

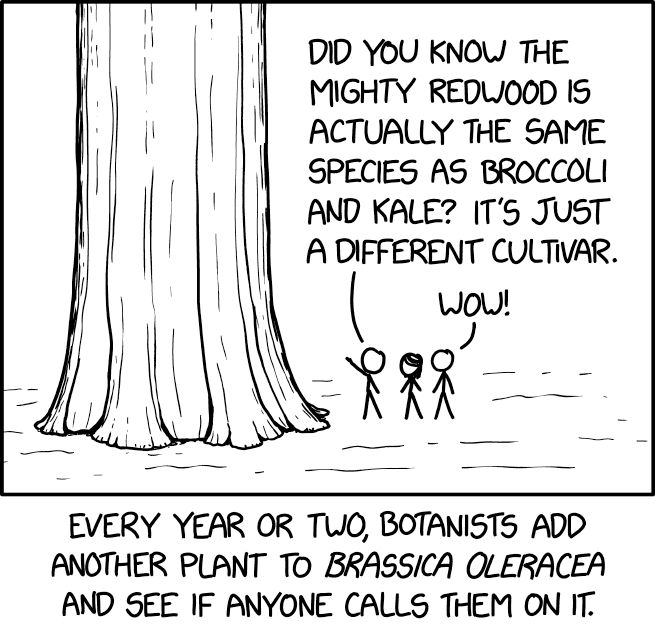

Randall Munroe is something of a cult figure for people who find him something of a cult figure, among whom I consider myself. According to a wiki that explains all his cartoons for those who don’t fully get them (among whom I occasionally consider myself), 4.88% of his output concerns food, but this the first time I’ve shared one here because … I found it LOL funny. (As are the wiki’s explanations, in an entirely different way.)

Not funny

Last week’s big story was in the Washington Post, detailing how Big Tobacco was, for a while, also Big Food, and during that time used the same marketing strategies to hook people on processed foods as on cigarettes.

The WaPo story reports on a study that set out to discover “whether hyper-palatable foods (HPF) were disproportionately developed in tobacco-owned food companies”. Indeed, they were. And in 2018, long after the tobacco companies had mostly sold off their food holdings, HPFs were widely available, “suggesting widespread saturation into the food system”.

The article offers a choice selection of jaw-droppers. My own favourite:

One Philip Morris executive joked about references that the healthiest item in a package of Lunchables was the napkin.

Ha ha.

The Price of Rice

Is in the news again, since India banned the export of all rice except basmati, briefly noted here back in July. Agence France Presses recently wrote about how this had resulted in a price that is a 15-year high, but still has a ways to go before it beats out the spike of 2008. The article sees this as a “preview of climate food disruption,” discussing the impact of the El Niño cycle we are currently entering. It does, however, quote experts to the effect that this current spike is not about running out of rice, it is about higher prices, although it does generously concede that “For some though, unaffordable prices amount to the same as a lack of supply: less food.”

Business as usual, then.

Rice by Any Other Name

Sometimes, I read an article and I marvel at the erudition it contains even when I cannot fully understand it. So it was with Deepa Reddy’s deep dive into Rice names & Memory work. She makes a strong case for the importance of names that describe Indian farmer varieties of rice and tell us more about them, but of course without any familiarity for the language much of the story was lost on me. One tidbit I picked up on: “Njavara with its potent medicinal value is ‘wild water grass,’ like the ‘Nivara’ of the old texts.” Oryza nivara is one of rice’s closest wild relatives. Is Njavara that wild relative, or a cultivar that resembles, or something else entirely?

The article contains a lot more in the intersection of agriculture, anthropology and ethnography and one bit that I hope to see explored further. The rice festival on which Deepa Reddy reported included a demonstration of the importance of memorisation to oral tradition, “by having a few young children recite, from top-to-bottom and entirely from memory, all the hundred-odd names of rices revived, conserved, and now grown in Tamil Nadu by local farmers”. She goes on to say:

Such memory practices and names do a lot more than just remind and entice; they help us understand the still vast array of heritage rices by telling us something about them, helping us to get to know them, remember them, choose between them, and by such methods safeguard them for all the time to come.

Yes, but what are the mnemonics that the children use? A memory palace for rice?

A Farewell to Rice (and other good things)

While children memorise the names of rice landraces in Tamil Nadu, old people (and youngsters) mourn the passing of an icon of Indian food in London. The India Club, on The Strand, has lost its fight against development, and Sean Wyer offers an obituary in his newsletter.

I share Sean Wyer’s sense that the India Club “was a rare thing in the area: a cross-section of London, where you really didn’t know who you’d be sitting across from on any given evening. It achieved this not just by being reasonably priced, but by being instantly lovable”. I can’t speak to the evenings, but that was certainly the case at lunchtimes on the many occasions when I fled from the canteen at work across the way to the joy of a perfect dosa.

While it is easy enough to comprehend what happened — the landlord wanted to sell and that was that — Sean Wyer gains some understanding through the eyes of a friend, who points out that “The odd thing about London is that it attributes very little value to the superfluous.” As Wyer concludes:

The argument that we are not able to make with enough force, as a collective of residents, is that the India Club is superfluous to our needs, but that we nonetheless want it. That its value lies beyond the mere function it serves.

That seems to me to be true of an awful lot of changes that we put up with in the name of someone else’s progress or efficiency.

“An Extravagant Desire of Doing Mischief”

Hogarth’s Gin Lane has indeed cropped up more times than I can remember in a variety of learned talks, but I had no idea that its appearance can result in a “gin lane klaxon” being “scurrilously sounded on social media”. That’s one of the tidbits in James Brown’s essay Liquid Bewitchment: Gin Drinking in England, 1700–1850 in The Public Domain Review. Indeed the article ought to call forth a chorus of gin land klaxons, because it is amply illustrated with several alternatives to Gin Lane that could be used to lend variety to any talk on alcohol. More than pictures, though, there is a good deal of information about gin, with only the barest nod to the agricultural surpluses that enabled its flourishing. It is to gin joints that we owe the bar of bars and the allure and glitter of the gin palace, and to George Cruikshank (Boz, in Dickens) that we owe some fine depictions of gin palaces. Cruikshank’s own history with the demon drink is also enlarged upon. Altogether fascinating.

Improving on Perfection

A perfectly ripe tomato vies with a perfectly ripe peach as the pinnacle of an ideal fruit. And yet, sometimes perfection is out of reach, and we must make do. To help, Modernist Cuisine offers its guide to Improving Pizza Sauce.

I’m still sniggering at the description of molecular gastronomy as ultra-processed foods for the rich, but let’s give them a fair shake.

In essence, the intricate interplay between sauce consistency, temperature, and pizza type highlights how sauces on pizzas go beyond conventional culinary roles, acting as essential elements in achieving diverse textures and flavors across various pizza styles.

Of course, as you read how to improve acidity, add umami, boost the tomato taste, sweeten or complement your sauce, you will need a deeper understanding of how exactly we perceive the taste of salt, which is surprisingly mysterious. There are, I learned, two different salt detectors. One signals yum, this is salty. The other signals yuck, this is too salty.

Returning, briefly, to that imperfect tomato, plant breeders have made a breakthrough. It is common knowledge that the past several decades of tomato breeding, at least for processing tomatoes, have been all about enhancing their ability to withstand rough, mechanised handling. Fresh tomatoes are mostly still picked by hand, and suffer because that is often done while they are unripe and so do not develop their full taste potential. Now, a team of researchers has announced in Nature Plants that they have isolated and characterised a gene called fs8.1, which toughens up mechanically-harvested tomatoes. This discovery, they say, “provides a potential route for introducing the beneficial allele into fresh-market tomatoes without reducing quality, thereby facilitating mechanical harvesting.”

Take care

Add a comment: