Eat This Newsletter 221: Linked

Hello

Every item in today’s issue seems to link up with at least one other thing, which I suppose reflects the reality of the food system.

Food Fight

Back in August, a Frenchman living in America, came to the following conclusion:

“Americans *genuinely* believe they have better food than in France. They really believe it. It’s truly extraordinary.

Given that he delivered himself of this aperçu on X-Twitter, it is not hard to imagine what happened next. “An online firestorm,” as Chris Arnade put it in his newsletter. The responses fell fairly neatly into, on the one side, Well, duh!, and, on the other Hop off! Arnade offers something a lot more thoughtful, agreeing with both sides on the way to concluding that indeed, America does not have a good food culture.

Yes, you can get a good version of almost any culture’s cuisine in America’s larger and more diverse cities. But no, the vast majority of Americans do not eat like that and set no great store by good food prepared from fresh ingredients.

Arnade fleshes the argument out with anecdotes of his own eating experiences around the world and with data. According to one poll, the French spend 2 hours 13 minutes eating and drinking each day to the Americans’ 1 hour 2 minutes.

If you’ve lived outside of the US you don’t need data to tell you Americans eat quickly, and mechanically. We gulp our food down like starving beasts intent on moving onto the next thing, while everyone else takes their time, savoring the experience.

The kicker, though, is that Arnade identifies the one American food culture that is central to some people’s identity, that they take their time over, that they might want to put on their tombstone: BBQ.

In all a fun, thought-provoking and interesting read. Also somewhat delicious is that I learned about this story, triggered by a fight that erupted on X-Twitter, from someone I follow on Mastodon, which I am liking more and more.

Eggs Tempered

A photograph of an egg shared recently shocked me with the lurid orange of its yolk, but I put it down to an overenthusiastic use of those “vividness” filters on photo-sharing sites. Turns out I was wrong: dayglo yolks are a definite thing.

I had long known about the feed supplements that egg farmers can use to tune the exact shade of yolk they supply, but had not appreciated the new lengths to which they are able to go. Marian Bull in Eater dives deep into those incandescent yolks to explain how they get to be that way and also what that says about the people who sell them and the people who buy them.

Come for the colours, stay for the historical survey of egg fashions and how hard-boiled may be about to have its moment.

Take One Mountain of Wasted Food …

… and view it through the lens of two different countries.

In the UK, we learn that the National Farmers’ Union successfully thwarted a government proposal to force large businesses to measure and publish the amount of food they waste. The NFU claimed that such a requirement would tie its members in additional red tape and might put their contracts at risk if the extent of waste were to become known. According to a report from Open Democracy, quite a few other trade associations and big food companies also lobbied against the proposals, but “the majority of large supermarket chains, food manufacturers and hospitality businesses supported mandatory reporting”.

According to Open Democracy, food waste costs the UK £19bn a year, but the government says that “any costs from measurement and reporting of it would be offset by only a 0.25% reduction in food waste”. If that is true, then mandatory reporting does seem a waste of time. Against that, the big farmers and retailers who support mandatory reporting argue that it does actually help them reduce waste and save money. Why isn’t that true for everybody involved in the supply of food?

In the US, Modern Farmer takes a look at the other end of food waste, the freegans who source their food from the piles of waste in dumpsters. The article points out that, as in the rest of life, dumpster diving may be much easier for white, middle class people than for others. People of colour are much more likely to suffer the attention of police and security staff as well as the effects of food shaming.

“When it comes to freeganism, the preconception that Blacks would dumpster dive out of necessity when Whites would do it out of concerns for the environment is the risk that many POCs will have to take if they venture into the freegan world.”

There are plenty of problems associated with this “last mile” of the food waste chain, and putting even a small part of it to good use to feed people is probably a worthwhile effort. There are other ways too. Pigs used to be the go-to system for recycling food waste into food, but the scale of modern pig rearing is strongly against that, and in the US 23 states forbid feeding garbage to pigs completely. On farms, bio-digesters can turn waste produce into methane, and some landfills encourage fermentation of agri-food waste and capture the resulting methane. Of course less food waste would be a good thing. However, I find myself wondering whether, like the focus on individual carbon footprints, the battle against individual food waste ought to be redirected upstream.

The Price of Everything

From Associated Press, a round-up of the usual suspects behind rising food prices. Floods and drought, dumb policy decisions, military aggression, all play their expected part, and AP’s crack global team of reporters bring us the local colour so essential to understanding the story.

One thing that AP story does not mention is supermarket prices. For the past few months there’s been a strong suspicion in many countries that food manufacturers and retailers have been creaming off extra profits through shrinkflation — a smaller package for the same price — and greedflation — putting up prices more than increased costs justify. Good data, though, are extremely hard to come by.

A couple of weeks ago I was fascinated to read a long thread by Mario Zechner, a software developer in Austria, in which he described his efforts to compile a historical database of comparative prices across Austrian supermarkets. The Austrian minister of labour and of digital and economic affairs had said it would take months to build such a database. Zechner got going in a couple of hours. And now Wired magazine offers some background to Zechner’s creation: This Website Exposes the Truth About Soaring Food Prices.

Actually, while it tells you, roughly, what Zechner did, and how his work is being put to work in other countries, Wired’s article does not in fact reveal the truths Zechner’s work exposed. For that, you should head to his thread and just keep scrolling. You do not need to join Mastodon to do so. It’s eye-opening, jaw-dropping and gob-smacking. One the surface, it looks like supermarkets collude on prices (or watch one another very closely). They manipulate their special offers to create a false “average” price. They charge customers in Austria more for the exact same product than their neighbours in Germany, even for products produced in Austria. There is clear evidence of shrinkflation. And so on and on. Astonishing.

Data, Good to Have

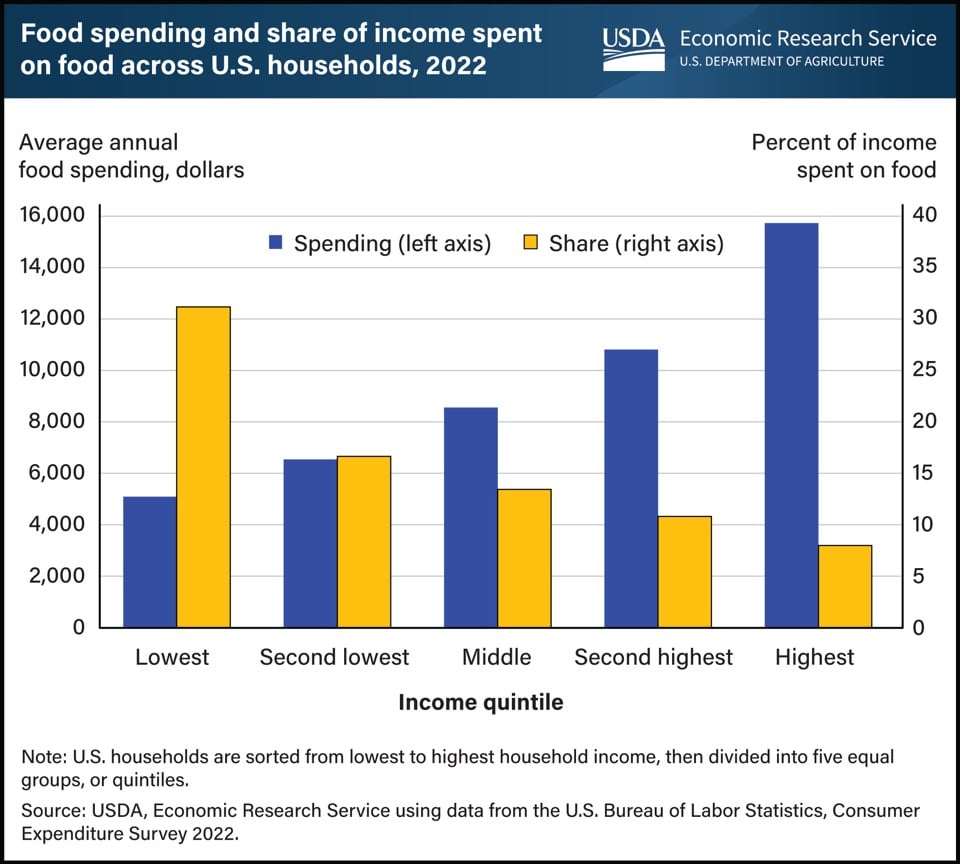

Here’s a turn-up for the books. According to no less an authority than the United States Department of Agriculture, poor people spend a greater proportion of household income on food.

And yet, despite — or perhaps because of — food prices increasing faster than overall inflation, food as a share of total expenditure decreased from 2019 to 2023 for the lower 60% of income. Is food cheaper? Did income rise? Or could it be that they couldn’t afford to buy as much food?

Milking It

Why are plant milks more expensive than cow milks? Mother Jones asks the tough questions. And the answer she comes up with is twofold. Big Dairy’s large volumes drive down the cost per litre. And also, Big Dairy’s lobbying power allows it to milk the US government of around $1 billion a year in direct subsidies, not bad for an investment of only $7 million a year in lobbying. Big Coffee also benefits from economies of scale which is why, the article says, in Europe Starbucks is slowly phasing out the price premium on non-dairy milks. I’d have thought that would be even easier in the US.

Take care

Add a comment: