Eat This Newsletter 228: Brave New Year

Hello

This first substantive issue for 2024 offers a couple of articles that I found thought-provoking because, of course, I had already thought along similar lines myself. There’s no avoiding my confirmation bias, which is why I am always interested to hear from you with things I might not otherwise consider.

Organic Food and Genetic Manipulation

Almost from the get-go, with the still-unrealised promise of cereals that would make their own nitrogenous fertiliser, proponents of genetically modified organisms (GMOs) have argued that they could also be good for organic farms. For all sorts of reasons, not all of them logical, most organic farmers and, more importantly, the regulators who define the meaning of “organic” have continued to shun any and all GMOs. A new article from Ambrook Research revisits the topic to ask Will the USDA Ever Allow GMOs on Organic Farms?, which we all know requires the answer “no”.

Like others before it, the article points out the strange fact that organic farmers are allowed to spray their crops with Bt toxin, derived from Bacillus thuringiensis bacteria, but are not allowed to plant crops engineered to make the toxin themselves using genes from the bacterium. It also mentions old favourites like GMO papaya, resistant to papaya ringspot virus, which saved the papaya industry on Hawaii, and other disease-resistant crops, also not permitted. Coming up to date, it usefully addresses the possibility of organic farmers making use of crops (and animals?) modified using CRISPR technology.

CRISPR is often referred to as gene editing, as opposed to engineering, because it can zero in on the organism’s own genes to make precise targeted changes, rather than physically bringing in foreign genes from a different species in a much more random process. (This is often called cisgenic technology as opposed to transgenic.) Proponents point out that this allows breeders to achieve the same results as they might with conventional methods in a fraction of the time. Mushrooms that turn brown much more slowly, for example, because scientists used CRISPR to disable one of the genes involved, could improve marketability and reduce waste. Because they involve no new DNA, the USDA has no interest in regulating them. Non-browning apples and potatoes have also been given a pass by the USDA, but no edited crops have been, yet, by the National Organic Standards Board.

The article offers several reasons for the refusal to countenance gene-edited crops, most of which seem to come down to potential confusion among organic customers, who must remain willing to pay the premium that organic growers say is essential. The Great Organic-Food Fraud did not apparently dent their trust in certification, but the need to distinguish genetic engineering from gene editing might?

In my opinion, one good reason for refusing gene editing as well as genetic engineering is that both are liable to reduce genetic diversity on farms and in seed supplies, which would be a greater threat to organic farmers than conventional.

Better Birds

A newsletter from a friend drew my attention to Oiling the Chicken Machine in The New Atlantis, which offers a strangely similar argument: “Queasy about lab-grown meat? Too bad — you’ve pretty much been eating it for decades.”

The point seems to be that the modern chicken owes everything to high-tech (conventional) breeding and concomitant research into feed, just as lab-grown meat is all about cells and feedstocks. The author writes:

A chicken breast cultured in a vat and one taken from a factory farm broiler are both products of the same miraculous, troubled system.

Extend this to reconstituted chicken nuggets in any shape you want, and the claim makes even more sense. The first half of the article is given over to the problems of both types of “product” and you might think that the point of the piece is to persuade people to give up on both existing industrial chicken meat and the promise of lab-grown meat. It isn’t. The second half tackles the crucial underlying premise of both production systems.

In its monomaniacal pursuit of efficiency, the conventional chicken industry has made ethical compromises that leave no ground on which to build an argument against lab-grown meat beyond whether it will be too expensive or make people sick. Any convincing ethical argument against lab-grown meat must therefore also make the case for something better than the status quo. It must explicitly claim that efficiency is not enough.

And that’s precisely what the author does.

p.s. I ought to note that the solution to the scourge of bird flu in chickens, which is keeping even free-range chickens indoors, might well be CRISPR. Given that practically all the meat chickens in the developed world are produced by three companies, there’s little risk that gene-edited birds will reduce chicken diversity in any meaningful way.

All Wet

It’s common enough knowledge that water is a problem for farming, especially in the American west, and equally that farming is a problem for water. Mother Jones magazine last month published a special investigation into America’s Water Woes. The five stories in the package offer a look at the many various ways in which water, agriculture and city dwellers interact. My favourite, perhaps because I had to do some research into it last year, is a brief recap of the strange story of water exports in the form of alfalfa hay, with links to more details.

Of Limited Interest I: online recipe magic

If you have ever looked for a recipe online, you may share the rage that many people, me included, feel when they find one of interest on the website of a food blogger. Get to the bleeding’ point, I scream as I scroll past endless pointless anecdotes, serving suggestions and dubious nutritional information on the way to the ingredients and method. Of course I know why all that guff is there. To force me to scroll past adverts, which may pay the blogger no matter how uninterested my eyeballs may be. Thanks to a post on Mastodon, I may soon be deprived of this particular source of online rage.

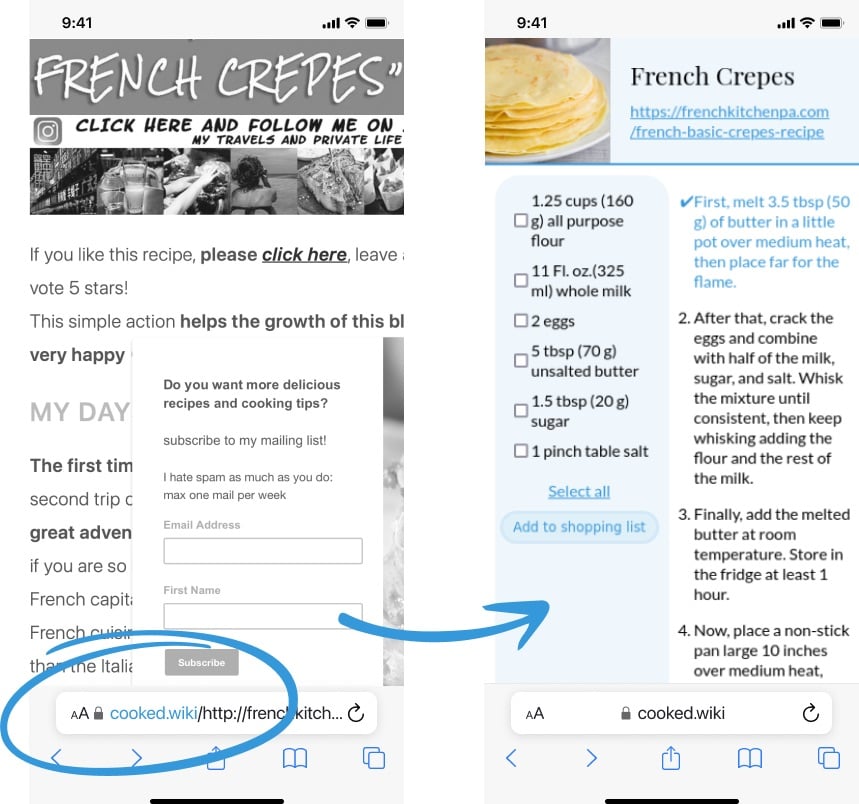

Your Smart Cookbook removes all the nonsense, leaving ingredients and method and an unassailable calm.

Simply add “cooked.wiki/” in front of the URL in your browser’s address bar when you’re browsing for a recipe.

This demo image from the site demonstrates the effect.

How exactly it manages to extract the good bits, like any sufficiently advanced technology, seems like magic. I confess, I have not yet had time to try it for myself, but I will, and the site offers all sorts of other benefits as well, especially if you subscribe. If you get to it before I do, please let me know what you think.

Of Limited Interest II: spicy etymology

Do you use asafoetida? Do you know what the word means? If you are a user, you will recognise the “foetid” part of the name. But asa? To the rescue comes Victor Mair of Language Log, with an extended piece on the satanically stinky spice. Don’t miss the comments, if this sort of thing interests you.

Take care

Add a comment: