the new is what you haven't noticed

Hope you all have been holding up, fighting the good fight, and finding peace where you can. As usual, I have some upcoming events and recommendations to share (always feel free to skip right to those), including an ask for handy people for an upcoming repair event, and a screening of my partner’s short film (!).

But first:

I can’t be alone in feeling the desire for a single, coherent train of thought. If you’ve read How to Do Nothing, you may remember the part where I list out 13 of the most recent things showing in my Twitter timeline, a mix of utter horrors, jokes, job postings, and other inanities. That chapter was called “Restoring the Grounds for Thought,” and it was about the concept, popularized by danah boyd, of context collapse — what happens to information when it’s stripped of context and jumbled together. In short, the result is a profane meaninglessness that can short-circuit our ability not only to think, but to do anything at all.

One of the biggest problems with this is how it feeds a cycle. Despair and confusion are uncomfortable feelings, so much so that I find myself trying to move away from them even before I realize what I’m doing. Unfortunately, one of the more readily available ways to scratch this itch is to go right back to the context-stripping machine. Run through this cycle a couple of times and you’re liable to feel low-level electrocuted.

To me this is about something bigger than attention spans and productivity. It is about what does and does not appear to us when we face each day in this electrocuted state. Two recent experiences brought this home to me. One was a hangout with a friend who barraged me with pronouncements of doom so unrelentingly that by the time we parted, hours later, I had barely said anything. While I understood the very real fear and demoralization, it was as though he was so distraught by the news that he was incapable of registering my presence.

The other was when, on the way in to a community space I hadn’t been to before, I was physically assaulted by a stranger who happened to be passing by. I probably should have gone home, but instead I brushed it off and continued on inside to a space filled with other strangers. Within the first conversation I had, unaware of how constricted my entire being still was, I made an unusual amount of snap judgements about the person — almost completely writing them off, unable to actually listen or ask real questions. What’s more, none of this reaction was clear to me until several visits later when I talked to them again. I actually could not believe that that first perception and the one I was having now were of the same person.

In their own ways, these experiences made me think about the relationship between fear and attention. When we voluntarily place ourselves in environments of bombardment and context collapse, administering shocks to ourselves over and over again all day, we are not just making it harder to focus. We are dragging our souls through the mud. A fearful mind has a narrow, impoverished lens on the world. Others become less real. We become less real. Whole pathways of thought and action fail to materialize.

This is the opposite of what we need right now. As a friend recently put it to me, we need everyone’s A game. And what does an A game require? It requires practice, maintenance. I’ve been thinking of something I read a long time ago, in Chogyam Trungpa’s book Mindfulness in Action:

The outbreath is like a whetstone, and the mind is like the knife or sword that is being sharpened on that stone. When you sharpen a knife, you draw the blade of the knife across the sharpening stone. Following your outbreath is like drawing the blade of mind across the breath.

—

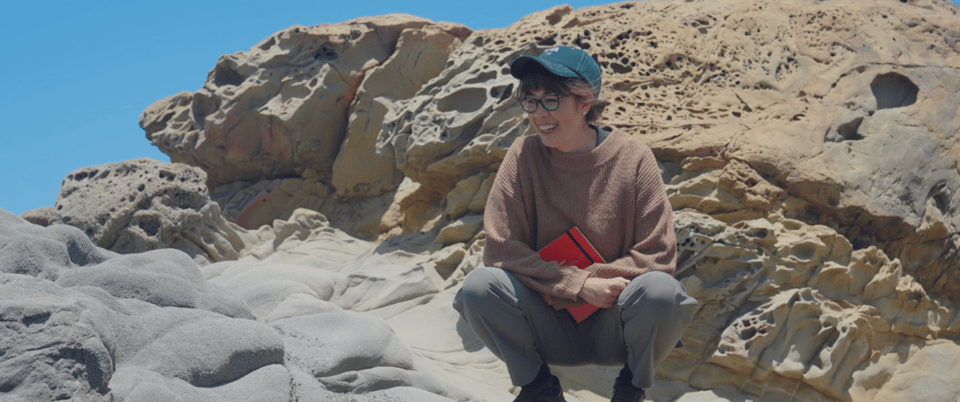

Last week I stood in a really long line to get my COVID shot. I was thinking about how often we are the ones interrupting ourselves, cutting short our own trains of thought, shocking ourselves. I decided to leave my phone in my backpack. Instead I talked to the person behind me for a while, and then just looked around. It was a pretty standard hospital environment, with seemingly not much to see. But I still had 15 minutes left. The phone burned in my backpack. I decided to look for things that were blue. As the line inched along, I saw blue scrubs, blue biowaste containers, a blue chair, a middle-aged woman with ethereally blue hair, the blue sky outside the window. More and more blue things appeared, until this very same space that had seemed empty now seemed full. By the time I reached the front of the line, I was next to an abstract painting with large rectangular strokes of dull colors, in the center of which sat a tiny remainder of an excruciatingly pure blue.

I remembered an old project I’d done that involved something similar. When I was 20, I went on a long trip to Greece with a friend who had family there, and could only take a finite number of photos on my digital camera because I didn’t have another memory card. Because of the photos’ scarcity, the set of them quickly became personally canonical, constituting or even replacing the only memories I had of the trip.

Years later, in my visual art projects, I’d become interested in everything a photo captures “accidentally.” I went back to some of those old photos and, as an experiment, pulled out everything green.

The main effect that this experiment had was to destabilize the images and their long-hardened meanings, proving to me that just because I’d been there and taken the photo didn’t mean I’d registered everything in the visual field. It demonstrated that “new” wasn’t always somewhere else; sometimes it was inside the very thing I was looking at. It was also an exercise in moving my attention, a reminder that the decision was open to me at all.

If there is one thing that I want to leave you with, it’s with a reminder that that decision is open to you too. Many well-funded and well-designed forces may be arrayed against this ability to move attention, and using it may require constant practice and maintenance against those forces, but it remains available for even the most despair- and anxiety-addled mind. Getting it back just takes time.

Moreover, if the opposite of context collapse is “context collection,” then we’re faced with the task of collecting, piecing back together a continuity that is now shattered by default.

Here are a few things that have lately helped me to find more continuity, from big to small:

• There is a concept in horseback riding of “soft eyes,” which is supposed to mimic how the horse sees: instead of focusing in intensely on one thing in your field of vision, you try to have a full awareness of your peripheral vision. I find this to be is a useful practice both literally and figuratively. When you look at individual things or take in information, try to broaden out in time and / or space — mostly by resisting the urge to over-focus.

• The person who runs my native plant restoration group told me about a practice where you every time you encounter something beautiful, you take 10 breaths to appreciate it. I think this can be expanded beyond what is beautiful to what is meaningful, even that which feels unbearable. When you encounter something painful, resist the urge to immediately distract yourself with something unrelated. Sit with it, give it its due; let it mean something more than the fight-or-flight chemicals that propel you on to the next thing, the next horror.

• If you’re able and have the time: Work on something good with other people — in person, regularly, for several hours at a time.

• More prosaically, I think sometimes we seek information and stimulus because we actually just need a break from whatever we’re doing or seeing. Try taking a break that doesn’t hijack your train of thought. Sometimes I just sit and close my eyes for a minute.

• I know everyone says this, but meditating for even 10 minutes in the morning is incredibly helpful. I live somewhere where it can be too loud to do this without headphones, so I’ll sometimes make recourse to videos of a local dawn chorus.

• Life is full of moments where you’re waiting for something for 5 or 10 minutes. Challenge yourself not to look at your phone in that time — don’t think of it as a once and for all, cold turkey thing. Just try it and see what happens. (Incidentally, I have had great conversations with strangers because of this.)

• In the realm of music: I’m surprised at how much of a difference it makes to listen to full albums instead of playlists. And if you use a service that autoplays “similar” stuff at the end of the album, turn that off.

And now to some news:

• At my friends’ new space in Oakland, Local Economy, I will be helping to run a repair event on the afternoon of December 6. Inspired by the Fixit Clinics I’ve been attending, the idea is that people can bring in their broken stuff and get some advice on what’s wrong with it and how to fix it. I’m looking for folks who know how to repair clothes and especially appliances — you don’t have to be an expert in anything specific, as I realize that there are many people who are just generally handy. If you’ve had experience with these types of events, that’s even better. Please respond to this email if this describes you and you’re in the East Bay / willing to come here!

• Next week is the Drunken Film Fest in Oakland 🫨 The short film my partner wrote will be in the 7pm screening on October 7 at Beeryland! It’s a horror-comedy set entirely in a 90s TV Guide Channel. I will try not to yell out all my favorite jokes.

• At 7pm on October 20, I’ll be doing an event with Cory Doctorow for his forthcoming book, Enshittification: Why Everything Suddenly Got Worse and What to Do About It. I can tell you now that this book is a wild ride.

• I’ll be in conversation about my books at The Forum at Grace Cathedral on Sunday November 2, at 9:30am (sorry).

Lastly, some (admittedly discontinuous) recommendations:

• My friend Brandon Tauszik made a really incredible short documentary called “A City Fights Back: How LA Defends Itself From ICE.” It’s such important reporting; please watch it.

• Everyone should go see One Battle After Another.

• If you’re in the Bay Area, Chris Chen’s play, The Motion, is at Shotgun Players until October 12. It’s unlike any play I’ve ever seen. I was in residence with Chris when he was developing the play, and was already floored by a table read of it then, but the set and the sound design really make it a masterpiece.

• This article about ChatGPT ruining marriages was an insane read.

• In Enshittification, I learned about a search engine called Kagi. Using it reminds me of a time when Google’s search just worked, felt straightforward, and wasn’t rife with ads and AI summaries. (My hatred of AI summaries is a topic for another newsletter.)

Until next time: Keep looking out, breathing, and sharpening that knife of the mind.

Yours,

Jenny