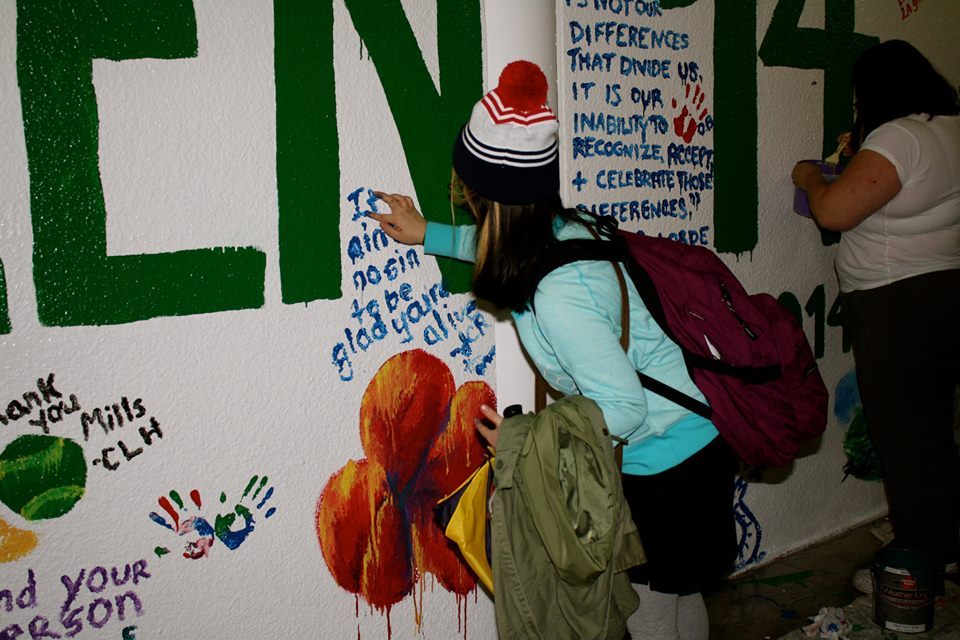

it ain't no sin to be glad you're alive

content warning: C-PTSD, suicide

I was about 14 when I stole my dad’s Bruce Springsteen greatest hits CD. It wasn’t my first introduction to Springsteen — my parents spent nearly a decade in New Jersey after immigrating to the States, so I was raised on his music, just as any good pseudo-New Jerseyan from the Southwest would. Being raised on it isn’t the same as seeking it out myself. I had only just started checking out more rock music on my own.

That was also not long after my first brush with trauma, something that left me depressed and suicidal when it happened. Hitting play on “Thunder Road” gave me life that I didn’t realize that I needed. It kept the suicidal thoughts at bay. I did the biggest deep dive into Springsteen’s music and going to his concerts was all I wanted for both my 16th birthday and high school graduation gift.

I haven’t lived an adult life without knowing trauma. It creeps up on you when you’re not prepared for it, and even when you are, it shapeshifts. Emotions aren’t easy to manage when you’re neurodivergent, either.

When I would have thoughts of feeling suicidal in college, I would have friends text me, “Listen to Bruce,” so I did. I didn’t realize then that it was the healthiest coping mechanism I had at my disposal, but I didn’t utilize it until into my mid-20s.

It’s one thing to be able to keep suicidal thoughts away for a long time. It’s doable, but tough. When you go through so much trauma that makes you lose any faith in living, fearing that it will happen to you again — and again, and again, and again — you wonder what any point of it is at all.

I thought I had been holding up well. I thought I was doing what I needed to to get by — because for me, I know the most I can do is tolerate living; I wasn’t seeking more than tolerance — until I wasn’t.

I had a rush of 10 year trauma markers happen. One by one, I couldn’t escape the pain of what happened to me. I was flooded with emotions I didn’t want, memories I wish I never held. I retreated from society. It was easy to hide that I wasn’t okay. It was easy to hide I was seriously contemplating suicide again.

That was, until it crept up in a way I couldn’t avoid it.

I went back into intensive treatment. I got on a different treatment plan. I tried different things so I could keep my mind as occupied as it could be.

I got the reminders again: “Listen to Bruce.” The more you get older, the more things change, the more they stay the same.

I just wanted to get back to a baseline of tolerating living with this trauma I never asked for or wanted, knowing I will never be completely rid of it. How the peaks and valleys were stark, and the lows were lower than you ever wanted to feel. I couldn’t avoid it; I could only go through it, and that meant feeling all the pain it comes with.

I had tickets to see Springsteen in Phoenix, something I was reminded of regularly by the Ticketmaster app, despite it asking me “Can’t make the show? You can always relist it!” Like hell I was going to.

I knew I needed that show and it was going to be good for me, and it was. But in the month leading up to the show, I didn’t realize that I was also going to decide to go to the Las Vegas or Los Angeles shows, let alone choosing to go to a San Francisco show five hours before the band hit the stage.

2:45 to 3:15 hours of nonstop energy, reminding me of what being alive felt like. I was chasing feeling my level of normal again — in a way, similar to how I did when I was 14, only this time, I had a car and an income that allowed me to go to shows in three different states.

Living was never going to be painless for me. But in those four evenings I spent with tens of thousands who were also seeking the magic of a Springsteen show, he called out, “It ain’t no sin to be glad you’re alive.” “Glad,” personally, may feel like a stretch, but I was there, alive.