… or, Mortal Decay

A strange thing happened this week, which is that I realized the book, if a book it be, I thought I’d started is in fact a different book. This came about when I observed that so many of my examples from the fragmentary passage I’ve shared, over the past couple weeks, on “how things acquire meaning,” come from the domain of taste. But this is not new — the first two examples, sriracha and broccoli, come from something I dashed off ten or eleven months ago, by way of preface to an experiment I’d had lying in the proverbial drawer since 2019 and which was now, improbably, to appear in a singular and largely forgotten journal known as Res. The third example from the Res preface concerned the furniture of George Nakashima, and this too is apposite, for it turns out the theme I thought I’d set aside but which has been lying in wait is patina. So today I’m going to offer a new opening, one that frames the three numbered sections from the past two editions as the way into an investigation of patina, plus a new section. At length this will knit up with markmaking, though how, precisely, remains to be seen.

But first! It’s been a desultory week for markmaking. It’s not that I’ve neglected it, it’s just that, since last week, when we had the dog, I’ve found myself unable to return to things that hold still, or at least, plants. A lot of what I’ve been doing with the Zebra G this week has come down to experiments in technique — refining my control of line variation, learning (rather, failing) to render assorted shapes and textures faithfully, understanding the limits of the G, not to say pigment-based ink more generally. Chiefly these come down to limited possibilities for conveying translucency, the layered occlusion of materials that admit some light but not all, etc. Of course it’s eminently possible to dilute pigment ink and use it diluted on the nib, and this I’ve done with the other ink you’ve seen me using here, from Kakimori. But somehow, over the past month, since I started working with the Dominant Industry ink, I’ve got out of the habit of setting out a glass of lukewarm water when I work — maybe it’s just seemed like too much fuss, or maybe I’ve simply wanted to minimize the number of things that, in my clumsiness, I might knock over.

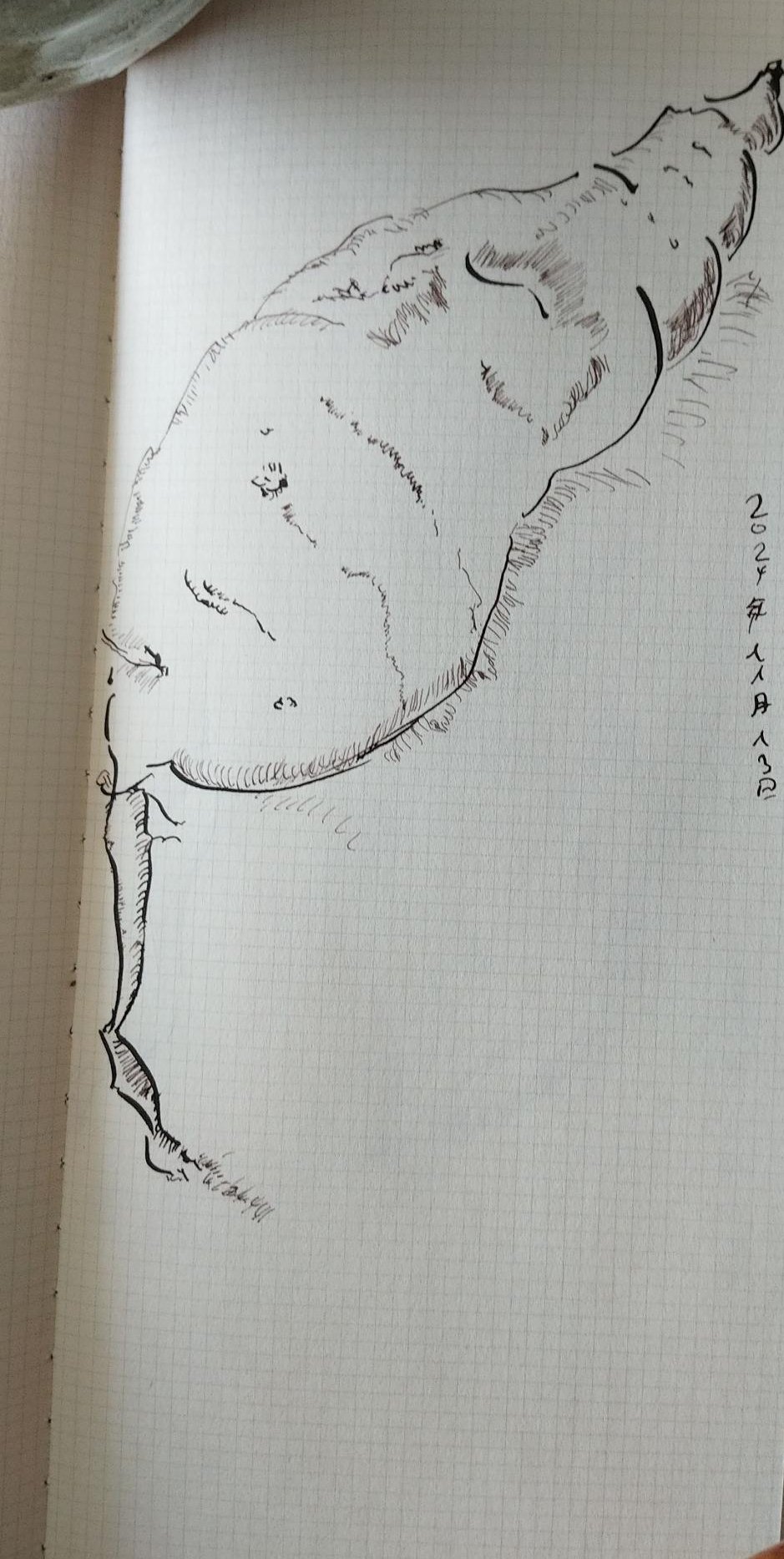

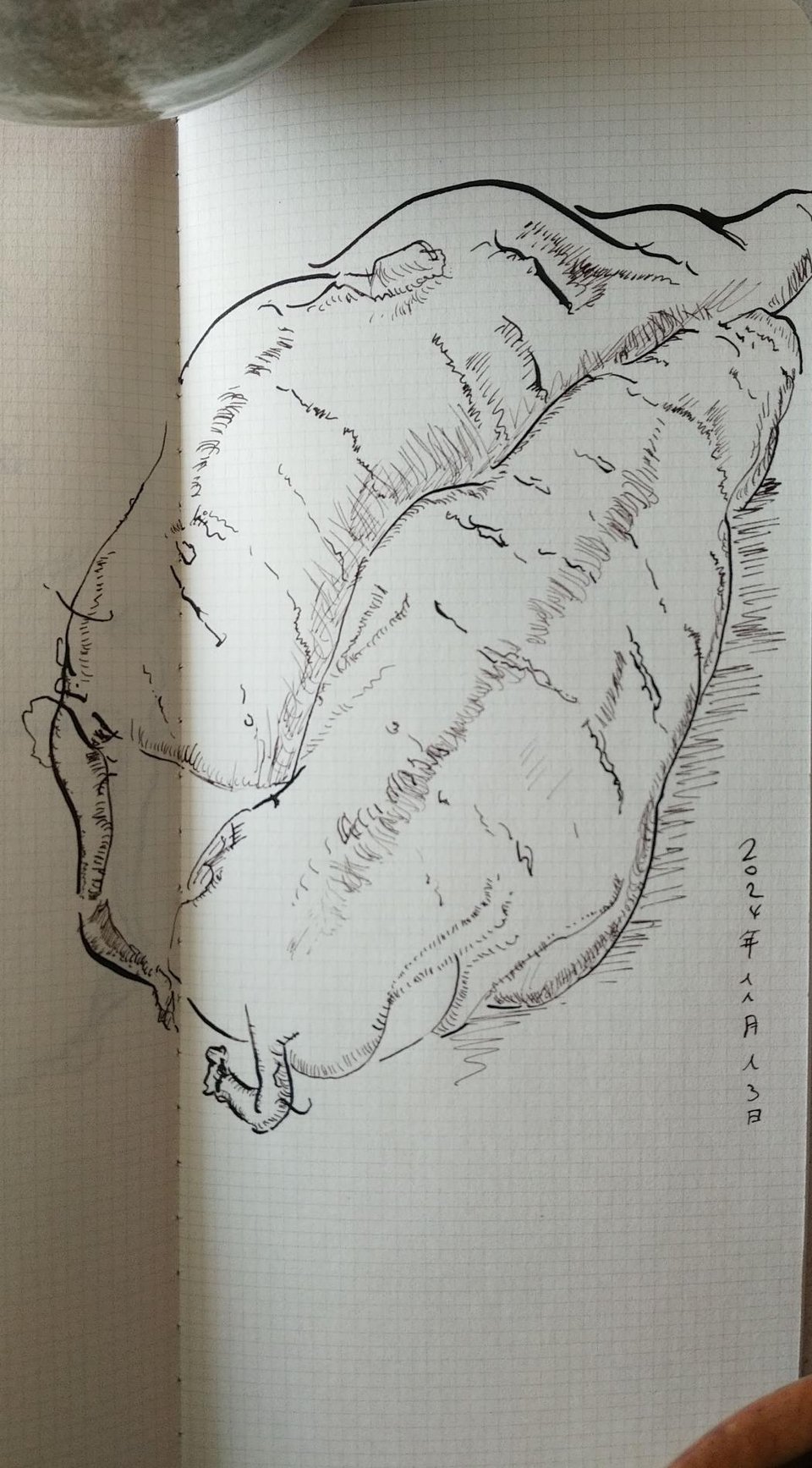

The upshot of all this is that I have fewer drawings to share this week, and what I have is not terribly interesting. But here you go.

It’s amazing how many ways there are to go wrong with something as simple as a tuber — just getting the proportions right, though you’d think, how hard could it be? Compared, say, to a deliquescent plant where you have no hope of faithfully reproducing the relationships among the different branches. On the second one, the pair, I suspect I should’ve stopped sooner — the first one leaves more for the viewer to fill in.

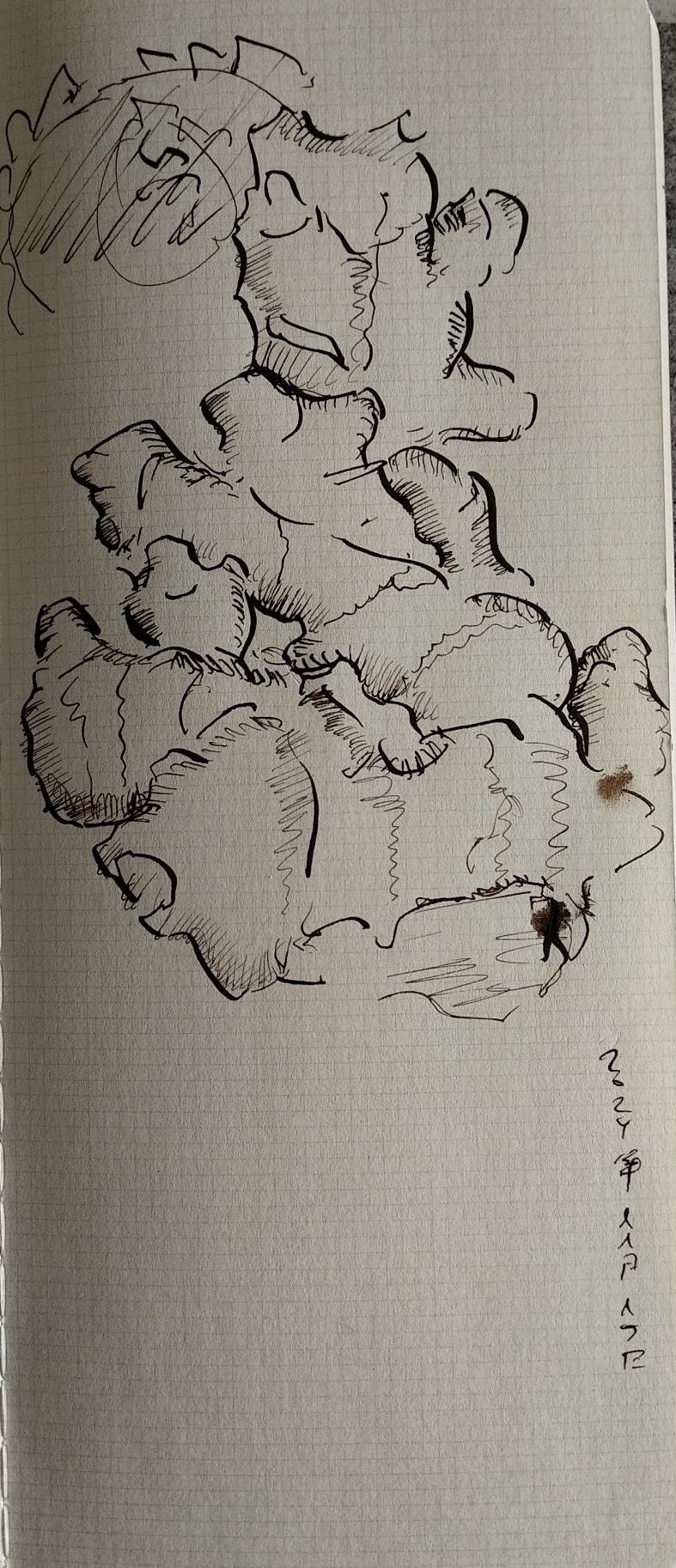

Ginger continues to foil me, though here, finally, I managed to render something identifiably ginger-like. The squiggle in the background is intended to evoke the foliate pattern of the surface of the bowl — this is the same bowl you’ve seen in the pomegranate drawings — but apparently I’d given up by the time I got to that.

Be well — and as ever, if this made your week fractionally less oppressive, by all means share it and encourage others to tap the proverbial “Subscribe.”

TASTE

1

This cup, with its chipped lip where someone once knocked it against the sink, rinsing it out—I look at it and know it has meaning for me, but what gives it its meaning? In fact, what gives any thing its meaning? How do things acquire meaning—and what roles does wear (the chip, the tear, the abrasion, the stain) play? But let us start small: how do words acquire meaning? Consider, say, the word sriracha.

2

Have I ever tasted sriracha? Likely but uncertain. I have but a vague sense of what sriracha tastes like, and no comparative basis, no sense of what it should taste like of the sort that can only be informed by extensive experience, discussion, etc. Sriracha lies beyond the compass of my experience, or, at best, it occupies a penumbral zone between that which I know by experience and that which I know from others’ accounts. And yet there is no question that the word sriracha has meaning for me.

3

Contrast broccoli. Here there is no question: I have had ample experience with broccoli, enough, in fact, to last a lifetime, and while I can imagine knowing a vegetable by description, having never tasted it, my history with broccoli seems to inform the meaning that the word broccoli has for me.

A better contrast: tamari, or genmaisu, or—a penumbral case—nattō. Perhaps there is something distinctive about the experience of condiments—distinctive even within the comparatively compact remit of gustatory experience. (Would it be less meaningful to contrast, say, my knowledge of sriracha to my knowledge of wearing clothes?)

4

Switching modalities, and freeing ourselves of the aura of the dictionary word: how does the syntagm the pencil-like feedback of a Sailor fountain pen acquire meaning? No question, the phrase had meaning for me long before I picked up a Sailor fountain pen, and perhaps the key is the pencil-like, which offers a bridge to more familiar experiences. But the phrase became more meaningful to me once I’d become familiar with Sailor fountain pens.

(Does it matter how we hear the question? —acquire meaning for the individual versus acquire meaning for the community? It is possible that the meaning of the phrase the pencil-like feedback of a Sailor fountain pen has for me diverges from that which it has for most members of the fountain pen community—in fact, I suspect this is the case. For most of the discussion about the distinctive feel of Sailors is concerned with contemporary Sailors, whereas the two I use were made in 1967 and sometime between 1970 and 1973. So while there’s definitely something in the feel of my old Sailors that corresponds, in my mind, to pencil-like—some combination of how the nib is ground, with an edge along the sagittal midline, and the dryness of the feed—it’s possible I’ve projected the qualifier pencil-like on some other sensation than what most people have in mind when they refer to the pencil-like feedback of a Sailor fountain pen.)

You just read issue #41 of Stuff. You can also browse the full archives of this newsletter.