The Weekly, June 10, 2024

Hi all,

I hope you’ll read Tara Burton’s piece on Narnia linked below. She gets at something really important that is both utterly central for Tolkien and Lewis and broadly forgotten today:

As in Tolkien, where it is precisely the goodness and smallness and sweetness and vulnerability of the hobbits’ Shire that demands protection, in Lewis, what matters in life and national epic alike is not the grand sweeping narrative but the little stories of the little people (and animals) who just want to make their way comfortably in the world, and with one another. Those few characters—The Magician’s Nephew’s Jadis or Uncle Andrew, say, or the wicked scientist Weston in Out of the Silent Planet—who claim a higher power, a deeper privilege, or a wider panorama, are not merely wicked but demonic, corrupting not just themselves but the worlds into which they enter; inevitably, it is precisely their refusal to see themselves as ordinary, embedded in the communal ordinariness of their world, that reveals to the reader that they are not to be trusted.

Against such a background, Lewis’s parochialism becomes not a defect of his work but one of his virtues. If England’s national character is to be preserved, alongside her folk ways and folk wisdom, it is not because she has been an Empire but because she remembers (or, at least, Lewis quixotically hopes she remembers) what it means to be a village. Nobody, in Narnia, fights for glory, or for grandeur, or for Greatness. They fight for Narnia—and they fight for each other. They fight so that they can go home and sleep in warm beds and eat food far more wholesome than any boarding school will ever serve.

The challenge we have now, I think, is that the two most common attitudes toward place in American life today are either an utter indifference to it or a blood and soil-style commitment to it.

The unique genius of America, I think, is that at our best we’ve found ways of copying this British love of the village in our own contexts, but across many different cultures and ethnicities. It’s something like this: Place, yes. Blood and soil, no.

I am thinking now of my Swedish ancestors settling into life in Oakland, NE, one of three Nebraska towns claiming to be “the Swedish capital of Nebraska,” and I am also thinking of my Greek ancestors first settling in Boston and making a life for themselves there before coming to Nebraska and finding some small and surprising bits of Greece in our old prairie town. And I’m also thinking of the working class railroad town of Havelock that my Swedish grandfather and Greek grandmother made their own after their marriage.

When the town was first being built in the 1890s and 1900s, it looked something like this:

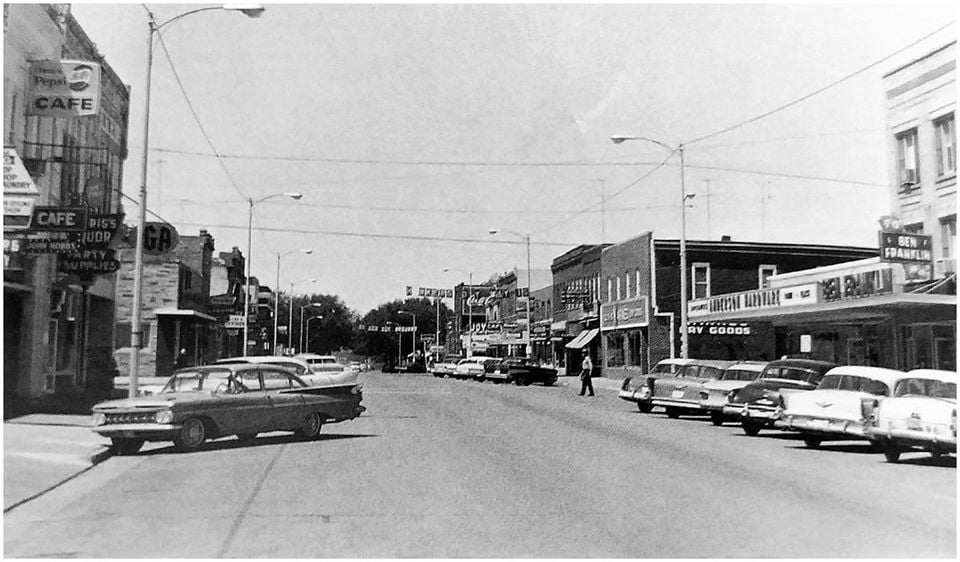

By the time my grandparents moved there after grandpa got back from World War II, it would’ve looked closer to this, though I’m guessing this photo is from the late 50s or 60s rather than the late 40s when they came:

Note that the first photo is taken looking east with the north side of the main drag being on the left side of the photo whereas this photo is taken facing west, which places the north side of the street on the right. If you look almost dead center you can see the word “joy” just beneath the Coca Cola billboard. That’s the Joyo Theatre, an old neighborhood staple. And here’s Havelock today—the Joyo’s still there.

The genius of Lewis and Tolkien is that they give us ways in their writing to love our own villages without becoming closed, mistrustful, bigoted, and narrow. They give us ways of loving the small without making ourselves small. They knew that the things we love in our small places are themselves echoes of something universal—the inside is larger than the outside, as Lewis memorably says in The Last Battle.

So how do we have good localism without it curdling into something vicious and narrow in the wrong sense? We can find some help by borrowing a bit first from Wallace Stegner and then borrowing another from Johannes Althusius. Each will give us a key distinction to use in defining what we’re after.

First, from Stegner: The localist democratic impulse in American life works best when mediated through what Stegner called “stickers” rather than boomers. Stegner’s student Wendell Berry explained the difference in his “It All Turns on Affection” Jefferson Lecture given to the National Endowment for the Humanities in 2012:

My effort to make sense of this memory and its encompassing history has depended on a pair of terms used by my teacher, Wallace Stegner. He thought rightly that we Americans, by inclination at least, have been divided into two kinds: “boomers” and “stickers.” Boomers, he said, are “those who pillage and run,” who want “to make a killing and end up on Easy Street,” whereas stickers are “those who settle, and love the life they have made and the place they have made it in.”2 “Boomer” names a kind of person and a kind of ambition that is the major theme, so far, of the history of the European races in our country. “Sticker” names a kind of person and also a desire that is, so far, a minor theme of that history, but a theme persistent enough to remain significant and to offer, still, a significant hope.

The boomer is motivated by greed, the desire for money, property, and therefore power. James B. Duke was a boomer, if we can extend the definition to include pillage in absentia. He went, or sent, wherever the getting was good, and he got as much as he could take.

Stickers on the contrary are motivated by affection, by such love for a place and its life that they want to preserve it and remain in it. Of my grandfather I need to say only that he shared in the virtues and the faults of his kind and time, one of his virtues being that he was a sticker. He belonged to a family who had come to Kentucky from Virginia, and who intended to go no farther. He was the third in his paternal line to live in the neighborhood of our little town of Port Royal, and he was the second to own the farm where he was born in 1864 and where he died in 1946.

Stickers make for good democrats because they belong to a place and don’t seek its prosperity at the expense of others or at the expense of its own health and coherence. Boomers make for lousy democrats because their primary way of relating to place and neighbor is from an assumed competition. Taken to its most extreme it looks something like Daniel Plainview in There Will Be Blood:

Stegner gives us a way to understand how to love one place without hating others or viewing neighbors as rivals or enemies.

The other idea we need comes from Althusius. In the opening pages of his Politica Althusius argues that the purpose of politics is to make the unavoidable, necessary social relationships that all humans must share mutually delightful and edifying. This is a far way removed from the more Schmittian imagination of politics you get from the dissident right in which all that matters is who/whom: “The whole question is—who will overtake whom?” If politics is chiefly about who overtakes whom, then we love our own places best by fearing and resenting others, recognizing them as a threat to us that must be held in abeyance, at best.

Such an imagination will also hardwire a certain obsession with power into your politics (to the exclusion of morality) as well as a disdain for weakness—you can’t harbor the weak in your place because they will hinder you in your attempt to protect yourself. Note the disdainful way this dissident right blogger, who is associated with Raw Egg Nationalist, Costin Almariu (Bronze Age Pervert), and Jonathan Keeperman (L0m3z) talks about the weak:

Is there anything more tiresome than morality in politics?

— eugyppius (@eugyppius1) June 7, 2024

We have had enough of this hypermoralism, on the left and the notional ‚right‘, to last a millennium.

I despise above all those who ask me to care about weakness, whatever its form. I want an amoral politics and an…

The challenge facing us now, it seems to me, is that we have lost our sense of rootedness and belonging within specific places and communities. Yet people desperately need roots and communal bonds to give them a sense of purpose, meaning, and identity as they navigate through life. We’ve lived through a time of uprooting. And what we have now is a desperate need to be re-rooted. Yet because of how estranged we have become from each other, it is hard for us to take up the task of being rooted again in a way that is governed and constrained by morals rather than an utterly amoral search for belonging that regards anyone outside one’s chosen tribe as an enemy. What I have taken from figures like Tolkien and Lewis and Berry and Stegner and Althusius is a way of loving real places and real communities without diminishing ourselves through hatred of neighbors, assumed superiorities, or a power-mad political doctrine.

Books

I finished Jeanne Murray Walker’s recent memoir. It was of interest to me not only because it was an ex-fundamentalist book, but because Walker grew up in Lincoln and her family helped found the basically fundamentalist Christian school I attended for two fairly miserable years. I also recognized the church she grew up attending. It’s a kinder book than most ex-fundamentalist texts and a more mature one as well. If you are interested in such books, I’d recommend it. (We’ll be running a review later this week by Miles Smith of some other exvangelical memoirs.)

Alongside the Walker, I am also dipping into Rowan Williams’s Being Christian and Emil Brunner’s Our Faith as I try to draft my badly overdue book for IVP.

I’m also working through Nadya Williams’s Cultural Christians in the Early Church and started Haidt’s new Anxious Generation.

Articles

Tara Burton on Narnia

Mia Staub on therapy speak

Jessica Lewis on the teens befriending AI chat bots

Alejandro Teran-Somohano on Tolkien and the machine

Beth McMurtrie on the end of reading

Elsewhere

I’ve never done any kind of woodworking, but this video kind of makes me want to try:

Thanks for reading!

Under the Mercy,

~Jake