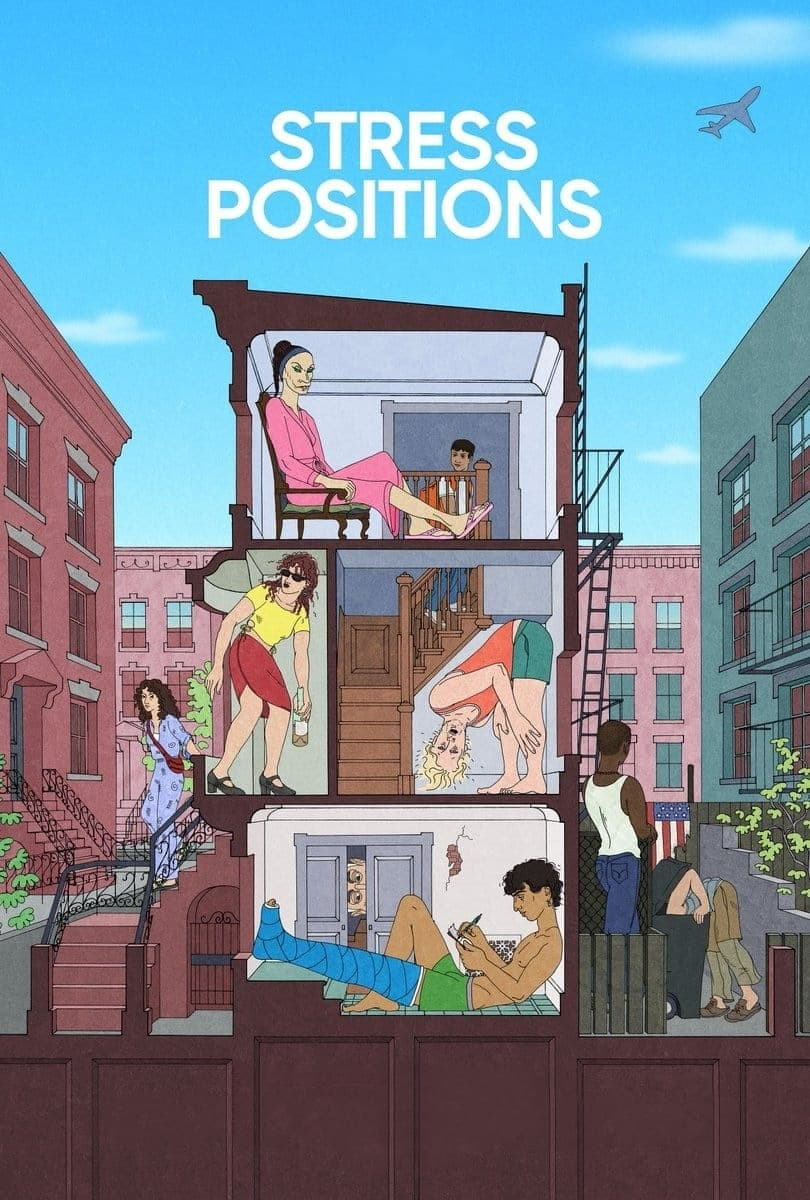

Stress Positions

I’ve been going to the movies a lot lately, in the last week I’ve seen Theda Hammel’s “Stress Positions” and Jane Schoenbrun’s “I Saw the TV Glow.”

I also re-watched Rohmer’s Tale of Winter and this time through noticed Loïc’s line, something like, “you see the spiritual in everything except Christianity,” and the fact that his prayer, for better or worse, succeeds. How did I miss it. Amazing that the same guy who made these wonderful tales of the seasons could have made such evil cynical films as La Collectionneuse (1967), which I also watched recently. I don’t think I like the young Rohmer at all.

Actually, Loïc says:

Tu refuses le surnaturel Chrétien,

mais tu fonces a tombeau ouvert

dans les trucs les plus farfelus

et on t'a a tous les coups

Qui ça on... Mais les charlatans

So more like: you refuse the Christian supernatural but rush headlong into the craziest things, into the arms of charlatans.

He also remembers a bit of a poem by Victor Hugo, “Ce que dit la bouche l’ombre“—apparently translated into English as “What the Mouth of Darkness Says.”

Maybe one of you can help me sort this out, I have no time now, this is what he quotes:

Donc, une bête va, vient, rugit, hurle, mord ;

Un arbre est là, dressant ses branches hérissées,

Une dalle s’effondre au milieu des chaussées

Que la charrette écrase et que l’hiver détruit,

Et, sous ces épaisseurs de matière et de nuit,

Arbre, bête, pavé, poids que rien ne soulève,

Dans cette profondeur terrible, une âme rêve !

Que fait-elle ? Elle songe à Dieu !

Original: https://fr.wikisource.org/wiki/Les_Contemplations/Ce_que_dit_la_bouche_d%E2%80%99ombre

A little mystery. Here’s a little review of Stress Positions.

Stress Positions

Cynical bottle-drama à la Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf (which I loved) or the Boys in the Band (which I hated). All three of these films have a problem which we might also recognize from the structure of fad diets: are we weak or are we wrong?

For example you could say that Terry (John Early) has his personal and political hangups in absolutely the wrong place, but he’s also a “loser.” Karla (Theda Hammel) has some really nasty theories about the totally transactional character of gay life, a negative concept of trans womanhood as an escape, a love-hate or maybe better to say dependence-resentment relationship with non-trans women, but one could also say that she just doesn’t know how to keep her hands out of the cookie jar, or to follow through on her own supposed convictions to change her life. So we don’t quite know if they are weak (failing to live up to ideas) or wrong (their ideas are no good). Of course both.

Initially I wondered about this diluting the film’s quality as a satire: it’s too discursive to be a simple mockery of human weakness (though there is a lot of slapstick and sexual indignity), but also the characters don’t present a good versions of their ideas, in another sense the film isn’t discursive enough. We might get as much as five minutes of the run-time devoted to Americans not knowing geography, which is a true embarrassment, but it’s hard to show that and at the same time to reach what Americans get actually and consequentially wrong.

But I came to see this not as a problem of narrative but as a problem of life. Terry and Karla are both weak and wrong, but they’ll never find out the latter. They are damned to the assumption that they’re failing to live up to something, and it will be too late when it occurs to them that what they have been trying to live up to is no life at all. And that starts to look like a social failure, perhaps a generational one, no one is there to push past the personal critique of hypocrisy and private moral failure to a real confrontation with orientations, commitments, ideas. That this confrontation doesn’t occur in the movie might actually account for its accuracy and power. You could tell a different story, but you’d have to tell it about different people.

In the Boys in the Band, there’s a throwaway line about one of the boys—using the gay “she” here—“who is she and who does she wish to be?” Somehow we aren’t reaching the second question.

In a way the film’s saddest portrait was of Bahlul (Qaher Harhash), who seems to understand nothing and turn the page on all of this. I think the film’s deepest cynicism is that Bahlul seems not to carry any residue of the contradictions of the people he’s depended on, or been entangled with, but instead skips a generation. He simply discards Terry and Karla, and walks off in the wig of the silent Coco, discarded in turn by the others. I think this is nastier than it has to be, but makes sense given where the movie stops. I think the film invites us to do the same, which is where its cynicism seems a little bit overdone. Life is not over if you had bad ideas in your twenties and limited sexual currency in your thirties. Take it from me.

Most of the light in the film came from the character of Ronald (Faheem Ali), the delivery driver who is the only one really open to others, trusting, who can step into a lot of different worlds. He’s alive in his body, and he steps up in that same body to help someone, and he pays a heavy cost. He also fucks. He illustrates a deep principle: that those who love will be taken advantage of and may die for it, and that those who can’t love are dead already. He seems to be the only living one here. He certainly isn’t righteous, he makes it clear that he’s motivated by pleasure, money, adventure—I think the film gives us just enough time with him to see that he’s what’s missing, apparently a morally unremarkable person, and a rude one, a person who isn’t locked down, in a city that is. That is a vision of full humanity, and it’s not a bad one, though it’s low to the ground. The actor is also just unbelievably sexy and charismatic, I haven’t seen him in anything else and it might have been his first role. I’ll be looking out for him.

Best line: “I don’t know, is it American to be GREEK?”