Rohmer in the 90s: four seasons

In the 1990s, Éric Rohmer made a cycle of films following the seasons, though not in order: A Tale of Springtime (1990), A Tale of Winter (1992), A Tale of Summer (1996), A Tale of Autumn (1998) — since he filmed them out of order I felt equally comfortable seeing them out of order. I'm going to stitch together the "reviews" here that I wrote of each. As you'll see I'm not a critic, but more and more I like to write in response to everything I experience. When I don't, it's like I wasn't there.

My schema for the seasons:

Springtime — adolescence — re-inscription of desire beyond the familial circuit

Winter — early adulthood — fidelity to adolescent intensity — first nostalgia, the one which can be totally believed

Summer — mid-20s — height of worldly energy, always wasted in confusion — contempt

Autumn — the light is better here but it will last a short time — paganism — the life in life — that we persist after these energies have run their course in us

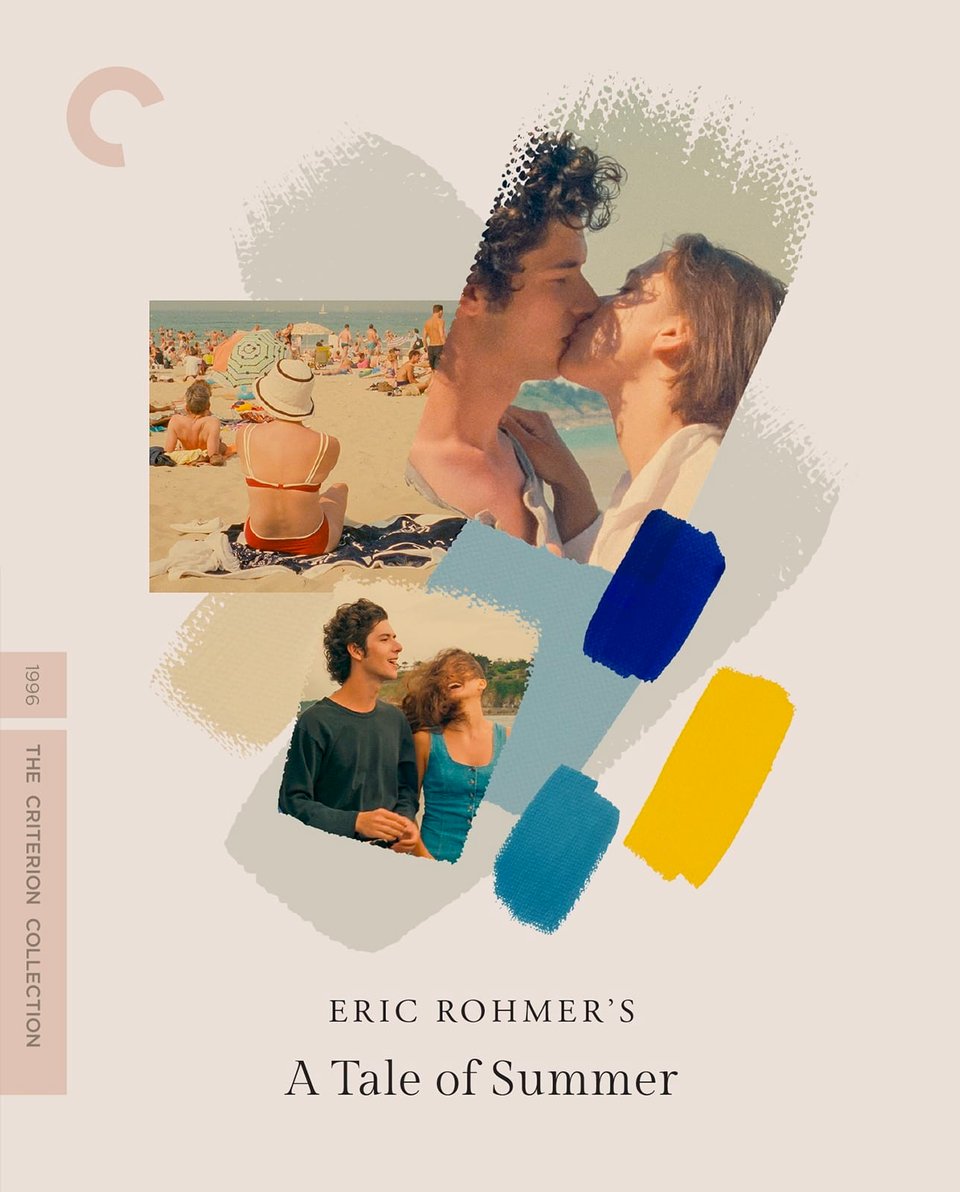

A Tale of Summer (1990)

simply the best movie I've ever seen. I love Margot so much. why can't people decide? why can't they try? love is betrayed every day. I feel sick

(August 2023)

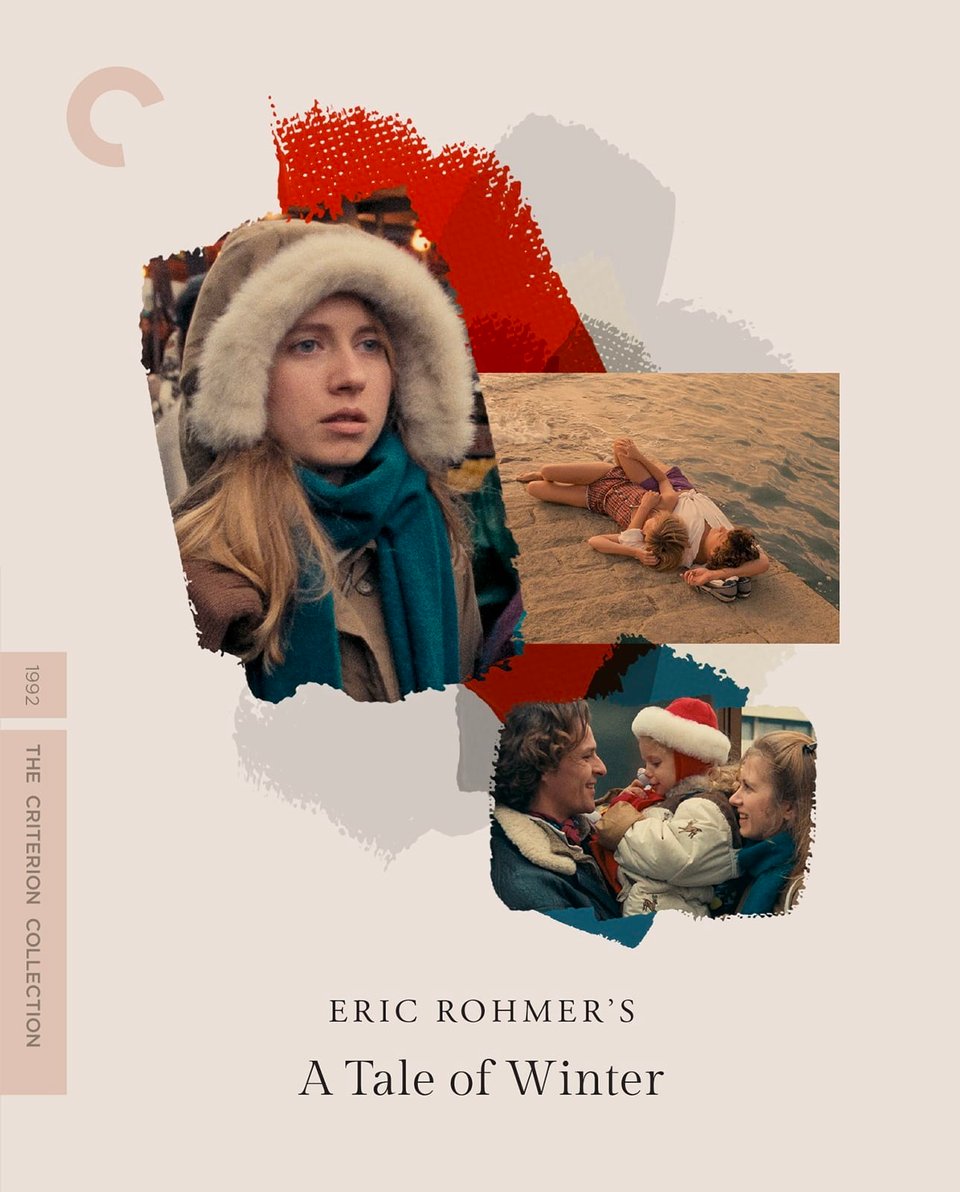

A Tale of Winter (1992)

Je pleure de joie.

Every Rohmer film I've seen seems to be an argument that life was everything that happened on the way to life, to the true life, or what we had taken for it. What you took for the waiting room. One thinks of Kafka's "Before the Law."

This observation is basic, or appears so because Rohmer prefers the palette of inarticulate beautiful young people in love. Even in Winter, the colors are very bright, naive. Octavio Paz once said of Joan Miró that he "painted like a child five thousand years old." That is Rohmer too, an eternal young adult, one who can tell the same story more and more truly, of the life we only got to live once. And now it's over. So we think we know. But we don't. It's something that comes to each of us in our lives as a surprise, as it does to each of Rohmer's characters, caught between innocence and experience, usually for the first time, in perfect natural light and without makeup.

We ought to respect naiveté, and Rohmer does, without condescension. It's not a question of some part of ourselves that can't catch up, which we might regard in a pitying or sentimental light, as what is infantile, puppyish, vulnerable, but fundamentally nostalgic, mistaken, an internal limit which is resentfully accommodated by our heady or earthy and in any case adjusted adult selves.

What I think that Rohmer shows here is the way the beauty of the life which goes unrecognized by the dreamer is also something which depended all along on that very same structure of anticipation and anxiety—and faith and puppy love and the one that got away and the inner conviction that you are somehow not of this world (family romance?)—even for the comparatively adjusted, the ones for whom infinity is foreclosed: the chthonic Maxence, the rational Loïc—they need Félicie. So do we. The tears of joy are simultaneously a comprehension of the limits of joy. They are not comprehended.

(February 2024)

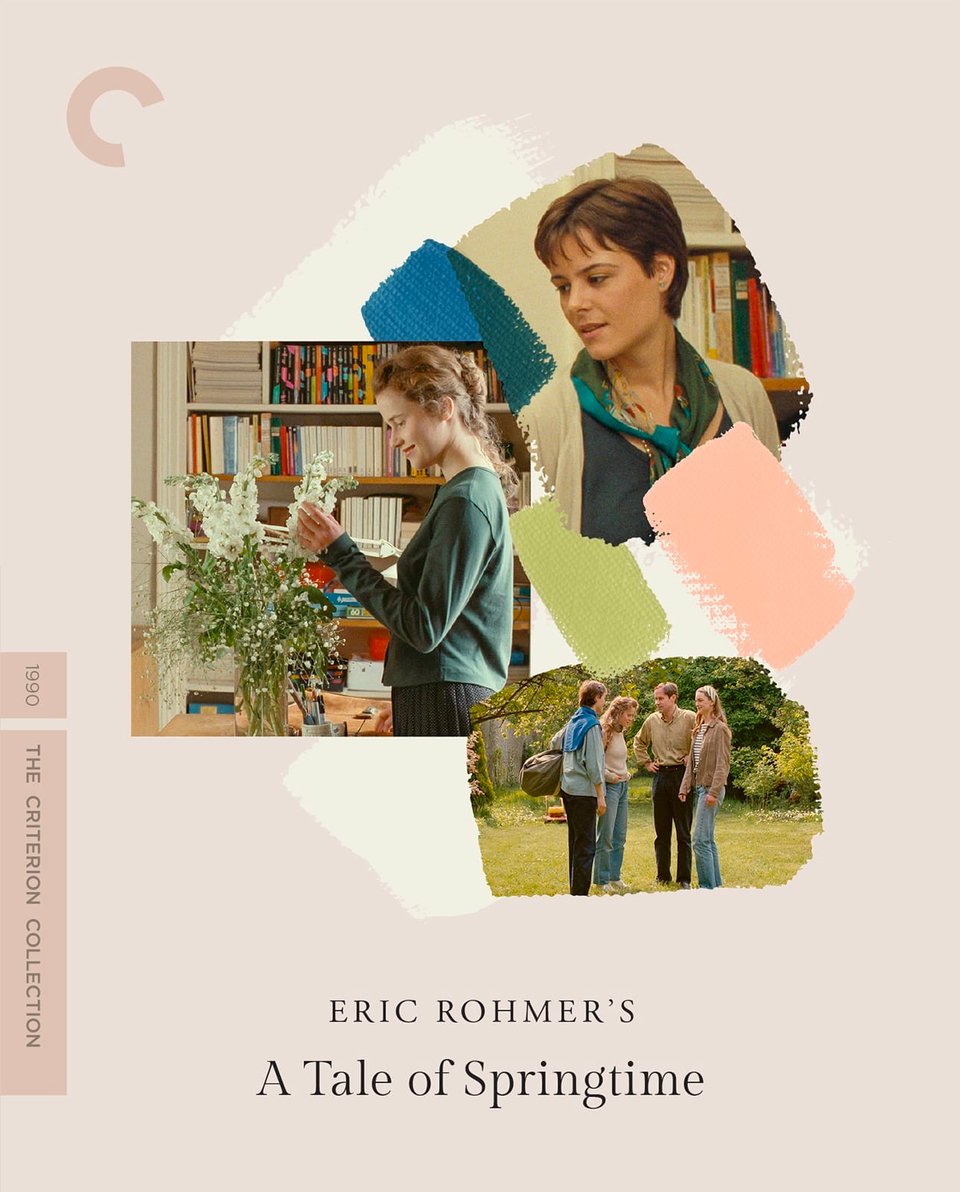

A Tale of Springtime (1990)

Not my favourite season but a completely accurate picture of what it's like to have friends who are under thirty.

Jeanne's hesitation and passivity is what one has to understand here. Her acceptance of the kiss, her "I don't fall madly in love," giving up her apartment, staying with a slob, getting into this situation in the first place. It seems that everywhere she is waiting for a feeling that would convince or force her to begin living. Perhaps the discussion of Kant in the middle of the film is meant to suggest this as well, the distinction drawn between the transcendental and the transcendent. It is as though Jeanne has given up transcendent objects but forgotten to refocus her emotional lens. She waits for a God she no longer believes in.

All of this makes her nearly imperturbable. Except by a desire which barely touches the surface, for her younger friend. Too young. It won't happen and it shouldn't. Rohmer is smart about this, and really gives you time to feel that Natacha is a teenager, whose immaturity is always a dominating factor.

What does Jeanne's imperturbability mean to young Natacha? Jeanne presents the perfect solution to the phallic power of her father, which drives her mad. She is jealous of her father's lovers, often her own age. And I think this is not a matter of a competitive, incestuous drive, but that they relate to his phallic power and disrupt her fantasy of it. She wants to win control of this interaction. She hates them for falling under his power, and simultaneously for revealing the low character of his power, his ordinary failings. They castrate him.

Jeanne on the other hand could be sacrificed to the paternal phallus and emerge from the fire unscathed. Unfortunately, what Natacha loves about Jeanne is an imagined mastery of transcendent objects, while for Jeanne it is more a matter of having given them up via philosophy, or perhaps of having weaker feelings in that area. In any case a misrecognition.

There are suggestions everywhere of a lesbian desire that might not run through the paternal circuit, or the phallic one. But this is only glimpsed by the characters, and never at the same moment.

Curious about Jeanne reading Valery Larbaud—I only know him through Ron Padgett's translations, here's one. Jeanne, wake up!

THE GIFT OF ONESELF

I offer myself to each as his reward.

Here it is, even before you deserved it.

There is something in me,

In the deepest part of me, at the center of me,

Something infinitely barren

Like the tops of the highest mountains,

Something comparable to the blind spot in the retina,

And with no echo,

And yet which sees and hears,

A being with a life of its own, which nonetheless

Lives my whole life, and listens, impassive,

To all the chitchat of my consciousness.

A being made of nothing, if that’s possible,

Insensitive to my physical suffering,

That doesn’t weep when I weep,

That doesn’t laugh when I laugh,

That doesn’t blush when I do something shameful,

And that doesn’t moan when my heart is aching,

That doesn’t make a move and gives no advice,

But seems to say eternally:

“I’m here, indifferent to everything.”

Maybe it is as empty as emptiness is,

But so big that Good and Evil together

Do not fill it.

Hatred dies of suffocation there

And the greatest love never penetrates it.

So take all of me: the meaning of these poems,

Not what can be read, but what comes through in spite of me:

Take, take, you have nothing.

Wherever I go, in the whole world,

I always meet,

Around me as in me,

The unfillable Void,

The unconquerable Nothing.

Valery Larbaud, trans. Padgett, Zavatsky

(March 2024)

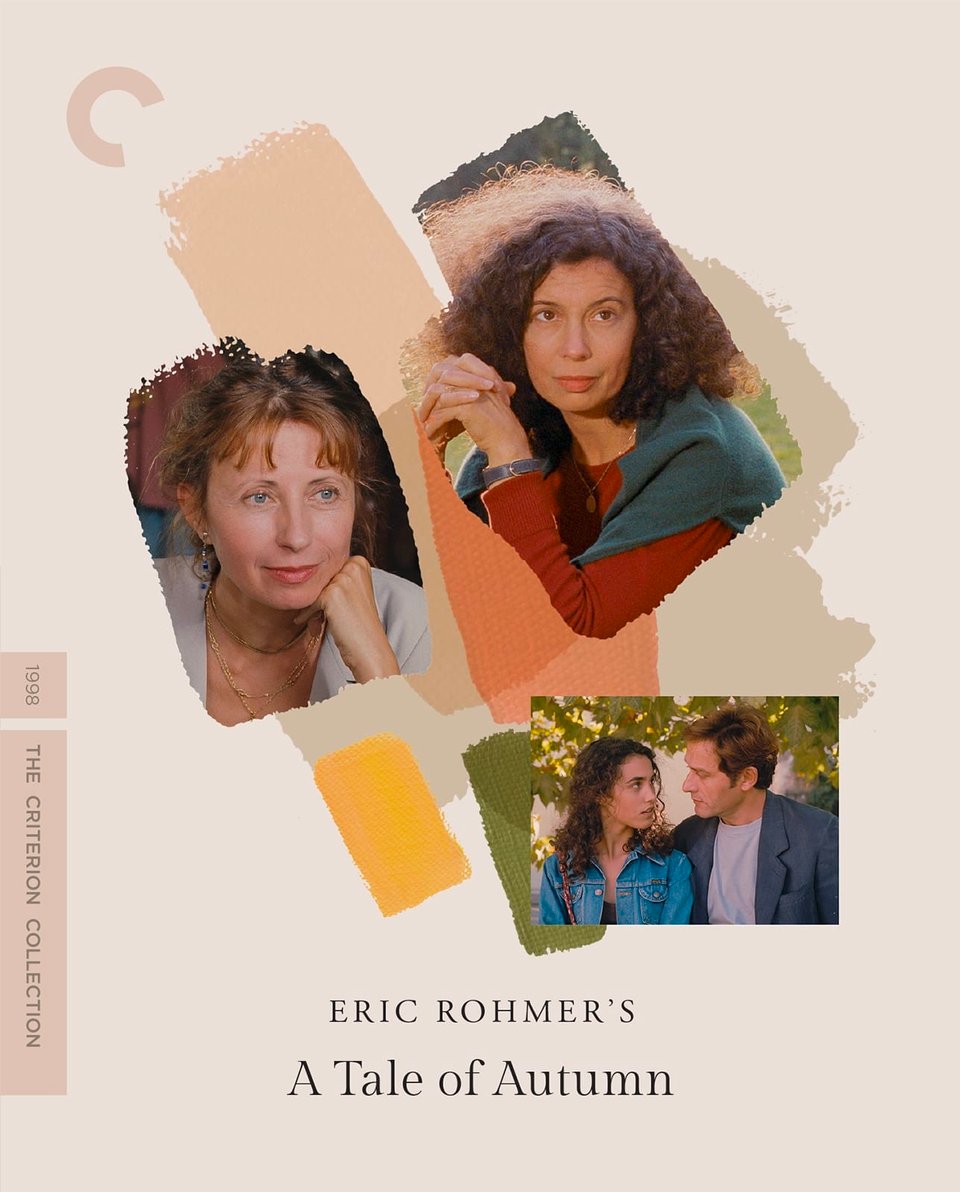

A Tale of Autumn (1998)

Could be a painting. The motion here is infinitesimal. The scene that will stay with me the most is a moment outside of the plot, the harvest party dance, Marie Rivière's enigmatic look over the shoulder of her husband—do we learn his name?—in this scene she is Marie Rivière, and is every character she has ever played for Rohmer, and none.

Subtle in its moral commentary compared to other Rohmer films. I would even say it is not about its characters. Of course they err and they strive and they love, but we are removed from all of that.

There's a moment in the film that I think is key. Young Rosine says at one point that she wishes to preserve her friendship with the louche Etienne, her former philosophy professor and sometimes lover, by placing him in a relationship with Magali, her substitute-mother, the film's empty center. She says she can seal him in a taboo, which I like to imagine both as taming him, and as ambering the version of him that she wishes she could still love, without paying the price of love: subjection to an emotionally stunted middle aged man.

We can feel a pagan spirit here. Taboo and prohibition repurposed, subverted. Feast days turned fertility rituals—back to the roots and not worse for the circuit. We see a wedding and the film doesn't give a damn about the bride or groom. We see a harvest festival and the film doesn't give a damn about the harvest. And even the structured relations. They are all rather occasions for an obscure vitality, something which belongs to the countryside and has not been extinguished by age or by change. What we are is what it wraps and braces. Every straight line is a maypole.

Still, mostly I was thinking about Marie Rivière.

(March 2024)