Cookie Monster: another night out

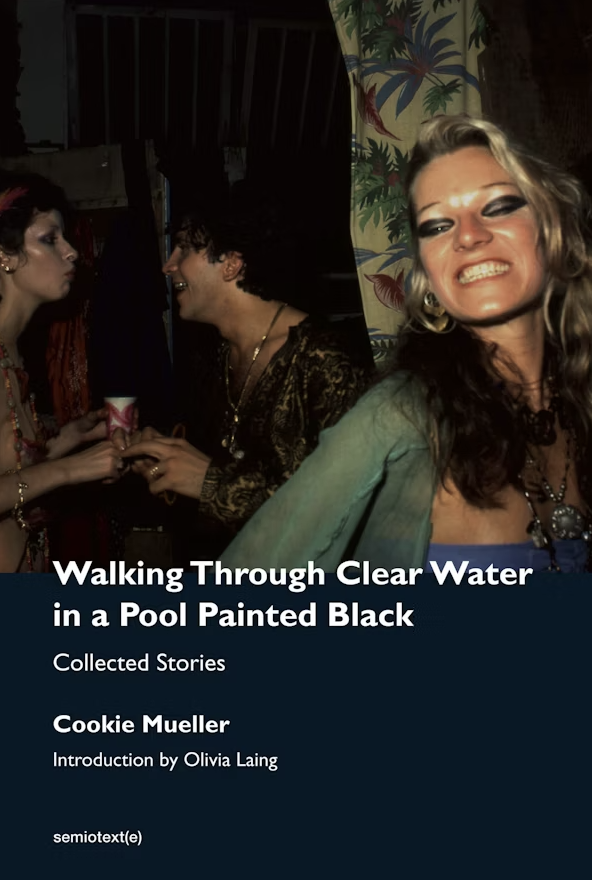

I spoke last night (2024-03-04) at an event at the Poetry Project for what would have been Cookie Mueller's 75th birthday, along with Kay Gabriel, Max Mueller, Lizzi Bougatsos, Gia Gonzales, Amos Poe, Kris Lee, Nicole's Revenge, Chi Chi Valenti, Gary Indiana, and a recording of Cookie Mueller herself. I had some nerves about this one, but it ended up being a great night.

I was a little bit nervous to read my piece, which I thought of as a bit of creative misreading and critique, trying to place Cookie in frame more as an author than as a character, or as she had been to many of the attendees, a friend. People seemed to be cool with it.

I'm not sure if they'll upload video, but if they do, it'll be here, and there's lots of interesting recordings: https://www.youtube.com/@ThePoetryProject

Cookie Monster

Close call in 1979 — Cookie’s friend Sam is OD-ing in the bathroom and it’s his birthday and she brings him back from the brink—it isn’t hard, by booting tap water and table salt. That’s a folk remedy and you should probably know for yourself that it doesn’t work. But the guy gets up anyway, it wasn’t his time, and he’s not too much worse for the wear—and he’s up and he’s dancing and he’s pouring drinks for everybody else.

Here’s Cookie, minutes later:

“So what have you been doing lately?” this filmmaker asked me.

“Not much,” I shrugged. “You know … same old shit …”

It’s the same old shit. And she’s right. This is the same type of shit that we to say “happens.” But there’s something else here. You can hear her hearing herself. It’s not just a story about an experience, but perhaps about this place of almost silence that we can go to, it’s about holding an experience at bay, and how that shows up in how we talk and how we write. Total intensity, then cool dismissal. And it’s one move.

After all what is this? Gonzo auto-fiction? AA-esque competitive confessional? War stories? There’s this carapace of matter-of-factness, minimization, the residue of an adolescent strategy of worldliness, still proving that you can handle it, that you aren’t fazed by it, and then in the end letting your own unfazedness displace the phenomenon. Perhaps you can’t say what it felt like or even in the moment, that you felt anything at all. Only, now here’s the question, who’s she got to prove it to? Maybe all of you?

I’m interested in the fact that Cookie seems to speak to our moment, even that a room like this would fill up. Perhaps we can sharpen something about our appreciation if we look at her as an inverted saint, her life as a freewheeling masochism, the mirror of Simone Weil—impossible lives, impossible people, yet oddly incredibly easy objects of identification. Or perhaps we could see her as presenting narrative and practical strategies for assimilating the material we are quick to label as “traumatic,” that she reminds us of ways not to be broken by such experiences. Or maybe we just think of Cookie as someone who went further than the rest of us—at least in terms of dosages—and who brought something back.

Now I want to read a very early story, which I found to be her truest, to try to hear as we read it the way that reality seems to drain out of the situation in real time, leaving only the serial, and pure alienation. Every statement is a type, it’s an example—it’s an example of what someone might have said even in the moment someone is really saying it.

Let me tell you how I would have put it if I were me. I’d have said I already lived this life in a dream I can’t remember.

Another good thing you could say about it is that it doesn’t declare any easy victories on behalf of the subculture.

Alien—1965

I was always leaving. Every time I left I had a different hair color and I would be standing on the porch saying goodbye to the older couple in the living room. I didn't have anything in common with them except that we shared a few inherited chromosomes, the identical last name, and the same bathroom.

They would be protesting. Screaming. It became a tune, with the same refrain, and the same lyrics, “If you leave now, you'll have no future. If you leave now, you'll be a bum.”

“I'll be back in the fall when school starts.” Or “I'll be back after the weekend.”

“If you leave now, don't dare come back. How are you going to live? You don't have any money. Why do you have to leave?”

“It's natural. It's a biological urge. Like little birds testing their wings. I can't help myself.”

There were a bunch of people waiting for me, in the street in front of the house, honking the horn of a cream T-bird, or a black Impala convertible, or a pale blue Rambler.

“Bye, I'll see you soon.”

“Do you want some money?”

“No. Thanks anyway. Bye.”

We sped off. I told my friends in the car that I was an alien to my parents. It was better that I didn't hang around there too much. At this point it would always dawn on me that there was another problem. Not only was I alien to my parents, but I was an alien to my friends.

I was really sad to miss this reading at Segue. Charles North and Ron Padgett. I feel like Ron Padgett is one of the poets who can find me even when I feel totally disconnected from poetry (as I sort of do now, but Daniel prescribed Clark Coolidge and it's sort of working). I hope I get another chance to see him. He's not very egotistical, he's written all of these books about his friends: one about Ted Berrigan, one about Joe Brainard, one about his dad, now there's one in the works about Dick Gallup. And why not? But I hope someday someone can write the book about Ron, because he was the best of all of them. His poems are often small, but really right. I love him so much.

Now here's a tune that sounds good loud.

In an echo left on the mountainside

If anywhere I reside

And the gifts of the years I wasted here on the battle lines

I am still alive and what's coming true

Is the signal to my return, oh

Find me here on the ground and in need of you