A story from a dusty drawer: "The Ruby of Sindbâd"

Dear readers,

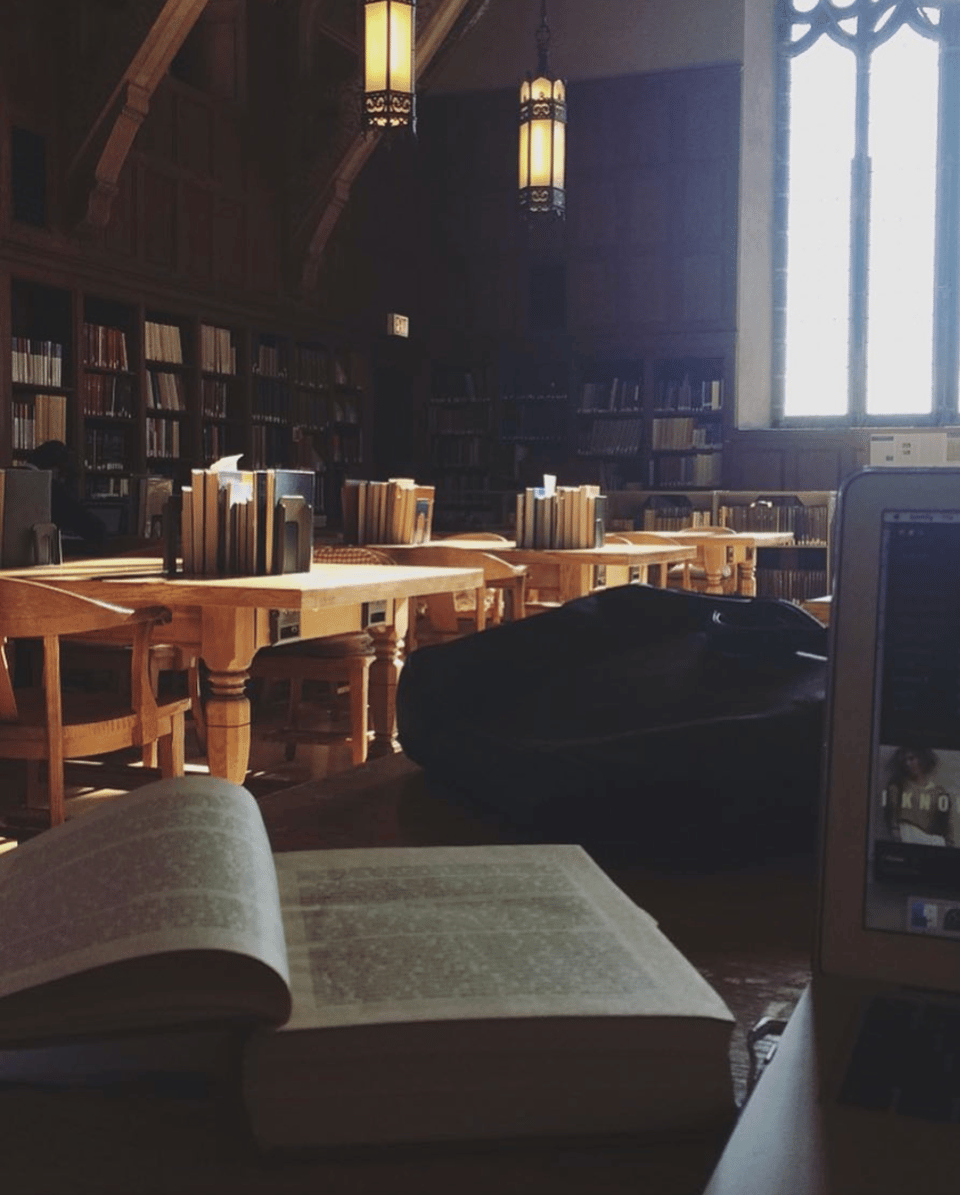

Graduate school put me through the wringer, but when I look back on those days with an eye for fondness, I think of sunshine pouring through the stained glass windows of the Oriental Institute reading room, gilding floating dust motes and the pages of my reading.

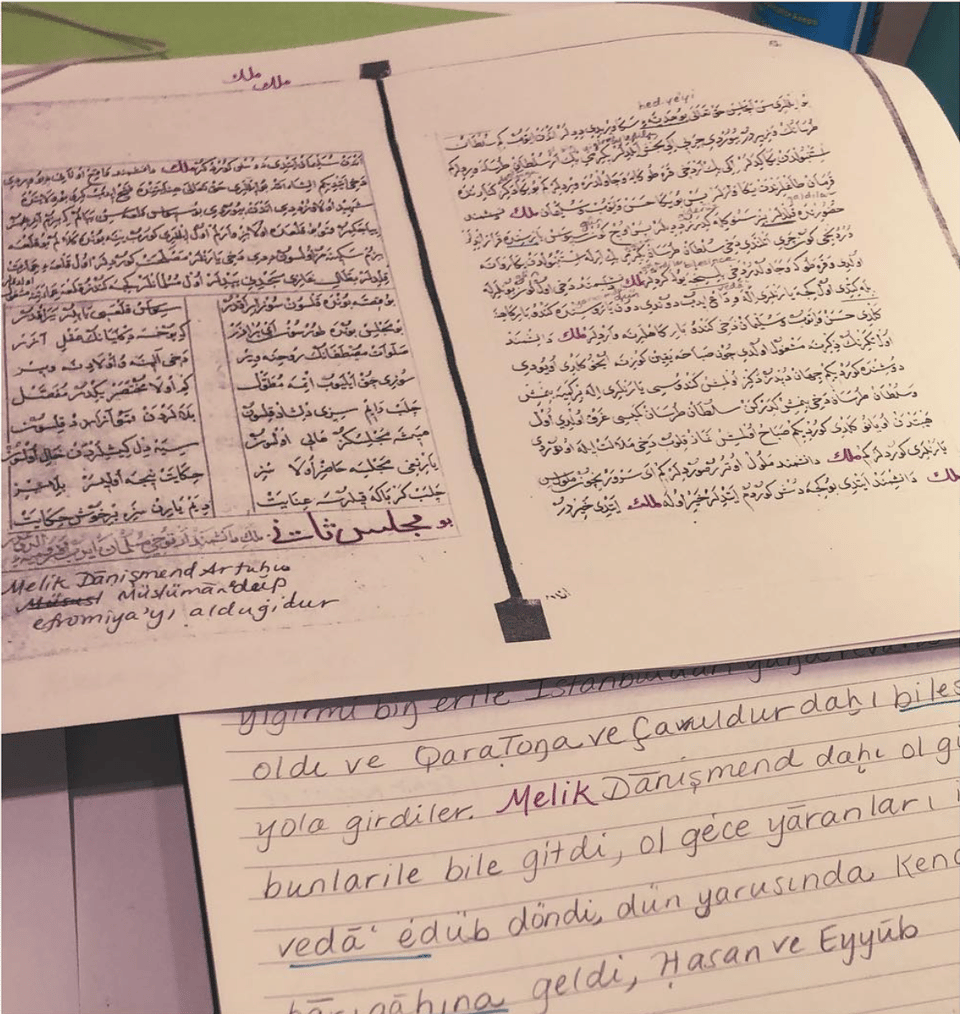

I spent countlesss hours there diligently translating Old Anatolian Turkish, and, for a fun* palate cleanser (*I am a masochist), thunking Haim’s Farhang-e Bozorg on the table before me and diving into some Nizami. I read epics and romances, gazals and mesnevis, fairy tales and folklore. The academy is rife with politics and sexism and bullying, but there, alone in the quiet of the reading room, surrounded by pencil shavings and dictionaries and annotated translation drafts, I was in paradise.

When reflecting on our respective research paths, a fellow PhD candidate once told me, “you’re always looking for the story.” I can’t help it. It’s how I’m wired.

I spent years pouring fairy tales and romances and medieval Islamic history into my head, and, instead of an article or conference presentation, on a quiet December afternoon in 2018, this story is what tumbled back out.

I hope you enjoy it.

xxxx

The Ruby of Sindbâd

“Hasht Behesht is a mirror for princes,” the prince scoffs, his Turki accent pinching the vowels of the book’s title short. Il-Arslan lounges across from me on embroidered pillows. His long muscular legs, clothed in loose silk trousers, stretch across plush Gulestani rugs imported—or so he says—from Kashan. More likely taken in a military raid, like so many of the other luxurious items that deck this palace of Gurganj, the capital of Khwarazm. Like the bronze sconces that line the red-stone walls of the citadel, the crystal goblets that servants fill with amber honey-wine and sour-sweet sherbat at his father’s banquets.

Like me.

“I warn you, girl. I will not be entertained by didactic fables.” He plucks a date from the silver plate before him, tosses it into his mouth. “I had my fill of talking jackals at the hands of my tutor.”

“Where I am from, Hasht Behesht is not a mirror for princes.” I keep my voice low, my eyes downcast. I must tread carefully, a gazelle before the half-sated lion. “It is a mirror of all creation, mortal and immortal. It is a pomegranate with a thousand enchanted seeds, a tapestry woven with all the intoxicating flavors of the pari realm. Each tale is the end of all beginnings, the beginning of a thousand ends. Some tales, they say, still bear the touch of pari poets: they will fill the listener’s goblet with wisdom. You will hear them and grow rich, blessings raining upon your head for the rest of your days. Other tales may divine the day of your death.”

He takes the date pit from his mouth. His are almond-shaped, dark and set deep in an arrogant, tanned face; strands of ebony hair fall to broad shoulders, loosened from his topknot by an evening of drinking with his viziers. His kaftan is the navy of the Sea of Khazar at dusk, embroidered with the green thorns and blush petals of Kashan roses. Another import, no doubt.

A mother-of-pearl scabbard is fastened casually at his belt. In it rests a kılıç, its graceful curve both ornament and fang, as deadly to me as it is bewitching. Khwarazmian steel, it is said, is impervious to the cunning arts of pari tongues, and the most dangerous weapon a man can wield in this world or in mine.

I must ignore the knife. I must not think about the throats it has slit. Night has only just settled over the river; dawn is many hours away.

I still have time.

I swallow the knot in my throat as the prince’s eyes narrow, as he considers me in flickering candlelight.

“Do you have a name, girl?”

“Shahrzad.”

My name an old-fashioned one for Ashkad, that cold, mountainous country west of the sea. The country from which Il-Arslan’s men stole me, the one he believes is my homeland. I wear it with pride, perhaps because I, too, am old-fashioned. Time slips through hourglasses at a different pace outside of Ani, my walled city of thorns and jasmine on the shores of the Sea of Khazar. Generations of men were born and withered to dust as I grew to the threshold of maturity, now a girl just the right age—or so Il-Arslan thinks—to serve the whims of a wine-soaked warlord. To entertain him.

And entertain him I must. My plan depends on it.

Mother-of-pearl winks in golden candlelight as the prince waves a dismissive hand. “Go on, then,” he says. “Tell me your tales.”

My life depends on it.

“Yeki bud, yeki nabud,” I begin, dropping my eyes demurely to the carpet. Once upon a time. “Long ago, in the western realms of the ancient king Khosrow, a pari lived by the sea.”

I keep my gaze low as I speak, but know by the slowing of his breathing, by how still he sits, that Il-Arslan listens closely.

Whether his silence is the wariness of a predator or a listener’s rapt awe, I do not know.

I can only continue.

Gentle and steady as the creep of a tide, I pour all that I am into my voice as I tell the prince how the pari lived by the sea because he had found a cave in which to hide his treasure from man and monster alike.

“And what a treasure it was! Countless rubies, as bright as dawn and heavier than an armored soldier, black pearls collected by dragons from the depths of the southern seas. Silvery cloth woven from widows’ tears by the finest witches in Mogholistan, and enough gold to make the king Khosrow eye it with avarice, had he known of it. The pari’s treasure was safe in the cave, for it was guarded by the pari’s brother, a carnivorous rokh bird. The rokh was as broad across as a warhorse is long; when it spread its wings, it darkened the sun in the sky and whipped waves large enough to wreck ships on the rocky coast.

“It was such a shipwreck that brought the sailor Sindbâd to the pari’s cave one night. His crew dead, the fortune that would gain him the hand of a princess lost to the depths, he collapsed on the shore and wept. At last, turning his gaze to the heavens, he begged the stars for guidance: unlucky planet Keyvan was ascendant on the ecliptic, but his sign—the Mark of the Twins, the sign of all adventurers and madmen—urged him not to despair. Though he shivered and ached, he picked himself up, wiped the salt from his eyes, and walked up the coast to seek shelter.

“Sindbâd was a wily man, an orphan who was raised by witches and pious ascetics alike as he wandered from home to home, and he knew the traces of pari arts when he saw them. When he came across the mouth of the cave, he paused. Like any other wise man, he knew that crossing a pari threshold was flirting with his own end.

“Yet cross it he did.

“For Sindbâd loved the sister of the Shah of Khwarazm, and if he were to ever win her in marriage, he could not return east empty handed. If a pari dwelled within the cave, he thought he could ask it for a boon in exchange for a tooth, or trade seven years of his life in return for its immortal wisdom regarding his dilemma. Never did he expect to find such a treasure…”

Never does the prince suspect that as my voice fills the room, it slinks up to his body, caressing his muscled neck with a touch softer than a lover’s fingertips. For all his love of drink and luxury, Il-Arslan is an ox of a man; his reputation as a warlord was spread across the continent not by gossip, but by his own deeds. By his own strength.

It is that strength I beckon toward me. I coax it out of his body, my voice woven with the power of Hasht Behesht’s pari arts.

Il-Arslan’s strength slides out of him, a cloud of dark smoke in the flickering candlelight.

The prince cannot see it, but I must be careful. If he knew my designs… a single strike of the steel kılıç is all it would take to shred my spell and my body to ribbons.

“What happens next?”

My heart leaps to my throat.

Without moving, I use my own arts to snatch Il-Arslan’s strength from the air and coil it around my left wrist, a ghostly gauntlet pressed against my racing pulse.

“Well, Sindbâd was stunned into silence. Who wouldn’t be?” I clear my throat and repeat the charm to smooth my faltering voice. “Yeki bud, yeki nabud…” I now dance on the edge of a knife. One false move before my task is done, and my life is forfeit. “Cunning Sindbâd knew he could not rejoice at his good fortune just yet. For the discovery of treasure can be a curse rather than gift if one’s celebration invites the evil eye, invites black sorcery to fall upon one’s head. He kept calm, and quietly filled his one threadbare bag with the smallest rubies he could find: he left the cave with seven in all, each as large as a man’s fist. No more, no less.

“The rokh was waiting for him when he emerged.”

Il-Arslan’s dark glittering eyes are fastened on me. He has not moved, and has not noticed that his famed strength has left him.

My next quarry is more difficult.

I mean to steal Il-Arslan’s youth.

“The rokh was furious that a mortal man would be so brash as to stroll unannounced into his pari brother’s cave, and it grew angrier still when it saw that Sindbâd carried a bag full of rubies at his side as he picked his way down the rocky coast. The rokh dove from the sky to attack Sindbâd.

“Sindbâd heard a great cry, and looked up to see the sky blackened by the shadow of the rokh. The sea roared, whipped into a frenzy by the monstrous bird’s wings. He knew he could not flee the rokh weighed down by the burden of the seven rubies, and dropped his bag. He snatched but one jewel, and, stuffing it into his shirt, broke into a run. But it was too late—no man, no matter how cunning or swift, could escape the mighty rokh. It dove from the sky to the shore, and devoured Sindbâd in a single mouthful.”

Coy and soft, my voice slips under Il-Arslan’s skin and finds his youth: it is hot and wild, wound tightly around his beating heart.

Come, I beckon it. Come.

Bit by bit, it loosens its hold. It bends slowly toward me.

“Even when all hope seemed lost, Sindbâd would not be defeated,” I continue, pouring everything I have into my voice. My knees tremble from the effort; my clasped hands are slick. Though the room is far from warm, a bead of sweat slips down the back of my scalp, tracing a path down my neck. Obey me, I begged Il-Arslan’s youth. I am your master now. “Dark and foul though it was in the rokh’s belly, he still had the ruby. He drew it from within his shirt, and using its sharp polished edge as a knife, he struck the inside of the rokh. The rokh tumbled through the sky, shrieking in agony as it fell nearer and nearer to the stormy sea. Desperate and maddened by the lack of air, by the fear that his frail mortal life was about to be snatched away from him, Sindbâd struck again. Once, twice, thrice—”

With one fierce yank, Il-Arslan’s youth slips free.

“Sindbâd broke free and fell to the sea below.”

It, too, appears on the air between me and the prince like a cloud, fierce and blazing. It draws near me when I beckon. Now that I have broken it free from Il-Arslan, it knows me to be its master.

“What happens next?”

I meet Il-Arslan’s eyes. His hair has lost its luster; it is limp and pale grey as his sunken face. His teeth are yellow as tea-stained linen and his hands are spotted with age and trembling.

Victory wells bright in my chest as his youth winds around my right wrist, hot as a golden bracelet fresh from the forge.

But the tale is not finished yet. I am not finished yet.

And I must act quickly, before Il-Arslan notices the change that has come over him.

“Sindbâd’s brow was blessed with good fortune. When he surfaced, he found a piece of driftwood and clung to it. His sign, the Mark of the Twins, watched over him and guided him east; at long last, he washed up on the eastern shore of the Sea of Khazar, in the territory of the Shah of Khwarazm. He had nothing left to bear testament to his adventure save the single ruby and his own life.

“He walked across the Qızılqum desert to the shores of the great river Syr Derya. There, the sandstone citadel of Gurganj rose before him, red against the twilight as the ruby he carried. He entered the city and begged an audience with the Shah of Khwarazm. The Shah granted him this honor, but when Sindbâd offered him his tale and the single ruby as the price for the princess’s hand, the Shah laughed at him.

“‘What need have I for this dull stone?’ he cried. ‘What is it compared to what I have?’ Sindbâd listened in shock as the king began to describe his wealth. Not only was he the sovereign of the emerald land between Syr Derya and its sister river Amu Derya, he had conquered half of Gulestan as well, and the riches of that great land poured into the coffers of the citadel. So wealthy was the Shah that once, he had collected the seven most beautiful maidens from the seven climes of the world. He kept them in the seven towers of his palace, one for each night of the week: he owned a girl from Gulestan, but also had stolen the daughter of the sultan of Kairouan, and the most striking maidens from Mogholistan, Rus, Rûm, Khwarazm and… and Ashkad.”

I inhale deeply. I am so close I can almost taste the sour-sweet sherbat of victory, but I have no more tale from Hasht Behesht, no more spell to weave. Like Sindbâd in the rokh’s belly, I am left with nothing but a single ruby clenched in my fist:

My truth.

“Every night of the week, the Shah told the maiden he visited that she had the chance to win her freedom by impressing him with her talents. The girl from Rûm danced until her feet blistered and bled, until the carpet wore thin. The girl from Mogholistan sang until her lips were chapped, until her voice grew brittle and broke. But it was never enough to keep the Shah entertained. At the end of every night, as the sky paled in the east, the Shah slept with the girl and slit her throat to silence her weeping. One by one, the girls died. Red sheets greeted the red dawn in the red city.”

My voice trails off as I look at Il-Arslan. I meet the fury in his eyes with my own.

“How does this story end?” he asks. His voice as soft as the belly of an adder as he reaches for his kılıç.

But he is an empty shell of the lion he once was, and this gazelle has grown bold.

How does this story end? I hold out a hand to him, my palm open and waiting. This story is mine, and whatever end is embroidered in my stars lies on so distant a horizon I cannot see it.

“It doesn’t,” I say, and with the curl of my index finger, I steal the breath from his lips.

Il-Arslan’s eyes bulge from his head. He gasps and gapes like a fish on the hot deck of a ship as his breath weaves through the space between us. It settles obediently in my open palm, limp and docile as a milk-drunk kitten.

“Shahrzad,” he cries, clawing at his throat. “No. Forgive me, I—”

I ignore him, my eyes on his breath in my palm. It is blue as incense smoke, wet and slick as fresh-spilled blood.

“Yeki bud, yeki nabud…” I whisper.

I swallow it.

And a new tale begins.

#

Once upon a time, a pari girl steals the body of a prince. She wears it more proudly than her gowns of sea mist and dew; she throws back her new broad shoulders and holds her head high as she looks down at the withered prince.

The prince shrinks back in horror at the sight of his own strength, his own youth, his own breath woven together over someone else’s body. At the sight of his own reflection.

A grim smile plays across her lips as the pari snaps her calloused fingers. The prince turns to ash. A sudden wind forces the shutters of the room’s windows open, scattering his remains and snuffing out the candles.

The prince’s kılıç, still nestled in its mother-of-pearl scabbard, falls to the rug.

Moonlight fills the room, draping its silver mantle over the rugs and cushions before her. The pari fills her deep lungs once, and once again.

She steps forward, her silk trousers swishing against her long, muscular legs. She crouches, takes a date from the silver plate, and toys with its texture in her new mouth. She runs her tongue over it and her teeth before spitting out the pit.

She considers the kılıç. A long moment passes.

She takes it and fastens it to her own belt.

When the sun rises, she will take the prince’s finest warhorse from the stable—the bay mare with stockinged feet and proud eyes. No one will stop them as they follow the sun across the parched expanse of the Qızılqum, retracing Sindbâd’s footsteps to the shores of the Sea of Khazar. There they will turn southwest. A girl riding alone on the Gulestan road wouldn’t last three days, but not a soul would dare stop a Khwarazmian warlord as he canters past the orchards and rose gardens of Kashan.

And when the pari reaches the rolling hills of her home and sees the high walls of Ani, she will renter her realm and seek her older brothers and sisters. She cannot wait to see the wonder on their faces as she discards her disguise, as she casts the strength and youth and breath of the prince Il-Arslan into the sea.

The kılıç, however, she will keep.

Khwarazmian steel is difficult to come by in the walled city of Ani, and despite the power woven into the tales Hasht Behesht, she has learned that it is never a bad idea to have steel impervious to the arts of paris at her side.

After all, Hasht Behesht is naught but a mirror for princes.