The Wesley Willis interviews: Matt Heaton of The Flavor Channel

Object Permanence by Leor Galil

This is the first in a series of interviews with people who’ve appeared in songs by Wesley Willis. I’ve long been curious about how Willis’s music functioned as a document of his everyday reality. If you’ve heard a few Willis songs, you’re likely familiar with the routines: the chintzy keyboard melodies, gruff vocals bellowed in half-sung bursts, and lyrical codas that function as (and in some cases, actually are) advertising slogans. I’ve been particularly taken by the diaristic elements of Willis’s music. He’s made songs about friends he loves, Chicagoans he’d crossed paths with, and bands he’d seen at one of a variety of clubs he’d regularly haunt. Willis released hundreds of songs over the course of roughly a decade. Not all his tracks speak to his daily experiences—unless I missed something in “I Wupped Batman’s Ass”—but plenty of other songs do capture something about Willis’s world. I hope to learn a little more about it with these conversations.

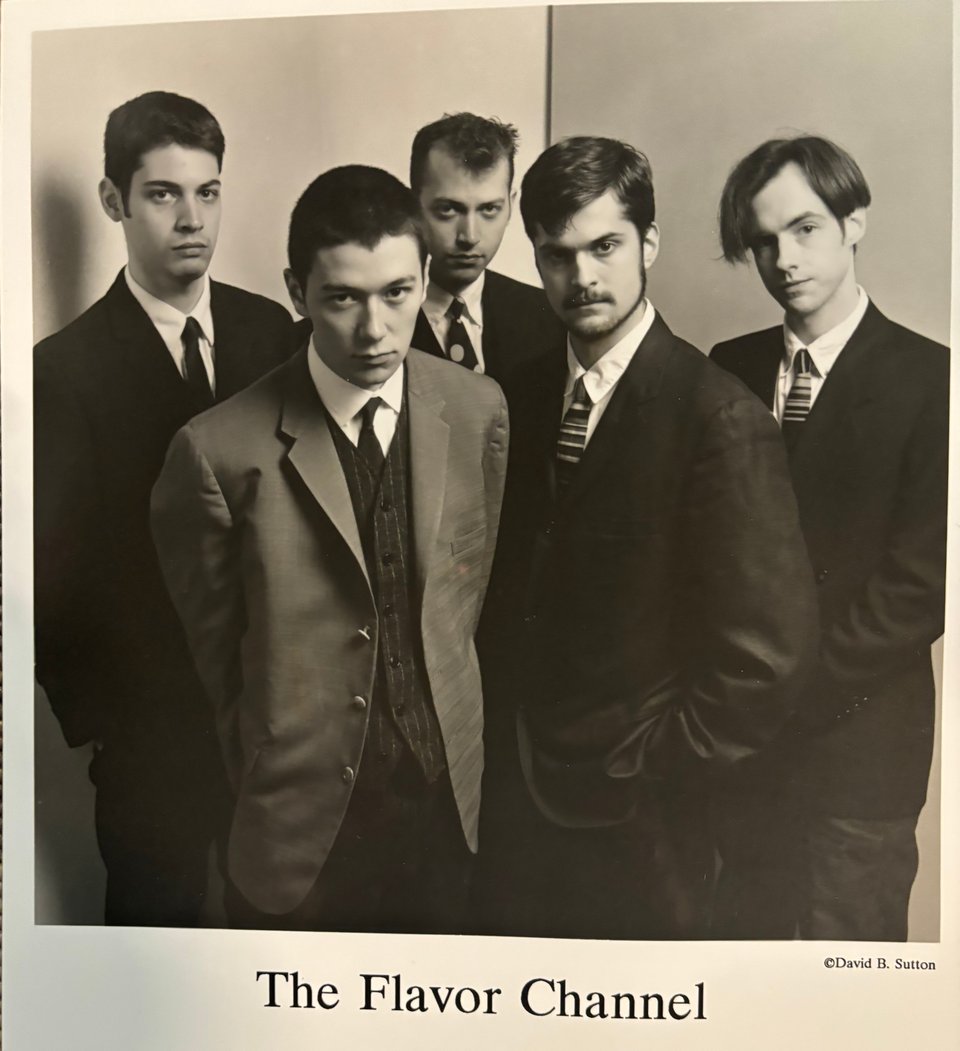

My first interview is with Matt Heaton. In the 1990s, he played guitar in a pop-oriented alternative band called The Flavor Channel, who were the subject of a song on Willis’s 1994 album Double Door. Two years later, The Flavor Channel released their debut full-length, Plexicom. The album landed at number three on Greg Kot’s roundup Chicago’s best indie-rock albums of 1996 for the Tribune: “This veteran band finally gets a proper CD release, and it’s a winning display of classic, British Invasion-style songcraft, flavored with bits of lounge pop, ‘Telstar’ and teen-angst balladry.”

As Heaton tells it, the group originally found inspiration from John Zorn—particularly his gonzo quasi-grindcore group Naked City—and they streamlined their style as the 1990s wore on. The Flavor Channel also self-released a cassette, put out a few singles, and contributed to a few compilations, including Marc's A Dick And Gar's A Drunk: The Johann's Face Story, which also features Smoking Popes, Alkaline Trio, and Apocalypse Hoboken. These days, Heaton lives in Boston, where he leads a surf-rock band called the Electric Heaters, performs children’s music, and plays traditional Irish music with his wife, Shannon. The following interview has been lightly edited and condensed.

When I reached out to you, you seemed really enthusiastic to talk about the Wesley Willis song about your old band—why?

Matt Heaton: The whole thing is such a kind of a crazy chapter in Chicago. It was definitely some kind of badge of honor if Wesley Willis would write a song about you, you know? We were very active in the scene, though we obviously didn’t hit it big. Everyone in the band is still pretty proud of the music we made and whatnot.

You put out a song on Johann’s Face—was your record also out on Johann’s Face?

Yeah, we had one album and a few singles, basically. There’s an album called Plexicom—I don’t know if he’s still selling CDs or anything, but you can stream it. We did a few singles, and we did a cassette, just a few releases.

How’d you form?

We were basically friends from college. Two thirds of them were playing in another band, I was playing in another band. We all went to Northwestern—our two bands had played gigs together, and we thought it might be nice if we joined forces. That’s kind of it.

What were the bands y’all were in beforehand?

Uh… let’s see. Theirs was called the Sleestaks, which is from The Land of the Lost. Mine was called Frustrated Picnic.

Did you mostly play around Northwestern?

Yeah, at that time, yeah—those earlier bands were kind of a campus concern for the most part.

Once you formed Flavor Channel, how’d you begin to establish yourself in the city?

We would play anywhere and everywhere that we could. Eventually we ended up playing at the clubs that were around: Lounge Ax, Metro, Avalon, some of which I’m sure aren’t there anymore. I would love to have a list of everywhere we played. I remember some loft parties in Wicker Park, these sort of odd… they weren’t really venues, but these places that hosted shows periodically. I don’t know if any of us would totally be able to remember. I just remember carrying a lot of heavy equipment up a lot of stairs.

Stylistically, how did y’all approach making music together? What did you want to do as a band?

It kind of evolved. It started out much weirder than it ended up. We got more, um… I wouldn’t go so far as to say poppy, but it was poppy-ier. The earliest stuff was just kind of odd—John Zorn and Naked City and that kind of thing, so we had a lot of quirky stuff. Victor Thompson, our singer, was sort of the main songwriter in the band… we kind of reined in some of our weirder tendencies, and I think it worked a lot better. As far as our influences at the time, we loved Pixies a lot… We liked David Bowie. It was kind of, like… more like slightly complicated pop-type music.

How’d you begin to find other people who were on your wavelength in the city? How’d you form a community in Chicago?

I haven’t lived in Chicago for, like, 25 years. But at the time, there was a scene—especially all the bands that played at Lounge Ax—there was a real sort of camaraderie. There was a period of time when, like, after all the bands in Seattle got signed—the grunge explosion or whatever—there were definitely some labels sniffing around Chicago thinking that it would be the next big thing. This was when, like, Veruca Salt and folks like that were around—Urge Overkill kinda made it. But there were a ton of bands like the Pulsars and Number One Cup come to mind immediately. Handsome Family was around. Everyone just kind of enjoyed each other’s music, and liked hanging out and all that. It was a really nice scene.

Who were y’all closest too?

Uh… like, who’d we hang out with?

Yeah, who were your friends?

Probably, like, the Pulsars, and then… Why don’t we just go with Pulsars and Number One Cup [laughs]. Spies Who Surf. Spies Who Surf were playing a lot back then. We never got to play with them, but I would’ve liked to, I loved those guys.

Where were y’all living? Did y’all live together?

Some people did at various times. I never lived with any of them, but sometimes two or three people would live together. People moved around a bit. I started out in Rogers Park, and ended up in Lincoln Square.

Where did everybody else live?

Here and there. We tended to rent really crappy rehearsal spaces in Wicker Park though, so that might’ve been the more of a headquarters.

How’d you get connected with Johann’s Face?

We must’ve… I honestly don’t know. The great failing of that band was that nobody was particularly organized. I’m not sure who knew [label cofounder] Marc [Ruvolo], but someone did, and so somehow it happened. Honest to God, people were just like, “OK, we’re gonna record now.” And I would say, “Oh, great, OK!” without really knowing too much about how that came to pass or anything. I always feel like if someone had been a little more… “business minded,” or if we had a manager or something, we probably would have done a little better than we did, but we certainly had a good time.

Earlier you mentioned the major label interest that happened in Chicago, obviously after Nirvana but also Liz Phair and the blowup of the local scene. Was that an interest for y’all—did you want to be bigger?

Oh hell yeah. Yeah, we would’ve loved it. I remember there was a magazine—I would have to dig it up, I can’t remember the name of the magazine now, but they did a big spread on a bunch of Chicago bands, and we were in there… There was a whole slew of Chicago bands that they were tagging as “Is this gonna be the next big thing?” Spoiler alert: none of us were.

You mentioned a cassette, the only thing I heard of yours was the CD y’all put out, Plexicom. Did the cassette come before that?

Yeah, that was sort of our first thing. That was called Ibid. We actually recorded that. There was this place that was, like, a nonprofit recording studio. It was really meant for people to do experimental music and tape things like that. At one point, we tracked a few things there, which, I wanna say it was a four-track machine—it was a very small thing. It’s a crazy-sounding collection of songs, ’cause we just went nuts with doing whatever we wanted to. They had a nice piano there, I think that was one of the reasons we did it there—and they were cheap. Cheap was always good for us.

When did you make that?

A few years before Plexicom. It was pretty early. Here I’m walking over to see if I can lay my hands on a copy, and if I can, if we actually put a year on it, both of which are dubious statements. Let me see… we just rearranged… It was… ’92, 1992.

How did that change the trajectory for the band? Did it?

It was cool to have something recorded. The college stations would play it. The cassette was never really anyone’s desired format. At that point CDs were, “Ooh, making a CD, that’s expensive.” But, you know, I feel like we did an awful lot of things that, if they had all happened closer together, we would have had more momentum. There was some rock station that had a local music show, and we went in there and played live in the studio, and a lot of people would hear that, because it was a pretty big station. I don’t know that the follow up was quite what it needed to be. But by the end, we were playing good gigs. We headlined at Lounge Ax, we played some good shows at Metro and some of the other spots. I don’t want to make us sound too incompetent.

How did you feel about the CD once you put it out in 1996?

Oh, couldn’t have been more proud. We loved that record. I still love that record, I think it’s a great record. The sounds on it are awesome, the songs are great. I’m a big fan.

The Wesley Willis song. How’d y’all meet Wesley?

I mean, if you hung out at rock clubs at that point in time, you were gonna meet Wesley. We had no idea that that was happening until Double Door came out. I don’t know who got it first. We’d gotten together for rehearsal, and someone was like, “OK, I got something to play for you.” And there it was, our very own Wesley Willis song.

What did you think of it at the time?

I think the same thing I think of it now. It’s such a fascinating thing—the fact that he actually made this body of work. You’re talking to me about him now. It’s crazy. It’s very outsider-y music, in the kind of way that you think of Shooby Taylor. I can’t say I would put it on repeat play and listen to it all day and all night, but I do get a kick out of listening to it. It makes me smile. Same with many of his other songs.

Do you have other songs of his that—obviously don’t have the same meaning as the one as your band, but do you have other songs of his that you go to?

My favorite, which actually would have been the Wesley Willis Fiasco, not a solo effort—“The Bar is Closed (You Ain’t Gettin’ Any Liquor Tonight).” That was always a kick, which, as somebody pointed out, “Yeah, he may have heard that once or twice.” That would be my pick.

The song he wrote about y’all is about y’all playing at the Double Door, do you remember seeing him when you played the Double Door at any point?

I don’t know. We played the Double Door a few times, and we had definitely seen him at the Double Door. I don’t know if that was the time that he was writing about or what, but definitely remembered seeing him. He was kind of hard to miss.

Did you develop more of a rapport with him, or was he someone you’d run into at shows?

More that—he was someone you would run into. I don’t know that he would necessarily recognize us unless we were actually playing anyway.

What happened with your band?

After playing together for a fair bit of time, people just started moving. Our keyboard player decided to go back to school, but in California, which can put a crimp in rehearsals. My wife and I moved to Colorado for a couple years. So it just sort of ran its course. A lot of us are still in touch. Actually, Victor, the singer, has got a new band called the Expected Highs, and their first record’s coming out real soon—I think in June or something. I actually went over and played some guitar with him on that, which was an awful lot of fun.

You went to Colorado. How’d you end up in Boston?

Boston—kind of for the music scene. We went to Colorado, we lived there for two or three years, and it was mostly because there… was more nature and outdoors and blah blah blah, after driving around Chicago a lot. And then after a couple of years we were like, “Ah, we kind of need to be back in a city.” My wife had some family living in Boston at the time. We also play traditional Irish music, and there’s a great scene for that—just decided to give it a try. And that was in 2001, so it worked.

You’re doing traditional Irish music and children’s music, correct?

Yep, I sort of have three irons in the fire. I play music for kids, I play trad Irish music, I also have a surf band—like surf-rock band that actually does a couple Flavor Channel songs every now and then. So those are my three things.

You’ve sort of already talked about this a couple times, but looking back on the scope of your work in music, what does the Flavor Channel mean to you now, and what does this Wesley Willis song mean to you?

The Flavor Channel, I mean, I’m really proud of that music. I’m glad we made that music. We’ve all talked about this at times, there’s an alternate reality where the Flavor Channel is, like, Wilco or something, where we sort of continued to play, got really big, and yada yada yada. But I’m not bitter about it or anything. It didn’t end nastily or anything like that. The fact that the Wesley song was just one of these crazy things that, like, “See, this actually did happen.” Here you are, talking to me about it and writing about it. I’m rambling here, but it’s cool, I like it. In addition to the music that we made, it’s a kind of cool memento of that time, and that scene, and that world.