The Wesley Willis interviews: James VanOsdol, former Q101 on-air personality

Object Permanence by Leor Galil

In 1993, Chicago alternative station Q101 launched The Local Music Showcase, a Chicago-focused program originally helmed by Carla Leonardo. When Leonardo quit in 1995, James VanOsdol took over the show. "The fact that my involvement with the show continues to define my on-air work is fine by me," VanOsdol wrote in his 2012 book, We Appreciate Your Enthusiasm: The Oral History of Q101. "I had more fun hosting the show than anything else I've done in my FM broadcasting career."

The same year VanOsdol landed his Local Music Showcase gig, Wesley Willis included a song about him on the Drag Disharmony Hell Ride album. "You work hard on the job at Q101," Willis declares on the track. VanOsdol left the station in 2000, and he remains dedicated to alternative music and audio; he runs a podcast called Car Con Carne, which is close to completing 1,000 episodes. This following interview has been lightly edited and condensed.

How'd you meet Wesley?

James VanOsdol: Wesley was omnipresent. He was at every club. He'd sit on the stairs at Metro. He'd be sitting in the corner at Thurston's or Double Door or Empty Bottle. Wesley Willis, in some respects, helped me get my first on-air job at Q101 back in the 1990s. I was working in the programming department at Q101, and the woman who was hosting the local music showcase resigned to take a job out of state. I wanted to do the show. I wanted to be involved with local music, but I had zero on-air experience.

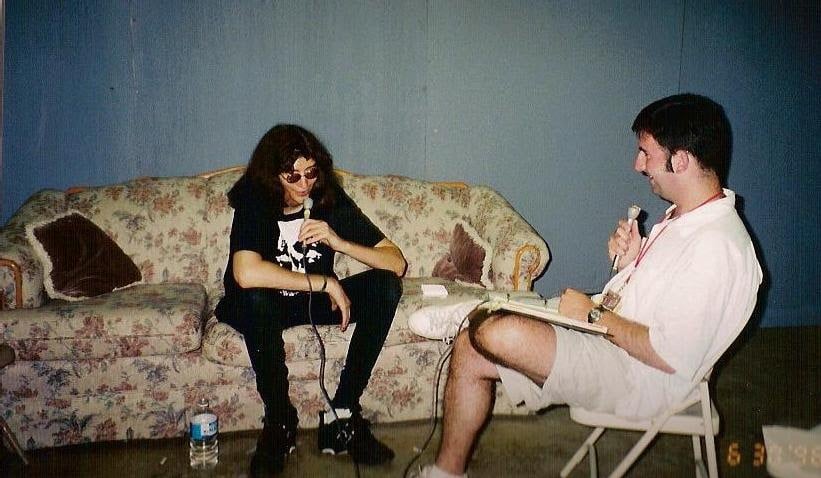

My program director at the time—his name was Bill Gamble—said, "You need to make a tape. You need to prove to me you can actually do a radio show." So I went out with a tape recorder, went to three different Chicago venues, and interviewed three different local artists, including Wesley Willis at Lounge Ax. I spliced them all together into a mock radio show, what my local music show would sound like. I put probably a 30-second clip of my Wesley Willis interview into my demo tape. That demo tape got me a job hosting The Local Music Showcase at Q101, which launched a much bigger and far-reaching radio career.

Do you still have that demo tape?

Oh God, no. I'm not just saying that. I've done away with most traces of what I perceive to be a really awkward time in my broadcast career. In hindsight, it would be cool if I still had it. But I definitely do not.

I remember reading in your oral history of Q101 that you had destroyed all your recordings of your Columbia College Radio days.

That was a dance format—me introducing Cajmere didn't quite work.

Take me back then. What got you interested in radio?

I'd always wanted to be involved in radio, because it was a way to be around music without having to know how to play it. For me, being on the radio wasn't about being goofy or wacky or wanting to flex radio pipes. I just wanted an excuse to be around music for eight to 10 hours a day. That goes back to childhood. I was one of those kids who knew what he wanted to do from a very early age, which I think is kind of rare—perhaps even more so now. I was always in love with the idea of sharing and playing music.

House music wasn't the best fit. What made alternative work for you and your personality?

It was just the stuff I came up with. In the 80s, when I was in junior high school and high school, I was listening to The Cure and Joy Division and Echo & the Bunnymen. That gave way to The Minutemen and Robyn Hitchcock & the Egyptians. That was just the stuff I listened to; that was the stuff I was fluent in.

How'd you get a sense of the scene in Chicago, going through Columbia College and eventually landing at Q101?

Well, Columbia College didn't really give a good sense of the scene. Back when I went there, it was a commuter school. It was really hard to feel entrenched in any kind of community at Columbia. For me, I just went to lots of shows. It sounds crazy through the lens of today. I keep sounding like the man here, but back in the 90s, there was always stuff going on. You could bounce from a show at Metro—and Metro was definitely more local music focused back in the 90s—you'd bounce from a show at Metro to a show at Empty Bottle, or I guess it was a newer club back then, but Lounge Ax or Thurston's or Double Door.

You first landed at Q101 as an intern, correct?

Yes.

How long were you working there before you got the job doing the local show on Sunday night?

Probably a year and a half.

You submitted the demo, you got the job—from your book, I recall that it wasn't a job a lot of people were vying for. How did you make that show yours?

It was mine by ownership when I got it, but it takes a while. I think with any creative, artistic—any pursuit, it takes a while for you to find your voice. For me, it was no different. I made a ton of mistakes when I started. I don't think I was a fantastic DJ out of the gate. It took time. I think I was well positioned with local music simply by having the show. But I think it took a couple years for me to really make it mine and have my voice, and have it be something that was somewhat memorable.

What changed with your relationship with the local scene once you got that show?

Well, I mean, there was demands beyond the radio. Richard Milne at XRT had Local Anesthetic. Chris Payne at Rock 103.5 WRCX had a show called Chicago Rocks. There were different angles. All three of us came at the scene from different directions. For local bands, this was a chance to get heard, and I think all three of us were inundated by artists who saw this as a very viable outlet to get their music out into the mainstream. Back in the day, even though it was a Sunday night program, a lot of people were listening to Q101, a lot of people shared that experience on the radio. I think it's wildly different now, but back in the day, people listened to the radio at the same time, and had the same experience, and for local bands, that was a big deal. I think it was a big deal.

A huge deal. Vocalo is kind of the only thing like that running these days, and that's possibly going off the air in a month.

For sure, yeah. One thing I talk about a lot is the need in the present day for music curation. You do it at the Reader with what you write, but I think the days of identifying who those trusted voices are have kind of been lost. Everything is kind of served up algorithmically. Having those trusted voices, whether it was Richard Milne at XRT or Chris at RCX, knowing who those people were who were going to turn you on to stuff that makes sense. I've gone through Spotify and YouTube Music and Apple Music, and have gone through every recommendation engine, and no one's really nailed it. No one's really served up the stuff that fits, or that gave me those "ah-ha!" vibes. For me, identifying those curators is so important to the modern day. I like to believe that was a role we served back then.

Is there a sense of when you felt like you became a trusted voice among locals?

I think I'm too self-deprecating to pinpoint that. I was de facto that person. I was the local music guy on the alternative radio station that, at one point, had a million people listening over the course of a week. By default, I served that role.

What did Wesley and his music play in your world?

Q101, back in the 90s, did two big radio festival shows. We've all seen those festival shows with, like, 10 bands that had nothing to do with each other, play over the course of one day—I kind of like that idea. But, one of them was the Twisted [Xmas] shows, which we did around Christmas time. For our second Twisted show, I forgot the year, maybe it was 1996 at the Allstate Arena, maybe it was the Horizon back then—I don't remember [edit: it was 1995 at Rosemont Horizon]—I invited Wesley Willis to do my stage announcement with me.

I was terrified of doing stage announcements. I had no experience doing them. I maybe did a Metro show once. Walking onstage at the Allstate Arena was horrifying to me. Back in the 90s, it was always a crap-shoot whether or not you were gonna get booed or have shit thrown at you because you represented the alternative station. I wanted to stack the deck and have someone fascinating onstage with me. I was scheduled to introduce Tripping Daisy at that show. I invited Wesley to come out onstage with me and do the introduction. So, he did that. I remember at the time, Jam Productions was not excited about having Wesley running free backstage at the Allstate—or Horizon.

But Wesley was definitely a part of what I did. I had the Wesley Willis Fiasco play in the studio at Q101 back in the day. We were saying this before you started recording; to me, Wesley Willis was emblematic of that Chicago music scene in the 90s, the sense of, "Anything can happen to anyone. Anyone can break out of that scene." Sonically, it was such a diverse amount of sounds. And Wesley, he was outsider art, and he broke through because there was nothing like Wesley Willis. I think he really was an example of what that particular moment in time was like for Chicago music.

Given the sense of possibility that he was emblematic of—pardon me for forming this question as I ask it...

I do that all the time.

When it's not radio it's a lot easier! Aside from that possibility, what did he bring to Chicago? What role did he play in the community, broadly?

It's a good question, and one I haven't really thought of to that detail. He was the fixture. He was the constant. You knew you were gonna see him somewhere. If there was a local, independent band, Wesley Willis probably wasn't far away. He was just kind of a given. I almost said he was the scene—that seems a little bold, but he was such a major fixture and figurehead of that moment in time. You knew you were gonna see him. If you went to enough shows over the course of a week, you were gonna run into Wesley Willis.

What kind of relationship did you develop with him?

I don't know that anyone really developed a relationship with Wesley. I've been head-butted by him numerous times. I am actually sitting in my home office, underneath a framed pen and ink drawing of the city that Wesley drew for me back in, like, 1998.

The relationship was no different from anyone else's. It wasn't really a relationship. I definitely felt—maybe protective is too extreme of a word—I definitely wanted to make sure that whatever he was doing, wherever he was, people were taking care of him, and people weren't being shitty with him, 'cause obviously he was troubled. He had so many issues, and it was very easy to see him get exploited. My relationship was he was part of what I did, he was part of the city. But I was also aware that, "Here's this guy with emotional problems, mental illness," and I really wanted people to do right by him. I do believe that he was finding joy in his own way, as best he could, but I also knew there were unscrupulous people out there.

Given that your relationship was largely tangential, how in your role could you provide the kind of care for him?

I couldn't—that was probably the wrong way to say it. Working within the music industry, which I was much more involved with back in the day, I had a program director who wanted Wesley to come into the studio and cut a bunch of liners for the radio station, and it was a bunch of kind of demeaning, shitty stuff. I made sure that that didn't happen. I can't think of a concrete example, other than that, but I was aware, in conversations, that Wesley, he was a local treasure, but also don't take advantage of him.

You mentioned Jam being a little weary of him backstage at that festival. Why?

Well, Wesley was a force of nature. Wesley did what Wesley wanted to do. One of my favorite lasting memories of my time at the radio station, my entire career at Q101, was Wesley Willis—Porno for Pyros played that [Twisted Xmas] show, Wesley Willis approaching Perry Farrell backstage. Perry was just walking by, and Wesley cornered him and insisted that Perry buy his CD from him. Which, I don't think moments get more classic than that. But, I get it, Jam's got a show to run. They run stuff on time, they run stuff efficiently. Wesley was a wrench in traditional operations.

Did Perry buy a CD?

He did, totally.

Incredible.

Incredible!

You mentioned the drawing Wesley made of the city. What's the perspective? What's it looking at?

It looks like it is basically from the Merchandise Mart. It's looking across the Chicago river; the Sears/Willis Tower is centered. The CNW sign is in there. It's pretty remarkable. There's a bridge over the Chicago river, I see a couple boats. It's colored, so the sky is blue with clouds, and the buildings are shaded in reds, pinks, yellows, and tans. It's pretty neat.

Did he present it to you like, "I made this for you." Or was he like, "Hey, 15 bucks?"

I asked him for it at one point, and he gave it to me later. And I paid him—I want to say I paid 40 bucks for it.

Those go for thousands now.

I'm a collector. I love collecting records, comic books, things like that. For me, I collect them because I enjoy them. I never want to sell things like that. It would never occur to me to sell this picture, nor would I want to sell my records or my comics. I buy them to enjoy them.

Speaking of enjoying records, when did you hear that song Wesley made about you?

Oh, he told me before it ever made CD that he wrote a song about me. He essentially gave me the box set at one point—like a stack of CDs, and Drag Disharmony Hell Ride was one of them. But he told me for a while, "I'm gonna write a song about you. I'm gonna write a song about you at Q101." And he did. And it basically said, "James VanOsdol works at Q101." That was the gist.

What'd you think of it when you first heard it?

The coolest! Are you kidding me? That was awesome. Again, thinking back to that period, Wesley was, in so many ways, the face of the Chicago music scene. To have that recognition, to have Wesley sing a song about you, it's kind of an acknowledgement. Like, "Oh, I guess I'm part of the fabric here. Cool."

When did that period end for you?

That's a great question. It came and went in waves. So much attention is put on the major label feeding frenzy that occurred in the 90s, where literally anyone seemed like they could get a record deal. People were divided into camps of, "The ambitious who wanted record deals," and then the other people who thought that they were impure for wanting such things. I feel like that period wrapped up at the end of the 90s. I really do think, the 90s were the 90s, and Wesley was emblematic of the 90s in Chicago. And then things change, as they did across the board, culturally, in the 21st Century.

Wesley didn't live much longer after that change. When was the last time you saw him?

Oh boy. I don't know. It had to have been in the late 90s, maybe 2000s. When I found out he died, I think it was of leukemia, I remember at the time thinking, "Oh my God, it's been a while since I've seen Wesley. How horrible."

How often do you think of him since?

It's funny, you reached out to me a couple days after someone I work with asked if I had ever met him. Like, just out of the blue. That's kind of the way it goes with Wesley Willis. I don't actively think about Wesley, per say, but he comes up a lot. I was talking about comic books with someone three or four months ago, and that person mentioned the fact—which I had forgotten about—that Wesley Willis was immortalized in Wonder Woman comic books. He finds his way back into my conscience, whether I expect it or not. Just happens this week it's come up twice.

Given that Wesley kind of helped you launch your career on radio, what does he mean to you and the scope of your life? Especially since you left Q101?

He represents a really exciting part of my life, a really fun period where it really did feel like you could do anything in this town. Whether it was being a successful musician, be an artist, be a painter, or a radio disc jockey, you could do anything. Wesley was part of that feeling. That's not to say he was the only one. There's so many inspirational and wonderful people of that period. But when I think of Wesley, that's what I think of; I get a big smile, thinking back to that era.

This is the second interview in a series focused on people who've appeared in Wesley Willis songs. The first interview was with The Flavor Channel's Matt Heaton.