We Ride at Midnight

In this issue, I explain the surrealistic quality of my life right now, recommend a book, share some news, update you on Garry Trudeau drawing his strip, and, for the main feature, look at the role of the fax machine in newspaper comics and editorial cartoons.

I Dream of Ben Day Dots

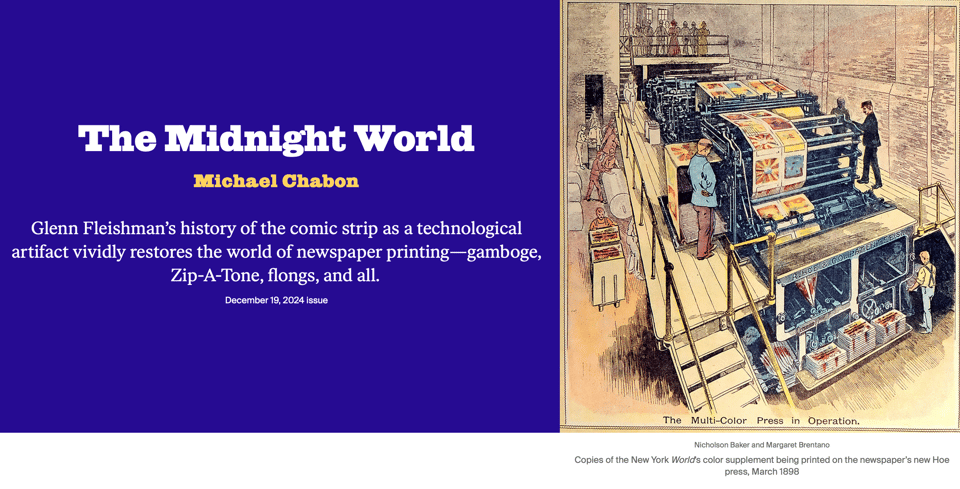

You likely already know that novelist, Pulitzer Prize-winner, and co-composer of a Monkees song Michael Chabon wrote the foreword for How Comics Were Made, combining reminiscences about spending time each summer with his grandparents and his grandfather’s late-night departure for his shift as a typesetter, and the kind of history we’ve forgotten and I’ve tried to recover.

The New York Review of Books told Michael they wanted to run the foreword as a freestanding essay, and it appears in the Dec. 19, 2024, cover date issue under the title “The Midnight World.” You can read this lightly modified version online with an NYRB account or register at no cost to read a single article. It appears in print in subscriber mailboxes and on newsstands soon.

I have to tell you it’s an absolutely bizarre experience to see my name in the Review of Books, like being in a kind of dream state.

Resuscitating the Lost History of an Early Female Cartoonist

Many threads came together to form my book, but one of the key bits of encouragement to pursue the comics angle came from curators Ann Lennon and Caitlin McGurk at the Billy Ireland Cartoon Library and Museum. I had suggested creating a video about how cartoons were syndicated during the era of metal relief printing, and they provided feedback and moral support during the pandemic.

They ultimately included the video playing continuously in their exhibition “Man Saves Comics! Bill Blackbeard’s Treasure of 20th Century Newspapers.” The show celebrated the 25th anniversary of the institution’s acquisition of Blackbeard remarkable newspaper collection. (You can see an archived version of the exhibition in a cleverly presented form.)

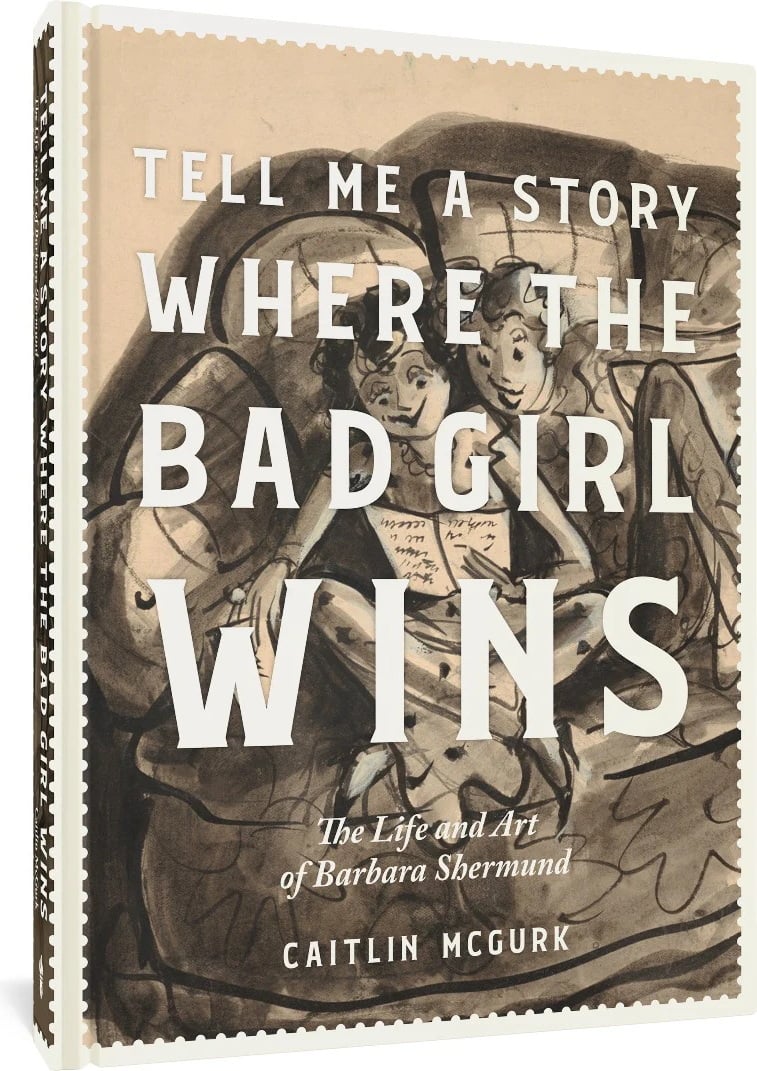

Caitlin had already been researching a book at this time for several years about Barbara Shermund. You may never have heard of her, even if you know something about 20th-century cartoonists. She was a very early contributor to the New Yorker, where her illustrations and cartoons appeared for decades, and gave a distinct voice to Esquire as one of the only women offered work.

Shermund’s work is rooted in freethinking women of all ages, though often young, who had sexual agency and were often coded or explicitly queer. Over time, she had to repress both aspects, producing more anodyne through excellent work. Eventually, she fell out of style and on somewhat hard times, though remained supported by friends and neighbors.

Shermund had no children or surviving spouse (her two marriages are mysteries in themselves) and no one to take on her legacy. Her estate attorney literally left her life’s work stacked outside her house, where parts of it blew away! Neighbors collected papers and artwork, a chunk of which have wound up at the Billy Ireland.

Caitlin’s remarkable book about a remarkable artist, Tell Me a Story Where the Bad Girl Wins: The Life and Art of Barbara Shermund, came out just a few weeks after mine, and I was happy to congratulate her at a presentation she did as part of a comics event in Seattle. It’s a gloriously large-format printing, letting you soak in the details of Shermund’s work. Caitlin’s scholarship is unparalleled and she tells a great story to boot.

Caitlin has ensured her memory will endure. Shermund’s niece (via a half-sibling) had located Shermund’s forgotten ashes in storage at a funeral home, and Caitlin helped her crowdfund a final, marked resting place near Barbara’s mother, a fitting tribute.

Why So (Present) Tense?

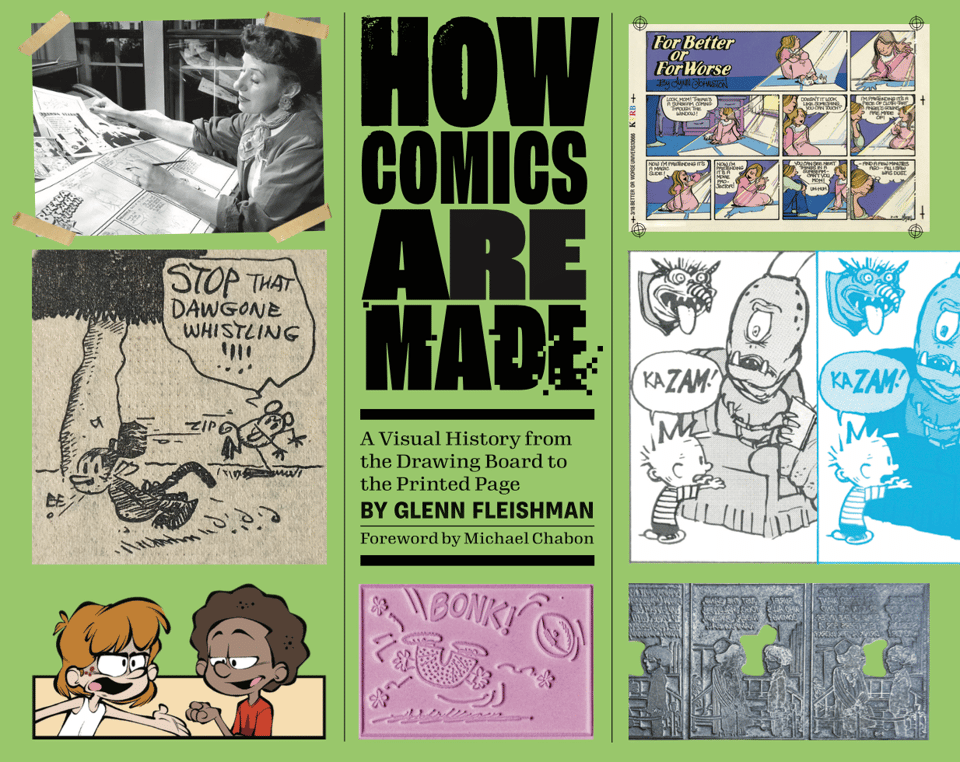

In another piece of book news, How Comics Were Made will appear next year in a new printing under the title How Comics Are Made and under the Andrews McMeel Publishing imprint. AMP acquired the rights to my book, and will release a “trade” edition—one that’s sold to bookstores, distributors, educational institutions, and so on—in June 2025.

Andrews McMeel Publishing is part of Andrews McMeel Universal and a sibling company to, one more time, Andrews McMeel Syndication, which runs GoComics and handles distribution of hundreds of comics, including most of the most-popular strips of the past and present. It’s a great fit for the book.

I worked closely with AMP to update the cover with some new images and other changes that they know will be more appealing to people picking the book up off the shelf. The new printing will have about 99.5% identical contents to the Kickstarter edition (one image was changed to a better one), and be in hardcover.

My Kickstarter edition remains available for purchase and immediate shipment while copies last.

You can also pre-order the Andrews McMeel version right now. The company has worldwide distribution partnerships, so if you live outside the United States and Canada and were daunted by the high shipping cost I had to charge or in a country I couldn’t ship to due to excessive costs, you’ll be able to buy the book directly from a bookseller in your country.

Drawing from Experience

A bit of follow-up! In the last issue, I noted that there’s a persistent incorrect notion that Garry Trudeau doesn’t draw Doonesbury, and explained the origin and how untrue it is. On Bluesky, in response to a link I posted to the issue, Patty Donnelly Adams responded—she’s worked with Trudeau for decades:

As one of Mr. Trudeau’s editors, he really does draw his own comics. [The myth persists] because the lies make for juicier headlines. I’ve worked with GBT for close to 44 years … so I know the truth. … He is absolutely wonderful. Pure genius, and a cool human to boot.

Social media has many drawbacks, but getting insight directly from the source is not one of them!

Just the Fax, Please

A number of years ago, maybe 30 or so, I was watching the classic Jimmy Stewart film Call Northside 777. Stewart is an intrepid reporter who discovers that a man may have been convicted of a murder 11 years earlier based on false evidence. He finds a photograph that juxtaposes the man with a date on a newspaper held by a newsboy that contradicts the evidence. All well and good.

To prove this to the parole board reviewing the prisoner’s case, Stewart brings them to a newsroom where, in another part of the state, enlargements from the negative of the photo are being faxed to them. This is supposed to be 1932! I was shocked.

It turns out, of course, that practical facsimile machines date back to the early 1900s, though they were specialized and exceptionally slow. First used to send photos more rapidly than they could be delivered by foot or vehicle, there was ultimately a commercial operated from the late 1930s through he early 1950s delivered a “newspaper” to a home fax machine! (Hey, people could also listen to music in their homes before radio broadcasting.)

In the 1970s, the first modern fax machines appeared, heralding a new age in unneeded communication passing among corporations and dramatically increasing the self-importance of people in power’s command of other people’s time.

But it also helped cartoonists tremendously!

A sidebar for the youth who never encountered a fax machine: A modern facsimile machine combined a cheap scanner, a paper-feed mechanism, a low-speed, dial-up modem, and a cheap thermal printer. Propping one or more sheets of paper into a feeder at the top of a fax and calling a dedicated fax number would slowly draw each page through and transmit a low- to medium-fidelity image to the other end, where it was poorly reproduced. Thermal paper didn’t receive ink, but responded to heat, allowing a kind of exposure; you can still see thermal printers in use for restaurant receipts.

Weirdly, while you can find a zillion photos of fax machines, finding general-purpose pictures of an actual fax on crummy thermal paper is seemingly impossible. PDF was one of many forces that killed the fax machine. And now back to the story…

Before the fax machine, cartoonists had to either send material by post or courier or they had to visit editors in person. This was incredibly inefficient and sometimes very expensive when express delivery was required. Cartoonists producing one-off panels and strips for magazines would make the rounds on appointed days each week in New York to meet editors in person. They formed a strong camaraderie with their colleagues—and it took a toll on their livers from the drinking that occurred between and after visits.

Once in syndication, cartoonists rarely strolled into an office unless they wanted an editor to buy them lunch. Though there was a massive cluster of comic strip creators who lived a short train or car ride from Manhattan in what were once the affordable and even semi-rural parts of western Connecticut. This let them send their work at the last minute or even bring it in themselves. (Read Cullen Murphy’s Cartoon County, a memoir and account of growing up among cartoonists and their families, including his father, John Cullen Murphy, and becoming the writer of Prince Valiant.)

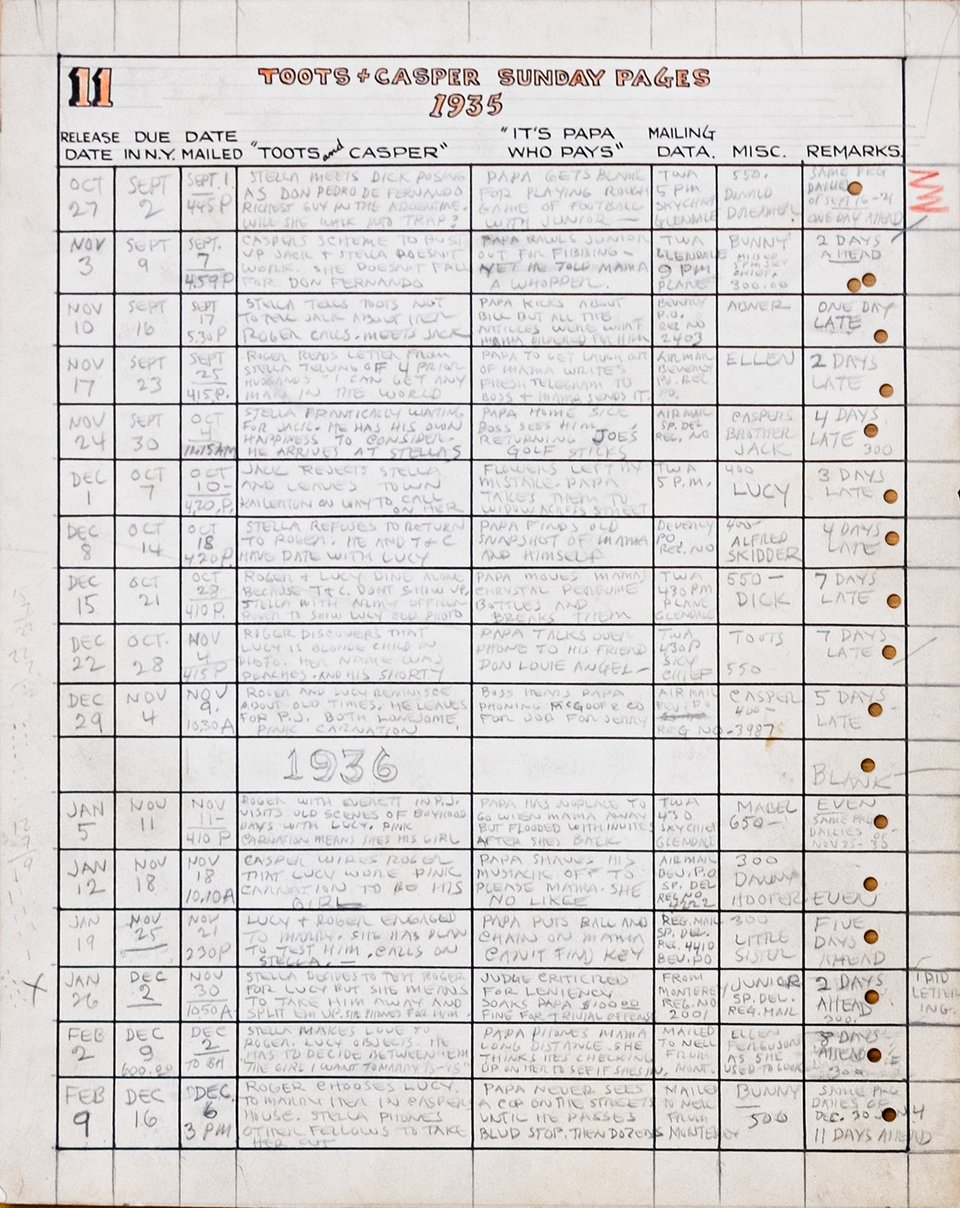

Syndicated cartoonists typically had extremely long lead times to allow for editing, changes, and reproductions. As far as I can tell, until at least the 1970s, newspaper artists had to be no less than five weeks ahead for dailies (typically submitting multiple weeks at once) and nine weeks for color Sundays. The Sunday deadline later became looser by a few weeks. Cartoonists who were late paid fines and often had to cover some or all of the costs of express shipping if that was required to get flongs or photostats to newspapers in time for them to make up their pages.

But the fax allowed more flexibility. I believe some cartoonists sent pencils earlier to editors for feedback or proofreading. Cartoonists and their inkers would fax material back and forth when timing required it. And editorial cartoonists may have even used fax machines to deliver finished work, particularly if they didn’t live close to the newspaper’s offices.

In researching the archives at the Billy Ireland, I came across sheafs of faxes in Mike Peters collected materials there. While Peters is best known today as the creator of Mother Goose and Grimm, a long-running comic strip, he’s also been producing regular editorial cartoons since at least 1969 and as recently as a few days ago. I believe he worked at a much larger size than production and then faxed using a fine or superfine setting available by the date of these strips (1989), which would have been 200 dpi or 400 dpi. Shot on a stat camera to reduction size, you would never know they were faxed. Any incidental glitches could be repaired in the art department—or Peters could have faxed again.

Perhaps most famously, we can circle back around to Garry Trudeau. He initially used the mail or express delivery to send his inker his penciled drawings. But as soon as the fax machine became a feasible alternative, he transmitted them that way.

Trudeau told me in 2017, when I asked if he drew oversized or used special settings, “No, I sent them 100%, but by then, my inking assistant, Don Carlton, was so used to my line that he could put them on a light box and trace in ink without difficulty.”

The fax machine died out for artists and business with one exception: they’re still in somewhat broad use in the American healthcare industry.

Add a comment: