The Yellow Kid Plays Football

Hello!

This issue features an update on How Comics Were Made and the odd history of an 1896 Yellow Kid printing plate.

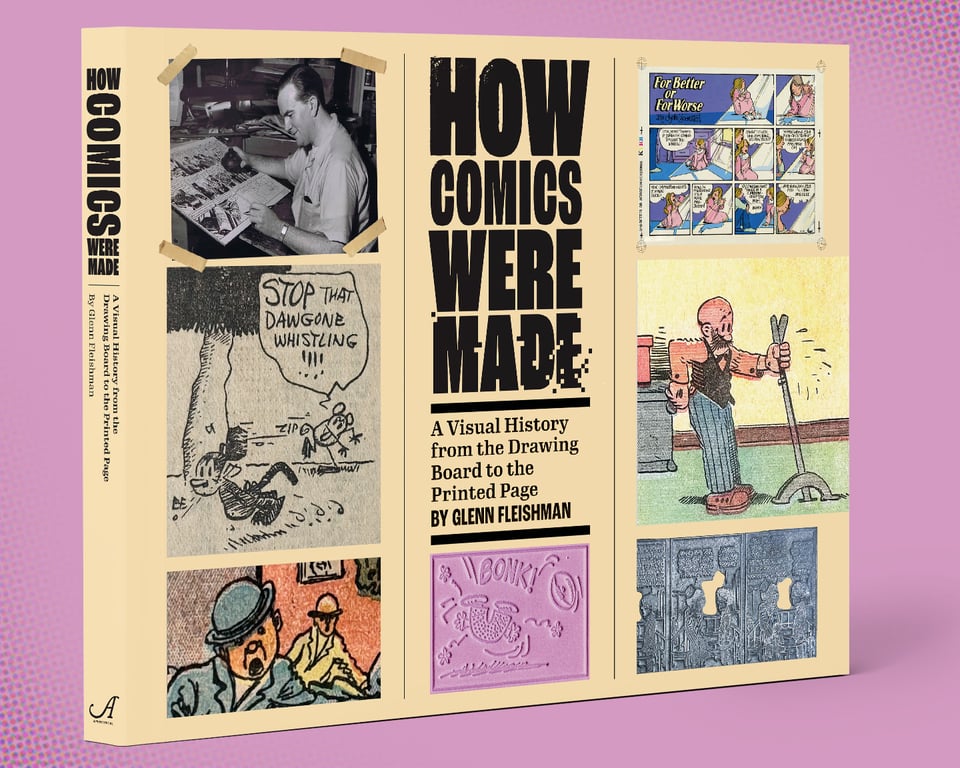

An Update on How Comics Were Made

The Kickstarter campaign for How Comics Were Made was a rousing success! The book funded at nearly $170,000 (over 110% of the goal), and I’m working diligently towards its delivery. Shipping starts in October 2024.

If you missed the Kickstarter campaign or want to add books to your pledge or upgrade to a higher tier, the pre-order store is now open! The store is open to everyone, not just Kickstarter backers. I’m using Kickstarter pledges and pre-orders to set the size of the print run for later this year.

With more certainty on shipping costs, I added a new option in the pre-order store: a three-book bundle that combines a price discount on the book ($59, which is 10% off “list”) with a much lower per-book shipping price, particularly for delivery to Europe—the dollar difference between shipping about three pounds and 10 pounds is quite small!

(If you’d like to order more than a few copies for yourself or resale, please get in touch!)

Imagine Charlie Brown Snatching the Football Away

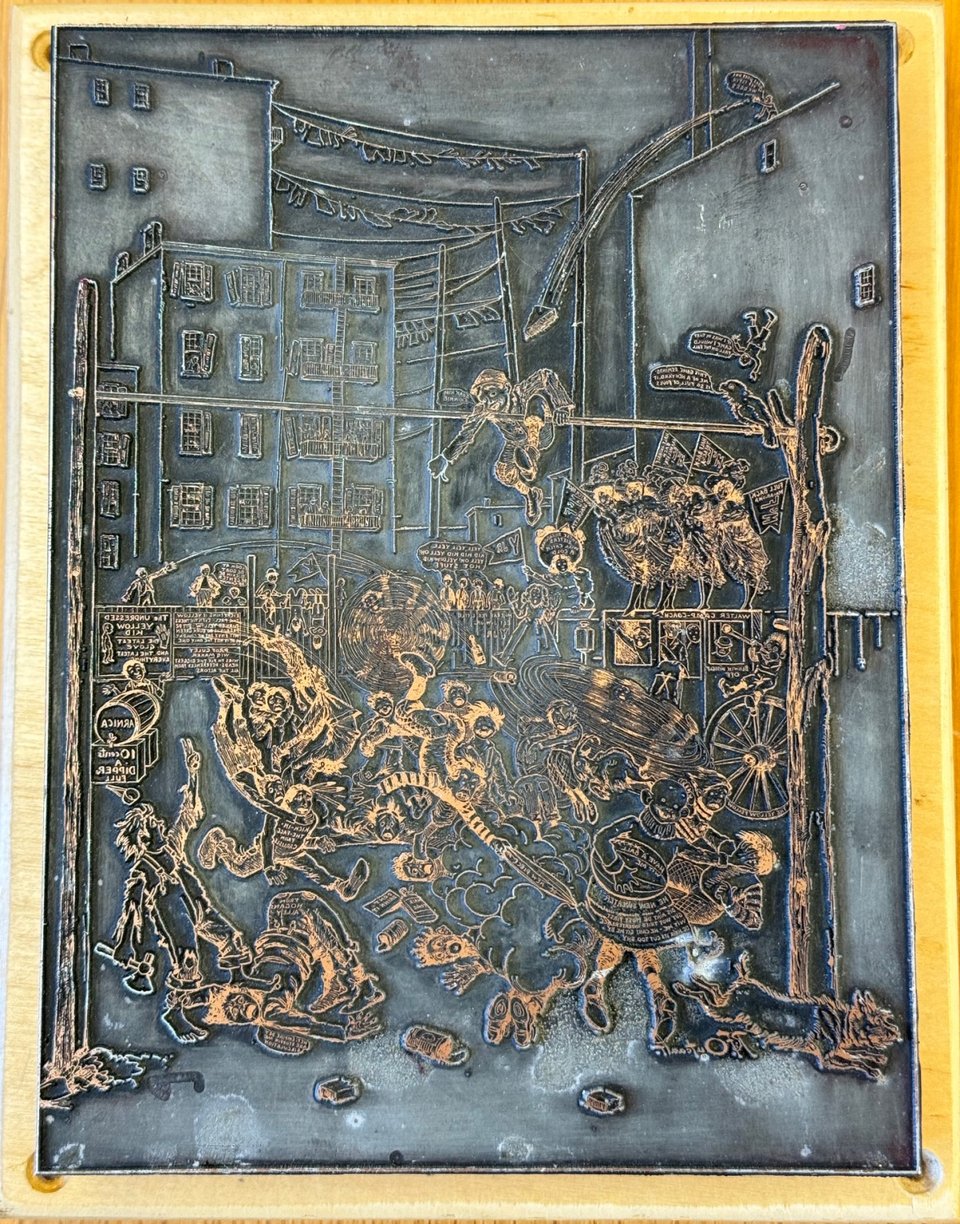

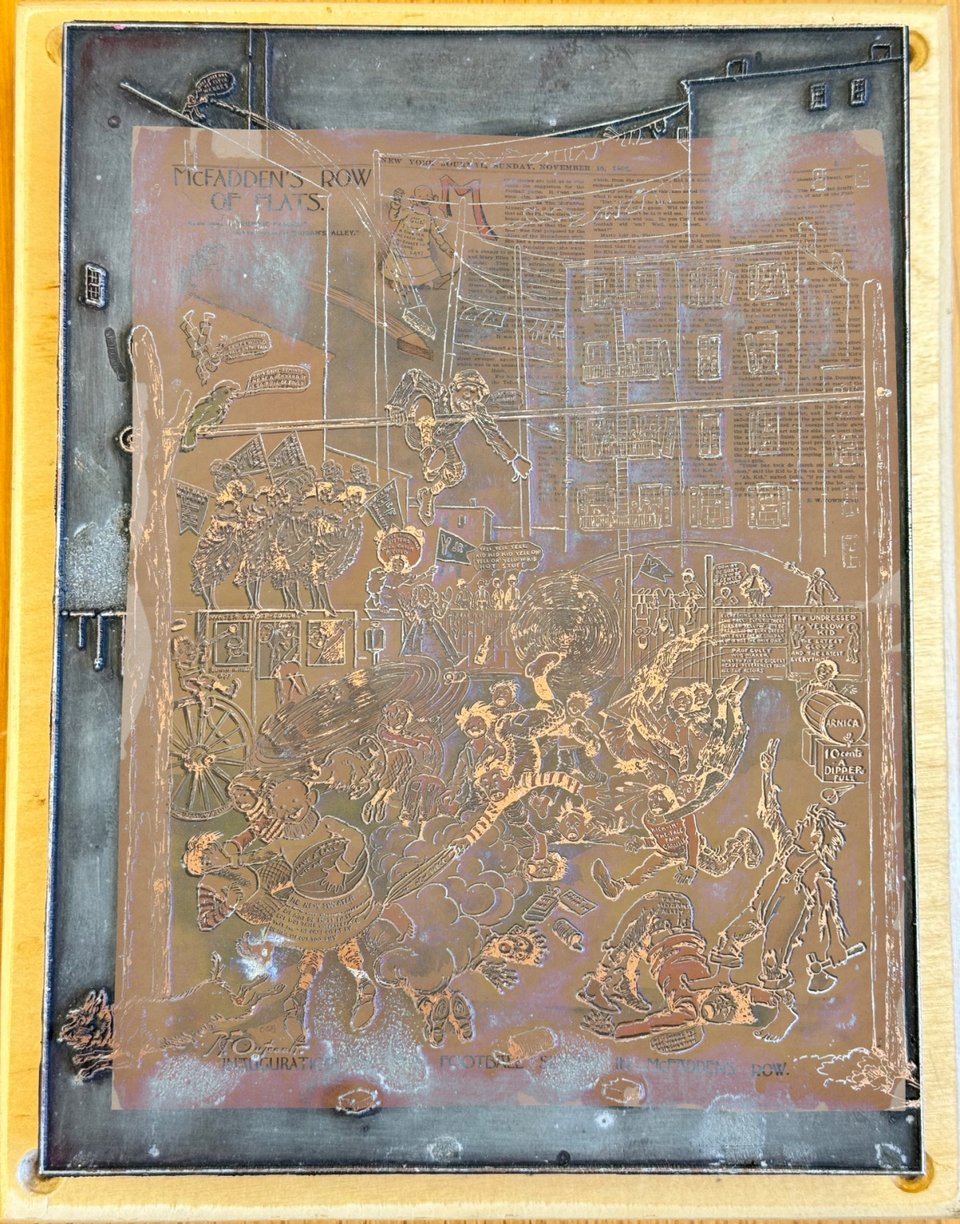

In 2023, the Billy Ireland Cartoon Library & Museum (BICLM, for short) at the Ohio State University acquired a remarkable 1896 comic metal printing plate featuring the well-known early newspaper cartoon “Yellow Kid” character running the ball in a mock football game. They asked for my opinion before purchasing it and, based on photos, I thought it looked both genuine and significant.

The Yellow Kid was an invention of Richard F. Outcault, an American newspaper cartoonist, whose work was among the earliest regularly appearing illustrations of the sort that resemble what we think of as comics today. Outcault created his shaved-head ragamuffin—shaved due to lice—in an oversized yellow shirt for a magazine in 1894. The character then appeared in cartoons for Joseph Pulitzer’s New York World in 1895 as part of the slice-of-life comic “Hogan’s Alley," depicting children in the Irish slums of Manhattan.

He took the Yellow Kid to William Randolph Hearst’s New York Journal in 1896 for a big raise, but due to a lack of certainty about ownership, the character also appeared in the World for about a year, drawn by George Luks. Outcault used various names for his comic at the Journal; it started as “McFadden’s Row of Flats,” which it was called through the period in which the BICLM plate was made.

BICLM has a micro-site on the Yellow Kid. Or consult Bill Blackbeard’s comprehensive out-of-print R.F. Outcault's the Yellow Kid: A Centennial Celebration of the Kid Who Started the Comics, available in paperback and hardcover from used bookstores and libraries. I’ll avoid digging too deeply into how the plate was made in this newsletter because of the technical detail—although I’ll provide a fully illustrated version in the book.

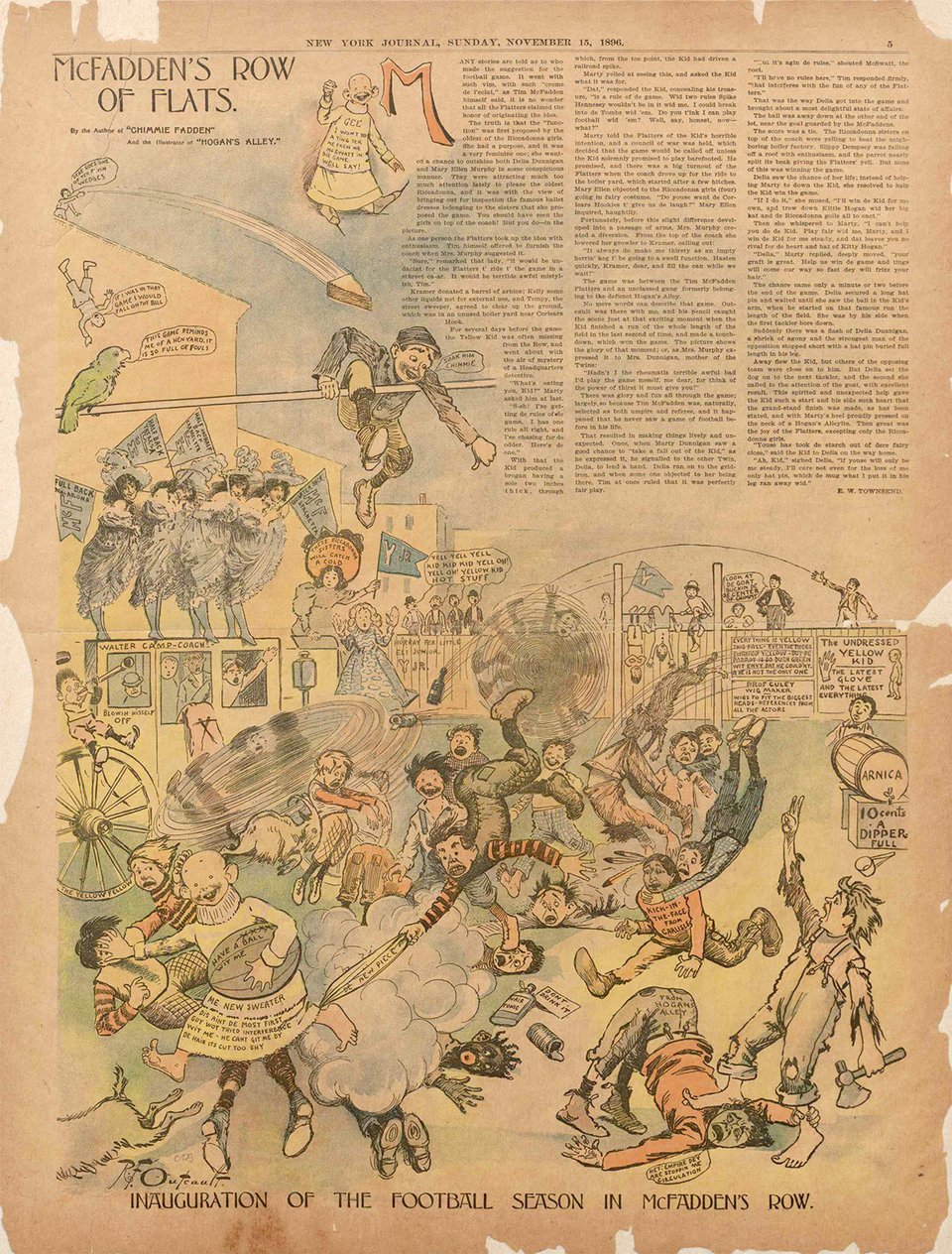

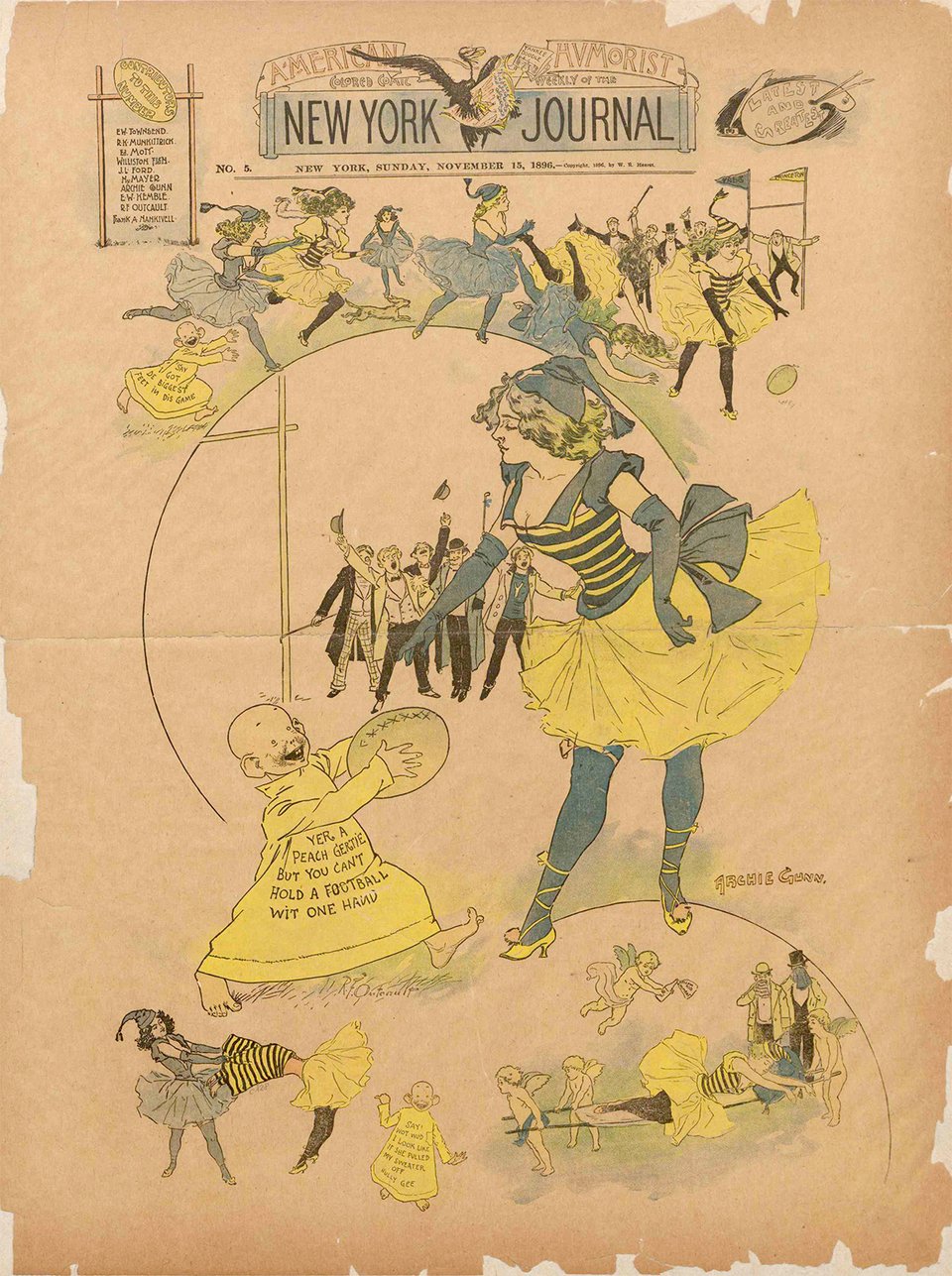

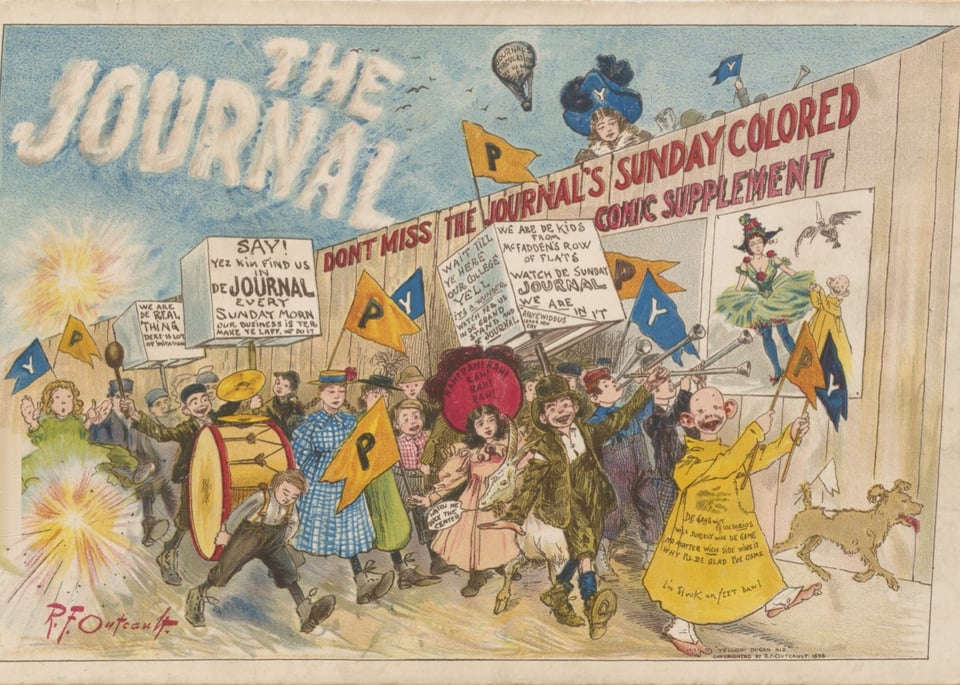

The BICLM plate matches the full-page cartoon that ran on 15 November 1896 in the Journal’s eight-page comics supplement, which was printed in black, blue, and yellow for more important pages (the cover, the center spread of page 4 and 5, and the back cover) and in black and yellow on the others (pages 2, 3, 6, and 7). The “McFadden’s Row” comic appears on page 5.

Please note the image features offensive stereotypical drawings of a Black person and a Native American person, using common depictions at the time. The Yellow Kid, incidentally, is Irish, not Asian—the “yellow” isn’t a stereotype about skin coloring but relates to the choice to print his shirt in vivid yellow.

The match they’re playing appears to reference an upcoming Princeton-Yale game on 21 November 1896 in the northern part of Manhattan (Manhattan Field, now long gone), despite both universities having their campuses a distance away by train. (Oddly enough, Boston MFA’s 1891 flong and plate are also of a Yale football game—that one with Harvard!)

The full-page cartoon is littered with references to Yale. This includes labeling a vehicle—probably a horse-drawn or steam multi-passenger coach—as the “Walter Camp Coach.” Walter Camp was an informal coach for the Yale football team, thus the pun in the label; he was also one of the most significant figures in defining American-style football as it split from a variation on rugby. The comic sports “Y” and “Y Jr.” on pennants throughout.

The cover also depicts a football game, this one played by artist Archie Gunn’s slightly risqué ladies, who appear in their typical tight tapered tops, skirts, and stockings. Outcault supplies his Yellow Kid in several places. Outcault and Gunn, being the two most-popular artists at the Journal, often drew their work side by side on covers and in promotions. The cover shows a Yale (blue) and Princeton (yellow) banner. While Yale’s school colors are blue, Princeton’s are orange and black—and you can’t make orange by mixing the yellow, blue, and black with which the page was printed.

Now, while the BICLM plate is a near-perfect match for what appears in the illustration, it’s a fraction of the size of the newspaper page—about half as tall and wide (25% of the area). It also contains details that were cut out of the newspaper version, including trees or poles on the left and right edges, the front half of a dog, and tenement buildings. A wedge-shaped piece of building material that’s thrown at the top has a different arc and location, too. The tenements and some other aspects were removed from the comic to include the fairly tedious storytelling in prose that accompanies the lively drawing.

I used Photoshop to overlay the plate on the version that appeared in print, distorting the plate to match the slight expansion and contraction that occurred in translating the drawing to print and the material changes over time in the newsprint and plate material. I also mirrored the plate, which is reversed for printing—it has to be mirrored or “wrong reading” in order to print “right reading.”

Due to luck and timing, I have had in my hands some of the earliest surviving plaster and paper printing molds and metal printing plates from c. 1805 and 1891 through visits to the Boston Museum of Fine Arts and the St Bride Printing Library and Stationers’ Company, both in London. Based on those items and other research, I believe this Yellow Kid marks the earliest known remaining example of a plate containing a cartoon. Boston’s MFA has what appears to be both the earliest wet-paper process mold (called a “wet flong”) and etched zinc metal plate of an illustration (1891) that survive. The wet flong process was in use from the late 1850s, so it’s a bit shocking to not have other examples; zinc photo-etching appears to have arrived by the mid-1880s. (The other only wet flong I know of is a text-only newspaper story from 1890 at Ball State University that’s a small portion of a newspaper page; the university seems to have removed its webpage listing the item, but sent me a photo last year.)

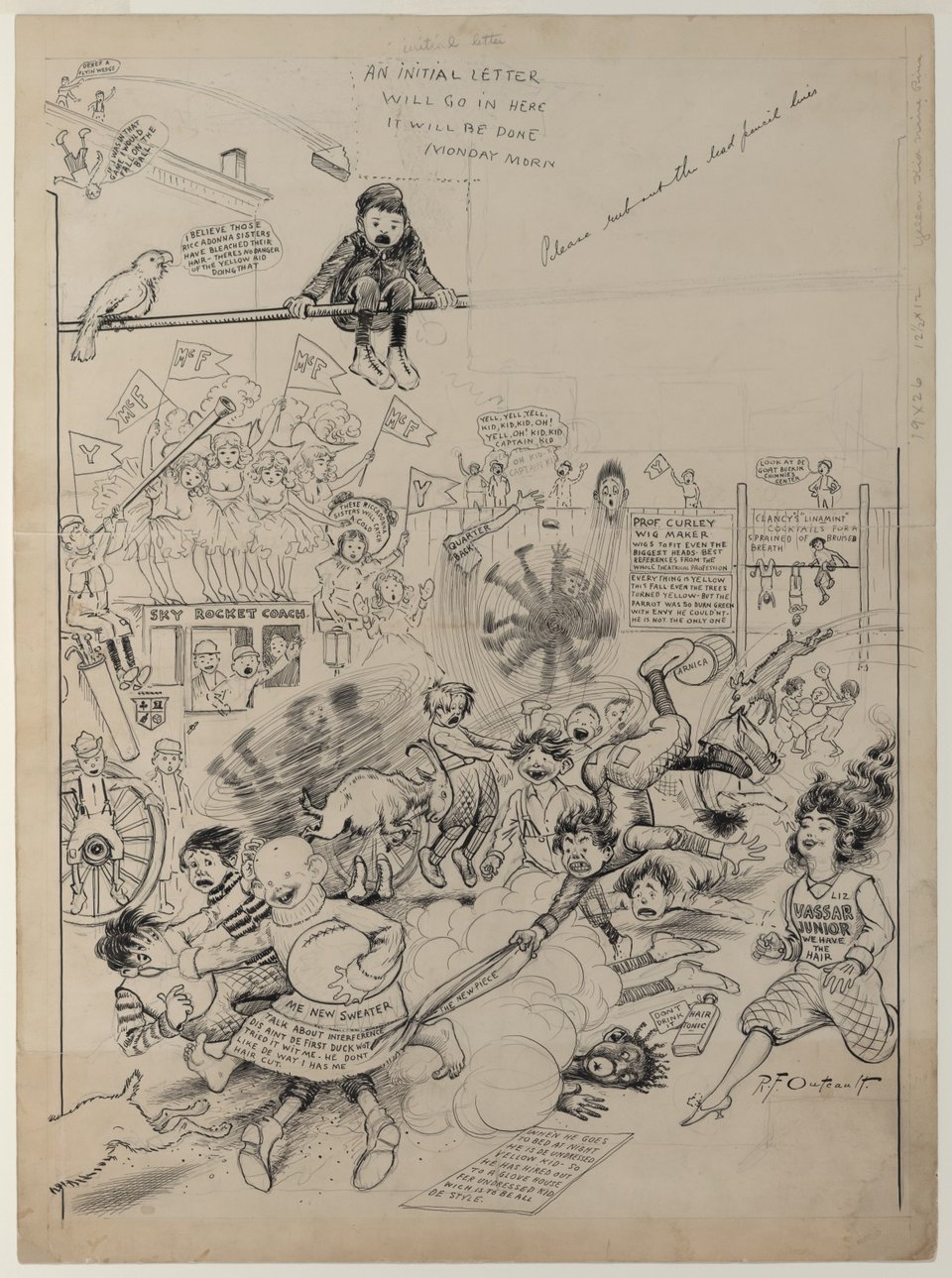

We can walk back a step in our study, because the mostly inked draft drawing of that comic is in the possession of the Library of Congress. Outcault clearly redrew it entirely. Note the four dancers (the Ricadonna sisters, who he had introduced not long before), who appear in a cartoony style sporting décolletage in the drawing, but in the final reproduction are depicted almost photo-realistically and covered up (but raising their skirts). This drawing omits the “Walter Camp Coach” joke and includes the Yellow Kid’s “girl,” Liz, at far right, where she is wearing a top that reads “Vassar Junior.” Yale and Princeton were men-only schools; Vassar, women-only.

The draft seems to have a finer style, with more detail and more expressiveness on the faces. Only part of that can be attributed to the difference between an inked drawing and a printed version: you can see an equal amount of detail, just not as artistically good in many cases, in the newsprint version and plate.

The comic and plate sparked all sorts of questions that I’ve researched both for my upcoming book and have summarized in a draft of a paper that I may publish separately:

Why was Outcault’s draft redrawn and with different elements for the final? A note on the draft suggests all that was left was an initial capital for “Monday morn[ing],” implying it was drawn at least seven days before the Sunday on which it ran. (Engravers might have needed as much as a full week to manage eight pages of comics that included color in those days.) Instead, he redrew it entirely with a similar composition.

Why is this plate—relative to the newspaper version—so small, lacks printed text, contains more detail, has no identifying information, and has a black border? I can’t find any instance of it appearing elsewhere at the time, nor why it would be reduced in size. This was before comics were widely syndicated using the “flong” molds, though some were distributed by creating duplicate metal plates. However, in that case, the plate would have the strip’s title, copyright information, and other details. (Outcault was careful to note his asserted, if not actual, ownership.)

The plate has a copper sheen and, by my visual analysis and research, I believe it was copper-plated (covered with a thin layer of copper through electro-deposition) to retain durability while printing or making duplicate molds. But there’s no trace of the wear I would expect from printing, even though some of the copper has worn off or faded.

Interestingly, I queried the Yale Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library about a program for the Yale-Princeton game of 1896 to see if the illustration appeared there. It did not—but the back cover was an Outcault-penned four-color advertisement for the Journal! Even with four colors, they still didn’t get the Princeton orange quite right.

Add a comment: