The Hand (and Mind) Is Where It All Begins

The Rich History of Printing Comic Strips

In 2017, I asked myself what I thought was a simple question after starting some research into printing history during my stint as the artist in residence at the School of Visual Concepts:

How were comics syndicated before they could be reproduced photographically?

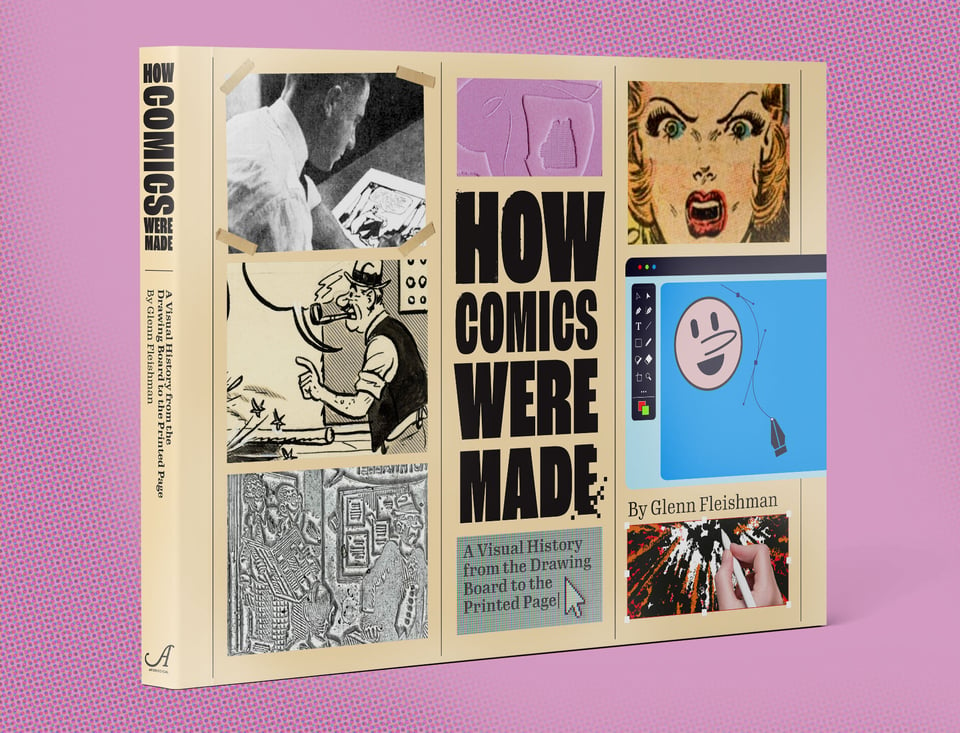

That question has led to six years of unceasing delight and almost zero frustration as I’ve answered the question for myself and others. I’ve expanded my remit, too, into the broader question posed and explained in my book project, How Comics Were Made:

How were comics reproduced, from an artist’s hand to the printed page across the modern history of newspaper comics?

In every era of comic strip reproduction, the answer varies a little. But there’s one thing that’s fundamentally the same: from the earliest days, at the start of the regular appearance of recognizable characters and strips in American newspapers from the Yellow Kid onward through this morning’s paper, email delivery, or web posting, it all starts with the cartoonist’s mind and hand. (AI-generated comics also start, uncredited, with cartoonists!)

My journey in the book is to show how artists were influenced by and interacted with production processes as those methods changed. What pen nib or line width or stippling technique or mechanical tint screen or drawing process did they use? Did they have inkers, engravers, colorists, and digital artists execute choices on their behalf? How big did cartoonists draw to get the advantage of reduction smoothing out wiggles—and how small did some choose to produce their work to keep more of the feeling of the hand there? How did digital color change the way comic strip producers, whether the creator or syndicate, conceive what was possible?

I’m excited to share all this with you—in words and many, many images—as my research continues and writing starts in earnest. I’ve been interviewing cartoonists, comics historians, and production people at a steady pace to gain insight from people who started working in the 1960s through the 2000s and even 2010s about their processes.

In installments of the newsletter, I’ll update you on book progress, include snippets from interviews, and share artifacts I’ve gathered. The crowdfunding campaign is currently on track for February 2024, and I’ll keep you updated about that, too. You can sign up for the announcement-only list I’ll use to send out just a handful of emails, notably when the crowdfunding campaign goes live—and how you can get in on an “early bird” reward in the first 48 hours. (I’ll also send out a newsletter about it!)

Let me know what you’re interested in! I have a lot of ideas for what to share with you all, but I’d love to know what intrigues, inspires, or mystifies people.

In this first newsletter, let me share a little of what I learned from an artist, originally underground, with now nearly 40 years of mainstream newspaper syndication under his belt: Bill Griffith.

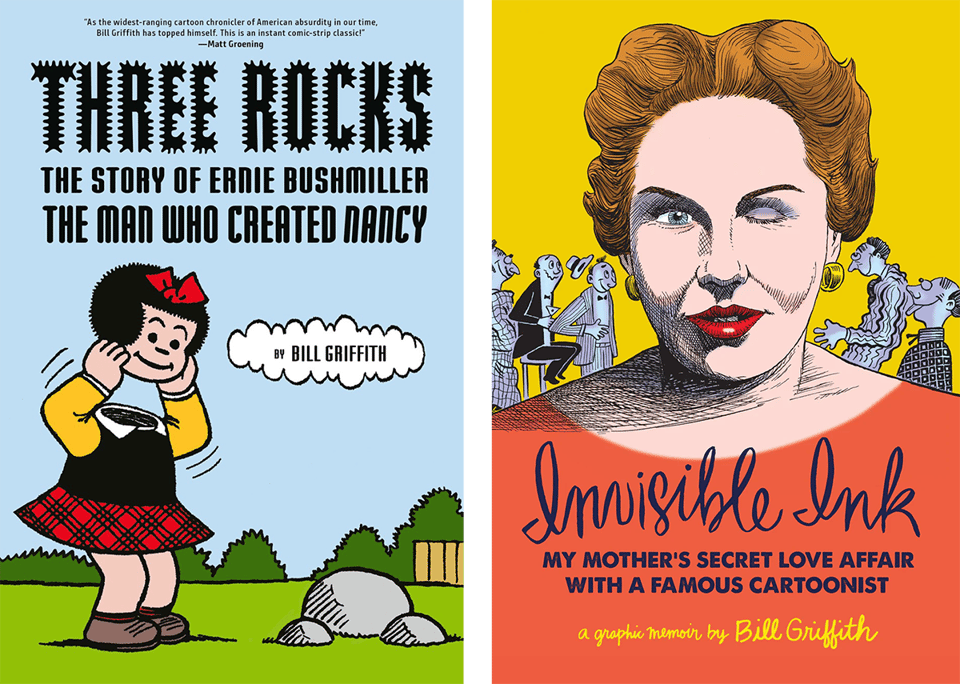

Zipatone the Pinhole

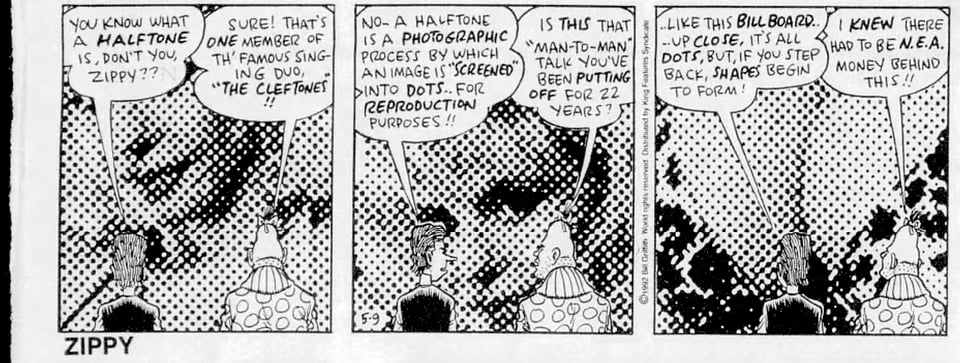

I had a great conversation spanning nearly two hours recently with Bill Griffith, the creator of Zippy the Pinhead, which is nearing about 40 years in regular syndication after appearing previously in a variety of underground comics and independently produced comics floppies and other forms. Bill’s biography in graphic form, Three Rocks: The Story of Ernie Bushmiller: The Man Who Created Nancy, offers a lot of interesting insight into a fascinating, quiet man who produced one of the most intriguing and commercially successful comics of all time. I highly recommend it, as well as Bill’s memoir focused on his mother, Invisible Ink: My Mother’s Secret Love Affair With a Famous Cartoonist. (Zippy the Pinhead’s name and Zipatone, an adhesive film used for shading in ads, comics, and illustrations, are unrelated, though Bill frequently used Zipatone to tint Zippy.)

Bill takes a great interest in the quality of his work and made the effort to learn quite a lot in the early days about what reproduces and what doesn’t. He says, “It’s been a long educational curve for me because I started out with absolutely no knowledge of how line art is reproduced. I just saw it reproduced. I just took it for face value. I came to comics through painting, not through the route that most cartoonists take.”

He drew his first comic for Screw magazine, a legendary “underground, sexually oriented newspaper,” as Bill describes it. (Steve Heller was the art director and has had an illustrious career since; I spoke to him last week for the book.) Bill says:

When I walked in with my half page, I measured the print size from a copy of Screw. I thought I would try to do a half page. And I brought it in, and Steve Heller said, “Oh, good, you drew it to the correct proportions. You’re the first to do that.” He said he was getting really tired of having to cut everybody’s art up or photostat them and then cut up the photostats to rearrange them in the correct proportions.

…I didn’t question my abilities, which were minimal at that point, because the transition from painting to pen and ink drawing—I had done pen and ink drawing, but not for reproduction and not for reduction….I only learned by doing. I literally learned the whole process of how line art gets reproduced by having it reproduced.

When Bill was researching Three Rocks, he purchased a scrapbook of “Nancy” comics, as he documents in the book. The anonymous strip clipper who put the collection together had arranged them thematically across long periods, which he found fascinating. But he had another reaction, too. Bill says:

I started looking. I said, “Oh, my God. You can actually see the indentation of the metal plate into the newsprint.” And if you really very lightly touch it, you can actually feel it. And then I realize what I’m looking at. I’m looking at art prints. These are the equivalent of lithographs or etchings.

A line drawing is created. The purpose for the line drawing is to end up reproduced, to end up being turned into a metal plate and the ink to roll over it, and then paper to roll over that. And then you get the final result. These are little works of art.

We talked about his experience in working close to reproduction, looking at the materials that were prepared for books and magazines, particularly in the era between metal and digital prepress (preparation for printing). In that period, a production person laying out material for an ad or a magazine or newspaper page, or a comics or layout artist putting together a page of a comic book created a layout that could involve elements drawn onto a sheet, photographed on a stat camera (a specialized enlargement/reduction camera that used high-contrast film to produce black-only output), typeset copy from a phototypesetter, and other material. Pieces that were cut out were held in place by rubber cement or wax.

Once a layout was complete, it was sent to the film department or a specialized service bureau. The layout would be placed in a vacuum frame and photographed onto high-contrast negative film under intense light. These negatives were then examined, touched up with opaquing fluid—a liquid that was painted on to blot out areas that shouldn’t print—or reshot, and prepared to be made into offset lithographic plates, another step involving high-wattage lights and photosensitive material, this time a paper or metal sheet that would be used on the press after being developed.

Bill remembers working closely with the negative during production in that era:

Before the books—my stuff—was printed, I asked to see the film negatives. I looked at the film negatives, and I could tell right away whether something—either because of under- or overexposure—something was clogging, because I had the originals to look at right next to it. So I would find a little tiny spot on a page that had delicate cross-hatching. And I would look to see if there’s a little white dot in the middle of all the cross-hatching. Cross-hatching leaves a little white section in the middle of all the hatching. So you pick one that’s really tiny on the original and go look at it on the neg. And if it’s on the neg, that means the neg is good all over. There’s no need to look any further.

So I would always ask to look at the negatives, and I would have, in some cases, I had opaqueing with a brush. I would fix things sometime. Once in a while, I would scratch a negative to fix it rather than redo it, because it was a tiny little problem. And I’m sure I was a pain in the ass to these people, but I wasn’t the only one. I did it also when Art Spiegelman and I edited Arcade, until he left in the middle of that and went back to New York. But for the first three or four issues, I did that for everybody else’s work, not just mine. So I looked at all the film negatives and made sure that they were as good as they could be. And sometimes it didn’t work. Sometimes something went through. But these days, that never happens—just never, ever happens.

(That little white or transparent dot on a negative is sometimes called a pinhole, if you wondered for the last many paragraphs about my pun in this interview heading.)

Share the word

If you know folks interested in comics history you think might find my book an interesting journey, please direct them to the How Comics Were Made preview website, where they can sign up for this newsletter (or via this link) or the announcement-only list for when the book starts its crowdfunding campaign and later goes on pre-order and direct sale.

Thank you!

—Glenn

Add a comment: