Sluggo Is Lit…erature

In this issue:

An update on How Comics Were Made

The oldest comic flong

Nancy Fest: take a bow

Roughly Speaking, Nearly Done

The rough draft and layout of How Comics Were Made are nearly complete and we’ll soon be moving into editing, proofreading, and the final design. My collaborator on this project, designer and illustrator Mark Kaufman, has been a great partner as we hash out chapter lengths, graphical approaches, and storytelling. He has a marvelous sense of rhythm and visual punctuation. Every time I receive design updates from him, I’m delighted to see where he found elements to emphasize and amplify that provide more breadcrumbs for the historical and technical narrative.

The book can be pre-ordered through late summer, and several higher-tier unique items and benefits—including one-of-a-kind “Peanuts” Sunday molds and you being drawn into the book—remain available.

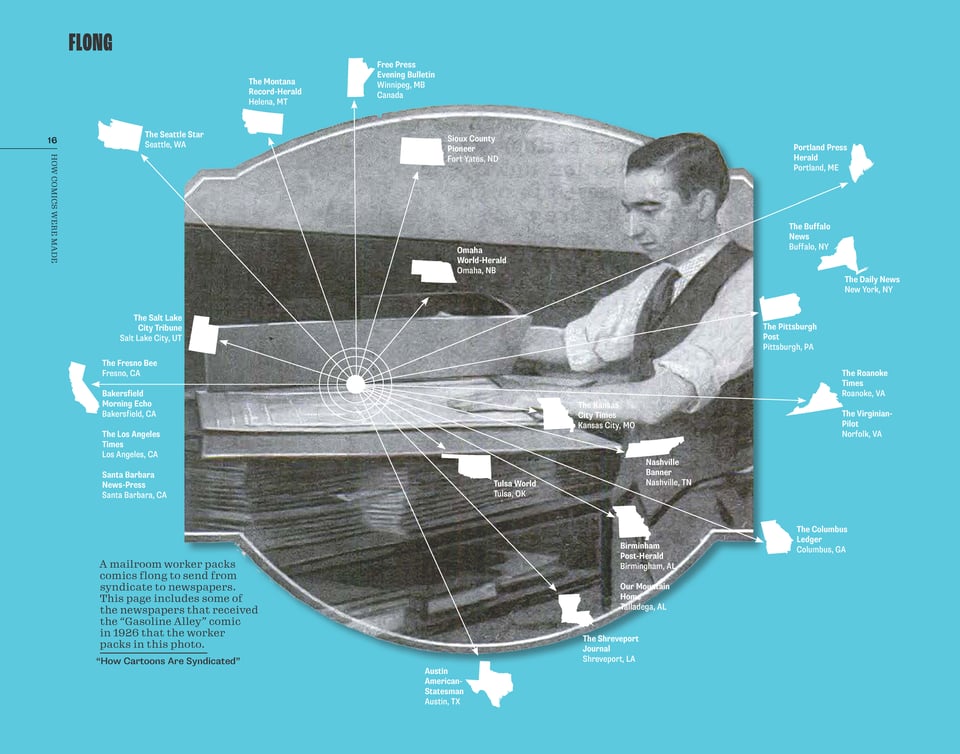

When we were building the preview chapter, “Syndication in Metal,” for the Kickstarter campaign, Mark had the idea of plotting against a map the stage where comic molds (flongs) were packaged and shipped to newspapers. I researched which newspapers carried “Gasoline Alley” at the time of the photo of that strip being packaged, and those are what appears on that page.

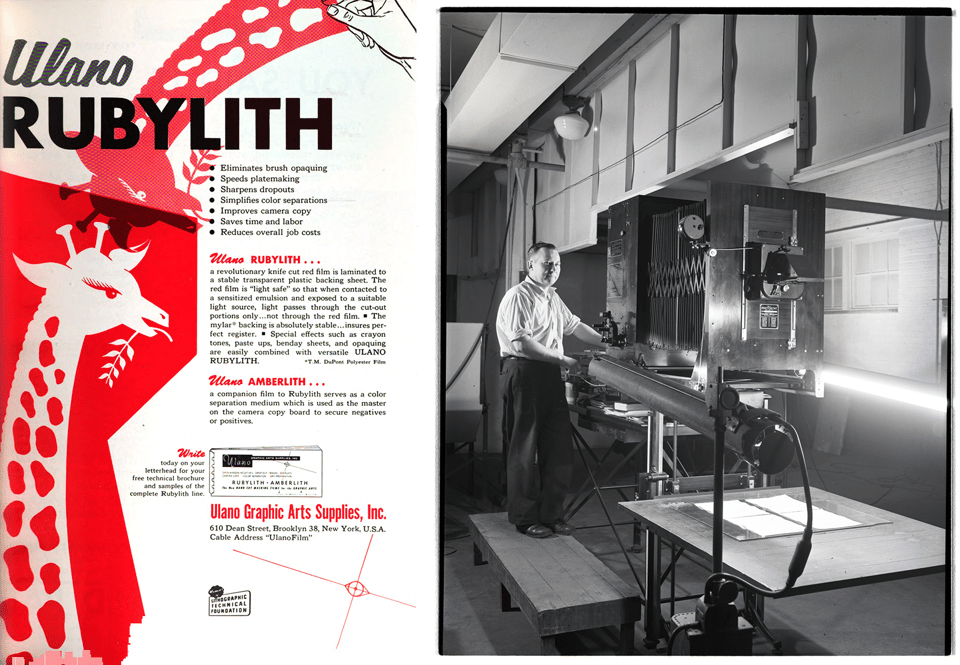

One of the most time-consuming and exciting parts of the book is sourcing images: photos, illustrations, technical drawings, and cartoons. Part of our design-roughing process is that I take my written draft and insert all the figure references and captions for Mark in the order they should appear. Sometimes, I’m mocking up a very loose preview as well to give Mark guidance about the relative importance of images and their placement. In writing and revising, I’ll be tooling along and pulling out images I’ve scanned, photographed, requested from institutions, retrieved online (for public domain work), or licensed, and I hit the brakes—I don’t have something that illustrates this important point at all! That can lead to 20 minutes or 2 hours of work to track down the right example that I can also ultimately both obtain in high resolution and have permission to reproduce (if not in the public domain*).

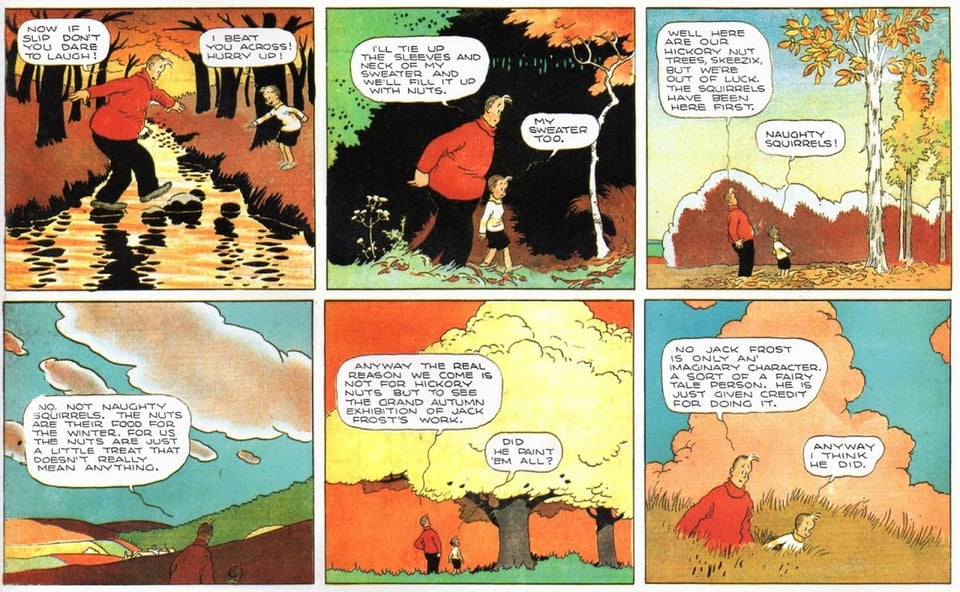

A great example: at Nancy Fest on May 24–25 at the Billy Ireland Cartoon Library and Museum at the Ohio State University (more on that below), talking with comics aficionados, two different people told me to go look at a full-page “Gasoline Alley” Sunday newspaper framed in the permanent exhibition at the library. I remembered late on the last day to seek it out—and it’s extraordinary. In 1928, cartoonist Frank King, in cooperation with the colorist and syndicate engravers, produced a remarkable set of tones and gradations that the newspaper that printed it managed to capture as well. A real work of art, made even more incredible given the hard work in 1928 of essentially painting dots by burnishing an inked screen—the Ben Day process, which gets its own chapter in my book.

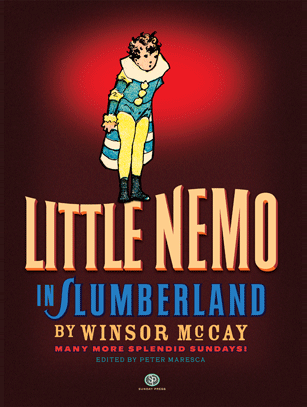

This comic will fit nicely in the book to illustrate both what Ben Day artists could achieve and how newspapers could print beautifully at times. Digging around to find the source, I spotted that the strip appeared in a collection from Sunday Press. Publisher Peter Maresca was at Nancy Fest—I had previously interviewed him for the book, and he had offered scans of public-domain work for anything he had, and 1928 is the current leading edge of the public domain in America.* Bingo! I’ll be working with him to get a reproduction-quality image.

To fill some gaps, I have just hired an artist to create a few illustrations for two sections of the book where no clear photographs or images exist of the steps involved in parts of print production used in producing the color plates for Sunday comics. That will definitely help for clarity, and it’s great to bring another craftsperson into the mix.

*Copyright law, particularly around the public domain, is a hole without a bottom. However, there is one simple case: all work published in the United States before 1978 enters the public domain after 95 years on the following January 1. (The easy formula is “copyright year plus 96” to get you into the correct following calendar year.) As of January 1, 2024, that includes all work published through the end of 1928. Many works published after 1928 through February 28, 1978, also entered the public domain for other reasons. While I’m licensing a lot of material for my book, the role of the public domain has been huge for historical resources, particularly when the business that held the copyright shut down 60 or 70 years ago!

The Oldest Comics Flong

I have a number of searches saved at eBay, and every day I receive several emails with the results of them, which should only include new items—the system isn’t perfect. But it’s helped me stay abreast of new artifacts as they enter the market. Most of my personal collection has come from eBay, with some notable exceptions, such as 200 “Peanuts” Sunday color-separated mats/flongs.

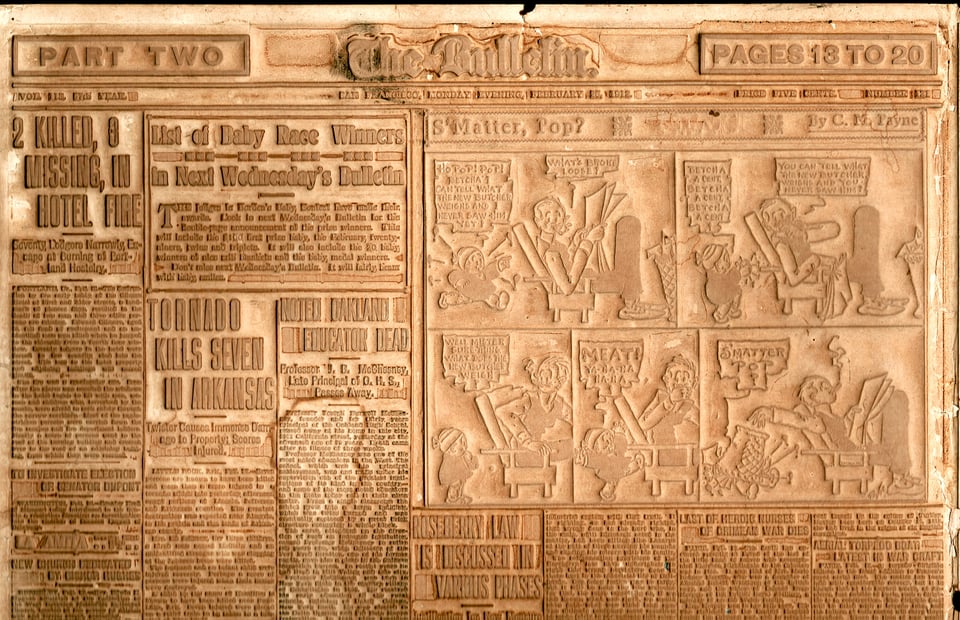

The other day, I noticed some full-page newspaper molds from 1911 and 1912 of the San Francisco Bulletin, a paper I didn’t know existed. I spotted on one of the several pages a comic on the front page of a section. This was exciting, as it was a weekday edition and the comic was in panel format—an actual strip, not the set of sketches that were common as daily cartoons into the 1910s and beyond. I negotiated the price and acquired the whole set, interesting in its own right, but remarkable for that comic strip.

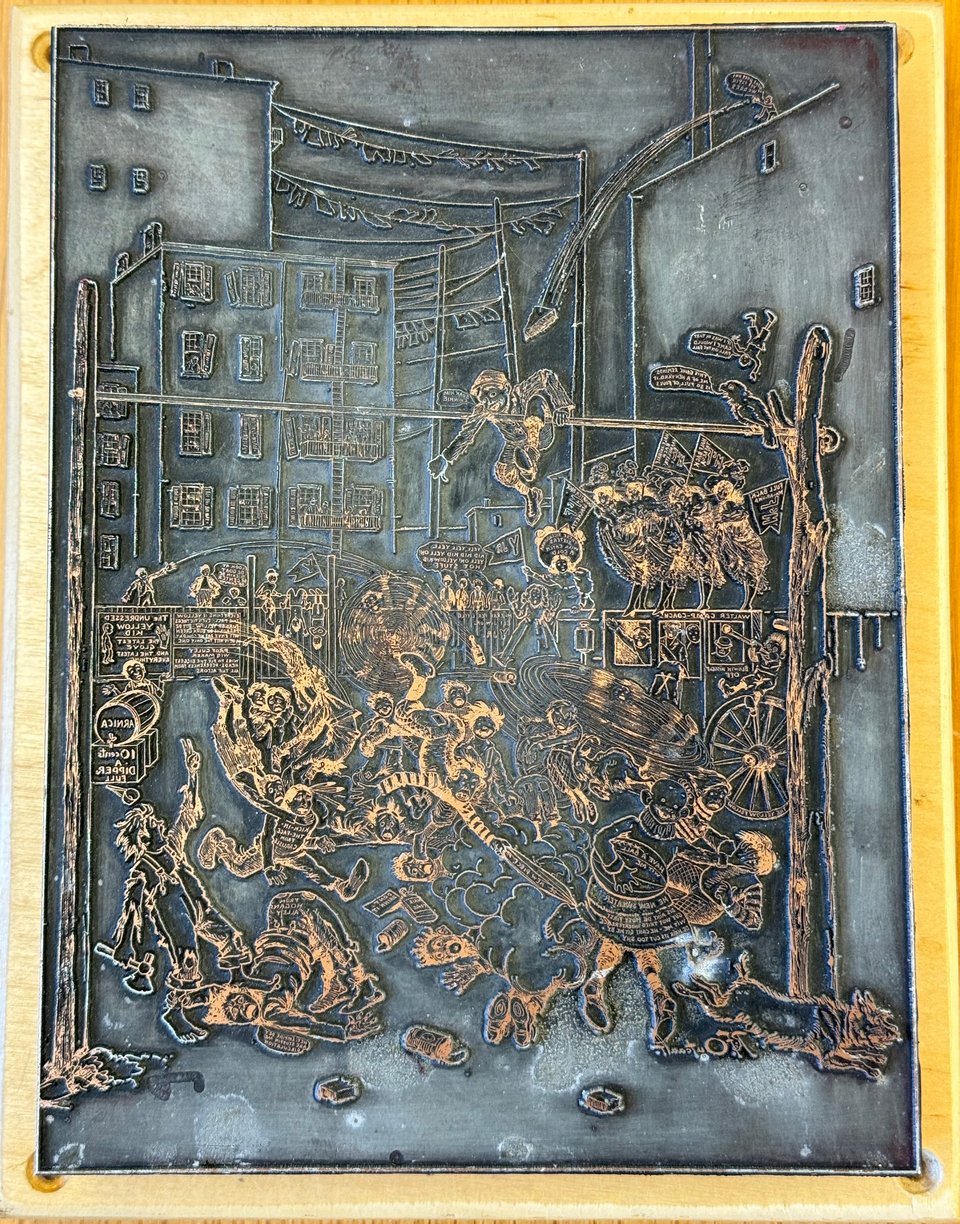

I believe this comic flong is the oldest known surviving comic mold of any kind. The strip is “S’Matter, Pop?”, one that I had never heard of before. Benjamin Clark, the curator of the Charles M. Schulz Museum and Research Center, said that Schulz referred to it as his favorite comic. Born in 1922, he could have read it through childhood into his teen years, as it ran from 1910 (as “Nippy’s Pop” for one year) through 1940. (This is an early example of national comics syndication, too, as “S’Matter Pop” appeared coast-to-coast, but in checking digitized papers, the same episode didn’t appear in sync across publications.)

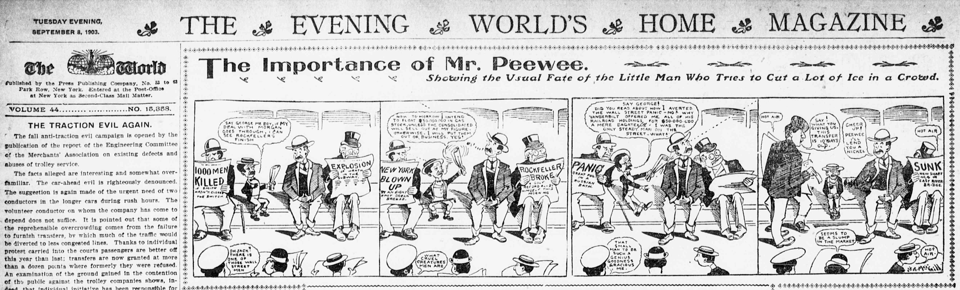

This installment appears in the Bulletin just five years after the first “Mutt and Jeff” by Bud Fisher (1885–1954) in 1907, long thought to be the first recurring daily comic strip. It debuted in black-ink only starting November 15, 1907, with just a Mister “A. Mutt”—Jeff arrived in 1908 and the joint title in 1914 or 1915, but Mutt appeared consistently from day one. However, comic historian Allan Holtz discovered in 2004 in Hogan’s Alley (issue #12) that an earlier strip should get the title: “The Importance of Mr. Peewee” meets the definition of a comic strip in every way in its continuous run (across three artists) from September 9, 1903, to at least September 23, 1904.

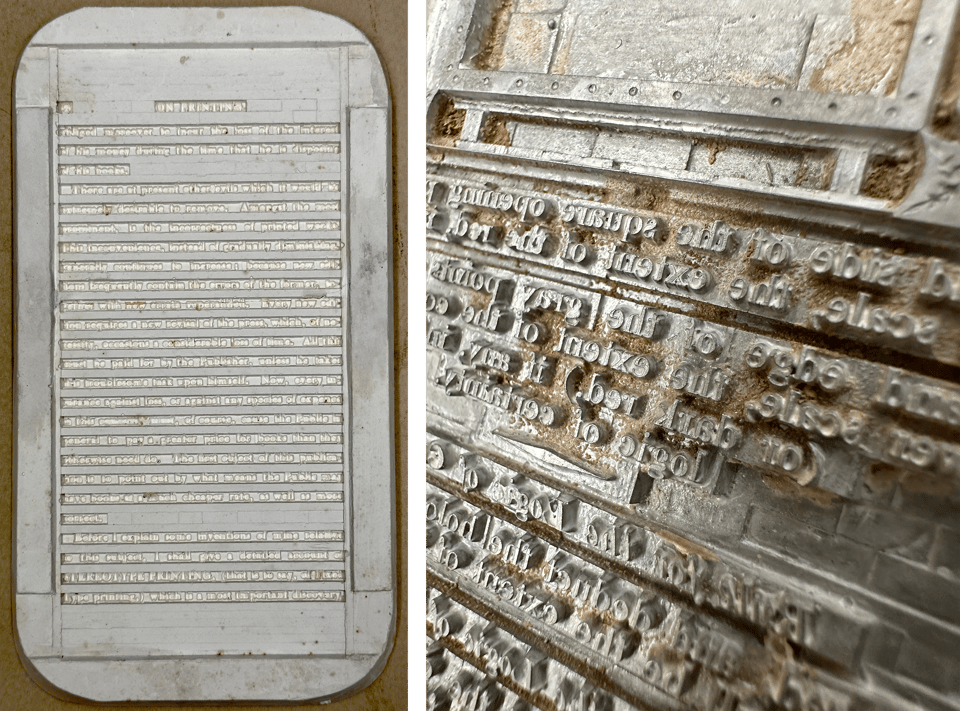

My research into printing plates and molds is what brought me to the current comics history project, and I’ve put in hundreds of hours at this point trying to find the oldest examples of every version of what’s called the stereotype process, as the plates were dubbed “stereotypes” (durable impressions, from Greek roots) in the late 1700s. The molds didn’t get the flong moniker until no later than the 1860s. (This research developed into a chapter of Printing Things: Blocks, Plates, and Other Things That Printed, edited by Elizabeth Savage and Femke Speelberg [Proceedings of the British Academy with Oxford University Press, forthcoming 2025].)

I’ve visited the Stationers Company in London (while on vacation in June) to see a circa 1805 plaster mold made by Charles Mahon, 3rd Earl Stanhope (1753–1816). Earl Stanhope perfected a process that had only existed previously in fits and starts, and, with Andrew Wilson (?–?), his business partner and printing plant manager, turned into a commercial production process. On that visit, I also examined plates made from that process held at the Stationers Company and, from the same batch rediscovered in 1989, at the St. Bride Printing Library on Fleet Street.

Last July, I also passed through Boston and was able to take a long, close look at an 1891 illustration flong of a Yale-Harvard football game preserved along with other component pieces at the Museum of Fine Art. A curator there had attended a Zoom brown bag I did for my mentor at the University of London on flong, and invited me to see it. It’s the oldest paper-based flong of an illustration, and I’m including a photo of it in the book. (There’s an 1890 flong of a couple of columns of text from an English paper that is in the Ball State University collection, and which I haven’t seen in person.)

Then, in a research trip to the Billy Ireland last December, they let me handle an 1896 printing plate with an image of a Yellow Kid comic on it, which will take up a whole chapter in How Comics Were Made, and which I wrote about in a previous installment of this newsletter. I believe this is oldest comics plate that’s been found so far. Oddly, that Yellow Kid features a parody of a Yale football game, too! This one against Princeton.

When this book project is over, I’ll donate my comics printing artifacts, including the oldest comics flong, to the Billy, having photographed/scanned and completed all my firsthand studies.

Nancy Fest: Take a Bow

I spent about 40 hours in Columbus, Ohio, the weekend of May 24–26 for Nancy Fest, a celebration of the “Nancy” comic and its primary creator across 57 years, Ernie Bushmiller. Put together by the aforementioned Billy Ireland, the event was also the public opening of a major exhibition devoted to the strip, “The Nancy Show: Bushmiller and Beyond,” curated by Brian Walker. A fest? A show?? For Nancy??? Why?????? [Visualize sweat and anxiety lines radiating off my head here.]

Some people think the comic strip “Nancy” is the least funny thing they ever read. For them, it takes the “comic” part of “comics” out of the equation. For many others—based on the continued popularity of old and new strips—it has a particular kind of humor coupled with superb drawing and writing that elevates it from the realm of the rest of the funnies into something higher. Still goofy, still corny, still ostensibly about a kid—but, for some, the best comic strip ever created and one unlikely to be topped.

This admiration of Ernie Bushmiller has only grown since his death in 1982, with several books devoted to reprints, analysis, and biography. Bushmiller didn’t exactly originate the strip. He took over the comic “Fritzi Ritz” in 1925, three years into its run when that cartoon’s creator moved on. Fritzi was a pin-up girl, va-va-vooming her way in moving pictures. That wasn’t really Bushmiller’s style. Nancy was introduced as Fritzi’s niece in 1933, and, like kids, cats, and Urkel are wont to do, she quickly took over. In 1938, the strip was renamed for her.

It’s hard to imagine this era, but it was a time when readers of comic strips wrote letters to their newspaper or the national syndicate in the hundreds or even thousands each week. When Nancy appeared, the sentiment was apparently huge, and the syndicate urged Bushmiller to add more Nancy!

Cartoonists produced some of the most profitable parts of newspapers on a size-to-reader-value ratio and were paid absurd amounts. With about 2,500 daily papers in the United States—sometimes 10 in one city—a popular cartoonist could be in 800, one in each exclusive market, and make the equivalent of millions of dollars a year just from their split of syndication revenue. Add millions more for animation, merchandise, books, and other spinoff and related products. Bushmiller’s lifetime income isn’t known, but he would have been making as much money in his day as bankers and minor oil barons—or, today, a popular YouTube video creator.

Bushmiller was appreciated by his fellow cartoonists during his lifetime and had a mixed amount of critical respect. Some dismissed him, often with contempt. But the graphical example for a comic strip chosen by the American Heritage Dictionary for its 1973 edition was “Nancy.” With few words and an economy of lines and images, that strip and thousands of others in his most fertile and precise period, tell a story you perceive almost before you realize you’re reading it.

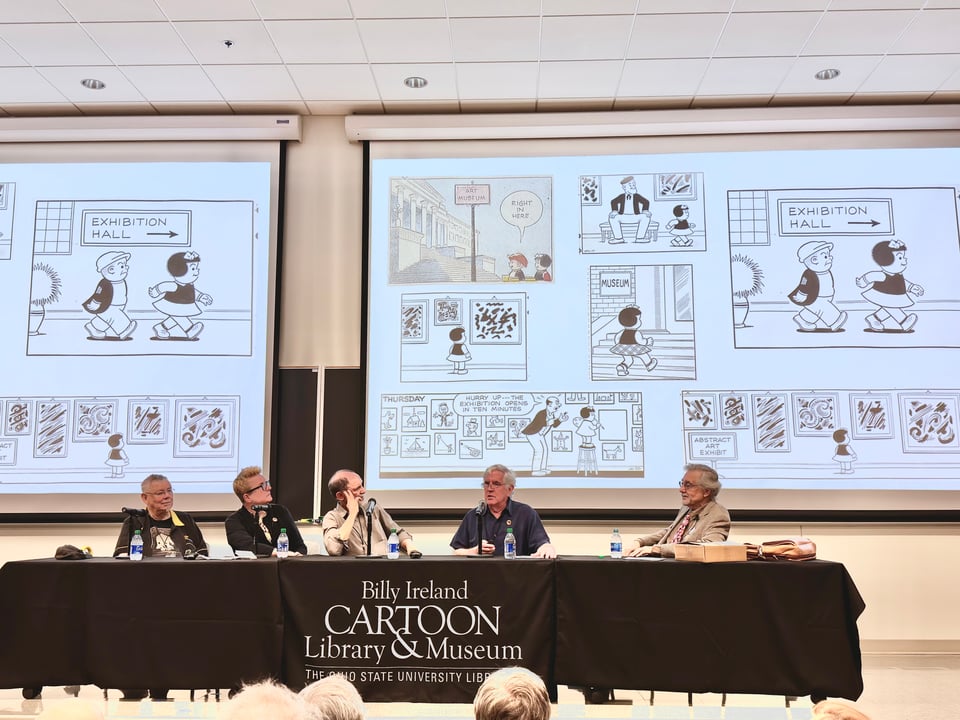

Nancy Fest offered up the greatest “Nancy” experts in the world to talk about why Bushmiller’s work was both so loved and so closely studied. Authors of several books spoke, as well as a panel of cartoonists and publishers who had done “Nancy” collections, tributes, parodies, and paintings over their careers. It was hilarious, profane, insightful, and often absurd. But fun, end to end.

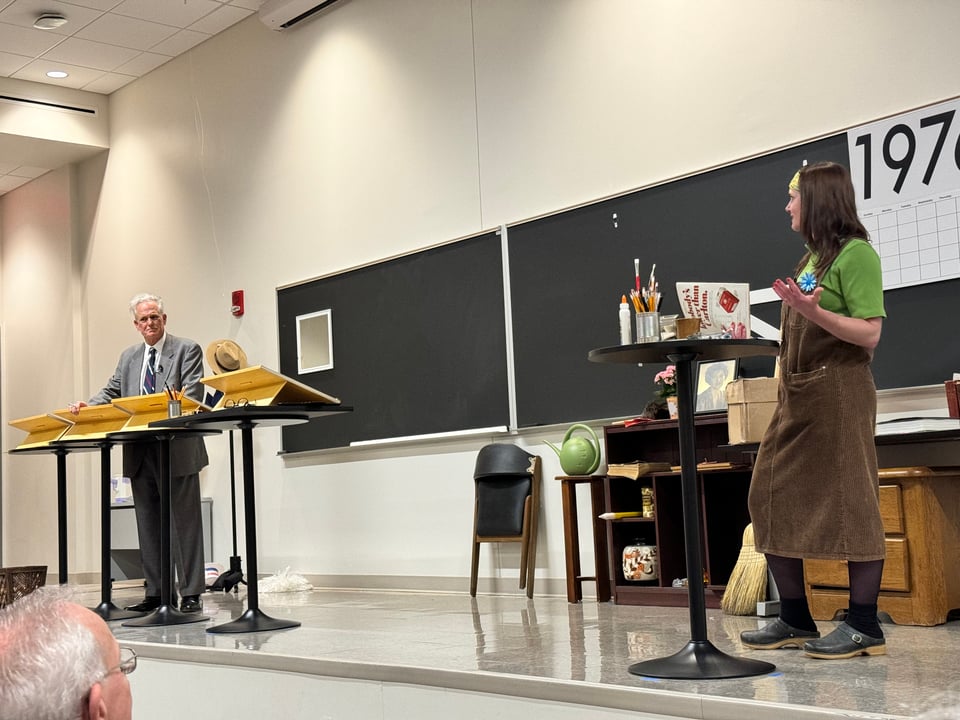

An especially remarkable coda was Saturday Night Live, Seinfeld, and Simpsons writer Tom Gammill’s play, A Morning with Ernie Bushmiller, which co-starred Billy Ireland curator Caitlin McGurk in a number of roles. Gammill is the premier collector of Bushmiller originals, and a sizable portion of the exhibition—curated by Brian Walker—comes from his collection. (Brian’s son, David, is making a “Nancy” documentary and was filming throughout the festival.) Gammill played the role of Bushmiller, talked about that man’s history first person, illustrated jokes with “Nancy” panels flashed onto a projection screen, and sang songs he’d written, including an audience sing-along about what would have happened to Charles Schulz if Bushmiller had named his Sluggo character “Snoopy.”

The main body of the museum exhibition is dedicated to Bushmiller’s period; the smaller but still sizable second gallery focused on work about “Nancy” and on its continuation. After Bushmiller’s death, “Nancy” was drawn by several other artists, the current being Olivia Jaimes, who announced during Nancy Fest—in a hilarious and thoughtful prerecorded presentation voiced by someone else—a leave of absence during which time other cartoonists will guest star. Owned by the syndicate, it will never end until it ceases to be read widely enough. (The presentation was “watch once and delete”: it was not recorded by the museum, the audience was firmly told not to record, and Jaimes asked the organizers to delete it immediately after playing.)

While attending a comics festival in the middle of trying to finish the main part of How Comics Were Made might seem like a lark—and it was awfully fun—I managed to get answers to several dangling questions for my book by examining original and printed strips in the galleries and talking to a variety of folks, like Bill Griffith (whom I’d visited in Connecticut back in April), Derf Backderf (who tipped me to “lithographic crayons”), and Mark Newgarten (cartoonist, educator, and co-author of How to Read Nancy).

And now…back to finishing my book!

Add a comment: