Ink-a Dink-a Do

When I was researching How Comics Were Made, one of my keenest interests was untangling the development of color in comics because it is a relatively unexplored topic. A lot of focus was put on whether the Yellow Kid was the result of determining how to get an effective yellow pigment that could hold and dry quickly when inked onto newsprint. Bill Blackbeard—among others—has disputed the hoary story told later that the Yellow Kid was the result of mastering yellow.

Read more about coloring the comics below after a brief update on the upcoming availability of a new printing!

How To Pre-Order How Comics Are Made

The new edition of my book, now titled How Comics Are Made, is coming soon from Andrews McMeel Publishing! The new version is hardcover with a dust jacket and retails at a list price of $40. That price appears to hold worldwide, more or less, with currency conversions. I created a list of pre-order links at the book’s website for bookstores around the world, including both small operations (such as stores around my hometown of Seattle) and big chains/online retailers.

The book’s North American release date is June 3, 2025, and many other countries also list availability on that date; a few stores in some countries are showing July. You should also be able to walk into your favorite bookstore on June 3rd or later and find it on the shelf or ask them to order a copy.

The Andrews McMeel edition is very similar to the version I produced in 2024. There’s a single Sunday comic I swapped for a better one and some very minor changes (mostly small typo fixes) in the text. I’ve published a list of errata discovered so far on an updates page.

I received an advance copy a few days ago, and you can watch a quick “unboxing” video on YouTube.

The new edition of the book was printed in China, so you would expect tariffs would affect its price. Fortunately (for the entire U.S. publishing industry), it appears that because the tariff authority the U.S. administration is employing comes from a 1977 law that exempts books and other “informational materials,” book imports are unaffected. Whew!

If you’re interested in the history of printing in general, you might want to get a copy of the new edition of Six Centuries of Type & Printing, now in crowdfunding. Use this special link to get 10% off ($29 instead of $32) the basic ebook/print bundle reward.

How Comics Got Their Color

The results of my color research may have revealed some contemporary sources Bill Blackbeard didn’t have access to before mass digitization. American Printer and Inland Printer were two key U.S.-based trade journals that promoted new technologies to printers, demonstrated printing techniques in their pages, editorialized on technology and industry, and—most importantly to a historian—answered questions from people working in the field.

Printing inks require a lot of different properties to work, particularly in the 1890s, when multi-color presses were being invented and rebuilt seemingly every few weeks. To print multiple colors, the non-black inks must have a strong pigment yet be translucent in relationship to other non-black colors, have the right “tack” (a form of adhesion) so that a subsequent ink doesn’t rip off the one beneath as the paper passes through a plate, and dry quickly to prevent smearing as pages whizz through a press and into folding and binding. (Tack is what happens when you put your finger on wet paint and some it rises as you pull away.)

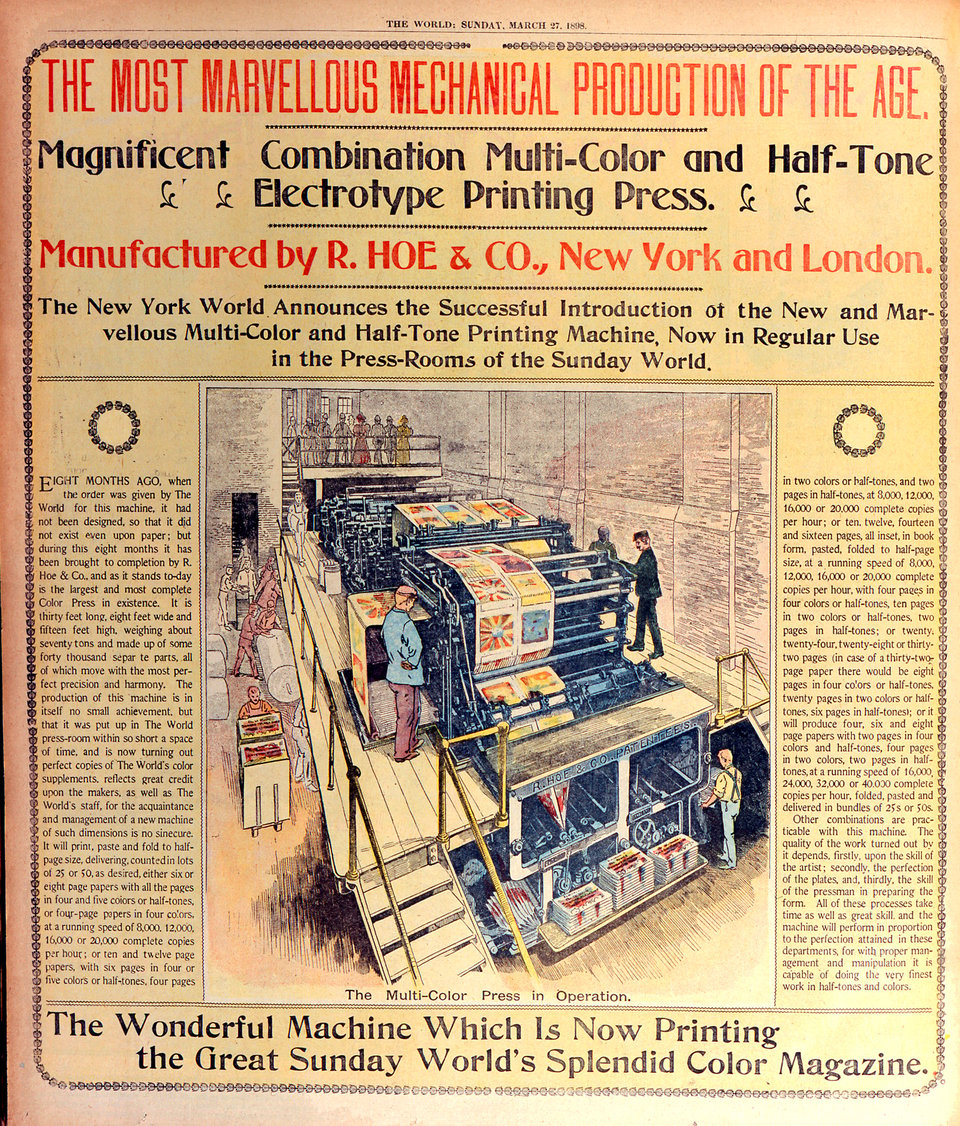

In 1892, the Chicago newspaper Inter-Ocean imported a multi-color press and printed illustrations that combined colors; in 1893, they added comics. The New York World had its color press running later that year and offered a comics supplement. But it was still early days. I quote William J. Kelly from The Inland Printer’s September 1893 issue in the book:

The making of colored inks that will distribute freely, cover solidly, and leave the face of the printing plates clear at the high rate of speed employed in color-newspaper printing is a problem that has as yet been but partly solved.

By 1896, when the Yellow Kid first appears with a yellow shirt and that metaphorically sticks, the color problem had apparently been fully overcome. By 1898, the Typographical Journal, another industry publication, raved:

Color printing on fast presses has been revolutionized by the wonderful work done by the New York Journal in its Christmas supplement. Rarely in lithographic work has anything so beautiful been accomplished, and it seems now that the art of color printing for newspapers is in the class of the most carefully printed lithographs.

That was as far into the weeds as I got in the book, but there’s a whole subject area I hope to explore more in future writing and potentially a future edition of the book if I can add a chapter on the topic. The question is: What colors did they use?

In the book, I noted a few places that four-color printing, or process-color printing, designed to reproduce a full range of colors for illustrations or photographs, are cyan, magenta, yellow, and black in modern times—CMYK, where black is K for the key or aligning color. However, at the outset of four-color printing, the paler magenta and cyan were either called red and blue or actually printed in a more solid red or blue pigment.

As the 1918 book Printing Inks explained:

Process inks are made in four colors: Yellow, red, blue, and black. Most ink houses make several yellows, varying from a greenish yellow to a chrome; several reds, from a pink to a bluish red; and several blues, from a peacock to a dark blue. These varieties are to meet the demand of the engravers who seem to have different standards of colors. With these colors almost any result can be obtained. The greens and purples in a picture are affected most because it is difficult to get a fine green by the use of yellow and blue. It is also difficult to get a good purple by the use of red and blue.

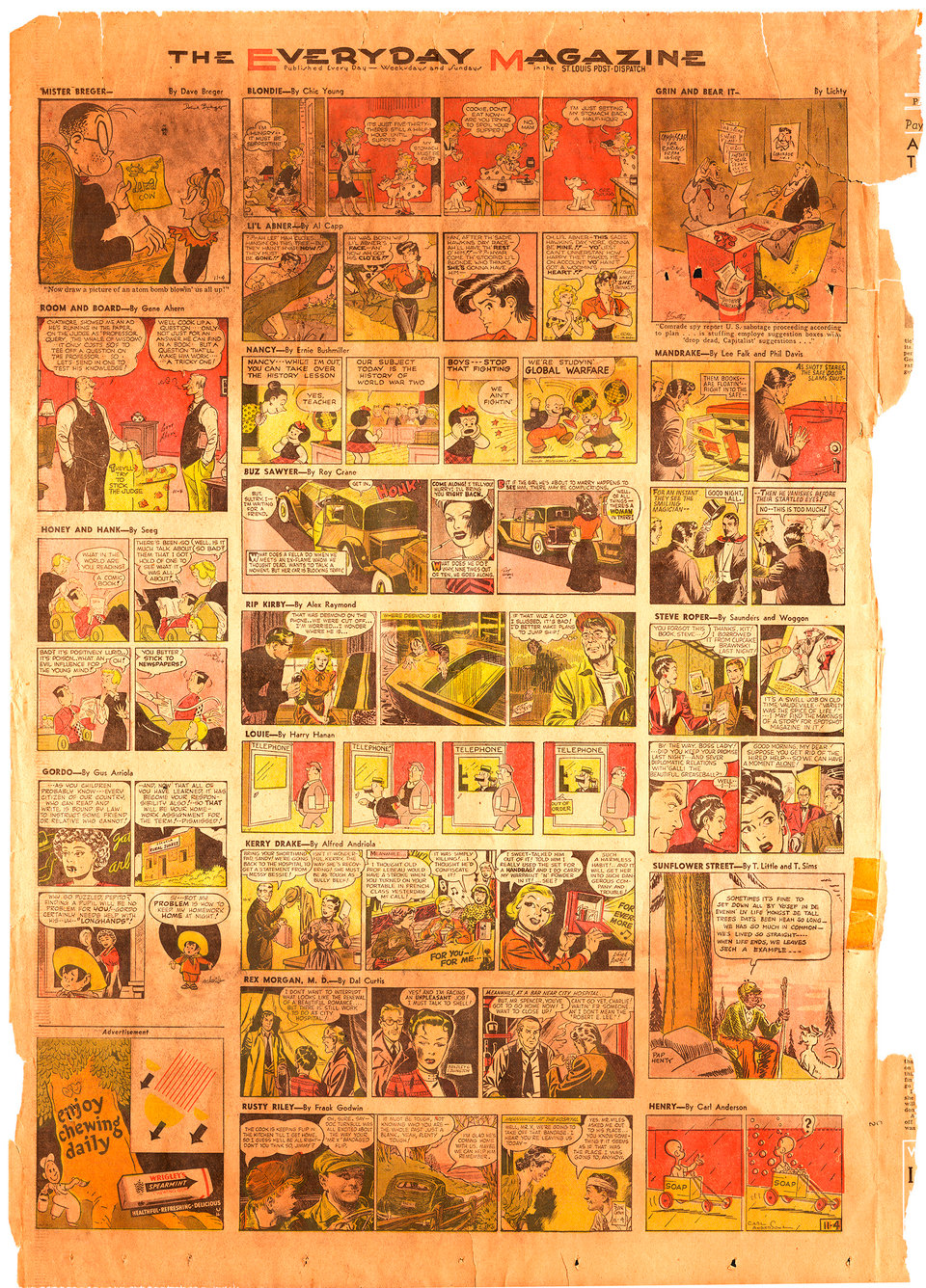

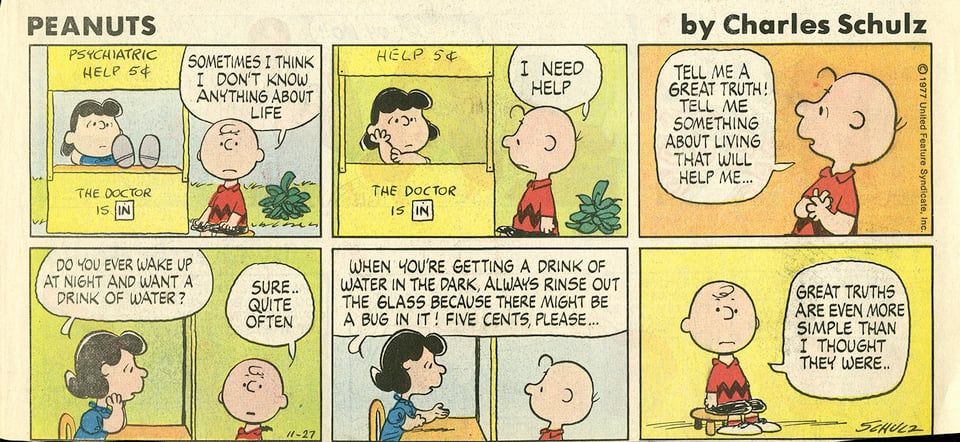

From both viewing historical color comics and reading trade journals, my suspicion is that every newspaper and every printer had its own ideas and formulations of color inks until standards were developed for routine, consistent reproduction. That was probably not until the 1950s, by my reckoning, but was certainly true in the 1960s.

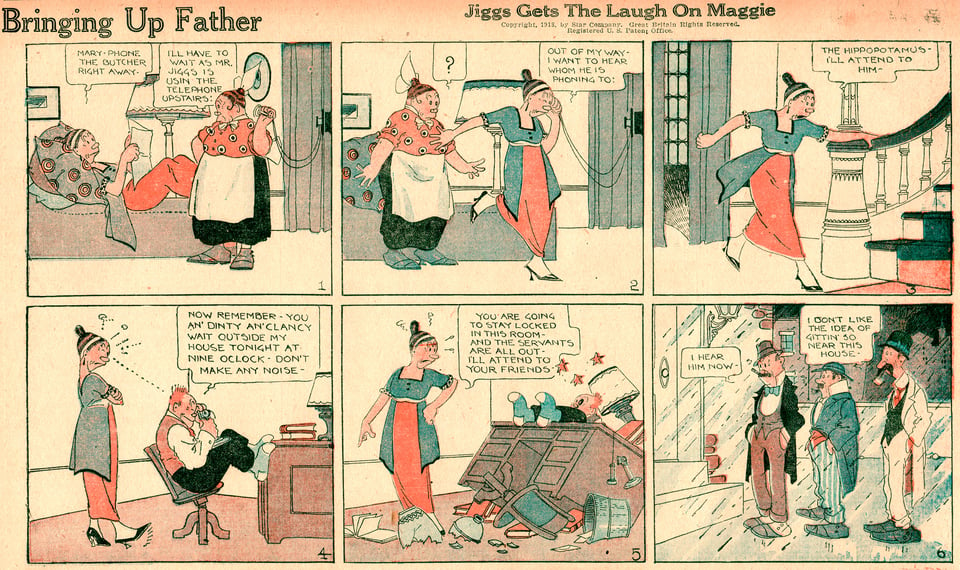

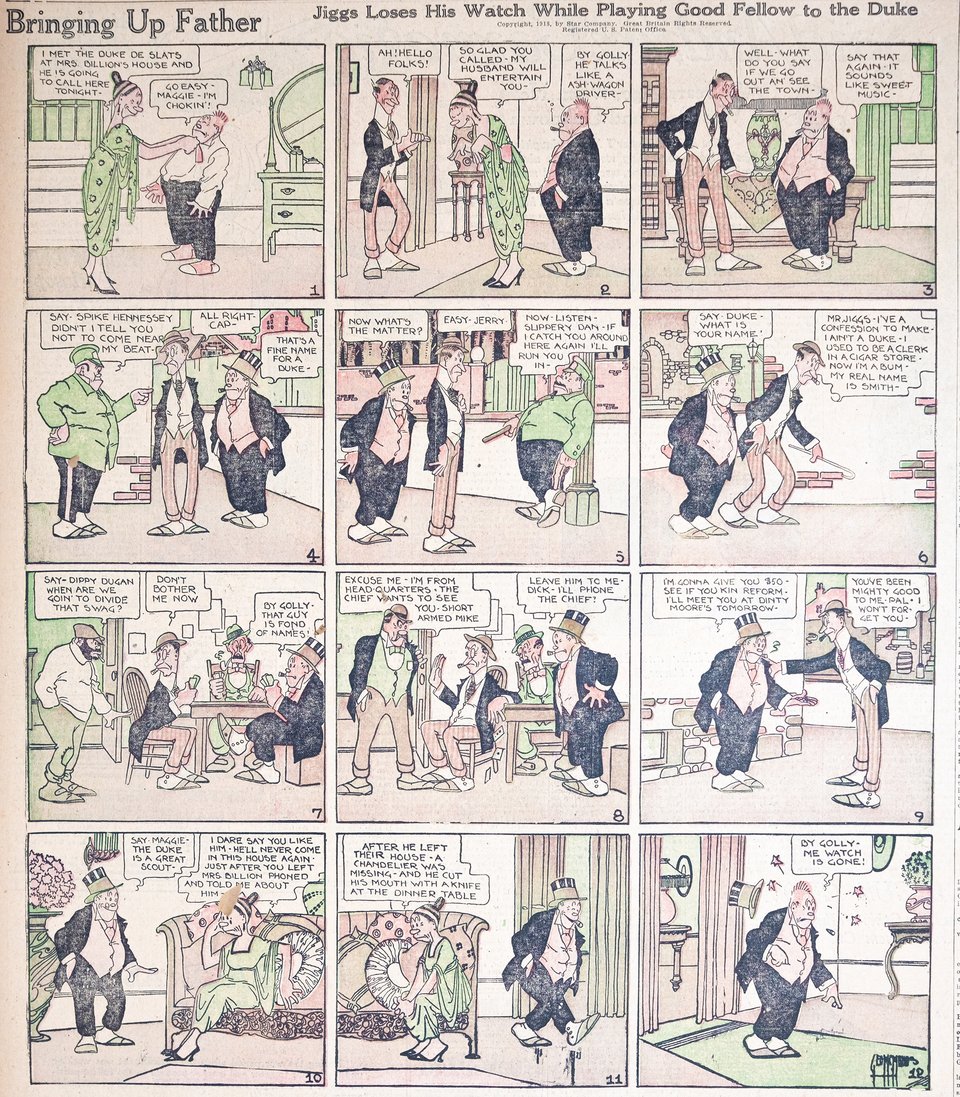

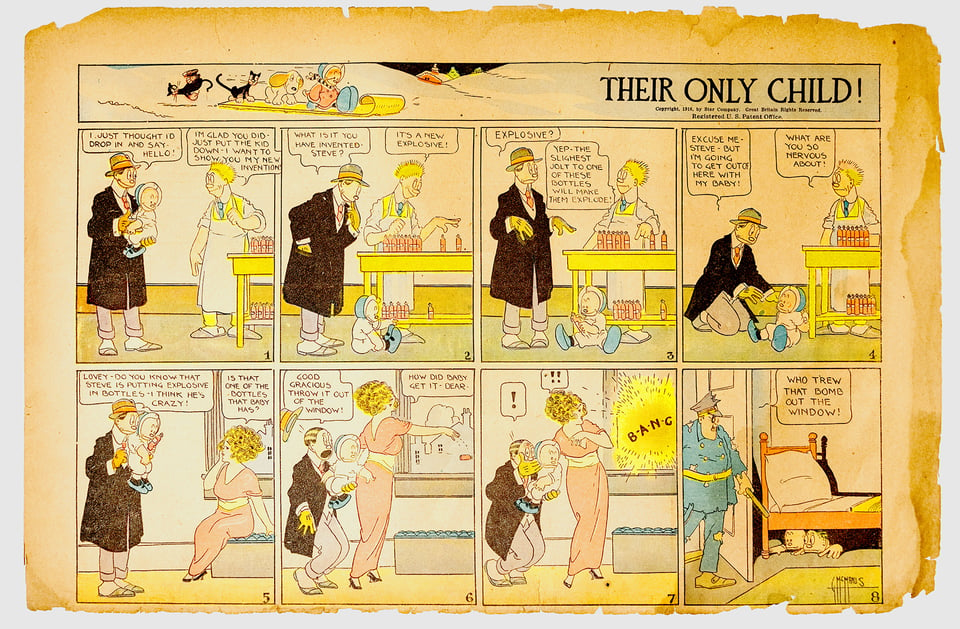

Throughout my book, and as you’ll see below, I track various iterations of one-, two-, three-, and four-color comic printing. These examples—though many are faded—can help you see how those colors were used.

episode of Gasoline Alley, by Frank King, appeared

with glorious four-color shading. One of the most beautiful renditions of this era. (Courtesy Peter Maresca

and Sunday Press)

Add a comment: