How Comics Were Sold (to Newspapers)

Hello from the next installment of newspaper comics history and lore! In this issue, I talk about the way in which cartoons were advertised to editors by syndicates, and include some original Calvin & Hobbes publicity materials obtained through a confluence of great people.

Some housekeeping first!

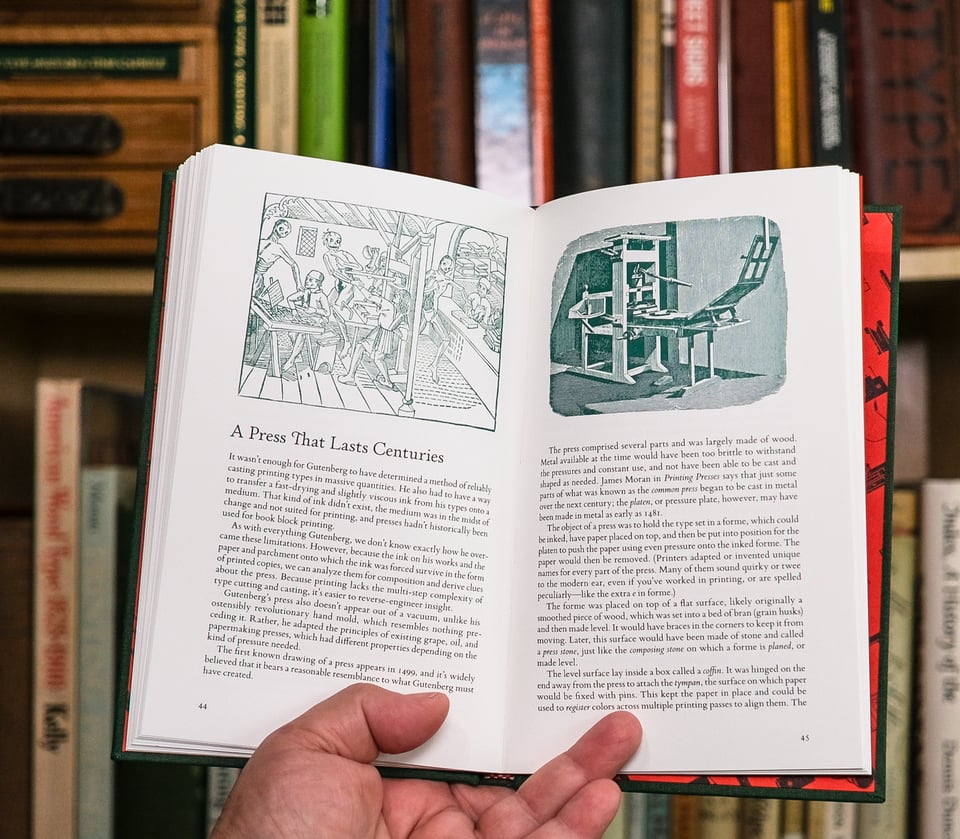

The new edition of my comics tome went on sale in bookstores on June 5! How Comics Are Made from Andrews McMeel is a hardcover edition with a few excellent new images on the dust jacket, plus a new printed case cover and fresh endpapers. You can find it in bookstores everywhere. If you’d like an inscribed or signed copy, you can order one directly from me. (Within the U.S. only.)

Related, the second edition of Six Centuries of Type & Printing shipped in July! This was a busy book year for me. This 64-page book, hardbound in cloth with foil stamping, covers technological developments across the titular six centuries—and even earlier! Regular, signed, and gift-wrapped copies available from my online store.

Billy Ireland Cartoon Library & Museum curator Caitlin McGurk won the prestigious Eisner Award for Best Comics-Related Book for her superb title (previously discussed in this newsletter), Tell Me a Story Where the Bad Girl Wins: The Life and Art of Barbara Shermund. Caitlin is a terrific researcher, writer, and curator, and was a great morale booster for my research into the space that led to How Comics Were Made, including connecting me to write a four-page “preview” of sorts in The Nib, which in turn led to me hiring Nib designer Mark Kaufman to design my book. Much-deserved award for her rediscovery of a lost, great artist.

Now onto this issue's main feature.

Syndicates Marketing New and Updated Comics

How Comics Are Made tracks the path of artists producing work that syndicates created finished versions of, which they then distributed on a continuous advance basis to newspapers. But how did newspapers become aware of new comics? From the very beginning of written and illustrated syndication, those sellers of mass-reproduced material had a sales force that provided advance samples to editors and forged relationships that could last from years to several decades.

At some point, syndicates started to create promotional packages with a very limited audience—just a few thousand people—who would make a decision typically to bump one comic or replace one that was ending with something new to the market. In the Nancy exhibition at the aforementioned Billy Ireland last year, a promotional item from the 1930s showed how United Features reintroduced to editors the strip Fritzi Ritz about a flapper to refocus on Fritzi’s niece, Nancy. (I sadly didn’t take a photo.)

Very few of these editor-oriented mailings appear online, and I can’t find a date for the earliest promotional material. The Billy Ireland Library holds archives that would help answer that question—such as this part of the Toni Mendez collection—and it would be a great topic for future research.

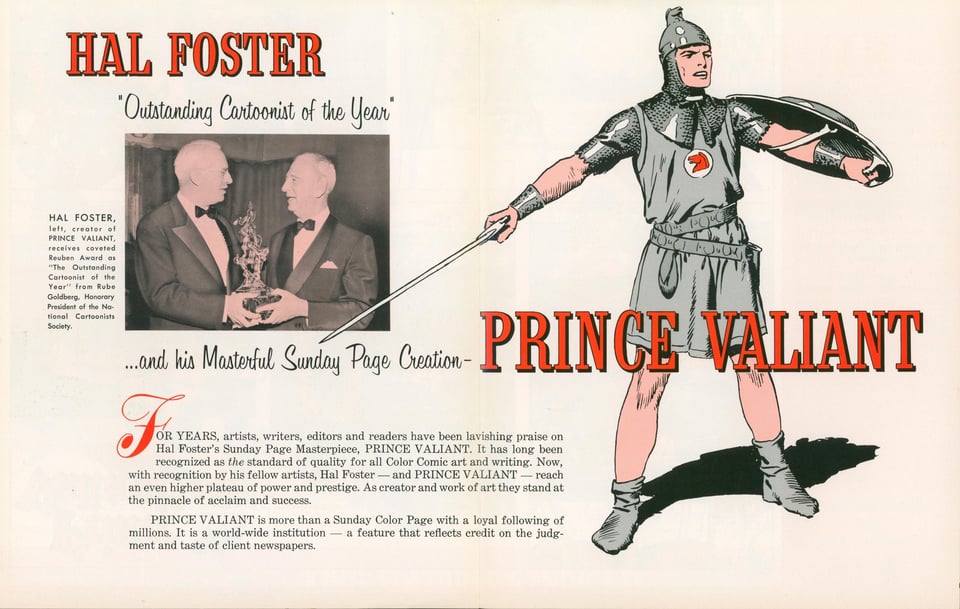

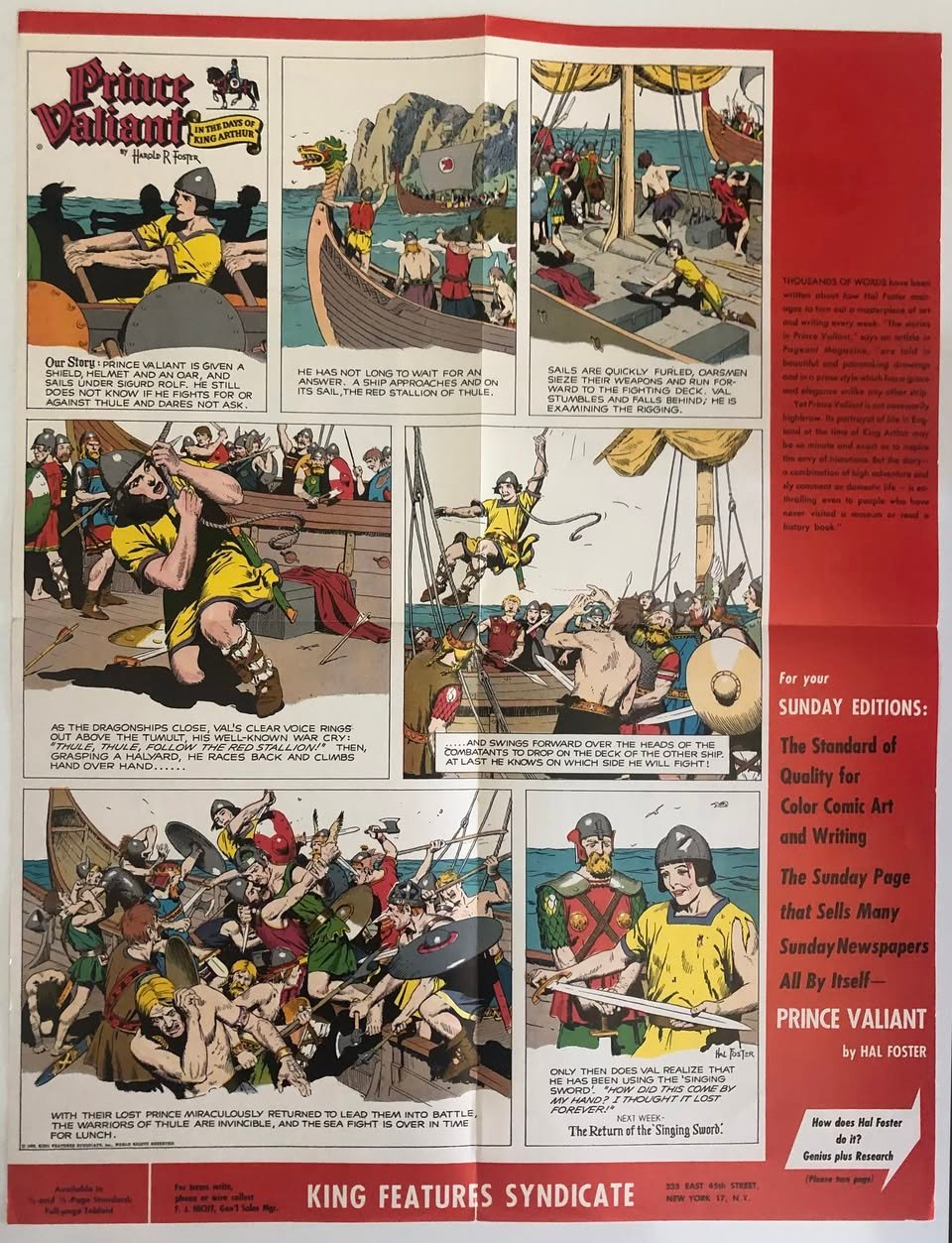

Thomas Ward posted images on Facebook from a 1958 promotional mailing by King Features hyping Hal Foster and Prince Valiant, surely one of the greatest comics ever drawn. The only baffling thing about this pamphlet is why King would even need to promote it—surely it was already running in one of the multiple competitive newspapers in most major cities, which would have a geographic exclusive on running it?

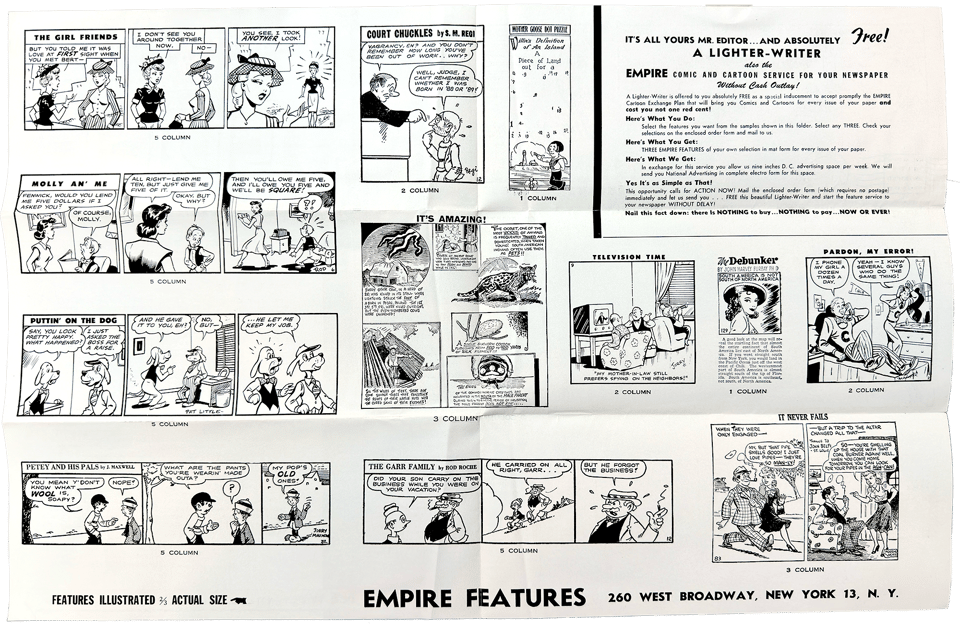

Empire Features (also know as Meyers List and International Cartoon Company) offered less-than-daily and inexpensively produced newspapers free comics in exchange for ad space, which they then sold as a block of circulation to national advertisers. They promoted themselves as having strips that would fit any format. (I devote a chapter to this syndicate in How Comics Are Made.)

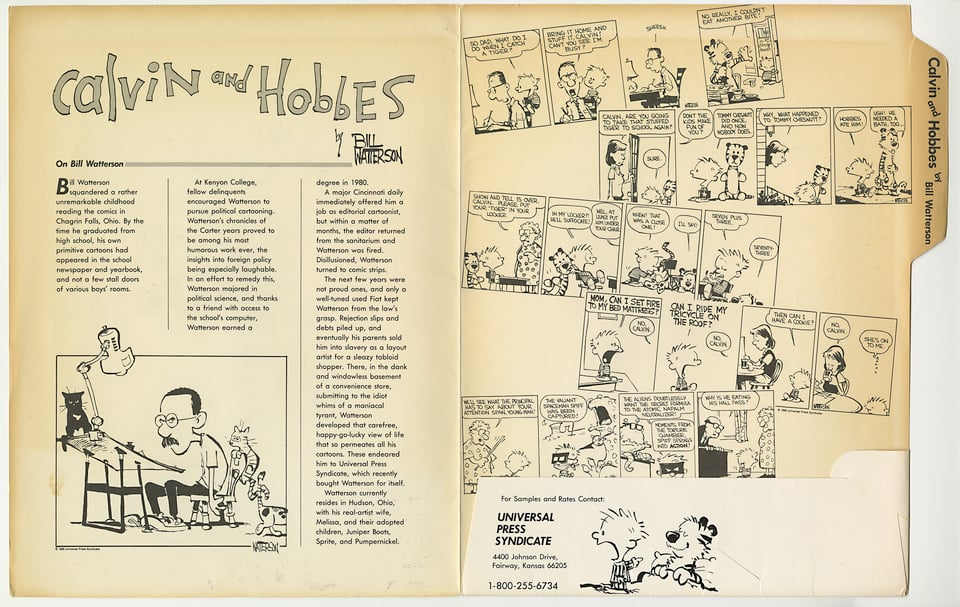

The most recent example I’ve seen of a promotional packet is a 1985 United Press Syndicate folder for Calvin & Hobbes. (UPS is now part of Andrews McMeel Universal.) It included background information, a reproduction of an article about Bill Watterson, and sample strips. Actor, podcaster, and professional George Lucas impressionist Connor Ratliff collected this example when he visited a newspaper editor who was friends with his parents. (Connor let get a scan of this; friend Nick Sherman did the digitizing. Thank you both!)

Even with the decline of American newspaper circulation, syndicates are still out there pounding the virtual pavement, as they work with papers or editors revamping comics pages—sometimes even adding more daily ones!—and negotiate rates and more. Syndicates also battle each other for space, offering package deals that must provide cost savings, as multiple newspaper chains have snapped up the deal, casting aside comics from other syndicates. (See this Daily Cartoonist article for a 2022 example.)

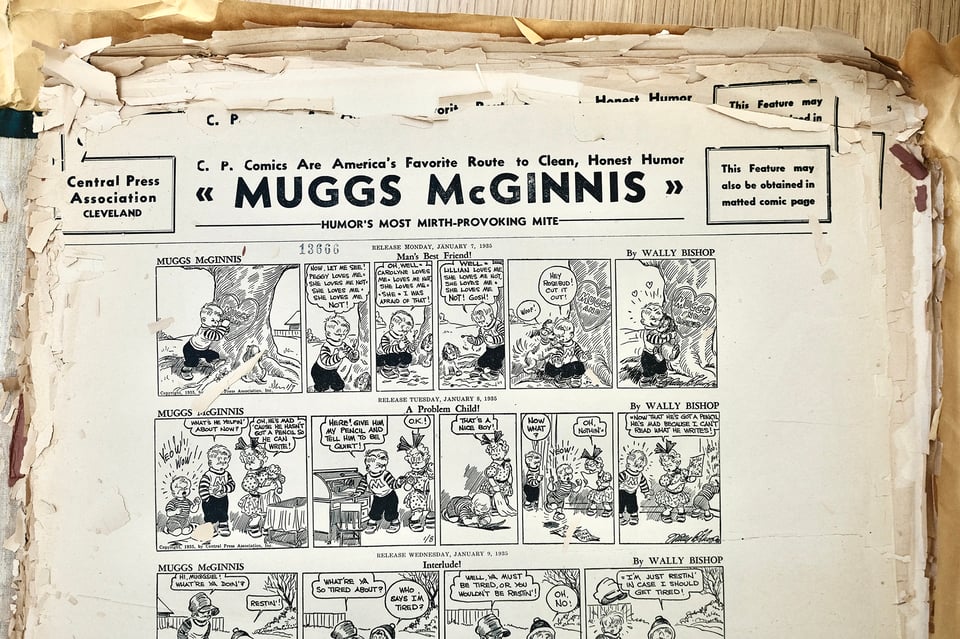

In a putative future edition of How Comics Are Made, I would likely add a chapter about distributing comics on paper, an aspect I breezed over, since it required much less explanation, but has wonderful graphical examples. (See page 181, which has a rare photo.) In the image below, a week of Muggs McGinnis from 1935, you can even see a note in the upper-right corner about that alternative: “This Feature may also be obtained in matted comic page.”

Deon Parson told me recently that his Rosebuds strip, distributed by King Features, is still sent out in this format—albeit now as a PDF. You can find it in that uncut original style at AOL, which, yes, still exists.

The marketing brochures in this newsletter, and others I would would hope to uncover, would also appear in that chapter due to the strong overlap between “previewing” comics to editors and distributing comics as short-run printed items for reproduction in newspapers.

Add a comment: