Draw, Partner

Hello, and welcome to a late-ish latest installment of the How Comics Were Made newsletter! My aim is to send something out roughly monthly, but it has been a busy fall!

The book that launched this newsletter is now out! You can purchase a print edition or ebook edition of How Comics Were Made for immediate shipment or download, as well as a print/ebook bundle. Some limited special rewards from the campaign remain available, too.

Now on to the newsletter. In this issue, I look into a long-running (and false) narrative about Garry Trudeau and his artistic abilities.

Who Draws Doonesbury?

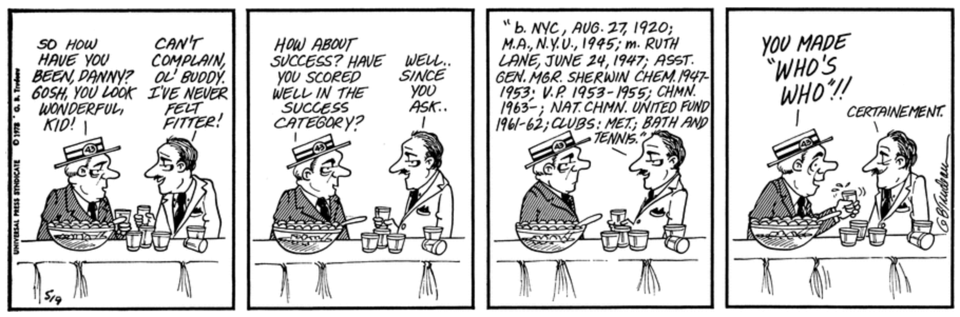

There’s a recurring myth in a corner of comicdom: that Garry Trudeau hasn’t drawn Doonesbury since before his very early years when the syndicate connected him with inker and colorist Don Carlton. I’ve heard other successful cartoonists repeat it despite the ample evidence to the contrary.

Trudeau works like many comic strip creators have across the span of the art form. From the very beginning of his comics career, he has plotted the story arcs and one-off strips or weeks, written the dialog, penciled the artwork and text, and then handed it off to someone else for inking, lettering, and coloring. (At one point, that was a single person: Carlton.) Trudeau oversees the whole process, as he has since he started distributing his workload in 1971.

What I suspect people derive their take on Doonesbury from is how dramatically Trudeau’s style improved between his college comic Bull Tales and early Doonesbury strips within a few years of syndication. His lines, character consistency, backgrounds, and lettering all get a lot better. That certainly results from artistic maturity, and you can see it in nearly all cartoonists’ work.

There are exceptions to this rule. That generally includes people who start out with such a professional style that they change relatively little over the run of their strip. This typically occurs with artists who have already, often quietly, spent years in the trenches working at a newspaper and producing massive amounts of illustrations, editorial cartoons, or even a single-newspaper or regional strip.

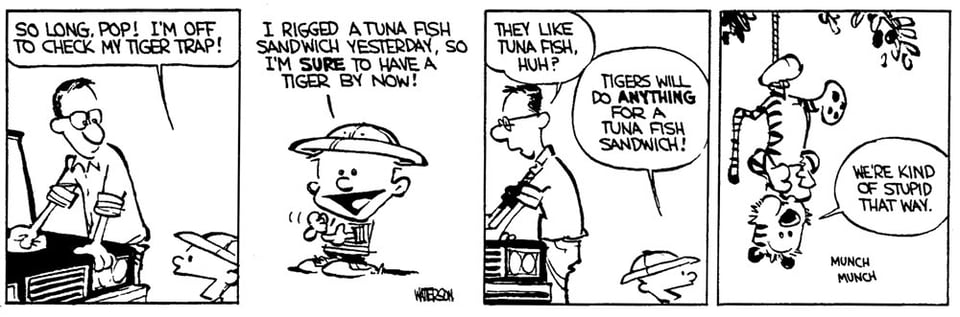

Bill Watterson is a great example. His Calvin and Hobbes appeared on day one in 1985 in mostly the form it remained through 1995—some characters’ appearances change slightly over time, but not substantially. His use of line and form improves but it starts so strong that it’s a study in subtlety. Watterson had spent years at The Cincinnati Post and submitted a number of comics to the syndicates that weren’t taken up before Calvin and Hobbes. We didn’t see his evolution in print. You can compare his 1979 college style with his 1985 syndicated first installment.

The same is true of the late Richard Thompson, the widely beloved creator of Cul de Sac. From 1985 to beyond entering syndication with the strip, Thompson was an in-house staff illustrator at the The Washington Post. Cul de Sac arose from his Post style, appeared there first in 2004, and entered syndication a couple of years later. Twenty years in the salt mines plus his talent and hard work gave him a style that was shockingly fully developed when he reached a broader consistent audience outside the Post. (Watterson and Thompson had a conversation for the book The Art of Richard Thompson, now priced as a collector’s item. Watterson said of Thompson’s strip at its introduction, “his drawings are wonderful—something one doesn’t often see in cartoons anymore.”)

Some of this maturity comes from having more time to develop one’s style. Trudeau wrote and noted in interviews the workload producing five strips a week took on him while an undergraduate in college was already intense. That changed to six dailies initially while he was attending graduate school, and then a Sunday added later. (He finished graduate school in 1973.)

In the last newsletter issue, I noted the key role that Brian Walker has played and continues to play in newspaper comics scholarship. He and a few other family members and close comrades produce Beetle Bailey and Hi & Lois, and Brian just curated the just-closed Nancy exhibition at the Billy Ireland Cartoon Library and Museum. (They recently lost Chance Browne, the son of Hagar the Horrible creator and Hi & Lois co-creator Dik Browne.)

Brian had known Trudeau since not long after the start of his professional career, in 1973, and curated an early exhibition of Trudeau’s work in 1983 at the Museum of Cartoon Art, the institution started by his father, Mort, with Brian’s keen involvement and curatorship. (The museum went through three names: from 1974 to 1992 as MCA, from 1992 to 1996 as the National Cartoon Museum, and from 1996 to 2002 as the International Museum of Cartoon Art. Its archives were donated to the Billy Ireland.)

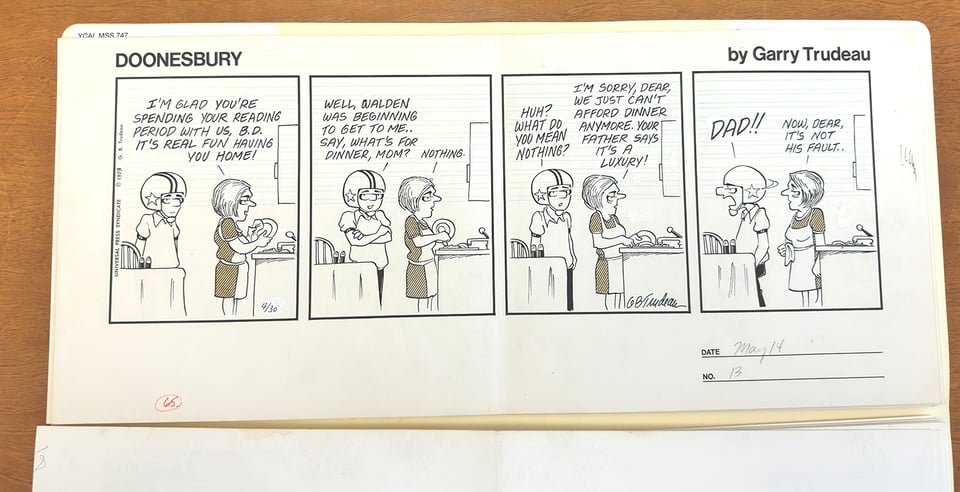

From 1971 onward, Trudeau drew a pencil version of the strip and then shipped it to Don Carlton, his inker through 2014 and colorist through 2001. Very few of the penciled drawings were ever seen. They would sometimes come up for auction for charities or when a gift recipient donated to an institution or sold a strip that Trudeau had penciled.

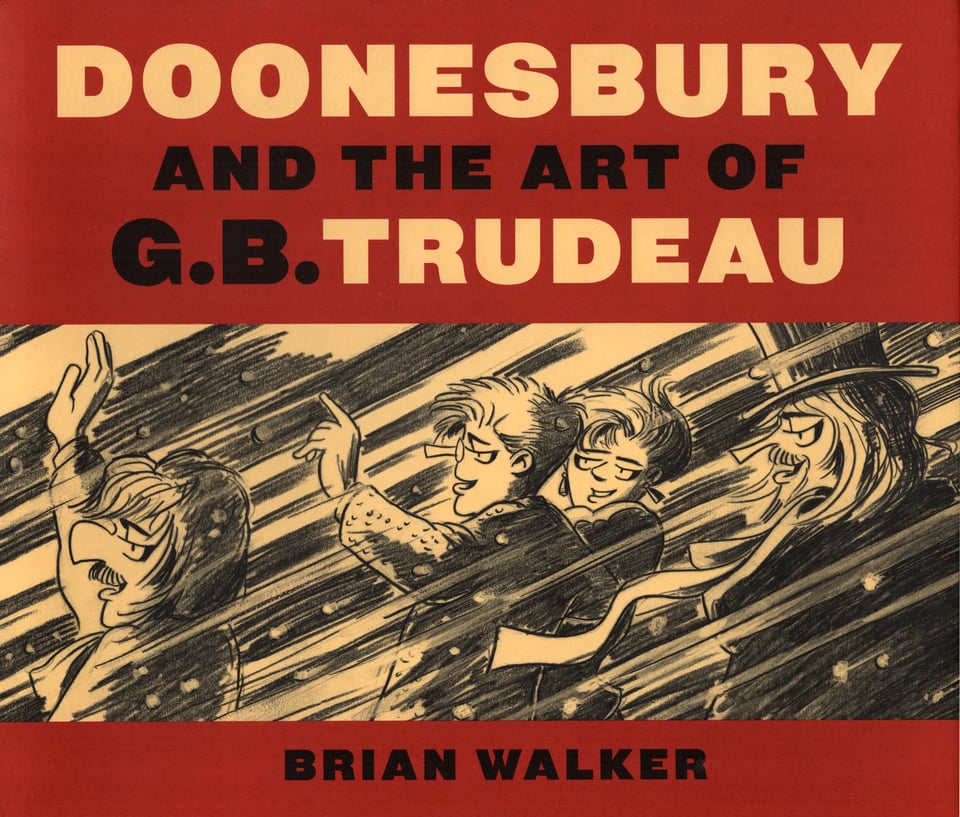

Brian had the great idea of showcasing the unseen part of Trudeau’s work in the 2010 Doonesbury and the Art of G.B. Trudeau. As a 40-plus-year fan of the strip, it was the first time I was exposed to Trudeau’s original artwork when I read it last fall. Brian wrote in the introduction, “I had always felt that he had not received adequate recognition for his talents as an artist and graphic designer.” Clearly, not until this book!

As my friend Dan Perkins (his nom-de-plume at This Modern World is Tom Tomorrow) wrote in a review in 2010 of Brian’s book:

Anyone still laboring under the misimpression that Trudeau is anything but an accomplished and talented artist should be thoroughly disabused of the notion by this volume, rich as it is with early sketches, pencil drawings, paintings, and other artistic output spanning his long career.

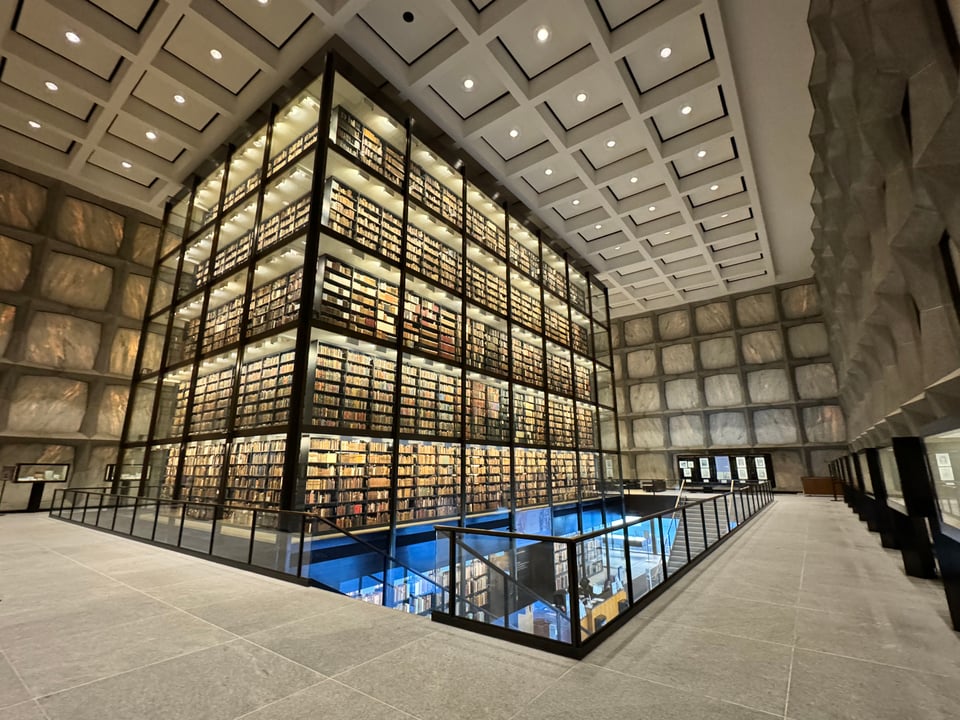

In researching How Comics Were Made, I was able to get a firsthand look at Trudeau’s 1970s notebooks. The cartoonist has donated his work in tranches to the Yale University Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library. As a Yale undergrad, I had spent many happy hours inside this gorgeous edifice to preserving books and archives. (Trudeau’s originals, printing artifacts, and printed newspapers versions features in the chapter “The Week in Doonesbury That Wasn’t,” covering John Ehrlichman’s resignation from the Nixon White House, which in turn required a week of Doonesbury to be pulled from newspapers.)

A librarian was able to send me a digitized version of a couple of the journals covering the period of my focus in the book during Watergate. These were a pleasure to review, and I later held them and paged through them in April during a rapid research trip to three colleges’ collections. Fortunately, the Beinecke had just finished cataloging Trudeau’s original daily artwork—but not yet the Sundays for that period—when I visited, and I was able to look through hundreds of pieces of penciled, corrected, and inked artwork from the early 1970s, primarily focused on 1973.

Trudeau was exceptionally helpful with my book, providing answers to questions on the above chapter and permission (along with his syndicate, Andrews McMeel, which incorporates Universal Press Syndicate) to reproduce the work. Some of this didn’t make it into the book because it was about the artistic workflow than print production.

Trudeau said he used to pencil six weeks of strips at a time and use USPS Special Delivery to send those to Carlton, always cutting it close for Don to have time to ink and Trudeau review strips before the syndicate’s deadlines. He said he switched to FedEx when it was invented, and by the 1980s used a fax machine. (Trudeau, like Watterson, may have kept FedEx in business on the weeks they ran so late that Universal Press had to send thousands of packages out to newspapers to meet print deadlines.)

I asked if he had some special technique for faxing, and Trudeau replied that Don Carlton “was so used to my line that he could put them on a light box and trace in ink without difficulty.” Later still, Trudeau sent digital versions.

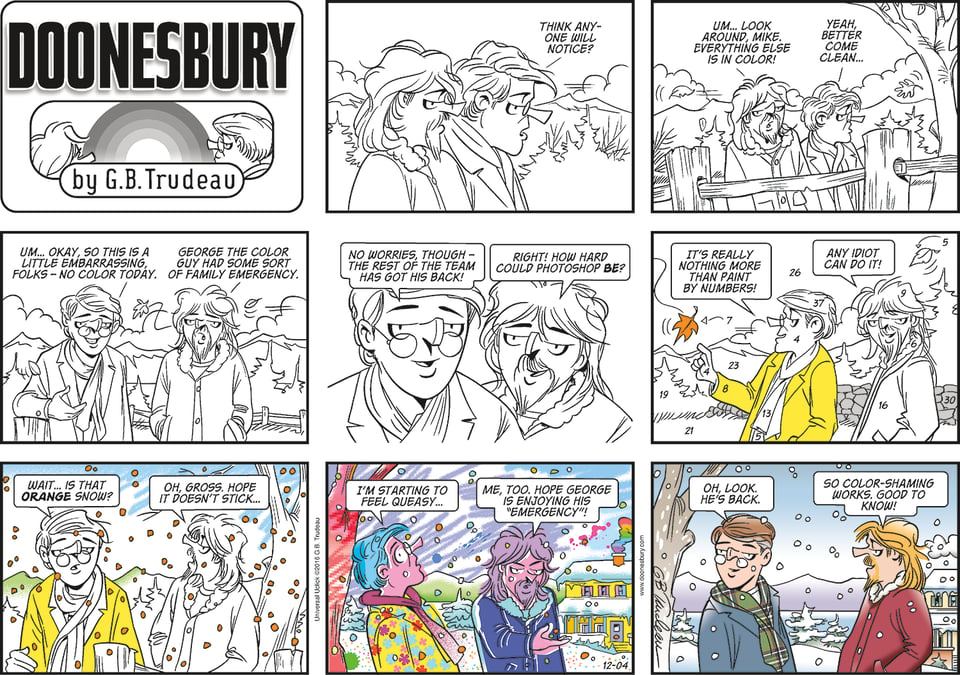

Dan Carlton stepped back from the colorist job—marking up color on a black-ink version of the comic—and George Corsillo took over that task in 2001. Carlton retired in 2014 at the same time that Trudeau moved to produce only new Sunday strips. Todd Pound took over inking. Carlton passed away in 2023.

During my research, I got in touch with George Corsillo and eventually made plans to meet at his studio on my April trip, squeezed between research at the Beinecke and a studio visit to Bill Griffith, the creator of Zippy the Pinhead. George and his wife, Susan McCaslin, run a studio called Design Monsters in New Haven, Connecticut, a few miles from the Yale campus. (Bill lives in a surprisingly rural part of Connecticut, given his urban and urbane nature.)

George and Susan are lovely people, and I could have spent days with them. Their studio work is marvelous, and if you search for George online, you will find that he designed many of your favorite 1980s and 1990s book covers and album covers. He also designed Brian’s Doonesbury and the Art of G.B. Trudeau! George designed the cover of one of the Doonesbury collections in the mid-1980s for Trudeau’s publisher; Trudeau loved it and has worked with Corsillo on every design project since, Doonesbury or otherwise, starting before George became his colorist.

George was very gracious and showed me the process of receiving inking and instructions, closing up open areas when using color fills, creating and adding gradations, and testing out ideas that Trudeau often signs off on with no changes required. George told me, “I have open reign to do stuff, but he always sees [it] before it goes out.” Trudeau tweaked George in one Sunday comic that, of course, George had to color! I was able to reproduce this in the book to show off George’s work alongside Trudeau’s.

There’s a group called Team Doonesbury that comprises Trudeau, Pound, Corsillo, and David Stanford, a long-time jack-of-all editorial and project trades. George says they all get together in person about once a year. Trudeau mentioned them in passing in this 2015 blog post celebrating 45 years of Doonesbury. The 50th happened in the depths of the first year of the pandemic.

I grew up reading Doonesbury in the newspaper and devouring collections of the old stuff. It was part of my education in political history, domestic and international, and part of why I never liked Henry Kissinger. Trudeau was ahead of his time in the widespread disdain for the man.

Getting to tell the story of an early bit of Doonesbury history was one of the delights of writing this book; having Garry Trudeau interested enough to participate, the cherry on top.

Add a comment: