Chalk Talk: How a Cheap Plate Persisted for Illustrations in an Etching Era

Greetings, comics history lover! In this newsletter, I jump us way back into the 1800s. First, a quick update on How Comics Were Made.

Book Heads to Printer in Mere Days

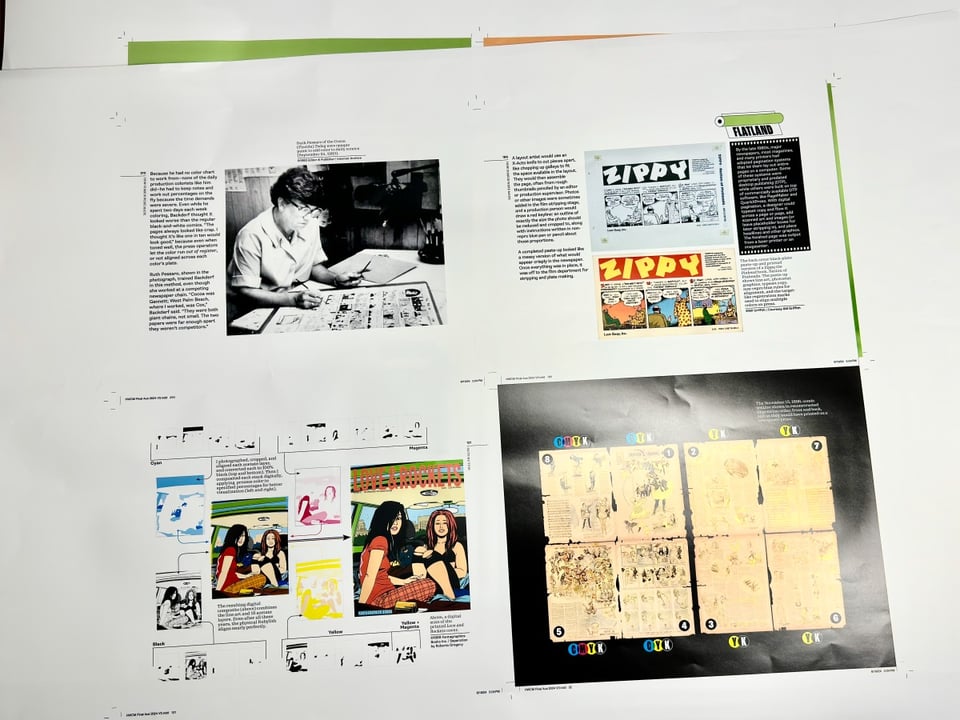

It’s possible you noticed a longer delay than usual since the last installment of this newsletter—I’m aiming for monthly. That’s because I’ve been working nonstop on How Comics Were Made. The book is effectively finished. I’m entering some last-minute corrections and feedback, waiting on the index and foreword (both coming very shortly), and examining test color proofs I just got back to make sure my color correction and light/dark balance (dynamic range) are correct from digital to print.

The book features insights via email from Bill Watterson about how he approached coloring Calvin and Hobbes and Garry Trudeau on a week of Doonesbury strips that never ran in 1973 during Watergate, production materials and original art from Lynn Johnston (For Better or For Worse) plus comments from an interview with her on printing in color, and a huge array of Peanuts materials made possible through the kind permission of the folks at the Charles M. Schulz Museum, Charles M. Schulz Creative Associates, and Peanuts Worldwide LLC. Dozens of interviews have been distilled and hundreds of pieces of art prepared. There’s so much else I’m bursting to share—so many items have never been seen before in print or online.

In about two weeks, I will upload gigabytes of files to my Canadian printer, Hemlock, and then they set to work on digital prepress, sending us proofs and setting up to print. In late September or early October, I’ll travel to the Vancouver suburb they’re in to oversee the printing. Then, around mid-October, the first books will be packed up and sent off!

Excitingly—for me, at least—the printer uses an HP Indigo for proofing. The Indigo is a laser printer that uses liquid inks that allow close calibration with their press and almost any substrate, such as the paper the book will actually be printed on. They printed loose sheets for me for this test, but the full set of color proofs for my book will be printed and bound—the proof will look almost identical to the final book. This is a game changer across my 40 years in print production.

One final bit of news: I had to set a total number of books to print—the print run—with Hemlock, so now I’m starting to count down the number of copies remaining. About 70% of copies are now sold from that total. You (or anyone) can still order the book!

And, now, some comics printing history.

Chalk Plates for Quick Cartooning and Illustrations

The joy of researching is coming across absolutely baffling information or artifacts. That happened to me in April 2023 at the Billy Ireland Cartoon Library and Museum (BICLM), part of the Ohio State University in Columbus, when I started going through a box of material that was part of the International Museum of Cartoon Art (IMCA). (IMCA at BICLM is a lot shorter than those full names! See the next section for more on IMCA.)

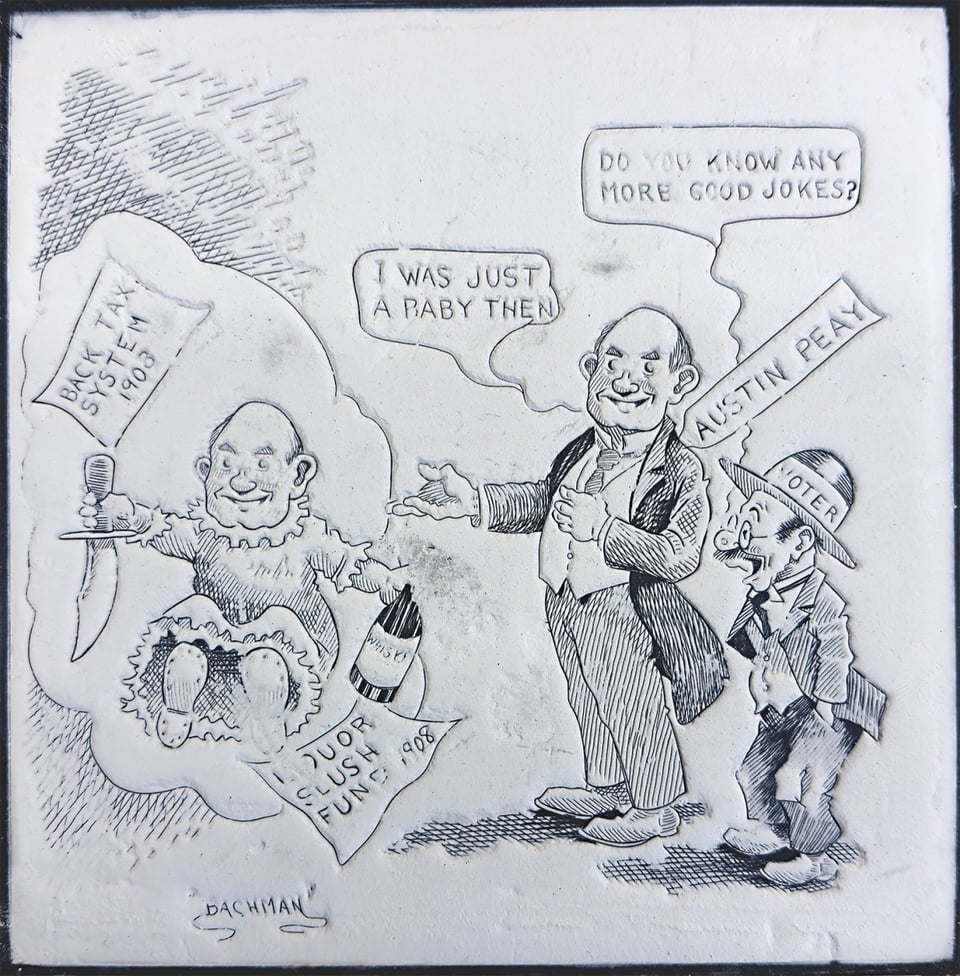

The box I had requested mentioned a printing plate in its catalog listing. As I went through the contents, I unpacked an item that felt heavy for its size from the newspaper in which it was wrapped. The best I could tell was it was an editorial cartoon that had been scribed with a pen into a layer of chalk above a plate. Unusually, it was right-reading, which made it likely to be a mold from which a mirrored (wrong-reading) metal plate or other intermediary stage would be cast.

I asked the librarian, Susan Liberator, who knows where everything is—and she had never seen it or anything like it. So I dropped a line on the spot to Brian Walker. Brian is part of the team that produces Beetle Bailey, a strip created by his father, Mort Walker, and Hi & Lois, a team effort with co-creator Dik Browne’s family. (In the Beetleverse, Beetle and Lois are cousins.) Dik also created Hagar the Horrible.A group of folks come up with gags, pitch them to each other, and then the artists among them draw the strip. For Beetle, that’s Greg Walker, Brian’s brother. (I got to meet Brian at Nancy Fest, a two-day event centered on an exhibition of Nancy comics and cultural influence that he curated.)

Brian replied immediately to my email about the chalk plate: he didn’t remember the plate at all, but he did point me to some historical research, and I took it from there. A tiny fraction of what I learned about chalk plates will be in my book, so I’m delighted to share a larger chunk here.

Where this chalk plate starts from is a problem that newspapers had in the mid-1800s: as presses became capable of producing more volume—more pages in an edition and more copies—newspapers wanted to add more graphical material. Literacy in most countries remained modest compared to today, and pictures sold papers. Extremely popular magazines featured extensive illustrations, including Harper’s Weekly(from 1857) in the United States, and The Illustrated London News (from 1842) and The Graphic (from 1872) in England. These publications sometimes licensed drawings to one another. One appearing in my book was created to celebrate 400 years since William Caxton brought printing to England. It first appeared in The Graphic, and then not long after in Harper’s Weekly.

These illustrations relied on a wood-engraving technique developed in the late 1700s by Thomas Bewick using the tight, hard endgrain of wood. The improvement in making molds from printable material, like typeset copy, eventually worked well enough with wood engravings to allow them to be part of newspapers printed by high-speed rotary presses.

Wood engraving was slow, however, even though the artists and engravers had worked out a system in which an artist would draw the original on a series of locked-together blocks that could be separated for simultaneous engraving by several different craftspeople.

Modern photography was invented in 1841, but it wasn’t ready to be part of standard printing used in newspapers until the 1880s. (The first halftone photograph appeared in print in 1869, but it was an outlier.)

Filling that gap? As unlikely as it sounds: chalk! Chalk plates allowed an artist to sketch a drawing and then cut it into the chalk down to a metal substrate beneath the chalk layer.

The “chalk” was a mixture of engineered precipitated chalk (calcium carbonate), barium sulphate, and china clay (kaolinite) to which a little silicate of soda and water were added. It was baked onto a steel plate and then scraped to a level surface.

Practical Art: A Complete Course in Drawing, Commercial Art, Newspaper Art, Cartooning, Fashions and Illustrating by Manuel Rosenberg, a 1924 book about becoming a working artist, explained that the thickness was about “three sheets of manila tagboard,” a measure that I can’t find the equivalent of. The IMCA plate had a chalk layer of roughly 0.25 inches (65 mm). A later recipe, from a 1941 issue of Popular Mechanics, suggested using plaster of paris (powdered calcium sulphate), a readily available substance since antiquity, which I would have thought would be too brittle.

After creating a sketch in pencil, ink, or other medium on the dried chalk surface, an artist used a “graver,” a stylus with a pointed end, to dig into the chalk. They had to be sure to reach the metal surface as that would become the top of the cast plate. When the graving was complete, a printer would set it up level in a frame and pour lead in to create a printing plate. When the plate was removed, the chalk material could be broken down and reused for future drawings.

My initial look at chalk plates made me think they were a stop-gap technology that had largely disappeared by the onset of the 20th century. In 1934, the early, mostly forgotten, and once-famous cartoonist Jimmy Swinnerton (Mr. Jack, Little Jimmy) told Editor & Publisher magazine:

Some 40 years back, we artists of the newspapers were a sadly driven lot. The ‘zincograph’ cuts had just replaced the old chalk plate, and in the change there was a rush to do great stuff with the new process which gave more latitude and speed in reproduction of pen and ink drawings.

Yet, with further research, who do I come across but Brian Walker’s dad, Mort, talking to the legendary comics journalist R.C. Harvey at The Comics Journal in a 2009 interview about chalk plates! Mort Walker clearly remembered using chalk when he was young—he started illustrating and drawing comics early, selling his first at age 11. Born in 1923, his memory of chalk plates dates from what he said were the late 1930s, using them at his high-school paper.

He described it this way:

There was a little device with a little point on it, and you’d use it to carve into the chalk coating, making your drawing. Then they would pour the metal over it, and come out with a pretty plate.…You’d cut down into the chalk, and there was a black backing under the chalk, so you’d see what you were getting.

The reason for the long life of chalk-plate engraving certainly stems from the cost of its replacement. Zinc plate etching, described at length in my book, required a whole operation. A newspaper or production shop would need the chemicals and glass plates to create their own emulsions for shooting negatives (negatives were not yet available as a stable film format), a large-format camera to capture oversized art and reduce it, metal routing and cutting equipment, zinc etching baths, and trained engravers, photographers, and other production experts. It was not a modest operation, with lots of people, equipment, and consumables. As the author Rosenberg wrote in Practical Art, “there is seldom an engraving plant in a town of less than 5,000 people.”

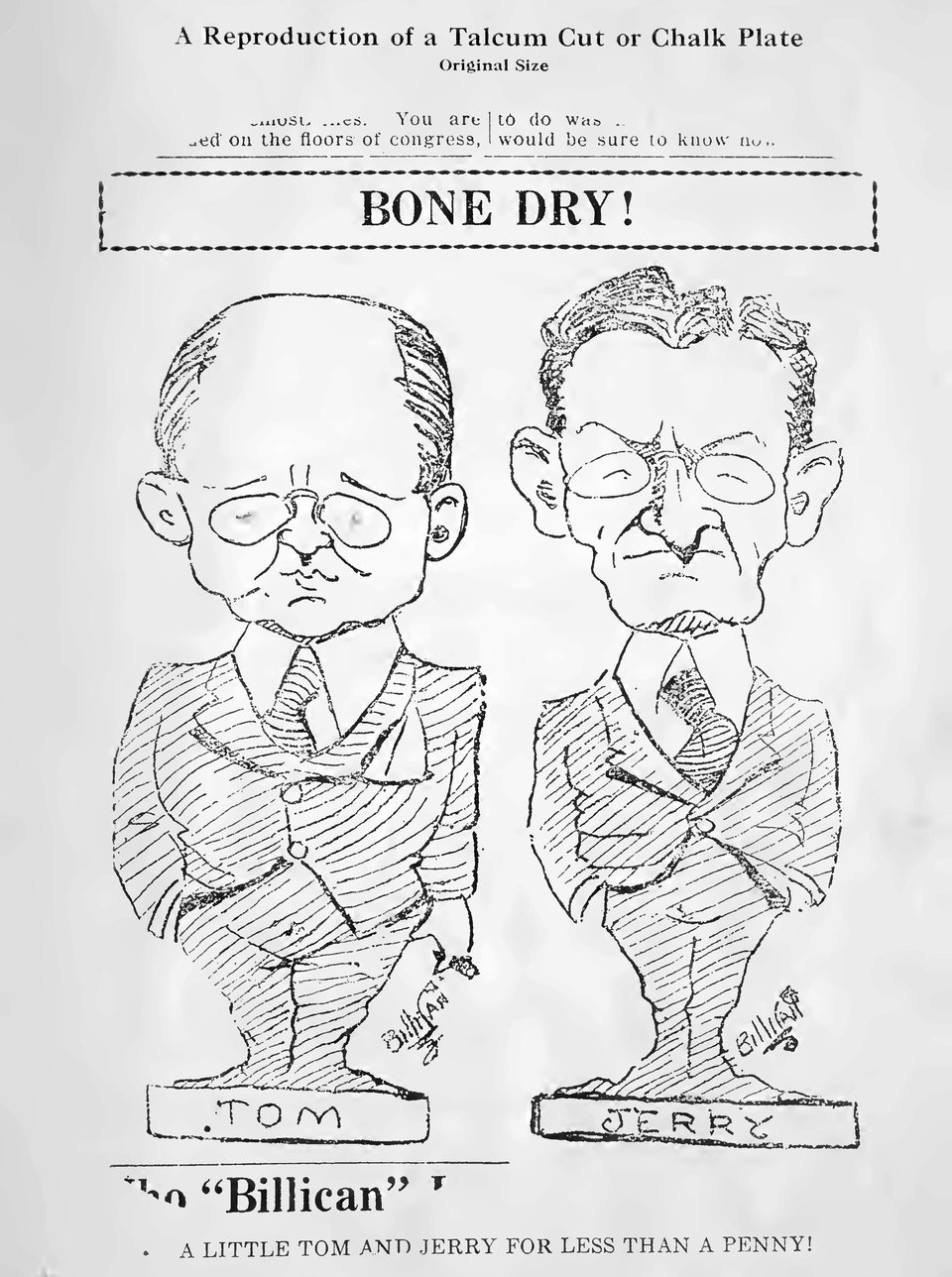

A chalk plate was simple to make and cast—no caustic chemicals, photographic processes, or even much expertise required. Printers routinely cast small amounts of material from molds up to entire printing plates using lead alloy. Casting a plate from a chalk source would be little different. They were also used to casting thin plates that were raised to the correct height as type and other material to print on a level surface.

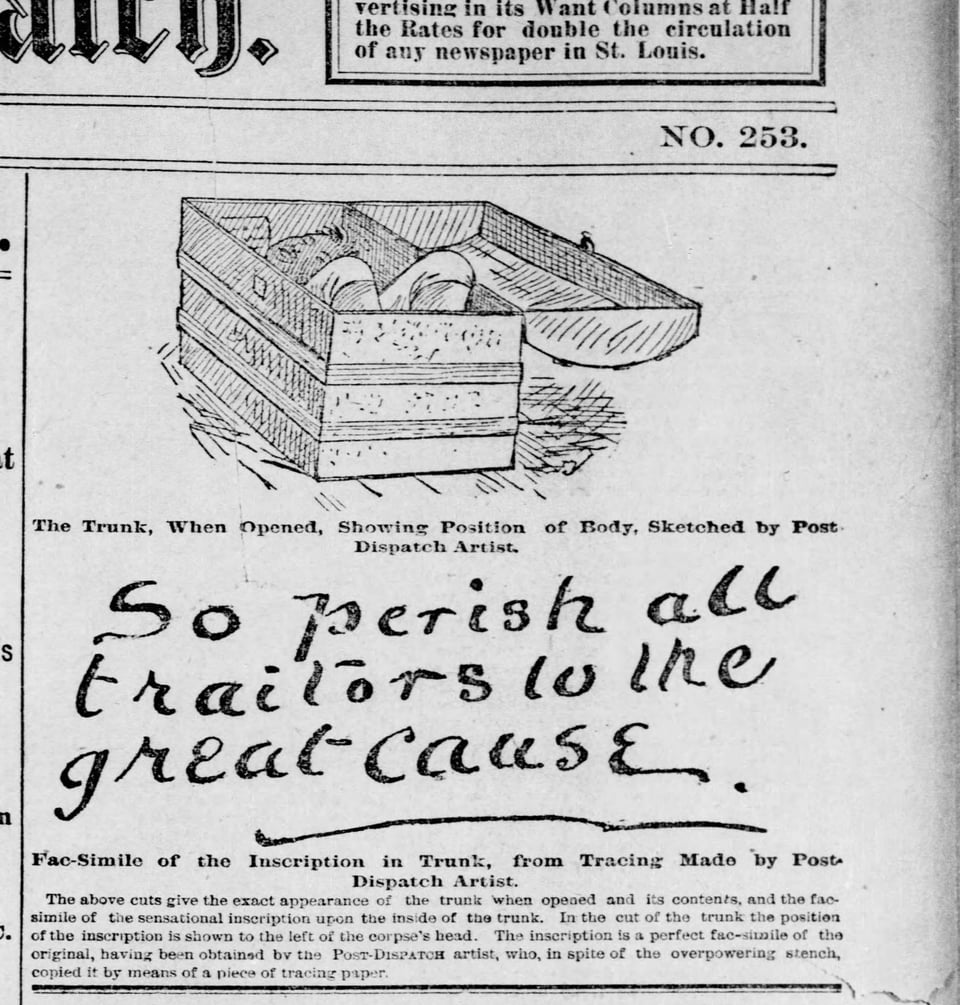

The earliest use of a chalk plate appears to be on April 15, 1885, when Martha Hoke, the artist daughter of inventor Joseph W. Hoke, sketched and created a plate for the St. Louis Post-Dispatch of a murder victim found in a trunk. She started around 1 pm, and the resulting plate appeared in an edition of the paper a few hours later. Hoke developed a production version of his process that he sold to newspapers for decades.

The persistence of chalk plates was surely due to their cost and rapid turnaround. The book Practical Art explained to an aspiring artist how to make and cast their own chalk plate, noting, “Often the chalk plate, on account of its cheapness, has been the means of an aspiring cartoonist in a small town actually getting his first work into print. For most hometown papers are always glad to print a picture by local talent, and are willing to go to the slight expense of a chalk plate to publish it.” But author Rosenberg adds, “Even in the large cities some newspaper artists use the chalk plate for making their ‘rush one col.’ comics,” or drawings one-column wide that needed to be made in a jiffy.

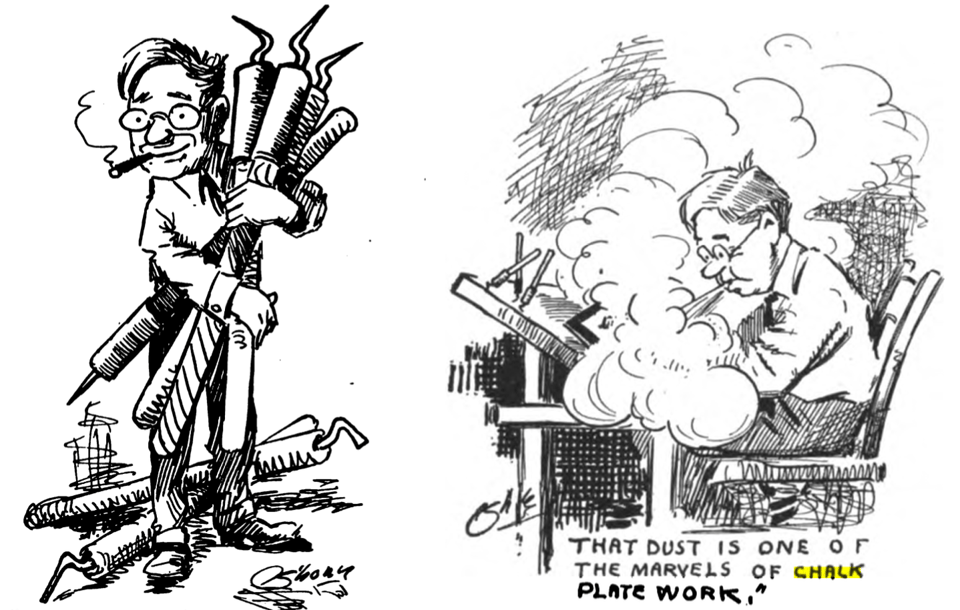

They weren’t easy to work with. In 1913, the cartoonist James H. “Shonk” Shonkwiler, a reporter and cartoonist for the Portsmouth Daily Times, wrote in Cartoons magazine:

In my humble opinion, there never was such a thing as an expert in chalk. When you think you have about arrived at the point where you know all there is to know about a chalk plate something happens to your work that never happened to it before—something that you had never dreamed could happen to it—and you find yourself beached once more upon the shoals of ignorance. The chalk plate simply defies expertness.

He described working with chalk in colorful terms:

Sounds perfectly simple—and it is. All you have to do is to be sure that the chalk is thick enough and all the lines in the right place. Nothing could be easier unless it is filling your lungs from the cloud of dust that rises like mists from the ocean when you blow away the loose composition in an effort to see what you are doing.

The last mention of chalk plates in use that I can find is that 1941 Popular Science article. In addition to Mort Walker’s reminiscence, however, Van Truan, son of cartoonist Jolan Truan, wrote to Allan Holtz at Stripper’s Guide to tell him about his father Jolan’s chalk plates: “My dad loved doing chalk plates and was considered one of the best in the country. The owner of the Pueblo paper was a tight wad, so chalk plates probably didn’t go out until the late 40s.” (I was unable to reach Truan to get more information.)

It turns out I’m not the only person interested in chalk plates. Dan Martin, the long-time cartoonist behind the St. Louis Post-Dispatch’s Weatherbird comic, was well versed when I interviewed him for my book. (Dan has been drawing Weatherbird since 1986, the sixth in a series of artists dating back to the creator, Harry B. Martin in 1901.)

The only surviving plate I’ve seen in person or in photos is the one at the Billy Ireland.

One of the Pillars of the Current Best Cartoon Museum

A short aside: Brian Walker was deeply involved in the creation of IMCA with his father and, from the 1970s onward, has become one of the most informed and best-regarded historians of the comic-strip art form. I own nearly all of his books. They’re good reads, full of hard-won and well-researched information, and also set a standard for the quality of reproduction of original and printed comic strips in books—I’m striving with my upcoming book to hit that mark.

IMCA was founded in 1974 in Connecticut in a disused mansion as the Museum of Cartoon Art. Mort Walker had seen the terrible way that original artwork was handled by syndicates and artists alike through the 1970s. In an account from The Wall Street Journal in 2008, “[Mort] would regularly walk into the New York offices of King Features Syndicate…and see crumpled up ‘Krazy Kat’ cartoons on the ground. They were used to absorb water from ceiling leaks, he says. ‘It just wasn’t right,’ Mr. Walker says. He began taking the drawings home.”

It changed names and locales a few times due to the facilities costs and other factors, ending up in Boca Raton, Florida, in 1992 as the National Cartoon Museum and becoming IMCA in 1996. The museum received significant funding from the Hearst Foundation, Charles Schulz, and other cartoonists, but ultimately was unable to attract a self-supporting volume of visitors, while some major donors reportedly had trouble meeting their commitments.

It shut down in 2002, and the organization donated its collection to BICLM in 2008. That donation, coupled with the hard collecting work already done at the OSU and the Billy’s 1997 acquisition of the Bill Blackbeard collection, the San Francisco Academy of Comic Art (SFACA), make it the research and museum powerhouse in comics that it is today.

Add a comment: