Black Faces in White Comics

In this issue:

An update on the book and research

A look at the modern depiction of Black faces in comics

A Quick But Significant Trip East

Some important papers and people remained for me to see for How Comics Were Made, and I took a quick trip to the tri-state (NJ/NY/CT) area last week to visit three universities (four libraries within them), two cartoonists, and a curator, with a bonus surprise chat with an psychiatrist who helped spur the effort to restore Winsor McCay’s early animated film, Gertie.

For those interested, you can read a fuller account with some photos in a Kickstarter update for the book.

And if you’d like to pre-order How Comics Were Made or have access to any of the higher-tier rewards, a mix of unique and limited offerings, those are all available via my PledgeManager pre-order site. For instance, you can still get rare “Peanuts” Sunday four-color flongs (printing molds) and a unique, limited-edition letterpress print/flong re-creation of a “Zippy the Pinhead” 1991 comic.

The book starts shipping in October 2024, and I’ll have some news in the near future about some fancy bits I’m adding to the print edition.

People of Color in Black and White

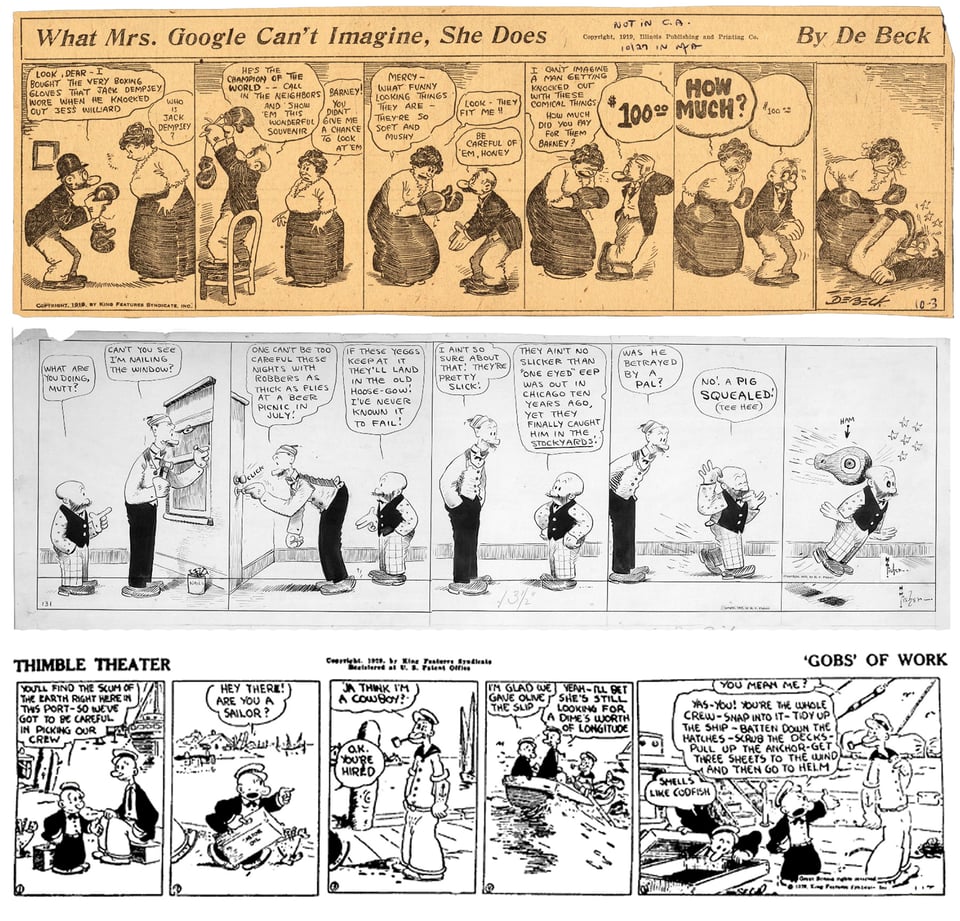

There’s a horrible record of the casual contempt and open hatred expressed towards people of color across the history of comics. Some of the earliest modern-seeming comics of the late 1890s typically sported at least one recurring Black character in a menial position, playing a buffoon, or appearing as an exotic African or other “native” (see “Little Nemo in Slumberland”). Drawings of people seemingly from an Asian nation or of Asian descent were common, too. Their appearances usually had extreme racially caricatured features, expressions, and dialog.

When white characters appeared, they varied enormously, even if they were often grotesque or outlandish. For the dominant cast (or caste!), cartoonists often emphasized a physical element that’s enlarged or shrunken. Consider Mutt and Jeff’s respective heights in their comic strip, the tiny figure of the eponymous Barney Google and his “wife three times his size” in early installments (a line from the same-named song about the strip), or Popeye’s huge forearms from his introduction in “Thimble Theatre.” The caricature builds on pieces of the body or face and, even if cruel, were not racialized shorthand.

There are exceptions: as a Jewish person, I’m quite conscious of this, and you can find it in how Irish, Mexican, and people of other nationalities, religions, and ethnicities suffered parody. This stems in part from how American society absorbed peoples into the definition of whiteness from the 1800s onwards.1 For people of color, however, particularly if Black or Asian, the brutality of depiction was more pervasive and long lasting.

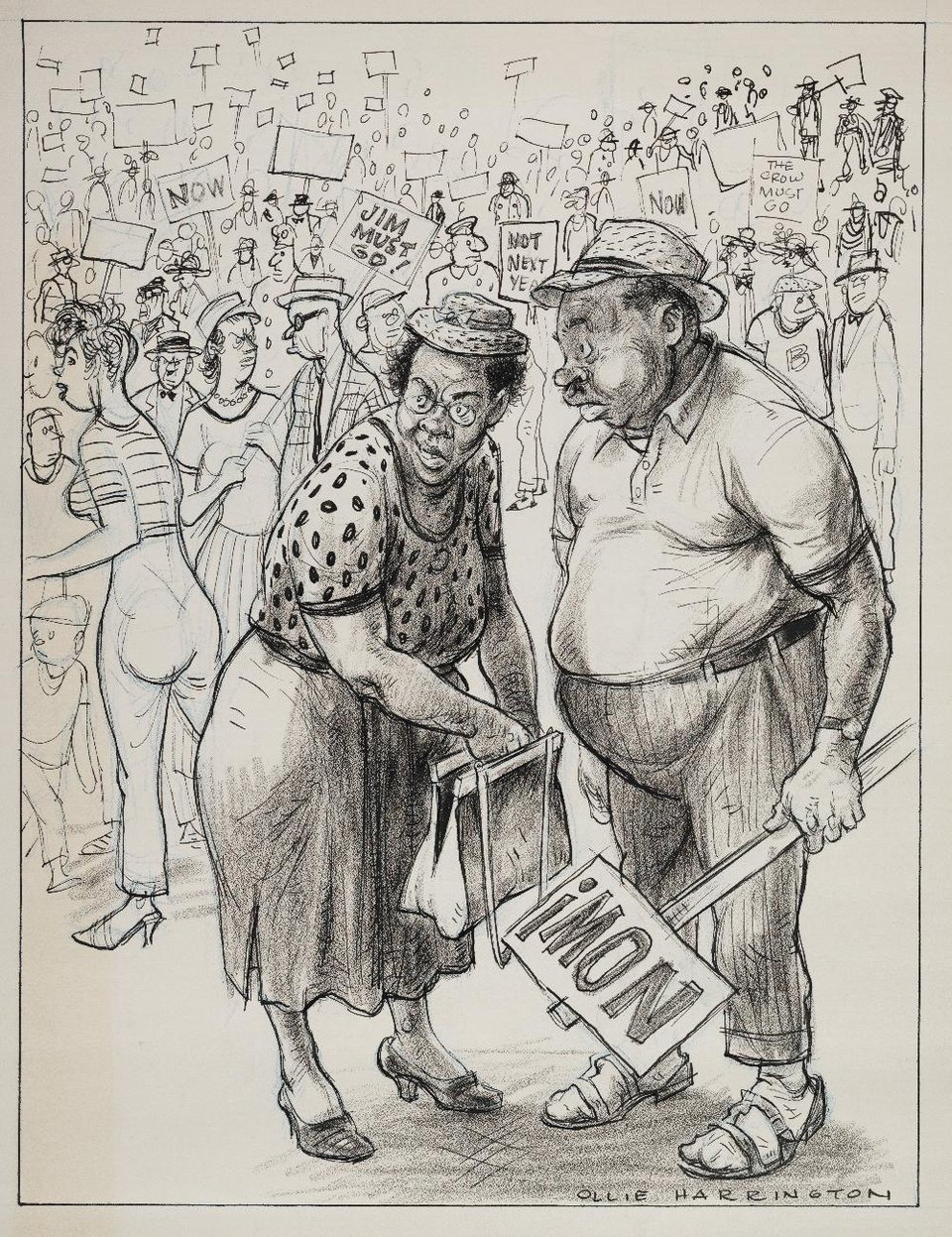

Black characters almost always had a jet-black face with no tone or nuance, huge white lips, enormous eyes, and large bodies—hulking, slouched men and large women. As early Black cartoonist Oliver Harrington (1912–1995) described it, Black characters “were always represented as a circle, black with two hotdogs in the middle of the mouth.”

This style came directly from minstrelsy, among the most popular forms of entertainment in America both before and after the Civil War. White performers made themselves up in stylized blackface and dyed hair. Shows originally featured many kinds of stock roles, including the slave, the “mammy,” and the old uncle; the character people most likely bring to mind, however, is the “dandy,” dressed in tails and gloves, often with a top hat, monocle, and other upper-class accoutrements. (Mickey Mouse was introduced as a minstrel character and retains many vestiges today.2)

Although the minstrel act was in deep decline in the early 1900s, it persisted. The first movie with synchronized speaking and singing, The Jazz Singer (1927), features Al Jolson repeating some of his famous minstrel act. Minstrel numbers continue for an uncomfortably long period of time on stage and in movies, with a notable scene in 1942’s Holiday Inn, usually cut during the broadcast TV era. (The scene features a song for the celebration of Abraham Lincoln’s birthday and is about the glory of manumission, but seeing Marjorie Reynolds casually paint her face black is something else.) Minstrelsy finally fell out of favor by the late 1940s—although as late as 1954, White Christmas features an uncomfortable number with the performers dressed in minstrel style but without blackface performing “I’d Rather See a Minstrel Show.”

As blackface waned in live performances and appeared sporadically but routinely on film, it remained abundant in cartoons. The reason is clear: white audiences accepted or desired these characterizations and white cartoonists fed them—whether they agreed or not. Attempts to show Black and other people of color on equal footing, in integrated environments, or even with less radicalization in their features were quickly dispatched.

Frederick Douglass (1817–1895), writing long before comic strips existed as an art in 1847, offers a key insight. In a short article, he criticized a white Rochester, New York, newspaper owner for denigrating an upcoming performance of the Hutchinson Singers, friends of his and pro-abolitionists: “We believe he does not object to the ‘Virginia Minstrels,’ ‘Christy’s Minstrels,’ the ‘Ethiopian Serenaders,’ or any of the filthy scum of white society, who have stolen from us a complexion denied to them by nature, in which to make money, and pander to the corrupt taste of their white fellow-citizens.”3 One can see white cartoonists drawing Black figures in just this fashion: instead of dressing up and putting on make-up, they let their ink do the performance for them.

It’s worth noting, however, it wasn’t just white artists drawing Black people this way. As the Jim Crow Museum explains in a detailed timeline, Black artists often leaned on these tropes, too, just as there were Black minstrel performers and Black actors who took on minstrel-like roles in films.4

It is true that some cartoon characters had dignity despite all these trappings. Reading “Gasoline Alley” strips from the 1920s, I found that the family’s maid, Rachel—if you ignore the dialect and depiction—has sensible insights she gives to young Skeezix (the adopted son of Walt) and others. She sometimes occupies center stage for an entire strip.5 Sadly, even the small affordances of respect given to Rachel are rare in that long era.

Franklin, My Dear, I Give a Damn

In planning How Comics Were Made, I made the decision to exclude nearly all material with offensive drawings and dialog by today’s standards (as I did in this newsletter issue), as I would need the sensitivity and space to address that, instead of including it in and walking around the issues raised. The book largely looks at the context of comics inside of printing rather than the general content and history of comics.

But as I researched further and spoke to cartoonists, I found a rich area that hasn’t been well explored: the interplay of printing and faces of people of color, particularly in the transition from racial stereotypes to general comic style—when Black, Asian, and other characters are given the same treatment on the page as white ones. Put plainly: how do people of color, given the freedom to do so, indicate characters are people of color?

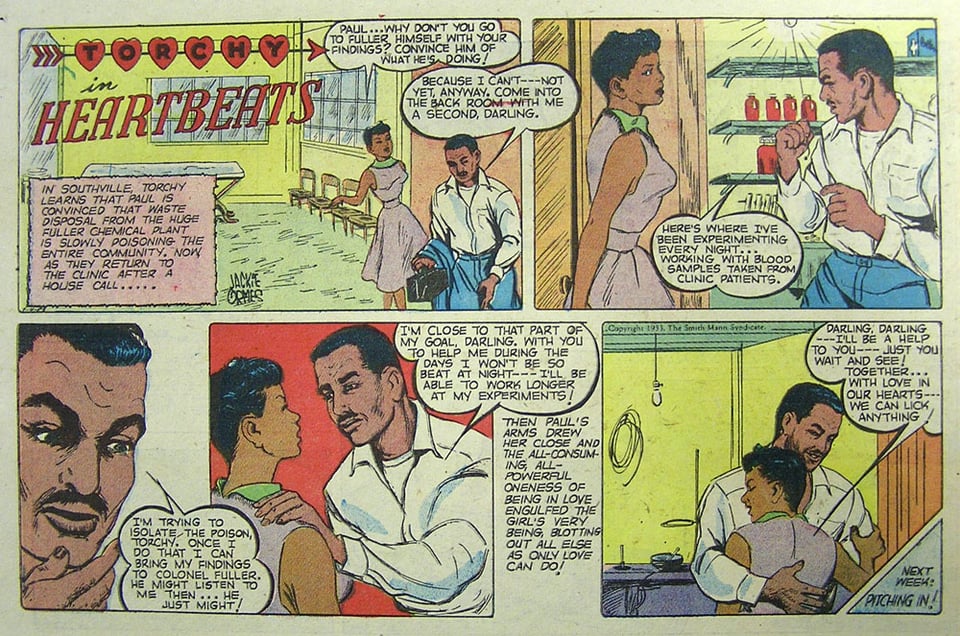

As part of the broader shift from comic racism to comic realism, Black people’s faces, hands, and other exposed skin shifts from 100% black ink in dailies and Sundays, and from strong yellows, reds, and browns in Sunday strips for others: tints and crosshatching combined with less-racially exaggerated features in dailies; more subdued hues that match better against the pink or paler colors of white people. This came as a few Black cartoonists finally achieved national syndication with Black characters in their strips.

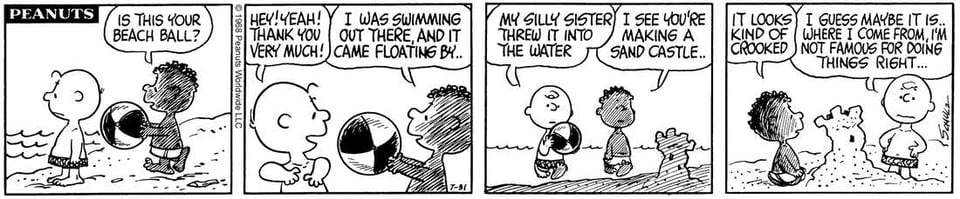

The watershed event in mainstream newspapers—ones created for white communities and which dominated politics and advertising in towns and cities—was the murder of Martin Luther King, Jr. His assassination spurred enormous change in society, though how wide-reaching and long-lasting obviously remains in question. The comics pages weren’t immune from it. Later that year, Charles Schulz (1922–2000) introduced Franklin, integrating “Peanuts.”

Several decades before King’s killing, artists of color were already drawing themselves and their compatriots in non-racially offensive ways, including with varieties of tints and hues. These comic strips and drawing almost always appeared in newspapers, published by and for the Black community or those for speakers of specific languages or from particular countries.

For instance, legendary artist Jackie Ormes (1911–1985) debuted in 1937 with “Torchy Brown in Dixie to Harlem” for the Pittsburgh Courier, a high-circulation, nationally distributed Black newspaper, and created other strips, including a revamped Torchy, for the Courier and other Black papers through 1956. She was the first female Black artist with this kind of reach and lengthy career. She drew realistic figures and faces with subtle tints and colors on often serious topics, such as the cartoon below.

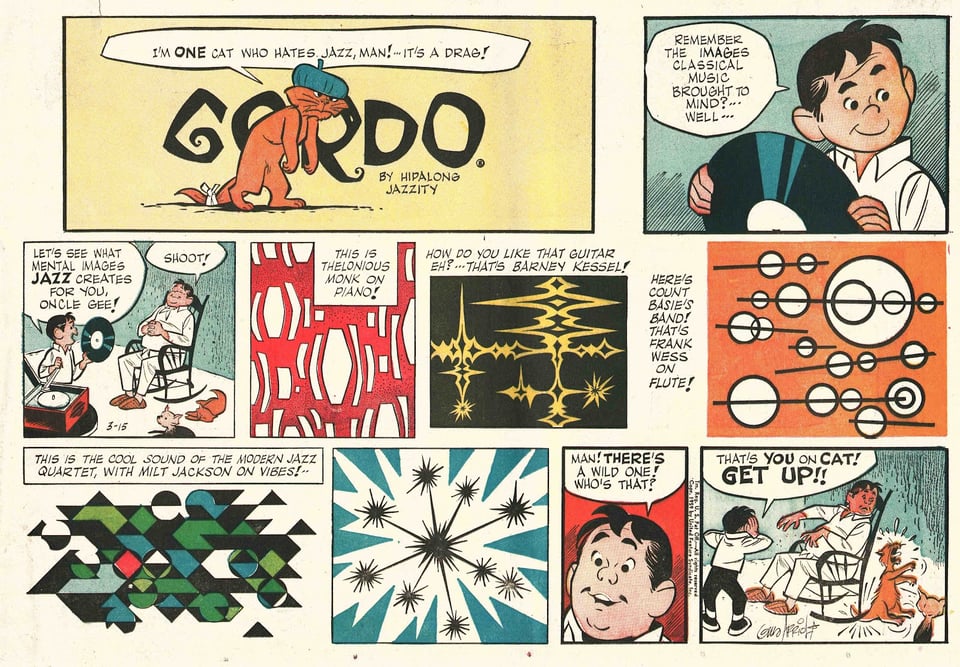

Other cartoonists of color preceded and followed her, creating work meaningful for their locked-in audiences, yet rarely having the opportunity to reach the larger white newspaper reader, with some exceptions.6 A handful of Black cartoonists had syndicated strips at times, but drew mostly white faces.

That began to change with aching slowness in the 1960s. Morrie Turner (1923–2014) broke an integration and color barrier. Both civil rights activists and his friends Schulz and “Family Circus”’s Bil Keane (1922–2011) encouraged him to create a strip drawn from his experience, and “Wee Pals” was the result, debuting in five newspapers in 1965 with an integrated cast of kids of multiple races, portrayed on equal ground. The strip expanded to over 100 papers following King’s murder. After Turner, Brumsic Brandon Jr. (1927–2014) introduced “Luther” (named for King) in 1968 and Ted Shearer’s (1919–1992) “Quincy” premiered in 1970.

A few years after the introduction of his syndicated comic, Brandon wrote in a 1974 essay, “‘Luther’ and the Black Image in the Comics”7:

If there is a joke, there must also be a butt of that joke. We Blacks have been either the butt of those jokes in the comics or totally ignored until quite recently. With the advent of the few Black comic strips that exist today, we have taken a giant step away from being the butt of the joke and another giant step into the position of pointing an accusative finger.

Other Black cartoonists followed, though you don’t need many fingers to count them all. These include Ray Billingsley (1957–), “Curtis”; Robb Armstrong (1962–), creator of “JumpStart” and the family namesake of “Peanut”’s Franklin Armstrong; Brandon’s daughter Barbara Brandon-Croft (1958–), “Where I’m Coming From”; and Tauhid Bondia (1976–), who started in syndication with “Crabgrass” in 2019. Finding artists of color from other backgrounds is a harder row to hoe. Tak Toyoshima (1971–), of Japanese descent, created “Secret Asian Man” from 1999–2013, including three years of daily syndication in the late 2000s. “Gordo” is one of the most prominent Latino cartoons, created by Gus Arriola (1917–2008), whose parents came from Mexico; it ran from 1941 to 1985, an early culturally distinct voice in the funnies.

Opportunities remained scarce, despite the existence of these strips in syndication. Brandon-Croft—herself the first nationally syndicated Black female cartoonist—remembers that her father had meticulous lists of which papers subscribed to his strip, largely because each paper had a different fee set by the syndicate based on circulation and competition. If an opening for a comic strip appeared in a newspaper and “Luther” were suggested, editors would tell the syndicate, Brandon-Croft says, “We already have ‘Wee Pals’ or ‘Friday Foster,’” other Black-penned comics—and they didn’t want two.

White cartoonists increasingly added non-white characters to their comics starting in 1968. The most famous, of course, is Schulz’s Franklin. The story has been well told how a letter from a white woman advocating for a Black character led Schulz at first to reject the notion gently as being patronizing and then, possibly with input from other cartoonists, such as Turner, to add Franklin. Schulz had the popularity and syndicate support to ignore complaints from newspaper editors; it doesn’t seem like Franklin led to any notable cancellations.

It’s here where the story I tell in the book will largely begin: Schulz’s choice of how to indicate Franklin’s race was through the use of cross hatching instead of applied dot-pattern tints. This cross hatching influenced generations of artists, spawned academic commentary, and prompted reader letters. Ultimately, even Schulz moved away from it, while other artists chose different paths. I’ll be writing about this in depth with illustrations of these choices and shifts in How Comics Were Made.

Footnotes

1 See, for instance, Raluca Bejan, “Whiteness in Question: the Anatomy of a Taxonomy Across Transnational Contexts,” Dialect Anthropol. 2022;46(3):347-372. doi: 10.1007/s10624-022-09665-6. Epub 2022 Aug 16. PMID: 35991344; PMCID: PMC9380683.

2 See Birth of an Industry: Blackface Minstrelsy and the Rise of American Animation, for one of many examinations.

3 Douglass, The North Star (Rochester, N.Y.), October 27, 1848, p. 1.

4 For instance, the actress Hattie McDaniel (1893–1952) was literally “Mammy” in Gone with the Wind (1939), a film that celebrated the South, before, during, and after the Civil War. McDaniel performed in a Black minstrel troop early in her career.

5 Rachel predated “Gasoline Alley,” which debuted in 1918, appearing first in creator Frank King’s (1883–1969) “Bobby Make-Believe,” which ran from 1915–1919.

6 George Herriman (1880–1944), creator of “Krazy Kat,” had mixed-race Creole ancestry, but his parents quietly assimilated and he lived his life in the white world, where he was often described as Greek.

7 Freedomways, Volume 14, Issue 3 (Spring 1974), p. 233.

Add a comment: