What Could We Learn From Jordan Neely's Life?

New York Mag Revisits, But Doesn't Reimagine Jordan Neely's Story

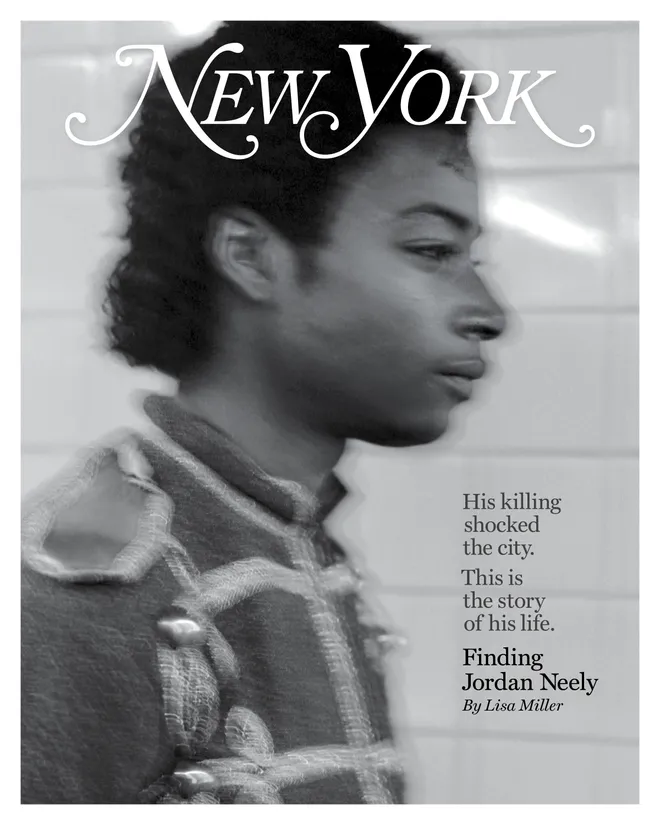

The cover story of the most recent New York magazine told readers about Jordan Neely's life. It was a well-researched and heartbreaking read. I appreciated the chance to get to know more about Jordan through those who knew and loved him. But ultimately, the piece left me feeling disappointed. As Lisa Miller transitioned from Jordan's youth (marred by the tragic murder of his mother) to chronicling the final years of Jordan's life, she failed to reframe our understanding of how multiple systems failed Jordan.

Miller tries her best to center Jordan's humanity throughout the piece, but as she details Jordan's unraveling into mental illness toward the end of his life, she struggles to break away from dominant narratives about unhoused and mentally ill people. When she describes Jordan as increasingly erratic and dangerous, she is being factual. But when describing the people and systems that were responsible for Jordan's well-being, she does so in a way that reinforces carceral logic. The underlying argument seems to be that Jordan was a dangerous person, and dangerous people need to be locked up. A man who mentored Jordan's dancing is quoted as saying, "When he got locked up, that could have saved him."

In the next paragraph, Miller describes the various people who were looking for Jordan after he left a court-mandated treatment facility for drug abuse and mental illness. Miller writes, "But outreach workers don't like the police and are not inclined to work with them, so when [Bowery Residents' Committee] encountered Neely twice in March, he wasn't turned in." She does not quote any outreach workers directly or elaborate on why they don't like the police. Without doing so, this is left open to interpretation. It's easy to read this moment as an indictment of the outreach workers. There could be a myriad of valid reasons outreach workers prefer not to cooperate with NYPD, but readers will never know.

Overall, Miller avoids offering too many direct policy criticisms or prescriptions. She suggests via a quote from a Rikers staff person that Jordan would have benefited from some sort of "secure, residential, therapeutic environment." She acknowledges that this poses an issue because of the civil rights of mentally ill and drug users and does not dig into the suggestion further.

Toward the article's closing, Miller casts doubt on the motivations of social justice activists who showed up for Jordan's funeral: "The Reverend Al Sharpton presided over Neely's white coffin blanketed with roses, and Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, in the front row, stood with her hands in the air, immersed in the call-and-response. After Neely's casket was loaded into the hearse, a crowd on the street holding signs chanted, 'Say his name,' but it wasn't too long before his name was forgotten and the rubberneckers moved on." I can't speak for Rev. Sharpton or AOC, but I read this line as an unprovoked swipe at the people in New York City who were saddened and outraged by Jordan's death and connected it to broader racial and economic injustice. There are many people in this city who have been working to fix the systems and structures that led to Jordan's death. They had been doing it long before the country learned Jordan's name, and they will continue to do it until the work is done. They have not moved on, although they may not run in the same social circles as Miller.

The story of Jordan's life was worth telling because his life was worth protecting, and his death was an avoidable tragedy. Telling his story in deeper detail is an opportunity for us as a city and a country to make meaning of what happened and hopefully learn from our failures.

But the only solution Miller hints at is incarceration. Otherwise, she eschews making any sort of argument. The ending of her article reads as a sort of defeated shrug by recapping events as they happened with little new analysis. A man was murdered on a crowded subway. People took sides. We moved on. Miller's article seems intended to resist this moving on. Her writing drags us back and looks closely at Jordan Neely's life.

She offers little, however, in terms of a clear and detailed accounting of the failures that led to his death. She seems to be reluctant to take a side or to imagine bold changes to life in New York City that might have helped Jordan as a grieving teenager or a mentally ill adult. Instead, Miller leaves the circumstances of Jordan's murder open to debate once again. By doing so, she misses a chance to advocate for meaningful changes that could save the lives of the many others in New York City who are falling through the cracks today. Reading about the people in Jordan's life who loved him helped me grieve over his death anew. When I read about the moments where they offered him a meal, $20, or a bed to sleep, I felt inspired, infuriated, and sad all at once. Because there was no way that their individual efforts could be enough. We need to build systems and infrastructure of care and rethink our stubborn commitment to police and prisons if we want to write a new ending to Jordan's story.

Other Recent Writing

Recommendations for Reading/Listening/Watching

Susan Raffo, "At Least Two Layers of Support: An Anatomy of Collective Care"