The loss we gain from a Thousand Year Old Campfire

It was in there with the other zines,

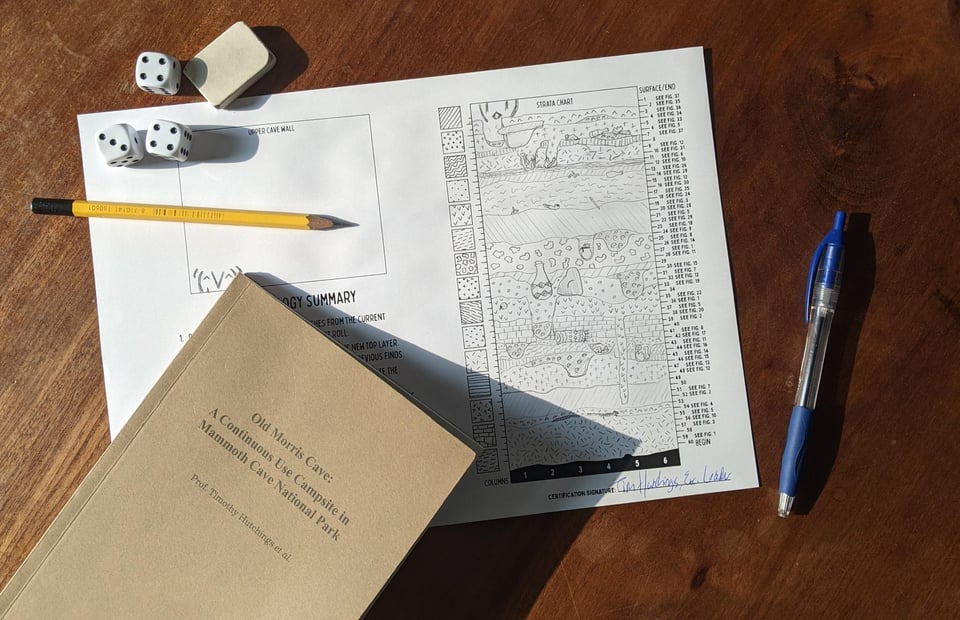

this mud brown booklet. Old Morris Cave: A Continuous Use Campsite in Mammoth Cave National Park, it said in a tidy serif. I didn't notice the name of the author right away.

It stood out among the colorful graphics and maximalist lettering of the MÖRK BORG modules. Inside, it kept its conceit going. It looked just like an academic paper about an archeological excavation. I came upon the graph at the center of the report, a long column titled 'Strata Chart', and I began to understand: I would be drawing the chart of this excavation. That's the game.

It felt fortuitous. I wasn't planning on visiting my local game store, but I did. The zines had been reorganized into a box, which made them easy to flip through. I have a soft spot for academia, so this book stood out to me. And just days before I had concluded that solo games worked best for me if they had a diegetic element—if the game helped me to create something inside the world it opened up for me.

And then I saw that the game was written by Tim Hutchings, of Thousand Year Old Vampire-fame.1

Inverse excavation

Old Morris Cave is a game about time, just like its larger cousin.2 Tim Hutchings actually bills this zine as A Thousand Year Old Campfire on his website. It is—ostensibly—about the excavation of the eponymous cave, a dig through layers of built-up soil and ash to reach the limestone bottom. In actuality, it's about how those layers have built up over thousands of years. (I’ll try to explain why I think that distinction is significant.)

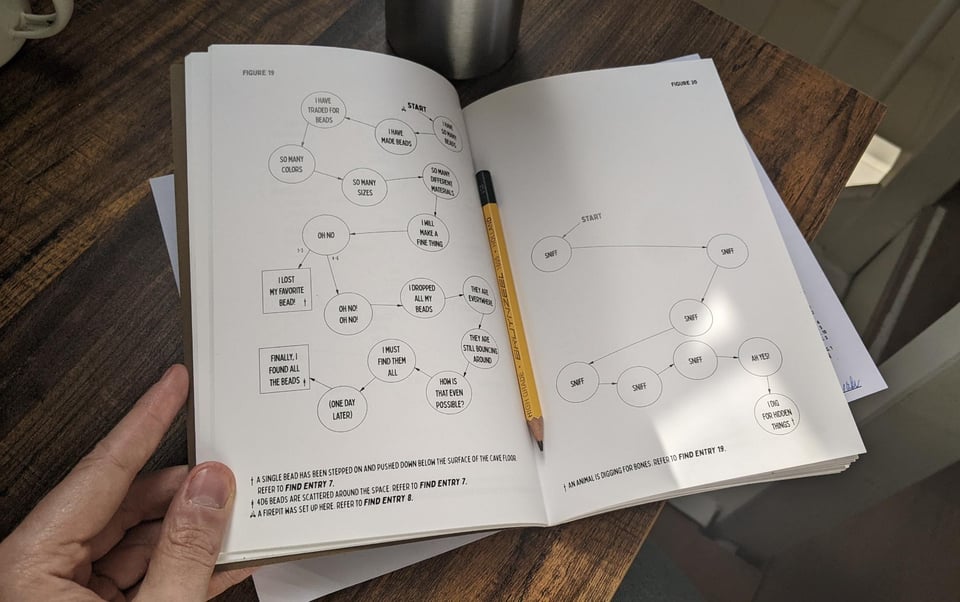

Three elements work together to create that experience. There's the Strata Chart, a big empty box with numbered increments on its long edges. Next come the Figures, which are page-filling flowcharts about all the things that could have happened in the cave. Lastly, there are the Entries: short procedures about the “finds” that populate the strata.

“The game is disguised as a particular sort of regionally produced archaeology journal which I used to see for sale in state parks when I was a youth.” — Tim Hutchings

Each turn you fill the chart with a random new layer of stratum. The chart will then send you to a Figure. There you discover what animals or humans have visited the cave and how they used it. If those visitors leave something behind—their bones, pots or trash—or change the cave in some way—by digging, cleaning, or even by destroying it—the Figure sends you to an Entry. It will tell you how to record the find or what change to make to your chart.

Time's eraser

You draw in pencil. You have to, because you'll erase as much as you'll draw. This, to me, is one of the most important aspects of Old Morris Cave. It is what makes the game more than a simulated excavation. An excavation can only find what hasn't been lost to time; Old Morris Cave allows you to experience the loss.3

The first things I drew were a snakeskin and a snake's skeleton. The animal had slithered into the cave to find a safe place to molt, but, as it turned out, the cave was not safe enough. Several layers later, a new animal dug down for something to eat—and bones would do. You have to understand: drawing those bones felt like a little victory. I created this decoration, this little trace of life. And I wanted them to stay where they were. Instead I was erasing a tunnel through all these layers towards the tiny row of bones. If it reached them, they would disappear. (It didn’t. The animal gave up.)

Much later, almost at the end of the game, I got to draw the remains of an animal that was smothered by the smoke of a fire inside the cave. So I put down a rib cage and a large jaw bone. It was satisfying because I hadn’t had the chance to draw a lot of animal remains, mostly pots and bags. A few turns later, some partying kids dug up the bones and destroyed them. I had to erase them and draw some broken fragments in their place, next to broken bottles and a used condom.

Shades of feelings

There are all sorts of smaller and bigger stories hidden in the Figures’ flowcharts that you unlock by rolling a six-sided die. For example: after the snake slithers in, it might go into hibernation or it might shed. Then it might die in its sleep or at the hand of another being.

Other flowcharts take a bit more effort. There's one about a writer who uses the cave as a residency. It has an early cut-off point if you roll a 1, but if you get past that, the ordeal takes some time to get through—I was almost tempted to cheat to the end, where the writer leaves with a finished manuscript. A footnote tells you the book was published by a 'long-shuttered' press ages ago and only one copy survives at the moment of excavation. It will soon be 'sold for two dollars.'

“A photograph is a nomadic thing that has only a small chance to survive.” — W.G. Sebald

The effort is what makes reaching an Entry all the more satisfying and also what makes erasing your drawings all the more sad and beautiful. The specific contexts even color the feelings of loss in various ways. Some pots were taken from the cave by other visiting natives who lived there for a little while. That little history felt very different from the teens' destruction.

Nomadic things

Moments are fleeting, memories are forgotten, and remains disappear—we know this, but it's an art to offer that fact up to experience. The German writer W.G. Sebald says of the photographs he incorporates into his novels that they 'were meant to get lost somewhere in a box in an attic' before he found them. A photograph, the now rare physical print, he says, 'is a nomadic thing that has only a small chance to survive.'4

Old Morris Cave is full of nomadic things and their survival is provisional. Even the finds that are still there by the end of the game, the objects that are actually dug up, how sure can we be of their safety? The report that records them, a more or less honest attempt to affirm their existence, might have well gone lost. It is, after all, just 'a particular sort of regionally produced archaeology journal which I used to see for sale in state parks when I was a youth,' as Hutchings writes in the description of the book.5

When you reach the top of the Strata Chart, you sign it 'Tim Hutchings, Excavation Leader' and turn the page to read the game's two appendices. The first is an in memoriam for this fictional professor, who died shortly after completing the dig. The second is a review of the report you've just created. It shows a different side to its author and might prompt you to ask if the book was worth saving at all. That's everything I will say about it. You’ll just have to take a chance on the game to discover more. Your time will be worth it.

That's it for now,

Hendrik ten Napel

-

Old Morris Cave: A Continuous Use Campsite in Mammoth Cave National Park, by Tim Hutchings. ↩

-

At the time of writing, Hutchings is actually crowdfunding a sort of sequel to his game. It’s a beautiful collection of collages and prompts that will have you tell the story of someone that falls under the spell of a vampire, called So You've Met A Thousand Year Old Vampire. ↩

-

I think I missed a couple of details in some of the procedures that would have had me erase even more of my chart. ↩

-

This is from an often-quoted televised interview. Here is Nick Warr, an editor of the catalogue of Sebald's found and self-made photographs, quoting it. ↩

-

Still, Old Morris Cave: A Continuous Use Campsite in Mammoth Cave National Park, by Tim Hutchings. ↩