Permission to be tough on your players: in praise of bite

Not to get into social media too much,

but tumblr might still be my number one place for thoughts on role-playing. While preparing this newsletter, I was reminded of an excellent post on Bluebeard's Bride, feminist horror, and how 'to hit—and get hit—really hard and trust that our coplayers were there with us'.1 The post is filled with interesting thoughts on the conditions for controlled but intensely horrific play. You should read it.

Games that are about characters suffering and overcoming obstacles and setbacks—anything from Cyberpunk Red to Lancer to Blades in the Dark—all use different ways to structure that ebb and flow of success and complication. Each gives the Game Master (GM) different rules an permissions to get their players in trouble. Slugblaster, the game I want to talk about today, gives the GM a new tool that I find really effective—but not everyone agrees.

The Game Master’s job

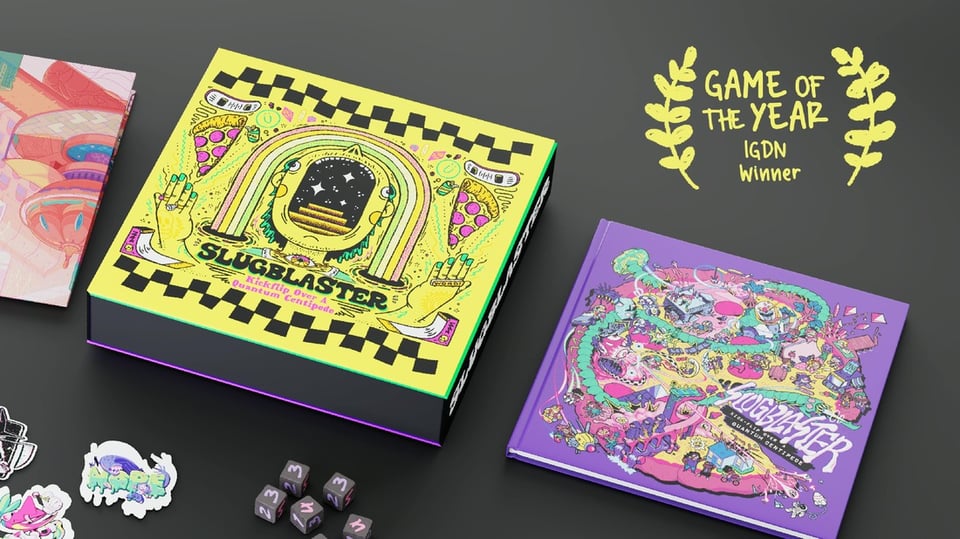

In his review, Quintin Smith had one big point of critique for Slugblaster, a game he crowned as the "winner" of the first season of Quinns Quest.2 What didn't he like? Bite. Bite is a resource for the GM. To quote Smith: 'You can spend bite to trigger bad stuff for the players.' So: setbacks, obstacles, threats and other consequences. Smith then puts forth a much-seen perspective on metacurrencies like these. Namely that they're training wheels:

It's kind of like this helpful little tutorial pop-up for new GMs to put adversity into the story. But not too much! Because you've only got a limited amount of bite.

Smith thinks that 'if you've learned how to GM almost anything else, you will know how to do this already because this is your fucking job'. Like many tutorial pop-ups, these overstay their welcome. This skill is so basic, Smith seems to say, it's unnecessary to bake it into the game's rules.

Looking past how Slugblaster—a colorful action game about teens on hoverboards—might well be someone's first game, I was a little surprised by this take on bite. In the same review, Smith claims role-players and role-playing games are 'broadly speaking' not very good at telling stories. Slugblaster is different: Smith praises the mechanics the game introduces to help players hit a nice three-act arc when narrating their character's personal journeys. Why, then, is Smith so down on a mechanic that does much the same for GMs?

Pacing the story

Bite not only regulates the quantity of adversity a GM can introduce to the story, it also regulates its timing. As in a lot of games, in Slugblaster it falls to the GM to introduce new trouble or opposition to the story after players have rolled the dice. But also, the GM can forgo that opportunity and instead take some bite, basically saving the consequence for a more opportune moment. In other words: bite gives the GM more control over the pacing of the story.

In passing, bite also fixes a known problem with games like these. We could call it 'consequence exhaustion'. Sometimes GMs don't know how to complicate a scene further. Maybe you've asked for a superfluous roll, maybe you aren't interested in the obvious consequence, maybe you just want to keep things going. In Slugblaster, especially, players will sometimes roll just for the chance to pick up style points. With bite, the players get a little reward and the GM get a little more ammunition. Tension rises. How many bite is that now?

Then, when the GM spots the right opportunity to go hard, they erase some bite from their sheet: a monster makes an extra attack in a surge of anger, or the plasma storm builds up speed chasing the players into a climactic finale. If the GM has the bite to pay for it, that implies they've cut their players some slack earlier. Now, they can go as hard as they want.

Permission to go hard

When you roll a six or lower on a Move in Apocalypse World, its text says: 'be prepared for the worst.'3 That is to say: it's the GM's game now. But Apocalypse World also explains that if the players look to the GM to find out what's next or if they ignore a threat the GM foreshadowed, the GM also gets to hit them with a move. Apocalypse World doesn't just gamify the player's side of the conversation, it also give the GM a game to play.4

Structuring adversity not only makes for better stories, it also lightens the GM's load by providing them with something of an alibi. They're not handing out adversity at random: they are using their resources just like the players are. It's allowed. Mikey Hamm, the designer of Slugblaster, says as much in a note on bite: 'I find it helps me worry less and have more fun.'

You will have guessed by now: I like bite.5 When I GM Slugblaster, I have a little bowl of bottle caps somewhere on the table. The moment I spend bite to make an impact on the story, I throw my caps back into the bowl, where they make the satisfying, tinny sound my players love to hate.

Pushing away the ladder

Games like Wanderhome and Good Society make use of similar resource economies to introduce adversity to their stories. In Wanderhome a player can opt to narrate a setback to earn a resource they can spend later to solve a problem. In Good Society a player may offer a resource to another player on the condition they accept a setback—a resource that player can use to negotiate trouble with someone else later.6

In both games, players may find themselves forgetting to use those resources after a while. Wanderhome becomes an organic give-and-take, and the players of Good Society may realize it's not about the resource, but about the negotiation. I like to think of these cases as climbing a ladder. Once you've climbed it, do you push it away? It depends, right? In the same way, I think there's a little more to bite than the guiderails it provides: it's a great narrative tool for a game of overcoming adversity.

But I get where Smith is coming from. If there's enough trust at the table, you don't need the GM to pay a metacurrency to introduce adversity. You'll understand: they are just playing their part. This is what makes the game interesting. But if you ask a game like Archipelago, trust also means you don't really need the dice either, or a GM. Maybe that's true too? Other games seem to create stories without them just fine.

That's it for now,

Hendrik ten Napel

'a game where we hurt each other' by che. ↩

Quinns Quest Reviews: There's a Skating RPG, and it's a Masterpiece, over on the Quinns Quest YouTube channel. Smith has done the hobby a great service with this series, presenting six in-depth reviews of great indie games. ↩

I feel like I might have started referencing Apocalypse World like a preacher would the Bible, but I'll stop once the game has nothing to add to current discussions anymore. ↩

In Slugblaster, that game is resource management. Both the players and the GM have only so much of their respective resources to play with, putting a clock on their current adventure from both sides. Smith makes a positive note of the players' game, but doesn't seem as interested in resource management as a GM. ↩

My game about chambermaids investigating a haunted alpine hotel introduces the GM Move 'Take a coin to pay them back later' which is very much inspired by bite. ↩

Wanderhome, by Jay Dragon; Good Society, by Hayley Gorden and Vee Hendro. ↩