Is every mechanic a prompt? A slightly reductive thought experiment

Roleplaying games are a conversation.

Well, at least, a lot of them are. The Bakers were careful to limit the definition to their game Apocalypse World. But, as it goes with great phrases, the adage got copied to other games that were Powered by the Apocalypse, and Blades in the Dark spread it even further.

Conversations needs stuff to talk about: subject matter. So far so obvious. Well, what if we try to analyze roleplaying mechanics as ways to produce that conversational material. It would mean that, in the end, every rule is essentially a prompt to make players to talk about the stuff the game cares about.

Allocating dice as prompts

In a recent blogpost, Clayton Notestein coins the term phantom cogs.1 It’s a name for rules, mechanics or procedures that don’t relate to the imagined world, its characters or its audience but only to other rules.

The experiment, here, is to see if cogs that do relate to the imagined world and its audience,2 essentially relate to them as encouragement to talk about that world in a specific way. In other words: let’s not bring a game back to its verbs, but to its cues.

Take crowdfunding success Eat the Reich, a game about vampires brutally killing nazis.3 In that game, the players gather a pool of dice on their turn, roll them, discard the failures, and allocate each successful result tot one of five ways to influence the fiction, like attacking a threat, defending from harm, or drinking nazi blood. The rules ask you to narrate each decision:

As you allocate each dice, add one detail that describes the scene as it happens. If those details satisfy new bonus dice conditions on the equipment or abilities you’re using, you can roll those bonus dice at this stage.

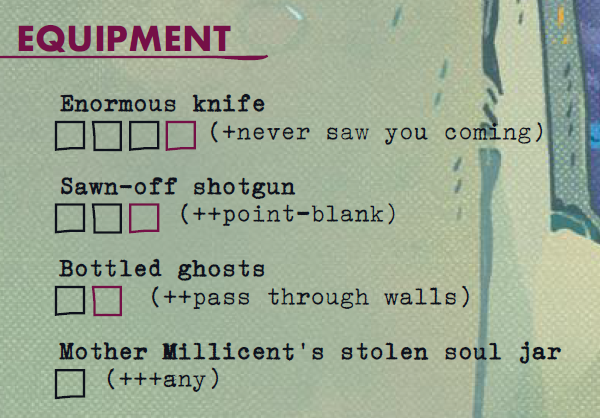

Each allocation amounts to a prompt. Those bonus dice conditions? Subprompts! Take a look at the equipment list of one of the vampires:

Each of those weapons and tools is a prompt, and the bonus conditions—those with a plus in front of them—motivate a player to take those prompts in more specific directions.

Resolution mechanics as prompts

I think Eat the Reichs use of prompt-like material is already really interesting, but lets try a more heavy-handed reduction to really drive this thought experiment home: resolution mechanics.

Saves in Mausritter, a game about adventurous mice, could be redescribed as a way to produce prompts.4 ‘When you describe your mouse doing something risky where the outcome is uncertain and failure has consequences,’ you roll a d20. If the result is equal or lower than the associated ability score, you succeed and describe your success. If you roll over that number, your mouse fails, and the GM describes the consequences.

In terms of prompts, a Save is there to produce one of two. While not prompting you directly to narrate risky actions—Mausritter’s premise and equipment encourage you to do that—when it does happen, the game either prompts the player to narrate their success, or the Game Master to narrate failure and consequences.

Other games add more prompts to a moment like this. Sticking to adventure games, World of Dungeons5 adds two more prompts: narrating succeeding at a cost or success with an added benefit. The prompts become less binary and the narration can go in slightly different directions, but the game stays interested in that moment of tension and the degree of success.

Is this helpful?

I’d like to dispel any notion that I’m trying to unearth the atom of game design here. I’m interested in what this experiment can tell me about the stories I’ll tell when playing a certain game. What do certain Stats in Apocalypse World, like Cool or Weird, prompt you to narrate? What about marking Stress in Blades in the Dark? And mechanics that don’t prompt narration, how do they look in comparison?

In order to help you describe big action sequences, Eat the Reich has you narrate several specific moments in succession, prompting you with options, equipment, abilities and bonus conditions to further those scene in specific, high-octane directions.

Mausritter seems to pale in comparison, but only when you look at Saves in isolation. Reading the player advice on the same page, you’ll see that the game discourages you from triggering a Save if you don’t have to:

Dice are dangerous. Clever plans don’t need to roll.

The resolution prompt is right there, but the game tries to dissuade you from answering it. Instead, it says, you should narrate different actions—if you want to live. This begs the question: how does Mausritter prompt players to talk about those clever plans instead of risky actions? Wouldn’t you like to know?

Bye for now,

Hendrik ten Napel

Phantom Cogs, by Clayton Notestein over on Explorers Design.

True Cogs? Actual Cogs? I’ll leave the coinage to Notestein.

Eat the Reich, by Grant Howitt.

Mausritter, by Isaac Williams. Also, the description of the Saves rule reminds me of a Powered by the Apocalypse-style Move, up the a trigger phrase and the distribution of narrative authority. That’s just something I found interesting.

World of Dungeons, by John Harper.