Interesting experiences of player agency in non-canonical mysteries

“It feels like we’re just framing someone.”

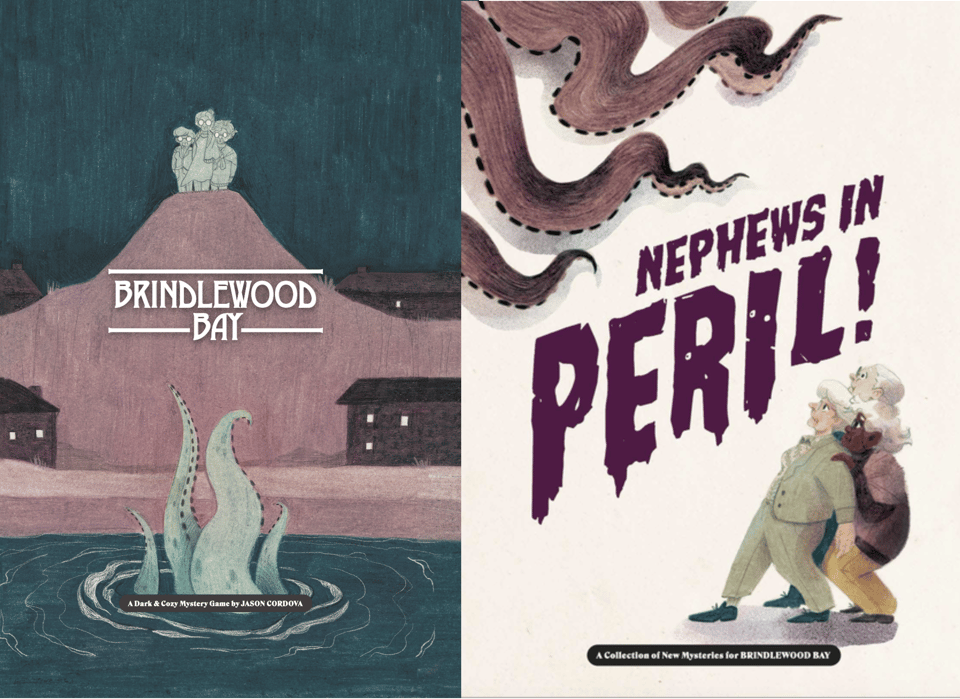

I've come across this sentiment several times while reading about the mystery system in games like Brindlewood Bay and Apocalypse Keys.1 If you're not familiar: the mysteries in those games do not have a canonical solution. Instead, the players gather clues, propose a theory, and roll the dice to discover if their theory is correct. There is no pre-existing truth to uncover, instead, truth is written at the table. And, to some, that feels like the suspect isn't discovered, but "framed".

I don't share that experience, but something happened that made me understand it a little better. I've been writing a Brindlewoodian game of my own, and during playtesting, the process of theorizing stirred up some interesting emotions. The players were deciding on a truth, but one they would rather not confirm.

Framing bad people

In his adaptation of the Brindlewood Mystery system, Mynar Lenahan capitalized on that experience of framing the suspects. The game is called Let Justice Be Done2 and it does feature canonical answers to the whodunnit of it all—they're just not the point of the game. Instead, the custodians you play as pin the murders on billionaires to further their agenda of socialist justice.

To make that work, Let Justice Be Done changes two things: the presentation of the mysteries and the questions associated with the mysteries.3 Those are two of the staple ingredients of a Brindlewood type mystery: the instructions on how to present it to the player and the questions their theory should answer. In this game, Lenahan takes great pleasure in showing you a cut-and-dry case—you know exactly who did it. But then, the questions ask why the surrounding rich assholes might want to kill the victim, and how they did it, together, those lothesome fatcats.

These are small tweaks, but they really change the perspective of the game. Now you're a con man, gathering material for your grand lie, while keeping the law from finding out what really happened.

Ending your friend

In The Girls of the Genziana Hotel4, the game I'm writing, you play as chambermaids in a nineteenth century alpine hotel. After your friend Marga goes missing and the head of staff tries to cover it up, it's up to you to figure out what happened to her. That's the first question you're answering with the clues you gather: "What did they do to Marga?" After my playtesters found six foreboding clues, they had to form a theory to answer that question.

The Girls of the Genziana Hotel is partly about incomplete grief: Marga is gone, and the girls fear the worst, but the ambiguity has also blessed them with ignorance. Now, they're talking about what happened to her, and the clues seem to point to a terrible fate. One player opened up and confessed she had hoped Marga would have survived somehow. Another player agreed, and said: "It feels like we're killing her."

I wasn’t expecting it to feel that intense. While I did design the Question, clues and other aspects of the game to give rise to increased feelings of grief, I hadn't anticipated this experience specifically. But it makes so much sense: in that moment of theorizing, the players are making a decision. If the roll goes their way, Marga is now unequivocally dead.

Like their characters, they might have preferred to keep looking. Like their characters, they need some kind of closure.

Matters of player agency

I know some of the criticism leveled against the Brindlewood mystery system has been interpreted as a misunderstanding of its writer's room approach to roleplaying. You're not framing someone, you're writing the ending to the mystery story you're discovering together. It always felt like that to me, too, but I think I understand that piece of criticism a little better now.

What's more, I now think it might betray an interesting aspect to the mystery system. Lenahan, for one, took the criticism seriously, and designed a game around it, capitalizing on the how much agency the players have while telling these stories. I feel like I've stumbled across another way in which this form of player agency can evoke very specific emotions, which, in some cases, is a great bonus.

That's it for now,

Hendrik ten Napel

It was originally presented by Oli Jeffery in Codex—Moonlight and then iterated upon by Jason Cordova, the writer of games like Brindlewood Bay and The Between. ↩

Let Justice Be Done, by Mynar Lenahan. ↩

Having the players answer a specific question is one of the ways in which I believe Cordova iterated upon Jeffery’s initial proposition. ↩

The Girls of the Genziana Hotel, by, well, Hendrik ten Napel. ↩