Failing when it matters—some innovations in cinematic action games

I, myself, hardly failed:

my piece on Tim Hutchings' Thousand Year Old Campfire got second prize in the review category of the Bloggies. I'm happy to get noticed this way after less than a year of blogging about role-playing games.

The Bloggies also got me reading more widely. Since this initiative basically started out as a thing among Old School Renaissance (OSR) bloggers, it brought me into contact with a lot of subjects important to them. Chief among them: death.1 It's been interesting to see writers wrestle with the idea of death as the ultimate stake. One blog says OSR games aren't as lethal as people say: they're honest about consequences to emphasize player agency.2 Putting death on the table makes choices matter.

Knight at the Opera recently took the position that death isn't necessarily the ultimate consequence, and proposes it could well be replaced with defeat.3 This would allow for 'consequence-driven games where player failure is very possible' without 'consequences so dire' that players approach every encounter with a ten foot pole. Interestingly, even if these bloggers can't seem to agree about death, all these blogs do seem to agree that the risk of failure is necessary.

Which seems to be an assumption a lot of games share, even beyond this particular renaissance. Maybe that’s why John Harper's Deep Cuts made such an impression on me: it redefines the role failure might play in our stories.

Assumed success

Those familiar know Blades in the Dark's Action Roll uses the classic three-tier spread: miss, success with a consequence, and full success. 'On 1-3,' says the text, 'it's up to the GM to decide if the PC's action has effect or not', but 'usually, the action just fails completely'.4 The competent criminals you play in this game can still miss their mark.

Since the game's release in 2017, its creator has reevaluated the use of failure. 'Lots of stuff changed in the action system as I've tweaked and modified it for my Blades games over the years,' writes Harper in the design commentary to Deep Cuts, a supplement full of new lore and rules.5 One of those changes is the Threat Roll. This new resolution mechanic no longer determines if your scoundrel's action succeeds, it assumes it does. Instead, the result of your roll determines what that success might cost you. Do you get hurt along the way? Do you raise suspicion? Do you make an enemy?

The Threat Roll also demands that the GM define the possible consequences—or, you know, threats—beforehand. And only as a threat might failure be reintroduced to this procedure. Harper's own example for this is hitting a small target at a very long range: 'You're not in danger, but I'm adding the threat of failure. You might miss!' It makes sense, right? That's exactly what would be at stake for that action, but not for every action.

Surviving your ambitions

I've been playing in a Deep Cuts campaign for a couple of sessions now, and I've noticed how this reorientation emphasizes some of the core themes of the game. Blades in the Dark has always been about the slow accumulation of stress, harm, suspicion, heat, enemies, and, eventually, trauma. But in this new paradigm—a word I'm not using lightly—my gruff Skovlan Bloodculler will get what she wants, mostly, she'll just become unanchored from material reality because she's fucking with the ghost field to get it.

'How long can I keep doing this,' I find myself thinking as I take stock of Freja's stress and harm. And isn't that exactly what Blades in the Dark is about? The toll of a life of crime? Deep Cuts shows Blades didn't need its actions to 'fail completely' to tell that story: it already has stress, harm, and trauma.6 Right now, Freja is planning to set up the Gondoleers so they get into conflict with the Red Sashes, and she needs to hunt down Bazso Baz, who is presumed dead. She'll make those ambitions a reality if she wants to, but she'll probably lose some parts of herself along the way.

Choosing to fail

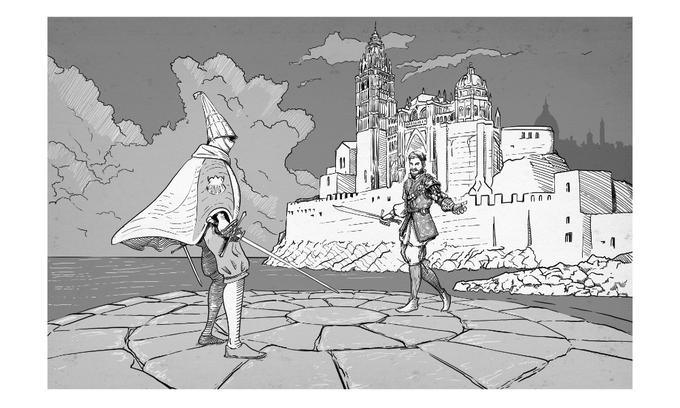

While Harper was tinkering away at Blades in the Dark, Eric Farmer and Eli Kurtz were working on a cinematic action game of their own. It's called Sword Opera and it's inspired by a host of melodramatic stories of violence and tragedy, anything from the Three Musketeers to John Wick.7 Reading through the ashcan I saw that Farmer and Kurtz had come to much of the same conclusion as Harper. Their game didn't need tiers of success for its action mechanic, it needed tiers of abrasion.

On a 1-3, 'things go poorly.' But you don't have to fail. 'You can still choose to achieve your objective,' says the text, 'but the consequences are severe.' Unlike Deep Cuts, Sword Opera puts the choice of failure into the hands of the player, not the GM. Because if those consequences aren’t stomachable, the ashcan says, 'you may choose to make your paragon fail at their action and replace every consequence with a single lost opportunity'. You give up on your current approach and the GM describes how it has become impossible. If you still want to get past this obstacle or acquire what you want, you'll have to come up with a new plan.

Kurtz told me they wanted failure to be like: 'your paragon could accomplish that goal right now, but they choose to abandon this attempt because it's more important that they save their friend.' To achieve those moments of drama, the consequences have to be put in front of the player so they can feel forced to make that choice. Here, the story is not only about what success might cost, but about why you would choose to forfeit your success for the things that actually matter more to you.

Defaulting to failure

This might sound a little effusive, but I think Deep Cuts has really elevated Blades in the Dark. The original could still be mistaken for quite a traditional game, but the Threat Roll hones in on its themes by refusing to default to failure. That's what it looks in retrospect, doesn't it? Like we assumed you'd need failure for success to mean anything. But no, you can tell an interesting story about the consequences of your success without failing a single time.

In the same sense, giving the player an option to back out of the consequences of those actions creates an opening for yet other stories. Stories about powerful characters that only fail because circumstances force them to let go.

Getting back to my preamble, let me be clear: I’m not advocating for an OSR without failure. I know far too little about the play style to be handing out advice. Then again, if ‘clever plans don’t need to roll’, as Mausritter says, that almost implies a utopic session where dice never hit the table… Would that—no, better read up on the smart ideas of people more versed before I start ideating in a vacuum.

That's it for now,

Hendrik ten Napel

-

I won't get into that here, since more experienced and knowledgeable writers have discussed this extensively already. ↩

-

The Myth of OSR Lethality, by Mythic Mountain Musings. ↩

-

Defeat, Not Death, by Knight at the Opera. ↩

-

Blades in the Dark, by John Harper. ↩

-

'Blades is clocks all the way down,' is a thought that comes to mind here but must be suppressed if I am to focus on the subject at hand. ↩

-

At time of publishing, Sword Opera is crowdfunding a full, physical edition, with about nine days to go. ↩