A stage instead of a cage—The Last Caravan has a friction problem

‘What does this game offer me,’

asks Jay Dragon, ‘that I couldn’t achieve by playing make-believe with my friends?’ This is from her great blogpost about role-playing games as enjoyable cages1 in which she puts forth the thesis that a role-playing game’s rules aren’t there to give us options—it’s make-believe, you don’t need permission to imagine anything. Instead, rules create ‘moments of inefficiency’ that shape how players behave. In other words, friction that pushes play into interesting, maybe unexpected directions.

Of course, not all friction is enjoyable, and Dragon sees this. Part of it is personal preference, but beyond that, games should promise interesting calibrations of restriction. Struggling within their limits should push you towards experiences you couldn’t just as easily, or even more easily, have imagined yourself. Designing games is, in a way, the practice of fine-tuning those limits.

A post-apocalyptic road trip

Viewing design as calibration, The Last Caravan by Ted S. Bushman supplies us with an interesting case.2 Facilitating a campaign, I quickly started to notice how the table felt both restricted and lost at the same time, but it took me a little while to understand how we kept ending up in that position. I think now that this experience has a lot to do with how Bushman adapted Blades in the Dark’s rules for his game and recalibrated its limits.

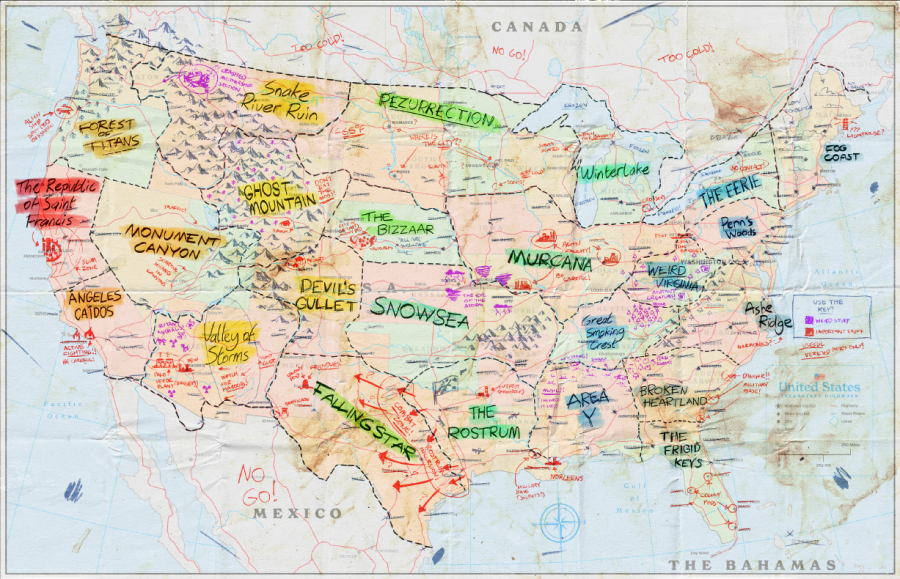

As per its tagline, The Last Caravan is ‘a cars and aliens roleplaying game’. I’ve always introduced it this way: what if The Last of Us was about an alien invasion instead of fungal zombification. Two months of war with intergalactic visitors has filled Earth’s atmosphere with debris, casting a shadow over our planet. During the resulting winter—the coldest and longest in a hundred years—a car full of survivors, the titular caravan, will make a desperate road trip across the United States’ weird and war-torn landscape.

Those are a lot of great ingredients. A post-apocalyptic winter road trip? Are we finding our family along the way? Say no more.

From heists to detours

I thought adapting Blades in the Dark sounded like a good approach. Going by the pitch, The Last Caravan should basically be broken up into two types of scenes: dangerous confrontations along the way and interpersonal drama between the protagonists. Blades in the Dark’s mission structure, in which the characters perform a heist or an assassination and then deal with the aftermath during their downtime, maps nicely onto that rough division. Then why does is not quite work?

Let’s take a closer look. The Last Caravan breaks up the travelers’ journey with the detours they go on, usually at a cost to deal with once they’re back on the road again. Detours are about danger, however they are approached. The dangers of sneaking around alien wildlife to look for supplies in a mall or the dangers of saving an old couple from their house by the seaside while space crafts out in the ocean start moving again.

During a detour, players roll the dice to see how they move past obstacles or deal with dangerous threats. The Last Caravan uses Blades’ dice pool of one or more six-sided dice with three possible outcomes: failure, success with a consequence, and a clean success. It’s a great choice, although some of the minor issues this resolution mechanic already has are a little more pronounced in The Last Caravan.3

As an aside: I am surprised Bushman left position and effect on the cutting room floor. Blades uses this conversational tool to establish how dangerous and impactful an action might be—quite useful for a world in which threats range from desperate hitchhikers to alien shock troops.

When the travelers get back in their car and start driving again, the players get a chance to perform some downtime actions and frame free-form role-playing scenes to hash it out between their characters. You make repairs, experiment with alien tech, and confront your ex-boyfriend about how he endangered the whole caravan by attacking that wounded alien.

Estranged and reluctant

Getting from those downtime scenes into a detour is where problems arise, and this has everything to do with The Last Caravan’s setting and intended narrative. Blades in the Dark takes place in a single city that the characters already have contacts in and which the players get to know session by session. Starting with the nature of their criminal organization, the players have plenty to go on when it comes to figuring out what score they’d like to pursue. In short, the characters are embedded and intrinsically motivated.

The Last Caravan suggests a couple of group dynamics for bringing together your caravan. The default is ‘Kin’: a ‘family, blood-related or not, with shared history and shared problems.’ The caravan has two reasons for heading west: the news of a large, fortified city and signs of activity from the alien powers in the east. The group then decides on a moment that instigates their journey, ‘a unique or personal reason’ for getting on the road, which should also connect them to the aliens.

And so the journey begins, leading from the east coast through several uniquely weird locales towards post-apocalyptic California. Surroundings constantly change and the landscape has been radically altered through war, winter, and alien technology. The detours are aptly named: they are deviations from a journey towards a safe haven. Why would the travelers go on one?

Instead of embedded and motivated, the caravan is estranged from its surroundings and reluctant to stray from the main road, since their main motivation is to get away to somewhere safe. Whereas in Blades the players take the lead, supported by things like contacts, faction relations and their growing familiarity with the setting, in The Last Caravan it’s up to the GM to lure the caravan into action.

Structural problems

‘How do you find detours?’ You, here, are the players. This is The Last Caravan’s answer:

You might have a map. Characters in the world might tell you about landmarks or places of significance. You might be asked favors, or your own stories might lead you somewhere. If you’re uncertain, ask [the GM] about some destination in the area.

The question implies they are actually looking, but if we take the characters’ instigating motivation seriously, the caravan is mainly interested in two things: fuel and supplies. Since both of those can be gained during the travel phase too, they will only now and then lead to a detour. Most detours will be options presented by the GM, who’ll put landmarks on the map, stick signs by the road, insert quest-givers into the narrative, trigger disasters, and foreshadow an ambush.

The Last Caravan is aware of this problem. In the GM’s section of the book about a page and a half is spend on the question ‘how can I get players to buy into regional conflicts?’ If your players are just trying to survive, that’s great ‘player expression’, it says, but as a GM it 'might make you worry.’ How do you bring the caravan into contact with factions, developments in the world and interesting mysteries?

The advice given is credible, if a little sparse: ‘Create mystery, promise discovery’, ‘Involve characters they care about’, ‘Offer rewards’. Good advice or not, it doesn’t quite solve the contradictory position the game puts its players in. That problem is more structural. There’s a big blank at the heart of The Last Caravan: not enough of its limits push the players into the exciting, dangerous scenes the game would like to see them in. They kind of have to find their way there themselves.

The hero’s journey

Several factions, plots and mysteries are at play in the devastated States of America, and The Last Caravan wants you to become entangled with them. In the end, this is why the game needs the caravan to deviate from its journey to the west. I can definitely see why: Bushman and his guest writers created twenty-three ‘regions’ full of interesting stuff.

To motivate the caravan to engage with those regional conflicts, each of the regions comes with a ‘Way Out’. This is a ‘narrative requirement’ that needs to be met before the caravan can cross the border to enter a new region. ‘The Eerie’ requires the caravan to ‘rescue the remnants’, a group of hostages captured by rogue alien soldiers ‘pushed over the edge’. ‘Snowsea’ requires the caravan to ‘deactivate the terraforming engine, repurpose it, or entrust it to a faction’.

Uncharitably, you could say the game traps the protagonists in a region until they become the heroes they’re supposed to be. Each Way Out puts a serious limit on the players' directions to role-play in, and I don't think it's the right one. (Also, I found I had to improvise how to implement the requirements, as I couldn't find a specific instruction. I've assumed the players should know explicitly what the narrative required of them each region, as a kind of prompt for meta-gaming.)

Bridging a gap between your character’s initial motivation and a clear narrative goal can be interesting, but in this case, I think the rift is too wide. Again, the game’s search for friction gets stuck in a contradictory position. This time, The Last Caravan wants to be both a sandbox and an adventure module. ‘The Last Caravan’s themes and setting could fit a number of possible experiences,’ says the book, but looking at the Way Out, it seems like there’s a pretty specific story these experiences should eventually turn into.

Local heroism

Moment to moment, The Last Caravan prompts its players more effectively. Each character has a reserve of heroism which they can spend to add extra dice to their rolls. They regain that resource by narrating actions or scenes that answer to prompts particular to their archetype. For example, the ‘Wrench’ playbook may gain heroism if they ‘improvise using materials on hand’, the ‘Bruiser’ when they ‘protect another traveler from danger’.

Any character may gain heroism if they ‘make things worse’ because of their ‘inadequacy’, which is basically a character flaw chosen at the start of the game, like ‘detachment’ or ‘regret’. It’s a great alibi for players to get their character into more trouble once things get going, taking the onus of the GM.

More extremely, characters risk their inadequacy taking over completely if they take too much harm. One of my campaign’s most memorable moments occurred when a completely detached traveler calmly took up a gun and shot an aggressor in the face, creating an intense turning point in the confrontation.

Heroism was inspired by Belonging Outside Belonging games like Wanderhome and Dream Askew. In those games, players receive tokens when they play towards complication, tokens they may spend to solve problems later on. I wonder if, in another timeline, there’s a version of The Last Caravan that is even more thoroughly inspired by those designs. Is that the more bespoke game The Last Caravan seems to desire to be at times?

Using the game as a stage

‘Remember that The Last Caravan is about normal people finding heroism under extraordinary pressures,’ reads the first chapter of the book. ‘They aren’t heroes—yet.’ Internalize this assignment fully, and you can probably get past most of the problems I’ve described. You’ll think of a reason to make that left turn, and when you hear about an organization called ‘The Answer’, you’ll be suspicious at first, but once you learn more, you’ll see why you have to aid their cause.

Players willing to use The Last Caravan as a stage instead of a cage can definitely tell the game’s intended story, following their internal GPS through every detour they need to go on. The question is: what use do those players have for the game? I’m afraid they would find it to have a lot more rules than they need. If you know where you’re going, a coin flip now and then could get you there.4 If you don’t, and you’re interested in submitting yourself to a game, you are going to need a fitted cage.

Fortunately, Bushman is publishing an expansion to The Last Caravan. It’s called The Lost Highway, and I hope its ‘tools to make running the game even better’ address some of the issues I’ve described.5 I really do, because there’s a lot I do like about The Last Caravan. Bushman’s idea for song-based technology, for instance, really sets the aliens apart in a beautiful, otherworldly way. So, come September, I’ll be sure to check it out.

That’s it for now,

Hendrik ten Napel

PS, my gothic horror mystery rpg is coming to Gamefound.

Reserve your room in the Genziana Hotel today.

Rules Are A Cage (and I’m a Puppygirl), by Jay Dragon. ↩

The Last Caravan, by Ted S. Bushman, which has been nominated for the 2025 Ennies. ↩

How many dice you roll is determined by how many points your character has in the 'gambit' that best fits the description of the action they are performing—it’s the same in Blades in the Dark. That precursor already struggles with moments in which it’s unclear which of its categories of action applies to the roll. The Last Caravan’s tailor-made categories—‘Drive A Car’, or ‘Fight Under Pressure’—risk exacerbating this problem. Players at my table regularly felt like they only had a couple of precision tools in moments they needed general capabilities. ↩

Or, for example, a set of conversational tools and a randomizer, like in Archipelago. ↩

It’s actually two expansions. The other one, Westward Bound, provides rules to play as a caravan of animals, a homage to the 1993 classic Homeward Bound. ↩