Hello everyone! My writing life at the moment is revision and more revision. I finished my second draft of Secret Novel and sent it off to its editor. Now I’m tackling the editorial feedback on Mercutio.

(I did some back of the napkin math the other day and realized that once these two books hit the shelves, I will have more than a million words of published fiction under my name. A million words! That is bonkers. And that’s just the published stuff, and doesn’t include interactive fiction. I still feel like I’m just starting out.)

Between these two novels, edits and revision are going to be my main fiction work for the next few months.

But as I’m also in the brainstorming phase for the next novel after that, I’m diving into research. One task at the moment is a very physical one: I maintain a shelf that is just for the research books for current works in progress, and it needs an overhaul as I move on to the next things.

This has got me thinking about what makes a good non-fiction book for me. (As with fiction, non-fiction that works for one reader might not work for another.)

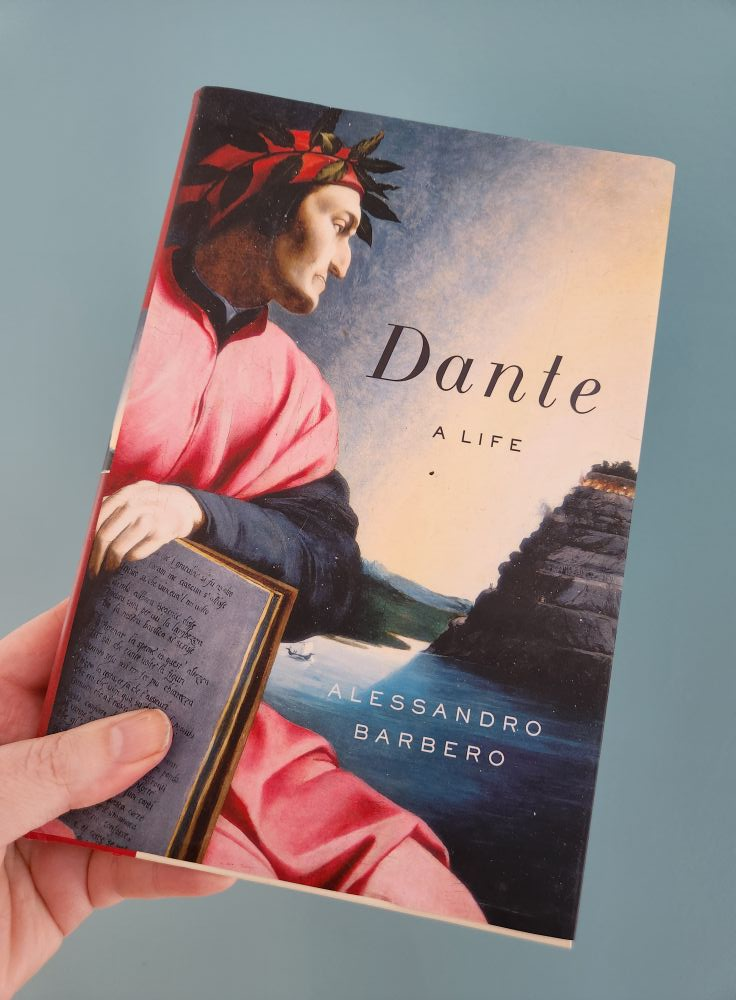

I own three biographies of Dante Alighieri, and I read them all in preparation for writing Mercutio, in which Dante is a major character. They’re all fine, but Dante: A Life by Alessandro Barbero is so good that it became my Dante bible.

I had not read Barbero’s other work before I read this, although an Italian-speaking friend (and beta reader for Mercutio) tells me he has a great history podcast. Not being a historian myself, I have no idea of where his research puts him in the field, or anything like that — I’m coming to this purely as a lay reader. (Maybe not your typical lay reader, given that I’m a historical fiction writer, but a lay reader nonetheless.)

What made this biography stand out for me was the respect for the reader. Barbero lets us in on his analysis and explains all his sources (in a highly accessible way) so that we understand where his narrative comes from.

When discussing the Alaghieri/Alighieri family’s social status, for example, he mentions a documented legal dispute and then moves into this: “According to Enrico Faini, who has recently been studying these controversies, this is sufficient to demonstrate that Alaghieri must also have enjoyed high social status. Can we be sure that is the case? The only other document in which Alaghieri appears is…”

Concrete information about context, nods to current scholarship, references to particular sources, yes, yes, yes! This is how you let the reader in. If I want to follow any of these threads myself, now I can do so.

This approach also helps the reader situate a book within the scholarship of its time and place, since we’re often reading popular history books years or decades after they were written.

It reminded me of an argument I had with a professor 24 years ago. As part of my master of journalism program, I was taking a graduate history seminar as an elective. It was a great course, but one of the assigned books (a popular history book) grated on me and on another classmate, who was also a journalism grad student. One day we chatted with the history prof about why we didn’t like the book, and tried to explain that it gave the reader no sense of where the information came from. She was gobsmacked. “I never thought journalism students would come to me asking for footnotes!” (We sometimes encountered a little bit of an attitude in our “more academic” electives.) We tried (I’m not sure successfully) to explain that it wasn’t footnotes we wanted, necessarily, but just to be privy to the author’s analysis, rather than to be fed assertions presented as unquestionable and unchanging. At one point, I remember one of us saying, “We’re journalists! We don’t trust anybody!” (I actually do want footnotes, too, when I can get them.)

Barbero’s well-paced, fascinating biography left me with an informed opinion on how many children Dante might have had and what year he was married in — and most importantly, an understanding of why those are not settled questions. Some of the other biographies and articles I read just told me, as fact, that it was like this, or it was like that, sometimes with a “probably” thrown in.

Another factor in choosing the right non-fiction book for the right reader is calibrating the focus. If it’s about a place or period I have already read a lot about, I can be frustrated by long sections explaining the big picture in the broadest of terms. But when it comes to periods or aspects of history with which I’m less familiar, or other kinds of non-fiction such as science, those can be appropriate books for me. For my areas of special interest, I want to learn new things, so I’m typically happiest with academic publications or with popular publications that pull off what Barbero does, including a lot of concrete and specific information and letting us in on the journey of discovery as he tells the story.

All the same, sometimes I also love non-fiction books that don’t let us in quite as much as Barbero does; it depends on the book and my relationship to the subject matter.

There are, of course, a few examples in my little home library of history books that really deserve to go onto a shelf of shame, because they’re held together from start to finish by logical fallacies and groundless assertions. This is why I always read more than one person’s work on a subject if it’s going to feature heavily in one of my novels. (For example, the Bayeux Tapestry.) We all get things wrong—goodness knows I sure do—and I won’t throw a book aside just because I think I’ve spotted an error. I might grumble to my long-suffering friends and family if I think its whole thesis is supported by shoddy thinking, though.

I have now gone on about this long enough! Two of my recent reads I can recommend: Straight Acting: The Many Queer Lives of William Shakespeare, by Will Tosh, which is both entertaining and thoughtful, particularly in its discussion of the sonnets. It reframed my relationship to Shakespeare, which takes some doing at this point, 40 years after I read Hamlet for the first time. My current non-fiction read is Shakespeare's Book: The Story Behind the First Folio and the Making of Shakespeare by Chris Laoutaris, which is really deep and interesting so far and has a lot to say about culture in early 17th century England. I’m regretting buying it in paperback, though, as it’s a thick one, and hard to hold open.

You just read issue #27 of Kate Heartfield's Newsletter. You can also browse the full archives of this newsletter.