I’m horrified by the U.S. election and what it means not only for my friends in the U.S. but for the world, and Canada’s politics will be affected too, probably not for the better. There will be more to say; at the moment I am reeling and grieving.

I do believe that the human imagination is key to our ability to fight back, because imagining otherwise is the beginning of liberation—and I believe that as generative and predictive technology threatens to erode original thinking, it is essential for us all to keep our skills sharp. I’m looking forward to this free workshop I’m giving in Ottawa on Tuesday, as one tiny way of using my expertise in that cause. I think we’ve hit the cap of 25 people; if you are on the waitlist, feel free to email me at kateheartfield@gmail.com and I’ll see what I can do; if you’ve registered but find later you can’t make it, please do cancel to make room for someone else. There’s been a lot of interest in it, so I plan to develop an online version of the workshop sometime in early 2025, which will also be free.

Next newsletter, I’ll pass along some of my notes from that workshop.

In the meantime, here are some of the historical images from Paris that I had in mind when I was writing The Tapestry of Time, and which have been coming back to my thoughts unbidden in the last few days.

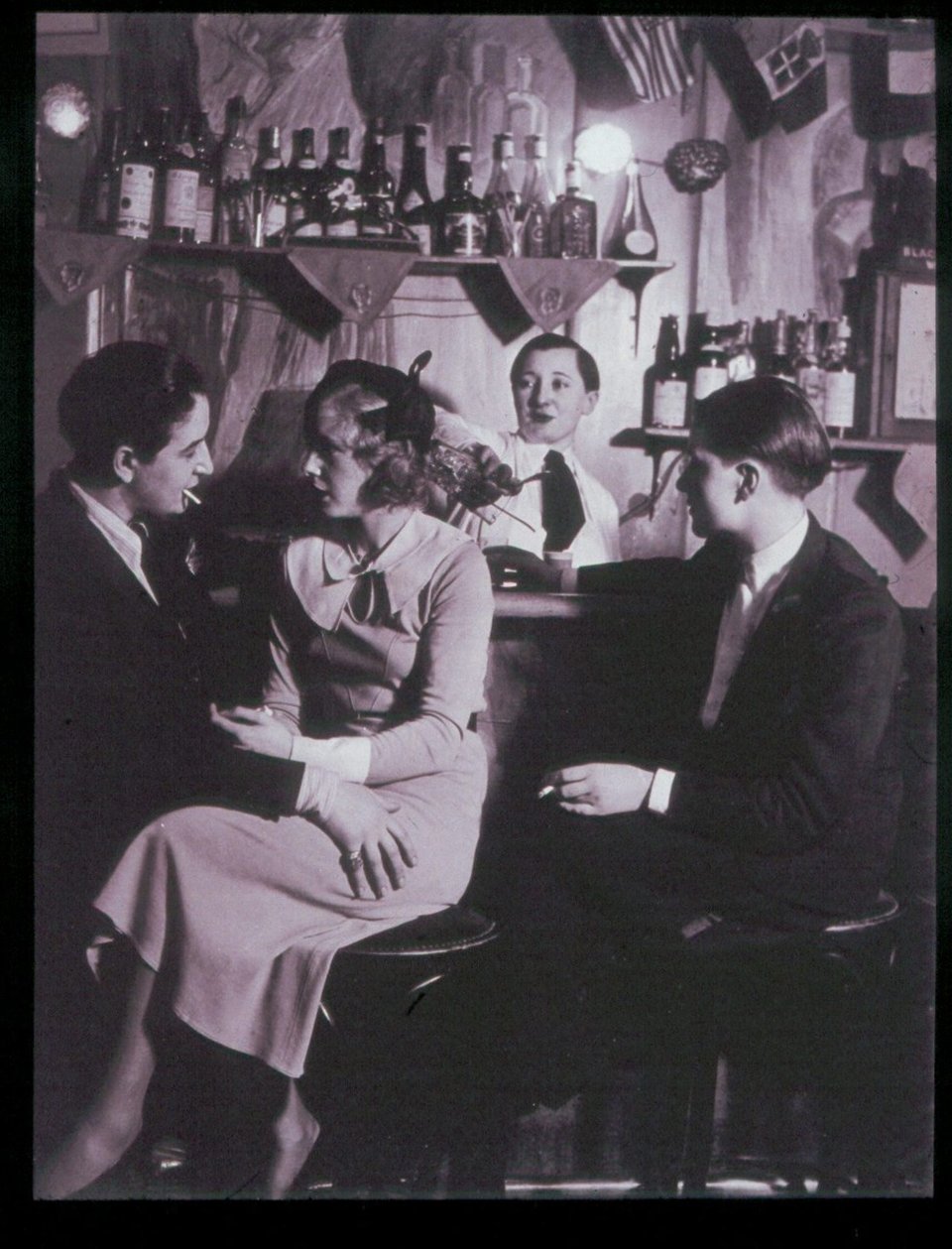

In the novel, there are some mentions of Le Monocle, the lesbian bar that closed down when the Germans occupied France. The purging of homosexuality and transsexuality was of course a central tenet of the Nazi regime and queer people were arrested, imprisoned, sent to concentration campes and sometimes killed, so it was not safe to be openly queer in Paris after 1940. Before that, although of course it was not a perfect and tolerant society, there was a flourishing queer culture.

Here are some photographs taken by Georges Brassaï of Le Monocle in 1932.

The last one is said to show Violette Morris on our right (I have never found a super solid contemporary source for this, but it certainly looks like her and many people assert it, so it probably is.) Violette Morris was a gender nonconforming racecar driver and star athlete in several sports. Partly because of her refusal to conform to notions of correct femininity, her athletic career was blocked in France, but she was welcomed to the 1936 Olympics in Berlin, and during the war, she become a Nazi collaborator, informing on French troop movements, even working with the Gestapo. The Resistance eventually killed her. Her choice to serve evil wasn’t because she was queer — there are many, many more stories of queer people in Paris, including Josephine Baker, who fought against the Nazis, and some even gave their lives in the cause of freedom — but I think of it often as a reminder that fascist hypocrisy is nothing new and they will use anyone they can in their cause, and that turning us is one of their tactics, in addition to imprisoning, torturing and killing us.

I also think of the photographs from Le Monocle in the 1930s as a reminder that progress is not linear, and we can always go back.

The other set of images I have in my mind these days is the group of paintings Pablo Picasso made of a tomato plant in the window of his Paris apartment in August 1944, when the Allies were appropaching and the city was rising up. Something I didn’t realize before researching The Tapestry of Time is that it wasn’t the Allies who liberated Paris, but the people; it was a fait accompli by the time the Allies got there. But the Allied invasion gave the people reason to believe they could get the fascists on the run, that they could liberate their city without suffering retribution from Hitler. People will show extraordinary courage but, in the words of Harvey Milk, you have to give ‘em hope.

The tomato paintings fascinate me because although they do not show the context, the context is key to most people’s experience of the painting; knowing about the bombing happening near the city causes us to interpret the yellowish-grey of the windows in a certain way, for example. In that way, it reminds me of the masterful recent film The Zone of Interest, which illuminates the horrors of the Holocaust by focusing on the uncanny juxtaposition of the domestic life of one of the key architects of the concentration camps; it asks the audience to fill in the context, which is powerful.

You just read issue #23 of Kate Heartfield's Newsletter. You can also browse the full archives of this newsletter.