Hello friends! I’ve been travelling in France, Belgium and the UK for the last couple of weeks. I didn’t plan the trip with this in mind, but our route has been very much the same as the path my grandpa travelled during the “phony war” period in early 1940: over the channel to Cherbourg, then across northern France to Belgium, then to Dunkirk, where he was among those safely brought home (and where we have ferry tickets).

We’ve seen a number of sites associated with D-Day in Normandy, and I was particularly struck by Juno Beach, where the Canadians launched their assault. The Picardy-Belgium part of the trip has been about seeing WWI sites. Nothing about this trip was intended to be book research — it’s for my kid, mainly — but, well, everything is research. I’ve got a future project in mind that involves a Canadian soldier from the Great War, so being on the Somme and in Ypres has been very useful for that. It’s also been wonderful to see parts of the landscape I wrote about in Armed in Her Fashion/The Chatelaine, and imagine Margriet and Beatrix and Claude making their way across those fields and towns.

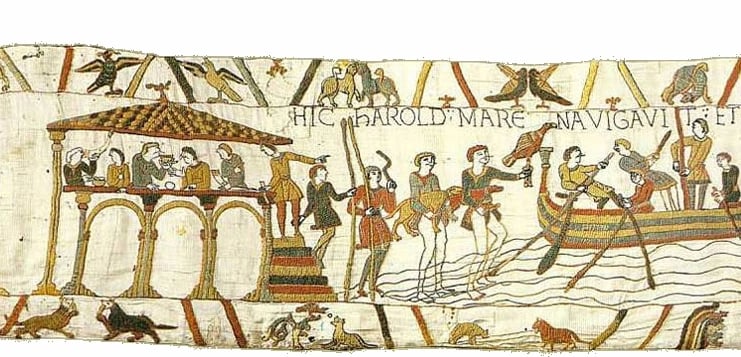

One of the highlights of the trip for me was finally getting to see the Bayeux Tapestry in person. Since the Tapestry plays a major role in my novel The Tapestry of Time, I’ve read a lot about it, and stared at its digitized version for hours, but there’s nothing like seeing the object itself. I’m so glad I was able to. So I thought I’d write this week about that experience.

The tapestry (actually a kind of embroidery) was probably made in the 1070s, and depicts the events leading up to the conquest of England by Duke William of Normandy in 1066. The museum where the tapestry lives now is a very short walk away from the cathedral in Bayeux where the tapestry was (probably) displayed for several centuries. It’s a bare-bones museum, at least at the moment, as it prepares to close for renovation for two years (during which time, the tapestry will make a journey to the British Museum.) There’s a dark corridor with a right angle in the middle, and visitors walk alowly along its length, peering at the tapestry (which is lit well enough to see clearly.)

Like some other museums we’ve seen on this trip, the tapestry museum uses audioguides to supply information about the exhibit. I’m all for audioguides as an option — the more accessibility the better — but I find them tedious when they’re the only way to interact with exhibits. My biggest problem with them is that I just don’t feel present in a space with a device at my ear, surrounded by people who are all also listening to the devices in their ears. It’s isolating and distancing, and it starts to feel like the exhibits are supporting the audio experience rather than the other way around.

(I found it really irritating on HMS Victory in Portsmouth, where nothing’s even labelled, which means the only way to know which cabin or gun or bucket you’re looking at is to listen to the audioguide with all its dramatizations, background context you might already know, and music. It’s the museum version of how when you go searching online for how to fix your dishwasher, you get a 10-minute video you have to watch all the way through to learn this method won’t solve your problem, instead of a quick page of text you can skim for the part that you’re looking for. The Mary Rose museum, next to the Victory, has wonderful text panels and I enjoyed it so much more and learned much more there.)

In the tapestry museum, the audioguides kept everyone moving very slowly, which was nice. They also kept everyone from talking or even whispering, which had pros and cons. The silence did help to support the sense of awe, of the experience being sacred in some way. (Somewhat undermined by the person coughing, blowing their nose and snuffling right behind me. It’s a small, somewhat crowded corridor, definitely worth masking up in.) But it also meant that, as I never felt comfortable speaking, I didn’t point anything out to my partner and kid, with the result that when we stopped for ice cream later and I mentioned the nude figures in the margin, my partner looked confused. “Nude figures in the margin?” I absolutely would have pointed that out, if I’d felt it was OK to speak, and if I didn’t assume that the audioguide would mention it. And I would have pointed out a lot of other things the audioguide apparently did not.

The most interesting panel, if you ask me.

It’s interesting to think about how the museum experience is changing as audioguides become more popular. They tend to make these experiences somewhat passive and individual, rather than collective — no talking, no sharing of anything but germs — which maybe is more spiritual in some sense, and definitely less distracting than kids loudly pointing out the funny parts — but isn’t there something joyful about kids pointing out the funny parts, too? I miss the personality of human tour guides, while I’m complaining.

So as you’ve probably gathered by now, I didn’t use an audioguide myself, because I wanted to feel present and experience the object on its own terms, and because I gambled (rightly, as it turned out once I compared notes with my partner) that the audioguide would have a pretty basic level of information which wouldn’t add much for a Tapestry nerd like me.

The first thing that struck me about the object was the texture of the stitching, the way you want to reach out and run your fingers over it. (It’s covered in glass, luckily.)

Even though I was familiar with each scene already, seeing it full-sized and close up really made me appreciate the life in all its details — the expressiveness of the figures, the humour and energy and creativity. I was struck by the bare legs of the men standing in the waves with their clothing tucked up, for example — somehow that image felt more dynamic and human, seeing it in the actual embroidery.

It’s also incredibly beautiful. I appreciated the weird stylized trees, with their knotted branches, and the stately, energetic horses so much more in person.

That closer view of the stitching also made me see some of its details in a new light. The biggest example of this is the famous panel ostensibly showing King Harold taking an arrow in the eye. I already knew that the arrow was added in a 19th century restoration, and that the figure in question probably isn’t even Harold. In person at full size, my reaction was: holy crow, that arrow is unconvincing. It is so obviously squished in at a weird angle.

I’d love to see the renovated museum devote some space to letting visitors know about the mysteries and weirdnesses of the tapestry, such as the long debates about who commissioned it and why, the impact of the restorations, the questions about its content such as the identities of Aelfgyva and Turold, the questions and theories about what it’s saying about Harold’s death, and the storied history of the tapestry as an object, a lot of which is built of educated guesses. For me, it’s everything we don’t know about the tapestry that makes it so fascinating.

In any event, it’s an enormous privilege to have seen this unique object, in the equally beautiful city of Bayeux.

You just read issue #43 of Kate Heartfield's Newsletter. You can also browse the full archives of this newsletter.