Hi everyone! I am now writing from Stockholm, Sweden. I just began another postdoc research position in the Department of Physical Geography at Stockholms Universitet. I'm working on a project here about wetlandscapes–a neologism that deserves another post sometime soon, but I'll write that once I get some clarity on what I want to do in the job. For now, I'm getting to know my new city.

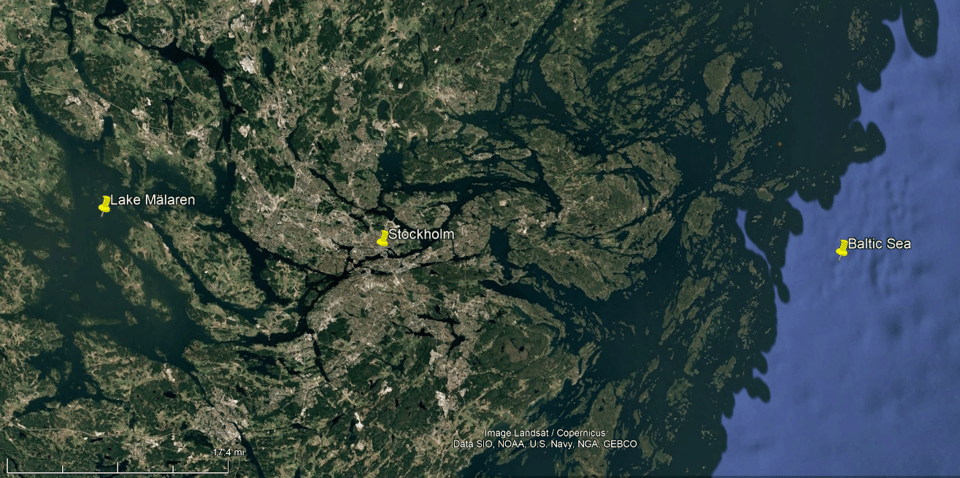

Stockholm doesn't have much for surfing, which makes me terribly sad, but it is perhaps even more of an amphibious urban area than the Bay Area. As you can see from the satellite image above, Stockholm sits within a very watery landscape. To the east is the vast array of islands called the Stockholm Archipelago within the Baltic Sea. To the west is an interconnected landscape of lakes, river channels, and wetlands, dominated by the enormous area of the lake Mälaren, which supplies drinking water to Stockholm.

Figure from Wikimedia.

Figure from Wikimedia.

Stockholm is strategically located at where these lake and sea systems meet. The arm of the Baltic Sea here is called Saltsjön, or "Salt Lake," because it is just a little bit salty. The region has been settled long enough, and is undergoing post-glacial rebound quickly enough, that it has endured dramatic water level changes over its human history. In other words: since the glaciers have receded from this place, relieving tons of weight upon the region, the land has been buoyantly rising out of the earth's mantle at a centimeter or two per year, lifting the city by meters over centuries. Because of this, the western, freshwater lake portion of the city only became a separate lake in the 12th or 13th century, as it lifted above the Baltic Sea! (See this reference by Lars-Erik Åse, 1980.) This has made some of the waterways going east-west through Stockholm crucial stopover points in travel, due to rapids flow and locks, which I'm sure has fueled Stockholm's growth. I'm curious what this transition used to be like, in terms of saltwater exchange: the Baltic sea in general is not very salty, as the whole sea is essentially an enormous estuary from rivers of the Fennoscandian peninsula (see this figure), but I wonder how salty Mälaren used to get. Some research suggests water has gone upstream from the Baltic into the lake as recently as the 1970s (ref).

Image from the Åse 1980 paper linked above.

Image from the Åse 1980 paper linked above.

The figure above is a bit hard to read, but I like its charm. Through Stockholm, between Mälaren (the western lake) and Saltsjön (the eastern bay), there are four connecting channels from north to south: 1. Norrström (lit. "north stream," which people seem to call a river), 2. Stallkanalen immediately south of that, separated by a tiny island, 3. the slussen ("lock", formally Karl Johanslussen and formerly Söderström, or "south stream"), and 4. Hammarbyleden/Hammarbyslussen. This last one was made in 1929, taking large boat traffic south of Södermalm, rendering the landmass an island. Given that the southern three are a canal and two locks, almost all of the water flow into the Baltic comes through the northernmost, Norrström (ref).

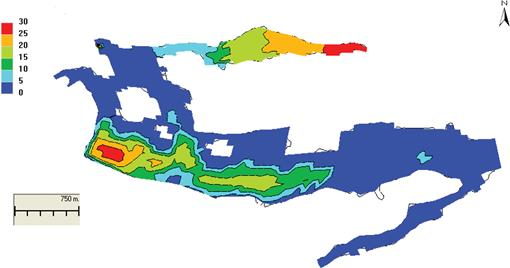

Residence time of waters in Saltsjön, in days, from Dargahi & Cvetkovic 2011 (ref).

I'm interested in all this because I just like hydrodynamics, and I'm hoping to swim and paddleboard in these waters before the winter cold truly sets in, keeping my shoulders in shape before my next surf session. More importantly, though, the flows between the lake and the sea implicate water quality of the brackish Saltsjön bay (e.g. how well-flushed is it or are pollutants compiling?) and saltwater intrusion into Mälaren, which is a risk under our changing climate.

Stockholm as a city is rich with swimming, kayaking, paddling, sailing, fishing, and sauna-ing, which can all help build a culture of attachment and care for its bodies of water. I'm excited to get to know these hydrodynamics and cultural relationships better as I get to know the city and what makes it flow.

Between lake & sea,

Lukas

p.s. As you might guess, the move to Sweden is an opportunity for a lot of life refactoring. I'm aiming to ramp up my writing here, sharing more of my work and the landscape of ideas that fuel my love for environmental issues, and making a paid subscriber option (!?) to support the work. Stay tuned!!

You just read issue #94 of Gnamma. You can also browse the full archives of this newsletter.