We're in peak surf season here in San Francisco, and thus far we've had a terrific run of surf. I've been paddling out as often as I can, and my favorite place to do so is Ocean Beach, San Francisco (OBSF). This enormous, windswept beach comprises almost the entirety of the western edge of San Francisco, running almost due north-south.

OBSF is really an amalgamation of a number of different waves and constantly-shifting sandbars. The surfers typically refer to them by cross-street, which are mostly alphabetical (Anza, Balboa, Cabrillo, ... Irving, Judah, Kirkham, etc). My favorite place to surf is the south end of the beach, typically around Ulloa, Vicente, Wawona, and (non-alphabetical) Sloat. Currents at the beach can be intense, so as a surfer you are constantly looking for landmarks that can notch how far you've been carried. At Vicente is a large storm drain, and by tracking this, I can take stock of how fast I'm drifting. (There is a second one at Lincoln, further north on the beach.)

Image from SFGate.

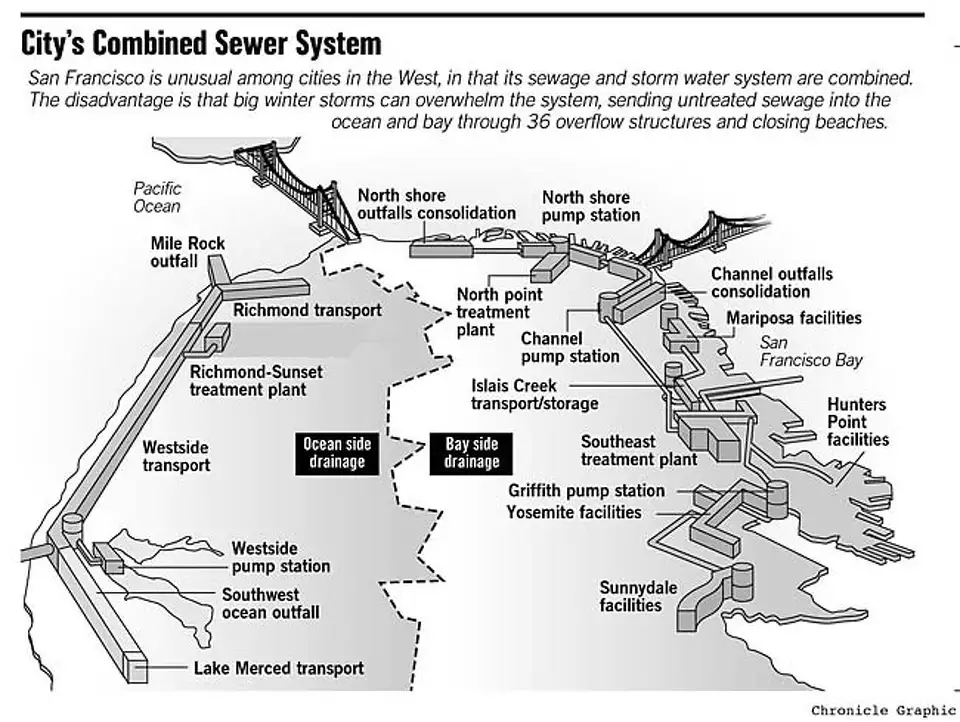

These storm drains are overflow pipes for San Francisco's manmade water drainage system. San Francisco is essentially the only major Pacific Ocean-adjacent city with a "combined sewer" system, meaning that the pipes that drain rainwater and the pipes that drain sewage are shared. (Seattle also has this, draining to Puget Sound.) Because sewage is combined with stormwater, when it rains in San Francisco, there is enormous stress on the capacity for the city to process all of the water through its three treatment plants. Two are to the east—on the side of the bay—and one is on the ocean, just south of Sloat Boulevard, approximately near the Westside pump station in the below cartoon:

Image from SFGate.

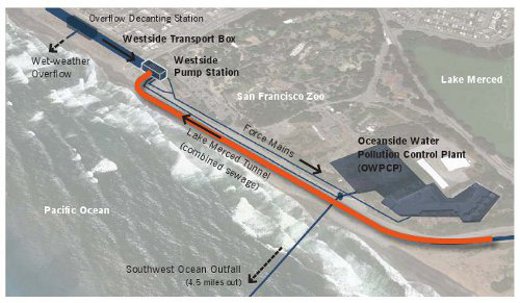

To avoid the environmental disaster of leaking a stormwater-sewage mixture straight into the ocean or bay, the city has built large storage tanks, which can fill up during periods of high flow, to store water to be treated later. At the Oceanside plant, this overflow fills the "Lake Merced Tunnel." In this tunnel, overflow gets at least decanted (a primitive primary sewage treatment) before discharged out the deep-water outfall pipe. Only in really extreme flows (according to SPUR) does this system get overwhelmed, and stormwater-sewage discharge does exit to the environment via storm drains, like the one at Vicente. Don't go for a swim after a big rain dump!

Image also from SPUR.

Wastewater treatment plants are virtually always placed at low elevations. It reduces costs: water flows to them, reducing the need to pump sewage into the plant. It just flows there naturally. For this reason, wastewater treatment plants are an interesting case of critical infrastructure facing the reality of sea level rise: in coastal environments, they are right at the front lines, and high sea levels can cause major backups and failure in their engineering. The Oceanside water plant is a prime example of this, nestled in a small valley right by the ocean, so that all the water from western San Francisco flows downhill to it. The building itself isn't immediately threatened —it's up on a bluff maybe 20 ft above sea level—but the Lake Merced Tunnel is buried at a low elevation, right next to one of the most dynamic beaches in California.

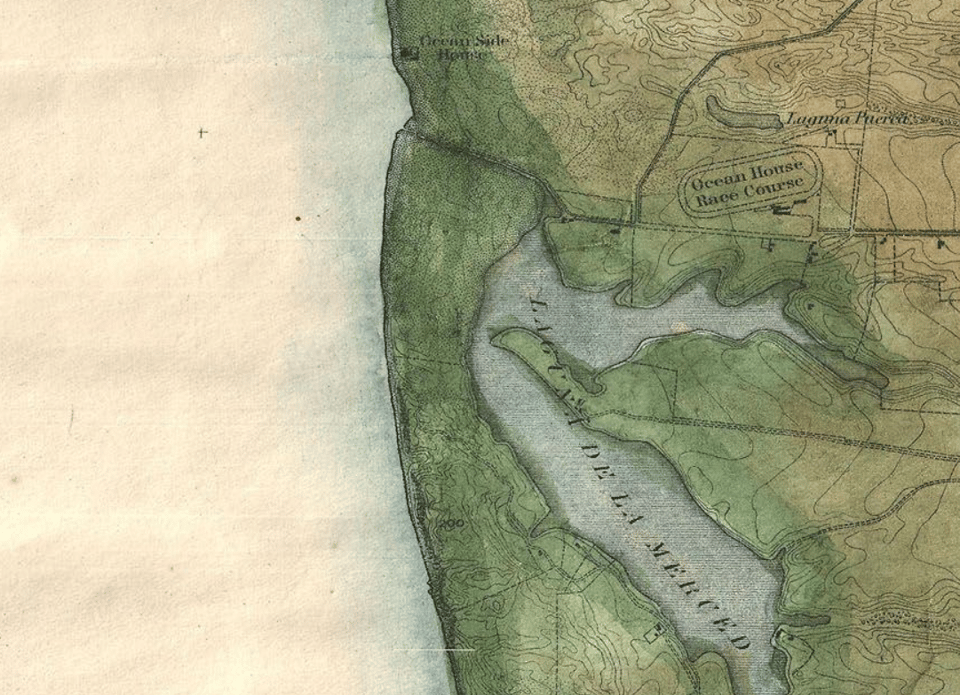

Adding to this complex of factors is the proximity of Lake Merced itself, the tunnel's namesake. Lake Merced is a freshwater lake that has historically flowed out to OBSF via a channel that—as far as I can tell from historical maps and imagery—was just about at Sloat Boulevard. Historical accounts suggest that in the mid-1800s, after a period of lake-ocean connectivity via a major breach in the sand dunes, the connection was filled-in by migrating dunes, dammed, and is now built-over. (Hat tip to my friend Arye, who first brought this to my attention.)

Dynamic little creeks that connect lakes, lagoons, and estuaries to the ocean are ubiquitous along the California coastline. Their mouths constantly move around and often plug, due to waves stuffing them full of sand, only to be re-opened when the rare rainy event brings enough flow to plow the mouth open again. (Or bulldozed, when managers decide it's important, as in the Russian River and some San Diego County lagoons and elsewhere.) So it's no surprise that there was a little intermittent creek mouth here at Lake Merced and Sloat Boulevard, but it speaks to the dynamism of this specific location where the wastewater plant, the coastal highway, and an enormous beach all meet.

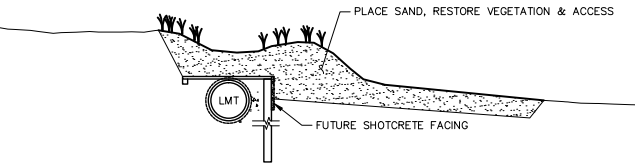

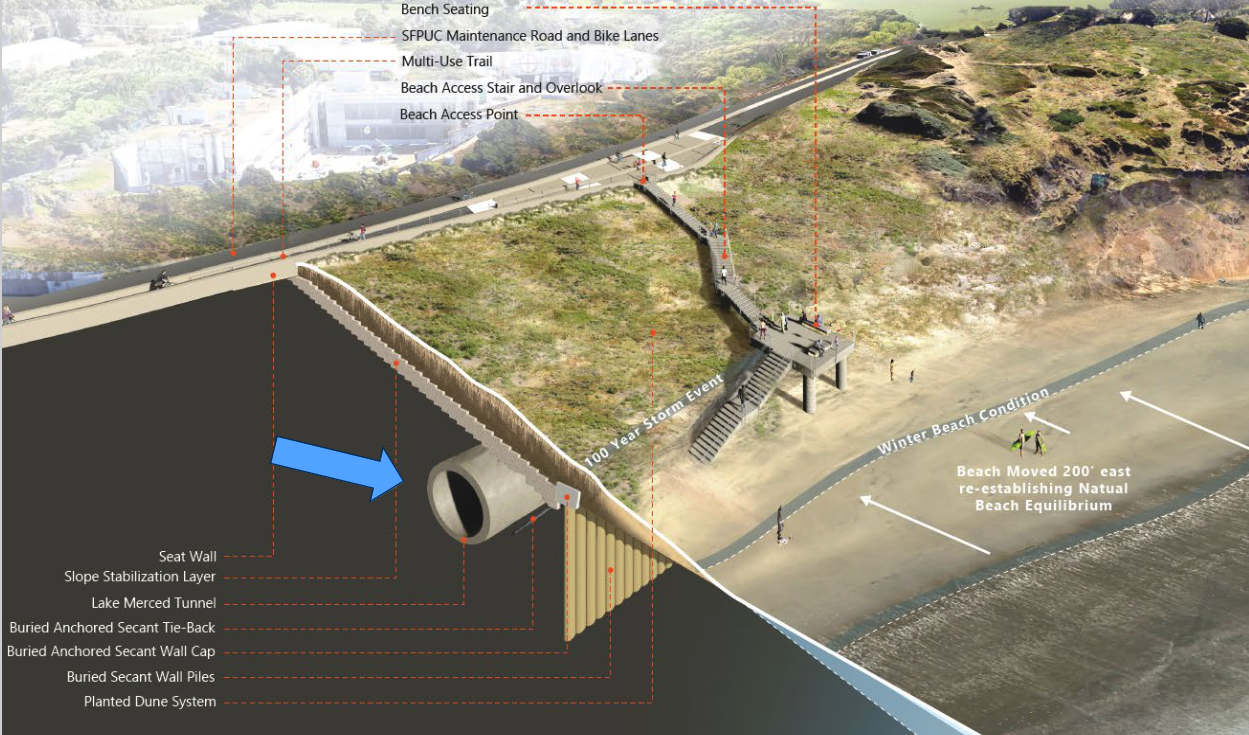

This south end of Ocean Beach has been eroding—meaning long-term loss of sand volume—for years. Exactly why is a whole other story, related to available sediment and the ebb-tide delta of the Golden Gate... it's also good to mention that most beaches have very different summer versus winter shapes, so the same volume of sand can move around seasonally before it is ultimately "lost" by moving further offshore. Regardless, coupled erosion and sea level rise make the infrastructure around Sloat quite vulnerable in the next couple decades, and this eroding region has been the nexus of some planning initiatives like the 2010 Ocean Beach Master Plan, and a 2015 coastal engineering plan for the south end specifically. And now, just recently in November, the California Coastal Commission granted approval to implement some large-scale changes in this area, the grandest of which are the removal of some facilities and roadways to effectively retreat from this erosion hotspot, but also to build a subterranean wall to protect the Merced Tunnel.

From 2015 OB Coastal Protection Plan.

This plan has been the cause of much consternation, and "seawall can be a dirty word" says a friend of mine. Various organizations (including surfer stuff like the Surfrider Foundation) have raised concern over the seawall, pointing to engineering studies that have spoken to how seawalls can exacerbate sand loss and erosion around them. So while a seawall can protect one specific thing, it can cause larger impact in its vicinity and neighborhoods. I believe this to be true, particularly in the "cross-shore" direction (i.e. perpendicular to the shoreline, like in the transect graphic above), where sand can be scoured away in front of the seawall. Beaches however are rivers of sand, so there is a crucial "longshore" component (i.e. along the beach) too, where a seawall's effects may be somewhat more ambiguous. I think that sand just moves through a seawalled portion faster than elsewhere on its trip through the beach.

While I want to give a nod of appreciation to those raising concern, I think the proposed measures of protection for the Lake Merced Tunnel are actually very well-considered. It's buried, thus unlikely to ever be visible unless there is a dramatically erosive year, and connected to a large-scale beach system with low risk of truly starving the entire area of sand. Will the sandbars right next to it be affected? Maybe! As I return to often in this newsletter, the crucial thing is timeline of expectations. San Francisco could continue to do very little intervening for the sewer system here, increasing risk of catastrophic failure and sewage overflow of the sort that would be very difficult and expensive to patch. It could begin to spend on the order of billions to relocate some of this sewage infrastructure a bit further inland, maybe closer to Lake Merced. Long-term, this actually does need to happen. But the city can buy itself decades of time—and protection from ecological disaster—by spending millions now to make this intervention at Sloat. In an age of staggering delay to future infrastructure needs, I think this is actually fairly pro-active. We cannot build new wastewater treatment infrastructure any faster or cheaper than we can protect it, and the ecological value of keeping it working is very high.

From this great long read about more of the science and management of these issues in SF and Santa Cruz.

Zooming out, the plan is about as much managed coastal retreat as is immediately possible for the region. Removing the sandy-and-urine-caked bathroom at Sloat (I say this lovingly, I swear), the parking lot that's crumbling into the sea, and a dangly little connector road gives the bluff-dune landform (eco)system much more space to buffer itself against coming changes. Slow retreat from this region has been in the cards since the 2010 Ocean Beach Master Plan and it's finally getting real.

Image from here.

The most exciting thing is that this is moving at the same time as city proposition K passed, initiating the process to close Great Highway indefinitely, the major road that runs immediately inland of the beach. This stretch of road is completely redundant with other nearby arteries, and costs the city loads of money each year to bulldoze sand to keep the southbound lanes open as the dune field tries to reclaim its old territory. It's not yet clear at all what this new region—ostensibly a new city park—will look like exactly, but in combination, these things speak enormously to San Francisco's willingness to do some coastal retreat and give OBSF a bit more room to breathe.

There are enormous potentials for habitat restoration across all of Ocean Beach to its southern reaches, rebuilding some of the dunefield that formerly covered about half of the city. I'm excited to be one of the last generation to play frogger between the cars on Great Highway to go out for a surf, and I'm so excited to see how the region will change going into the future.

Keep your dog on-leash,

Lukas

You just read issue #90 of Gnamma. You can also browse the full archives of this newsletter.