I was in Los Angeles last week (one of the upsides of working remotely in my postdoc thus far!), so Elena and I snuck in a visit to one of my all-time favorite little institutions, the Center for Land Use Interpretation. The Center was immediately on my radar when I moved to Los Angeles in Fall 2018, I think via a recommendation by a friend-of-a-friend who loved its quirky nature and its both real and performative institutionality. This manifests as an layer of bureaucratic aesthetics over what is really a passionate and artistic dive into critical geographic and (landscape) architectural theory.

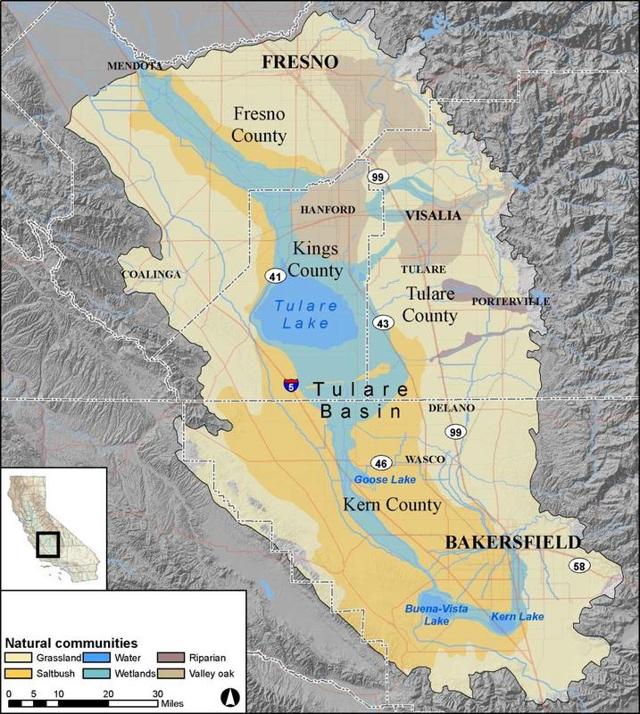

The show on display at CLUI right now is Tulare, a series of photos, videos, maps, and words on Lake Tulare. To say whether Lake Tulare "exists" or not today depends on what exactly you're waiting for, but the lake loudly announced its re-arrival in the extremely-wet 2023 at the southern end of California's Central Valley, causing widespread flooding. The lake has since retreated, divvied up into evaporation, groundwater percolation, and surface water diversions (i.e. canals and streams). These diversions are part of how the region has now been lasso'd into agricultural use across in the former freshwater lake and wetlands. Intermittent lakes and rivers, with these large seasonal or multi-year swings in their hydrologies, are somewhat common in arid landscapes around the world. Tulare is just particularly huge (> 1000 square km) and intertwined with California water infrastructure and politics. The fertile and, most-of-the-time dried out lakebed is now the terranean jewel of the J.G. Boswell Company, the "biggest farmer in America" (thx Elena!), whose lobbying has had outsize impact on dam and levee and canal construction in the region. Ultimately, this same construction now mostly prevents Lake Tulare from swelling during wet seasons as it has done for millennia.

The dogged persistence of bodies of water is one of their attributes I most admire. Despite all the bulldozers in the world, it's just pretty tough to move enough dirt and rocks to meaningfully change how the earth's landscape is shaped, and water still flows and collects downhill. A lake drained out of existence by pumps and dikes exists as the potential to re-emerge, with enough melting snow pointed towards a shallow bowl-shaped geography, as happened last spring in Tulare. All of the earth's surface is always changing, but rivers, lakes, and wetlands (both freshwater and salty) are particularly dynamic; while water is inherently geographical, it is less fixed-in-place than many other physical landscape entities; plus its heft, cyclicality, and slipperiness make it difficult to engineer around. These dynamics challenge imposed management regimes or expectations for our environments to behave to our desires in many ways, some of which I've written about previously in this newsletter. Particularly, the ebbs-and-flows and murky edges of wetlands–including the tule reed landscapes of Tulare–contribute to their particular positioning as difficult landscapes, of sorts, to manage.

Caterina Scaramelli writes about the myriad socio-technical dynamics embedded in Turkish wetlands, but I think the words could be relevant in many hydrogeomorphic (land-water) systems:

[Wetlands are] shaped by and, in turn, shape other kinds of interconnected infrastructures. Wetland ecologies exist, thrive, and die shaped by the processes animating infrastructures as varied as irrigation canals, roads, commercial forests, power plants, factories, fishing lagoons, and bridges. Wetlands' seeping quality, the ambiguity of their boundaries, and their seasonal rhythms make them evocative and important places to stake political claims about the materiality of [their social] ecologies.

A hemisphere away from Turkey, Tulare Lake represents the ongoing saga of a political and economic stake (i.e. California "big Ag") within a "phantom" hydrologic regime; a farm against the floods. There is a necessary ontological leap to pursue this logic: that the climatic and terrestrial conditions of the place are prior to, or more fundamental than, the human-driven activities happening in a place. This is, especially in places with millennial-scale histories of wetland modification (e.g. Turkey) or among some of the biggest water infrastructure projects on earth (e.g. California), not entirely true. Scaramelli's note on entanglement is a reminder that, well, J.G. Bosworth's farm land was both "in the way" of the flood, but also exactly where the lake used to flood because it was fertile, and the nature of the flooding is intertwined with how California, at a state level, stores and directs its snowmelt across the state via reservoirs and canals. Giving primacy to the hydrologic processes of a place is a classic engineer's fallacy. Hammer, see nail. (I am battling this tendency to focus on water-driven patterns in a paper I'm writing about marsh-top sediment deposition, and Scaramelli describes it as a default technocratic stance amongst many wetland scientists and managers in the book referenced, too.)

The water is not the sole agent in this tension of Tulare Lake, but its persistence–more than its lack of absolute permanence–means it absolutely cannot be ignored. More dramatic hydrologic swings are already happening thanks to accelerated climate change. It will be exciting to see what other systems as dynamic as Tulare are out there, what new ones will emerge, and how they all dance together with their intertwined histories of settlement, stewardship, extraction, instrumentalization, and management.

Interpreting the land use,

Lukas

You just read issue #88 of Gnamma. You can also browse the full archives of this newsletter.