I wrote in autumn about my PhD dissertation work in Gnamma #95 - How A Marsh Falls Apart. My research was mostly a close examination of a single marsh in South San Francisco Bay—Whale's Tail Marsh South—and the physical forces affecting its shape (geomorphology) and evolution. One part of my dissertation work has continued to puzzled me, though, a lingering question about the fate and history of the place. Here I will share why, and my best running hypotheses as to what is going on.

Before I jump into it though, I have a plea. Now that my PhD work is all published, I am sharing it at the AGU Ocean Sciences Meeting in Glasgow, Scotland later this month! But, due to the weirdness of academic funding timelines, and because I'm showing "old" work, I couldn't get much any financial support to attend this conference. It's crucial that I get my ideas out there and network with people at conferences like this, so I'm self-funding myself to go, but to a cost of about $1000. If you are a fan of my work or want to help support this last dribbly bit of my PhD, please consider giving $10 to offset these costs!!! I have set up a GoFundMe here (link fixed!). For those of you who already support this newsletter financially, I am putting your support from December, January, and February towards this cause, no need for any more! Thanks a billion. Now back to the science.

Google Earth screengrab of the marsh in question.

Google Earth screengrab of the marsh in question.

Whale's Tail Marsh South, hereafter "WTMS," is a small marsh with levees on its north and east sides. It doesn't really have a south side, due to its wedge-like shape and the outlet of a tidal creek. The western edge faces the water of San Francisco Bay, and this geography is critical because the marsh is hemmed-in. The levees prevent the marsh vegetation from growing in any direction except out towards the water. Unfortunately, the nearby waters of San Francisco Bay has some of the biggest waves in the region, because the dominant wind direction goes directly across the widest part of the Bay here: the when winds blow across long distances of open water—called "fetch"—bigger waves can be made. In my research, I linked these waves to rapid erosion of the edge of the marsh. So this marsh's one unconstrained boundary is actually retreating, moving landward at a median pace of 1.5 meters per year from its western edge (see my paper!). Be aware, the marsh itself is only about 300-500 meters wide. With these facts together, this marsh is on a short timeline to self-destruction, as I also wrote about in Gnamma #79.

Figure from my paper showing retreat rate of the marsh-edge scarp over a year.

Figure from my paper showing retreat rate of the marsh-edge scarp over a year.

Landforms can be essentially stagnant in shape, which we may call being in steady-state or equilibrium, if they can "build themselves" as fast as forces of erosion cause them to degrade. Or the landforms can be non-equilibrium, where we see the landscape in the middle of a process of being produced or destroyed. Things can also be pseudo-equilibrium or quasi-equilibrium, or various other terms if you want to get into some nuance—there is always the question of "stable on what timescale?" Because the morphology of the landscape often affects how things act on it, geomorphologists are also constantly dealing with chicken-and-egg, causal-loop problems. If water flowing through a valley is dependent on how the valley is shaped, and the valley is also sculpted by the flow of water itself, how do we understand the shape and the process together, feedbacks within a system? (Good computer models have helped with this somewhat.)

Photo of WTMS by my former boss, Jessie Lacy

Photo of WTMS by my former boss, Jessie Lacy

Our marsh of interest, WTMS, is clearly not in equilibrium. It is rapidly eroding, and there is no way for it to prograde or expand given the intensity of the waves driving erosion in San Francisco Bay (and perhaps limited sediment supply). So, how long has it been eroding? What did it look like when it was in the process of being formed? What changed, forcing this marsh into its erosional regime?

My first guess is that, because we're currently in a period of rapid sea level rise, the marsh is responding to that. Coastal salt marshes exist right about at sea level, so on geologic (or at least interglacial) timescales, they move down in elevation when sea levels decreases, and move up in elevation when sea levels rise. Sediments from salt marshes are even used to recreate Holocene tide levels (Barlow et al. 2013)! But we need to keep in mind that 10,000 years ago San Francisco Bay didn't even exist—rising sea levels first needed to fill it in. Did the marsh first emerge as saltwater crept into the Santa Clara valley? Then, when did it start eroding?

There is a channel on the west side of South San Francisco Bay, which is likely where rivers once flowed, going north towards the Golden Gate. This channel is roughly 4000 meters from the current edge of Whale's Tail Marsh, and the distance is now all mudflats, some of which get exposed at low tides. It seems like estimates of when the water level in the Bay stabilized put it at about 7000 years ago. (Note, until the 1800s, sea levels were pretty stable for thousands of years; now they are changing rapidly due to anthropogenic climate change.) It's likely the marsh retreat rate was much smaller than our measured 1.5 m/year previously, as the bay would have been less wide and thus waves smaller. (Note, the winds making the waves have likely changed less rapidly than these other aspects, so I'm not treating wind strength with much attention.) All of these factors combined, it's reasonable to think that perhaps 4000 meters of marsh was eroded in about 7000 years.

So one theory is that when sea levels stabilized, most of South San Francisco Bay was more "filled-in," colonized at its margins by salt marsh, likely with some grasslands just upland. And this salt marsh margin, and even the mudflats, began eroding—probably slowly at first and now rapidly—widening the bay up to where it is today.

I think that these factors do explain a lot of what's going on. But these a few thousand years would be quite a long for sustained marsh retreat; from what I understand, most marshes move back-and-forth in the shoreline depending on other factors like storms and cycles like El Niño. I've been curious for other, shorter-timescale mechanisms that would explain the rapidly-changing disequilibrium landscape I encountered at WTMS. Was there some shock to the system that pushed the marsh into an erosional regime?

My own photo from 2021 of a ground control point for aerial imagery, pinned into a "beach" of shell material at WTMS (2021).

My own photo from 2021 of a ground control point for aerial imagery, pinned into a "beach" of shell material at WTMS (2021).

When our team was spending time out on the marsh, we kept finding bits and pieces of oyster shells. There was even a small beach of oyster remnants ("hash") at the south end of WTMS. Yet, there were no oysters or oyster beds to be seen. We speculated on where it all came from as fodder for good banter during field work. But it wasn't really our research goal to figure it out, and we never dug into it. I have kept thinking about it, though.

In early 2025 I began some volunteer work with Wild Oyster Project, a nonprofit seeking to help bring back native Olympia Oysters to San Francisco Bay. The organization is modeled after New York City's Billion Oyster Project. I obviously had some ambient knowledge of oysters in the area, but I had no idea just how widespread they had been in these brackish waters nor that their population has been decimated, to less than 10% (maybe 1%!) of what existed prior to the population boom of the 1850s.

Not only were edible oysters harvested to virtual extinction for food, but their shells—the natural beds as well as the detrital middens from generations of oyster consumption by Native Americans—were extracted away to be pulverized and used as a natural source of lime for mortar in construction. Oysters depend on shells of their kin to grow, especially in muddy substrate, so this eradication was near-total, and happened simultaneous with rapid silting-in of San Francisco Bay due to mining activity following the 1849 Gold Rush.

A story has started to emerge in my mind: were there formerly oyster beds offshore of WTMS? Oyster bed/reef complexes are considered to help protect marsh edges from erosion, by wave blocking or attenuation. Were we finding remnant shell material at the field site from a long-gone oyster population which protected the shoreline?

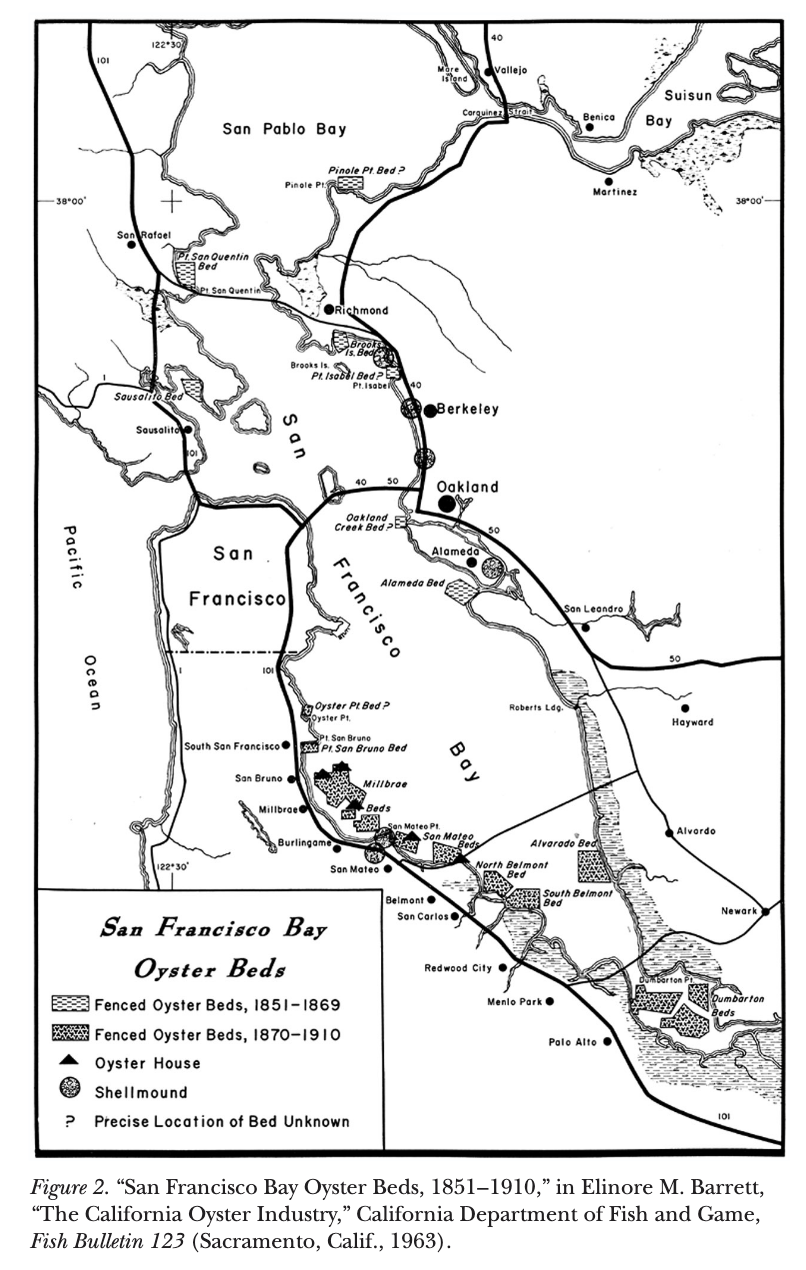

Information about historic locations of oysters in San Francisco Bay is a bit sparse. I doubt the oyster harvesters in the late 1800s were concerned with producing data as much as they wanted to capitalize on the rush of people and food and making money. A 1963 Fish Bulletin by Elinore M. Barrett suggests that right at the site of WTMS was a commercial oyster bed, 1870-1910 (Reproduced in Oyster Growers and Oyster Pirates in San Francisco Bay, 2006, by Booker). See the image below, called the "Alvarado Bed."

I can't find anything predating this. The history of the ancient shellmounds of San Francisco Bay is somewhat piecemeal, and this report, "Shellmounds of the San Francisco Bay Region" by Nelson in 1909 does not suggest there were any shellmounds nearby (see image below, the nearest are by Coyote Hills), discouraging an idea of a rich oyster population there. Or maybe the edge was just less explored than others.

Snippet of the map in Nelson's 1909 report.

Snippet of the map in Nelson's 1909 report.

In sum, there definitely was a sizeable oyster population at WTMS at the turn of the 20th century, maybe due to aquaculture, which later crashed. I don't have enough information to put more of the story together, yet. But my intuition right now is that the loss of oysters and oyster beds in this region of San Francisco Bay, likely 100-150 years ago, helped plunge this shortline into rapid erosion. Maybe it was the combined massive shock to the system of extreme sediment swings and loss of oyster beds. It's possible the major changes came a bit later in the 20th century, when the sediment load turned into a sediment shortage and any remaining oyster reefs were totally buried or deeply degraded. A hundred years of rapid edge retreat are easier to believe than 4000, and likely the marsh edge did not extend all the way to the channel. I would guess that the marsh transition to mudflat at its edge was more gently sloped, or populated by eelgrass, or directly abutted oyster reefs—anything other than its eroding cliff-like edge today.

Research on how marsh-oyster complexes evolve over time is not very robust, and historical ecology perspectives on them are rare. If I had some money to do some deeper document analysis, take some sediment cores out in the nearby mudflats, and do some dating or provenance fingerprinting on the shell hash at WTMS, I believe we could start putting together a story—one that would be relevant across a lot of San Francisco Bay. Ostrea lurida and the marshes were dancing together for thousands of years; I think it's believable that their separation is the main reason for the rapid marsh loss here. Maybe this mission to restore the oysters will help all of these processes return to a state of balance as well. As we so often find in earth sciences, all of the processes are intertwined, somehow.

Shucking,

Lukas

P.S. For those readers invested in my (non-synthetic) gusseted pants quest, my recently-acquired Blue Lug Pants are a winner. 100% cotton, very affordable, fun details, and a wonderful small brand to support. Other than that, the Gramicci Pants are stellar if you like organic cotton and their particular details at a slightly higher price point. And if you've got that baller lifestyle, almost all of HAVEN's pants have great gussets, and some of them are made with natural fabrics. Happy riding.

You just read issue #102 of Gnamma. You can also browse the full archives of this newsletter.