The scientific research project that is currently employing me is called "Disclosing Overlooked Wetlandscape Ecosystem Services" (or DOWES—see more info here).

This jargon-laden title is a mouthful, but underlying it are some questions that are not so complicated:

- when do wetlands depend on the broader landscapes around them to work and be healthy?

- what things do wetland(-scapes) do that we have previously overlooked or under-quantified?

The first question is the one that explains the neologism “wetlandscapes.” This term correctly evokes “wet landscapes” and “wetland scapes.” The DOWES team is currently writing a manuscript to extend existing definitions of this term, given lots of potential confusion.

At a very simple level, a wetlandscape might be identical to a watershed. (That is, the region where, if rain fell on it, the water would flow downhill to a common point.) One typically says "the watershed of X," where X is a stream, or a lake, or some feature—then from that feature we look uphill to find the watershed. This definition unites a region by its hydrology and geography: even though a "wetland" might only be a small portion of the area, the function of the wetland, which is driven by hydrology, depends on flows through the watershed.

from the South East Alberta Watershed Alliance

from the South East Alberta Watershed Alliance

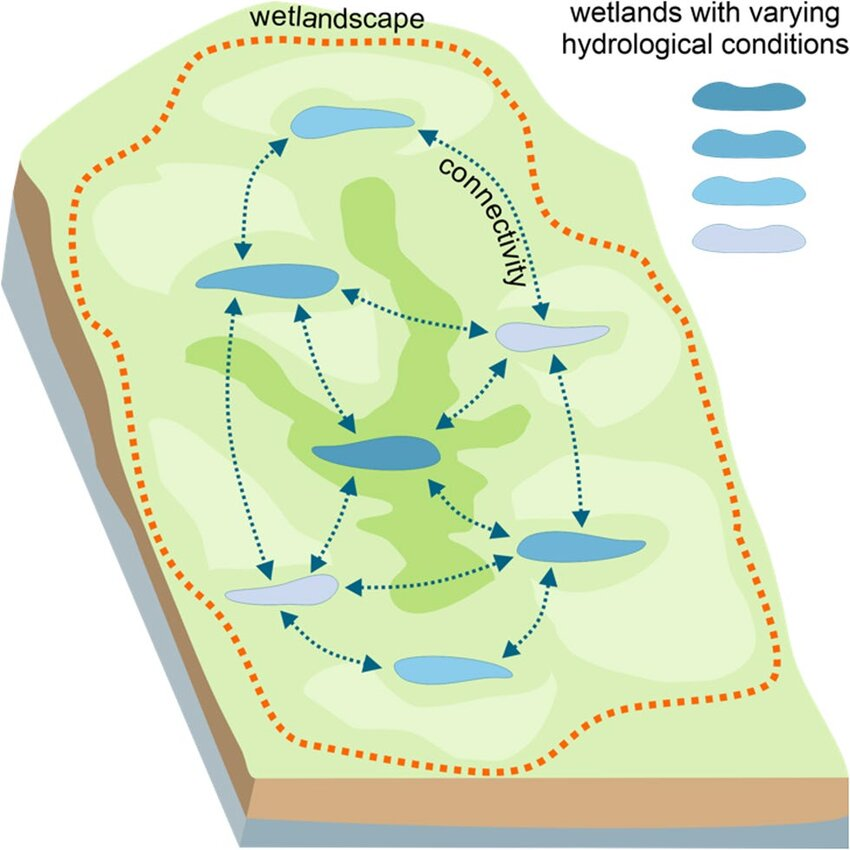

But sometimes a watershed is too big of a scale, and not focused enough on the wetlands. Another common definition of "wetlandscape" is reflected in this figure by Ma et al. (2025):

Basically, that a wetlandscape denotes a landscape or region that includes interconnected wetlands. I like this definition and tend to think this way by default: the blue dotted lines of "connectivity" would simply be surface water flows like rivers and streams. In a place like San Francisco Bay, one could conceptualize that the wetlands are not connected by rivers but by a bay that every wetland touches.

Some wetlands are not connected by these obvious bodies of water but by sub-surface flows (i.e. groundwater). But this is difficult to assess casually, and usually requires complicated modeling and testing of soil and geologic conditions. "Groundwatersheds" are sometimes equivalent to watersheds, but sometimes not: they depend on the 3D structure of what's going on under the ground, especially layers of impermeable clay and rock, which force water to find other ways to move.

via the Wisconsin Wetlands Association

via the Wisconsin Wetlands Association

The difficulties in assessing and incorporating groundwater into understanding flow through a landscape are honestly at the forefront of the unknown in this discipline. Hence papers in Nature like "Overlooked risks and opportunities in groundwatersheds of the world’s protected areas" with complicated figures like this one:

from Huggins et al. 2023

from Huggins et al. 2023

And recent EPA reports titled "CONNECTIVITY OF STREAMS AND WETLANDS TO DOWNSTREAM WATERS: AN INTEGRATED SYSTEMS FRAMEWORK" that are hammering this stuff out:

So, we can start by defining a wetlandscape by the hydrology: what wetlands are connected by water, whether surface or subsurface? But as with any game of linguistics, it's a good idea to remind ourselves why we're trying to do this at all so that we can make the word's definition matter, and this brings us back to the second question I stated at the beginning: what things do wetland(-scapes) do that we have previously overlooked or under-quantified?

The goal lurking under this is that at many jurisdictional levels, wetlands have legal protections on them, but those protections do not extend to the landscapes around the wetlands. This is a problem because a wetland is only a wetland because the landscape around it makes it a wetland: they tend to sit in flat valleys or hummocks, where water accumulates, or adjacent to rivers and estuaries that bring water and nutrients. So even if you can't legally destroy a wetland (please help keep this true in the USA!), if the landscape around it is heavily modified, the wetland will cease to exist. So how can we systematically identify what the wetlandscape around a wetland does for humans, to value it—and to associate a broader landscape with the wetland itself? Chipping away at any of these questions is within the scope of the DOWES project.

To me, it brings me back to a principle often discussed in river geomorphology: "process-based restoration". Early work in habitat restoration (which was often focused on rivers/streams) focused on restoring "form"—like making a straightened river meander again. But some of these projects would rapidly fall apart, the river re-straightening or separating itself from its floodplain. A river won't keep itself healthy unless its processes are healthy: with the right hydrologic regime, the right ecosystems at work, the right amount of sediment flowing through. The same is true for wetlands: even if a wetland itself is good and healthy, it will respond to its environment and all that flows through it.

Thinking with "wetlandscapes" is a step towards process-based thinking for wetlands. There's scientific work to be done in figuring out the methods for defining a wetlandscape on the basis of hydrology, as well as implementing practices of process restoration in these systems and quantifying the diverse set of ecosystem services that wetland(-scapes) do when considered holistically.

To crank up the volume a little louder, beyond the simplicity of hydrodynamics, we (the DOWES team) are interested in defining wetlandscapes as socioecological systems, where aspects of function and connectivity in the wetlandscape follow from human use. For example, this 2008 paper by Mahatanilla et al. identifies that tank cascade systems, which are ancient structures for water management in rice paddy systems of Sri Lanka, use "constructed wetlands" for passive water purification. The wetland, its placement in the landscape, and elements of its management are all interwoven with cultural uses on millennial timescales: this has big implications for how the wetlandscape is defined and functions.

Conceptual frameworks to identify and (maybe) integrate social connectivities and uses in wetlandscapes are something we're still really working on. It's a bunch of physical scientists and biologists trying to think like social scientists... but we're learning.

(Wet)landscaping,

Lukas

p.s. My personal focus at present is seeing how the Magdalena river wetlands, in Colombia, captures sediment and buffers sediment delivery to the coast (where it is smothering coral reefs and leading to increased dredging operations). Nobody's really quantified this as an ecosystem service of wetlands before.

You just read issue #101 of Gnamma. You can also browse the full archives of this newsletter.

from

from  from

from