For your next side project, make a browser extension

In a previous post I've written about why browser extensions are an amazing platform for customizing existing software. Because the browser DOM can be hacked in open-ended ways, it's possible to build extensions that modify the behavior of an app in ways that the original creators never anticipated or intended to support.

Today I'll make that point more concrete by sharing the story of a side project I made. Over the past couple years, I built a browser extension called Twemex that helps people find interesting ideas on Twitter. Twemex started as a tiny utility to improve my own Twitter experience, but it grew to have tens of thousands of users, and ultimately I sold the extension to Tweet Hunter in a recent acquisition.

In this post, I'll reflect on that experience and share some of the unique advantages (and tradeoffs) of building an extension instead of building an entire new app. I'll also share a few of the tactics I used to create a successful extension.

Most importantly, I'll argue that making an extension is a fun and efficient way to create useful software, especially when you can only invest limited time and effort. Instead of starting from a blank slate, you can start by tailoring some piece of existing software to better serve your own needs, and then share your work with other people facing similar problems. No need to brainstorm weird startup ideas or hunt for markets—just find limitations in the software you already use, and patch them yourself.

Beyond these benefits for the developer, extensions can be awesome for end-users too. Instead of needing to switch to a different app, users can smoothly integrate new functionality into their existing experience. Extensions can also support niche use cases that would never be prioritized by the original developer.

Illustration from Midjourney

The beginning

In 2020, I was a pretty heavy Twitter addict user. I got really into a strange style of Twitter usage popularized by @visakanv and @Conaw. They would use Twitter as a sort of note-taking app or memex: weaving intricate webs of ideas, using Twitter's quote-tweet and linking mechanisms for connecting related thoughts.

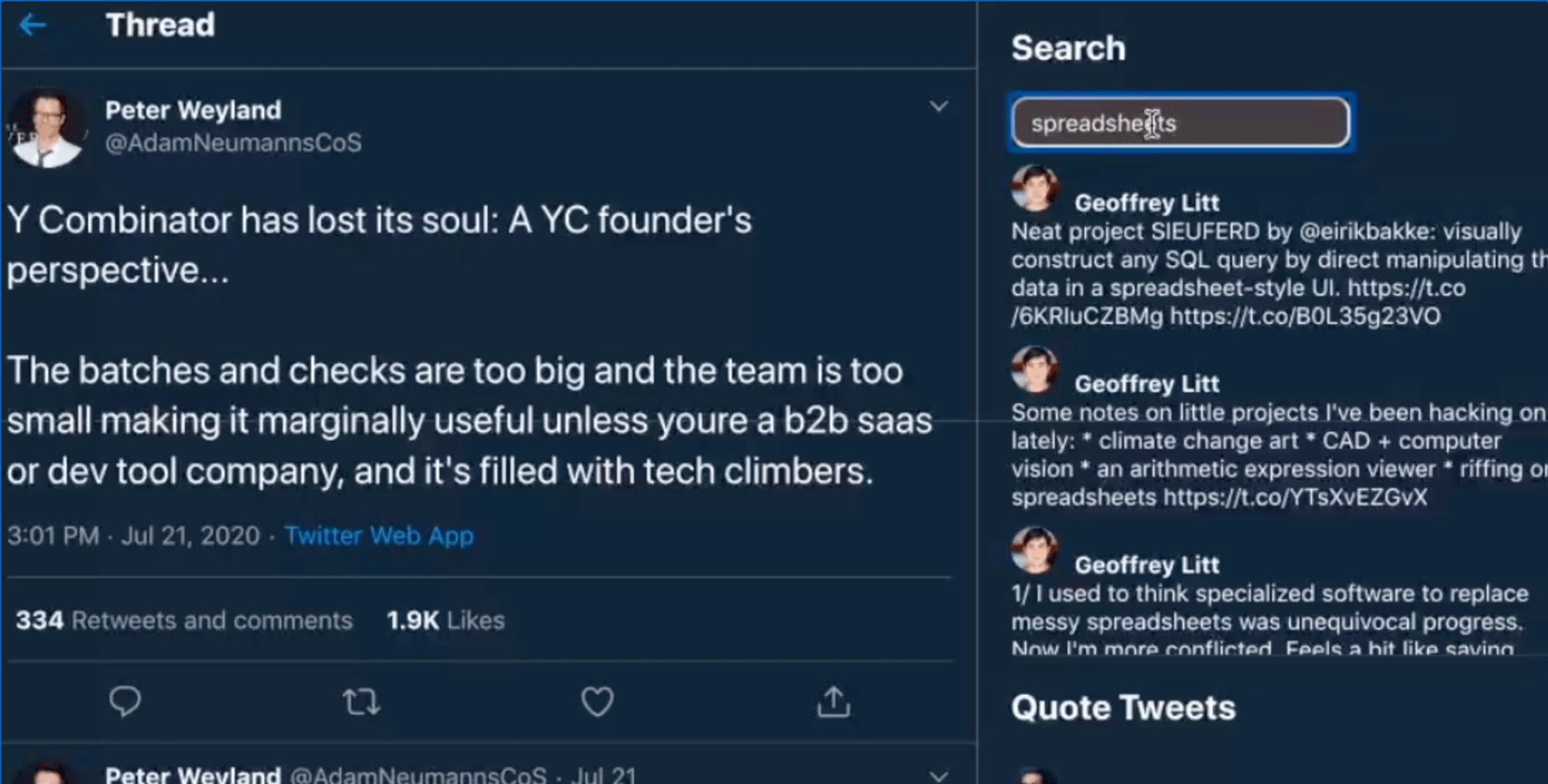

Using Twitter this way was sort of a hack, and it required some light creativity with the platform's features. One particularly important one was finding old tweets using Twitter's advanced search. For example, if I wanted to link to an older tweet I had written about spreadsheets, I would need to open a new tab and search from:geoffreylitt spreadsheets. I quickly learned that Twitter's advanced search offered tons of useful capabilities like this, but they weren't conveniently exposed.

I decided to take matters into my hands, and spent a day hacking on a simple little extension to improve the situation. It added a sidebar where I could type in a search term, and get immediate search results from my own past tweets as I typed. This way, I could easily find past tweets to link to in my own threads as I wrote them.

The implementation was dead simple. All it did was prepend from:<my username> to the beginning of the search term and send requests to the search API used by the web client. I found that the search API was fast enough to power a live search experience as the user typed, even though this live search UX wasn't exposed anywhere in the Twitter client itself.

Launch

After I used this tool for a few months and occassionally shared screenshots, a few people asked me if they could use it too. I shared the prototype, and through conversations with these early users, quickly got a bunch of ideas for more features to build on top of Twitter's search.

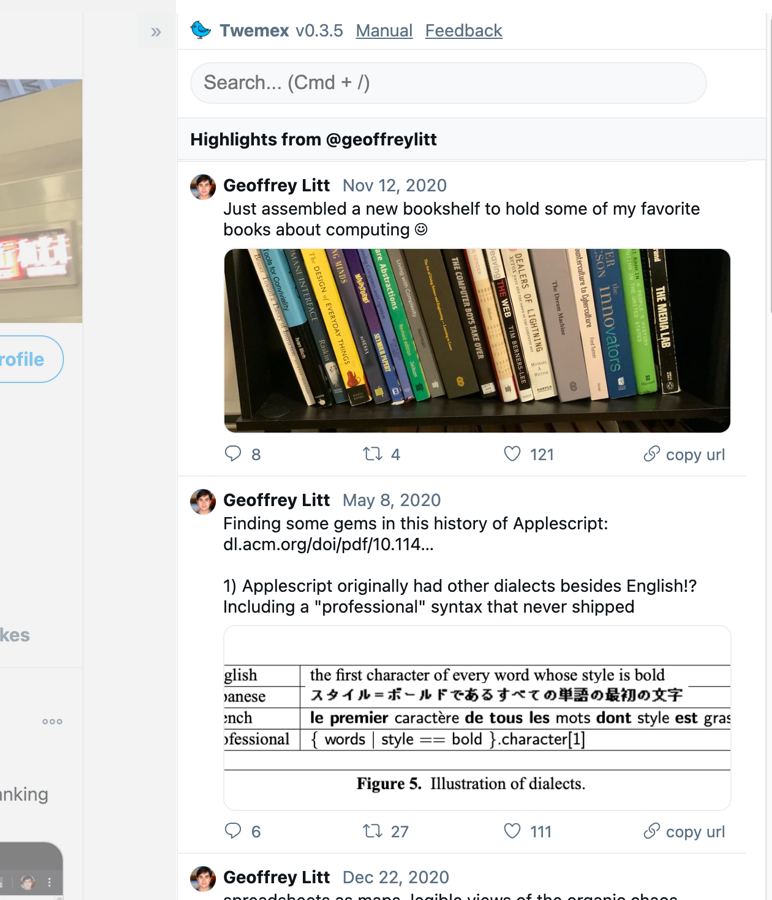

I added a few widgets that would respond to the active browsing context and passively show interesting context, without any interaction needed from the user. The most exciting one was "Highlights": a way to see the most-liked tweets from the account currently being viewed. This let you get a broader view of a new account, instead of just seeing their latest posts.

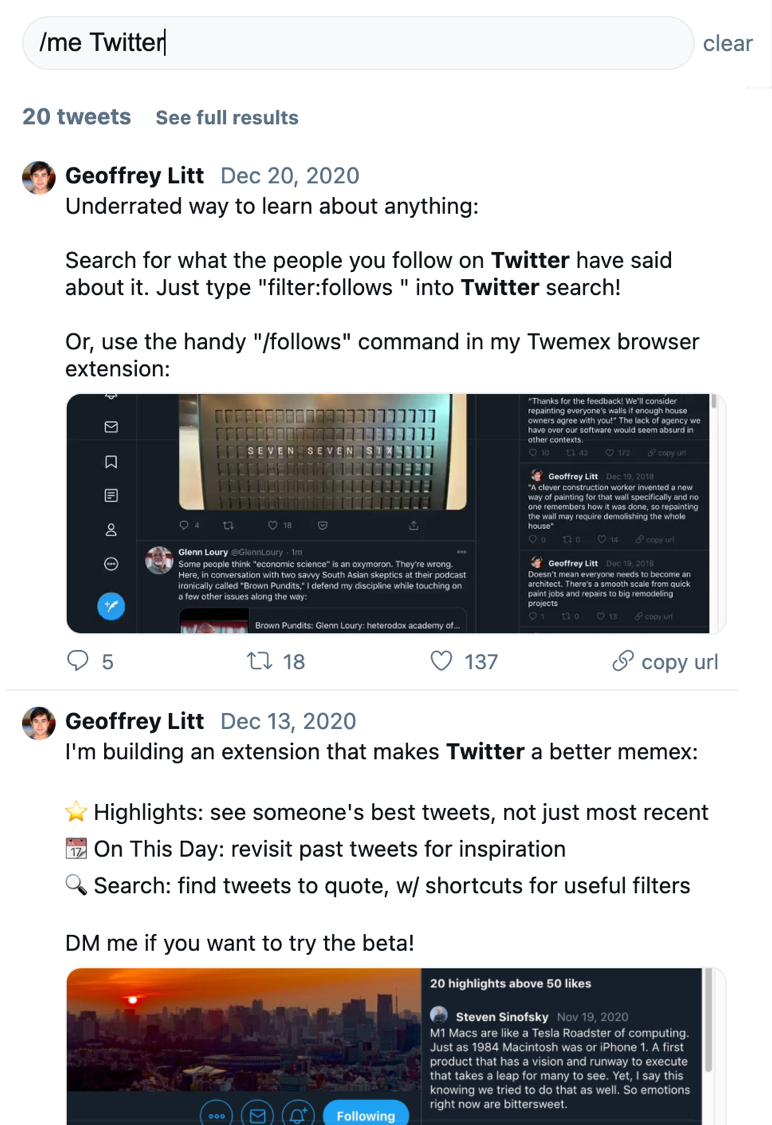

I also added a richer search keyword language which simplified the Twitter search keywords and made it easy to incorporate the current browsing context: for example, /me would search your own tweets, and /user would search within the tweets of the user currently being viewed.

One feature I found ridiculously useful was /follows, which would search tweets from people you follow. This let me treat Twitter as a personal search engine, where I could see opinions from people I trusted about any topic. This keyword was simply a shortcut for an existing Twitter search keyword, filter:follows—but saving the few extra keystrokes made a big difference in usability.

Once this initial feature set solidified enough, I got some buzz with a soft launch tweet, and expanded the beta to over 100 interested users. Everything was duct taped together: I posted the extension source on a Notion page and DM'd the link to people to sideload into their browsers.

In hindsight, this manual distribution strategy turned out to be a great idea, because DMs were the perfect way to gather early feedback. The majority of early users actually sent meaningful feedback, and I suspect it's because we already had a casual messaging channel opened when I originally sent the app. I also found that informal DMs were an efficient way of gathering feedback compared to calls or formal emails; I could easily keep conversations going with dozens of users without much overhead.

Earning the pixels

Now that I had more users, my #1 priority was to "earn the pixels": that is, to make the extension feel native to Twitter, never cause glitches, and generally offer a high-quality experience. I wanted to make sure people never had a reason to disable the extension.

It turns out the bar for this is pretty high, because people have strong existing habits and expectations. I had to build my own copy of the Twitter UI for displaying tweets, and align it as closely as possible with the real UI. When Twemex was missing features like a retweet button, people would get confused because they expected things to behave just like the native UI.

Sometimes features that might be lower priority in a standalone app become critical in an extension. For example: consider dark mode. A brilliant white sidebar on a dark Twitter site looks ridiculous. Implementing color modes, and properly syncing with the user's display preferences on the Twitter page, was a non-negotiable feature for Twemex.

I was only working on Twemex as a side project, so I had limited time on nights and weekends to fix all this stuff. For a while, almost my entire development budget was spent on quality and polish, with essentially no feature development. I think that was the right call for providing a nice experience though. Luckily I didn't have any managers looking over my shoulder asking me to ship sellable features.

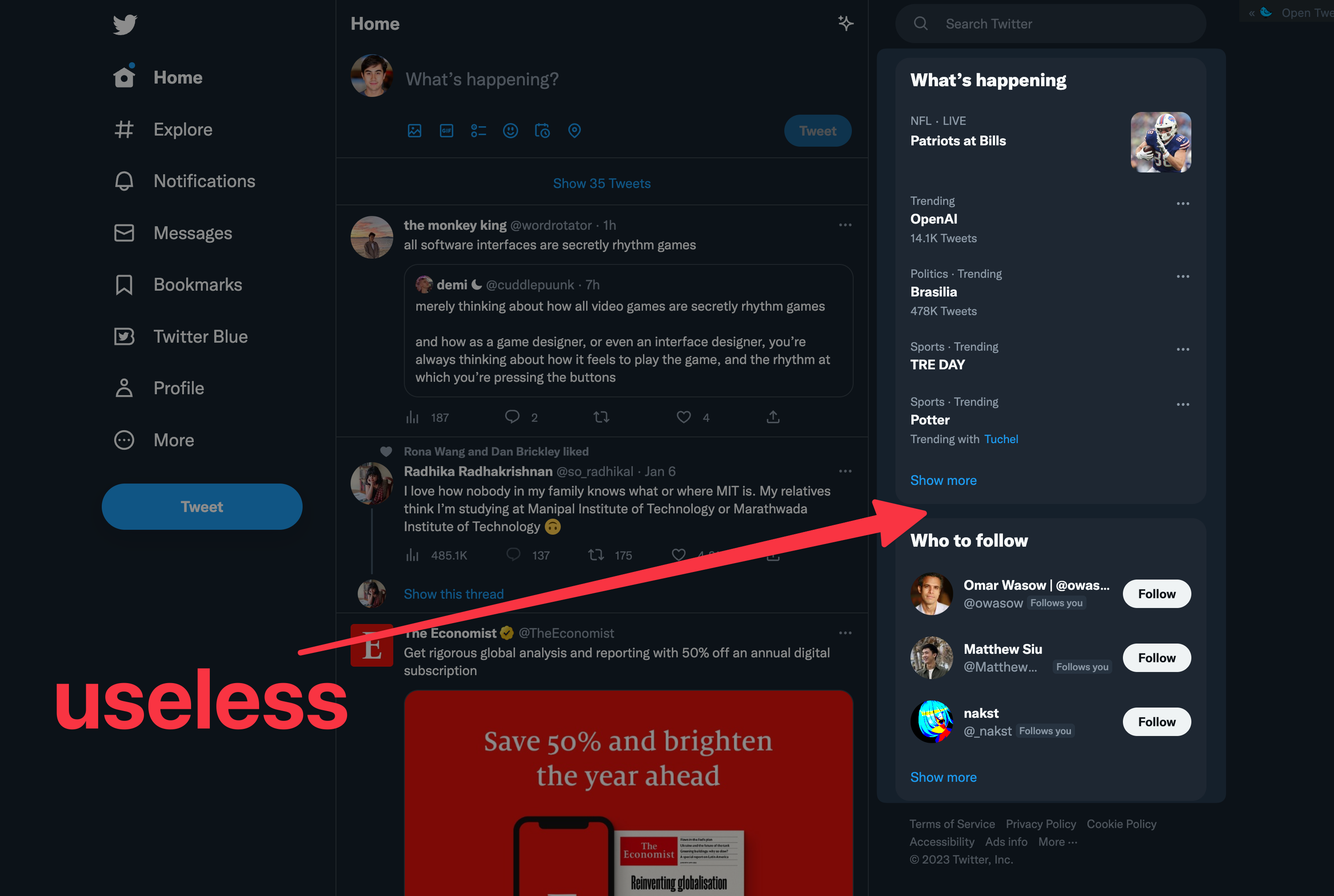

One thing that did help with earning the pixels in this case is that the real estate I was replacing on Twitter was the "What's happening" sidebar, which I (and apparently many other users) found pointless and actively distracting.

Anyway, eventually things stabilized, and I shipped a proper public beta through the Chrome store. At this point a lot of people started really loving the Twemex experience. I got dozens of reviews like:

Rapidly became one of my core features when browsing Twitter. Cuts through the noise and finds quality so well.

and

I cannot believe how broken twitter feels without twemex

and

If you aren't using @TwemexApp, you're using the "flip phone" version of Twitter.

Here's a short demo video of Twemex if you want to see more of the cool things it does. Notice how throughout the demo, it really feels like the extension is just part of the app.

Growth + acquisition

Once the extension shipped, I didn't update it very much. I would occasionally fix bugs or make minor tweaks, but I didn't have time for any more, since I was busy with my day job of doing research on user agency in computing. I also made a little website for the tool, but didn't make any serious efforts at marketing...

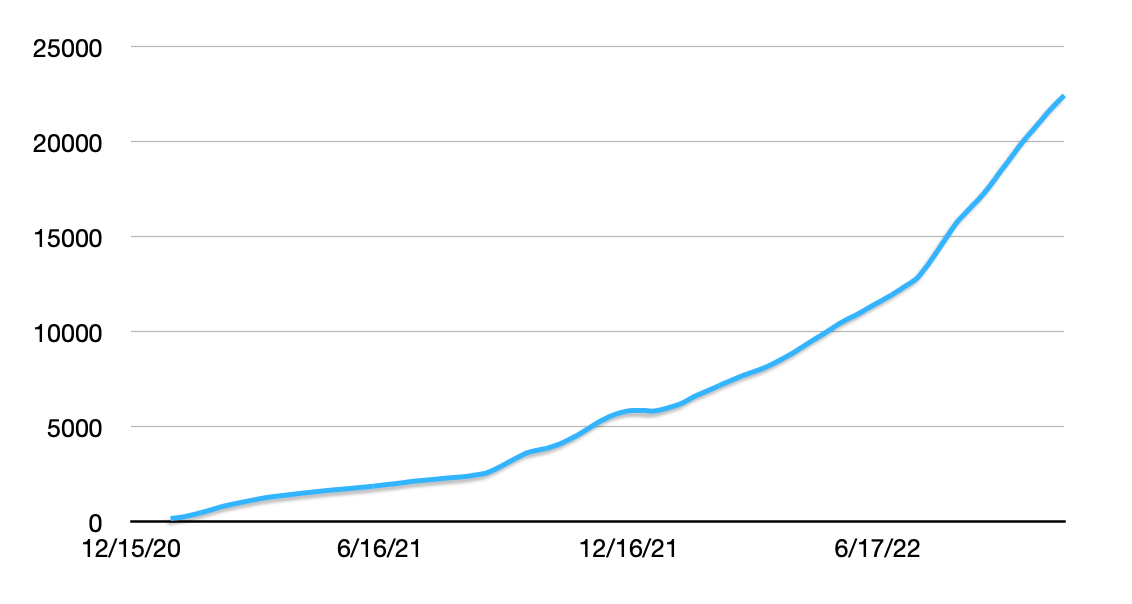

...and yet, somehow, it kept growing on its own. Users were growing reliably around 10-15% per month; after a year or two, that had built up to over 20,000 users. (This is just Chrome's report of the number of users who have the extension installed; I didn't have analytics measuring any more detailed stats on activity.)

From time to time I would think about getting more serious about the project, but I was busy with my research, and also wasn't willing to invest serious time without some kind of compensation. Many users had told me they would pay $5/month for the tool, so I contemplated making the product paid, but didn't love that option for users.

Then, in late 2022, a couple teams building Twitter-related products reached out to me with interest in acquiring the extension. I decided it was a good idea to sell, because a dedicated team could do a better job maintaining and growing the extension than I could with my spare time. I ended up selling it to Tweet Hunter.

I was particularly excited that they were longtime users of the extension and deeply understood its value. I was also happy that they planned to keep the existing functionality free, since they could use Twemex to help grow their existing product. Of course, the financial outcome was also helpful for me, since I'm currently a grad student foregoing a tech industry salary to do more speculative research.

The benefits of extensions

Looking back on my work on Twemex, I'm struck by how fun and efficient it was as a project.

I didn't set out with ambitions of creating a widely used tool, I just started with a customization for myself. And I never gave Twemex much attention; it always remained a low-priority side project below other things. And yet, I was still able to create something valuable that other people benefited from. I credit a lot of these benefits to the fact that it was a browser extension rather than a standalone app.

Here are three key ways that extensions are nice for a side project:

Easy to find an idea

Transformational ideas for software—the ones that could become huge businesses and change the world—are rare and hard to spot. Even when they do work out, they often take tremendous effort and require an appetite for risk.

In contrast, incremental improvements to existing software are far easier to find. If you're opinionated about software and have taste in design, every day spent in browser apps is guaranteed to yield a flood of small complaints, each of which could be the seed for an extension.

It's also totally okay if the complaints are quite niche or specific. My starting point for Twemex came from an esoteric usage pattern, and even after I added some more generic features, it's very far from having mass appeal. Twemex is used by something like 0.01% of Twitter's overall userbase, and that's perfectly fine.

Obviously, this line of thinking can only yield small improvements to existing tools, and it won't lead to the next big revolutionary thing. But sometimes little tweaks can make a big difference, and I find this to be an appropriate and humble mentality for a small side project.

Easy operations

I had a strict rule for this project: no operational stress. This meant no servers, and no data storage.

The tool was shipped as a purely client-side browser extension, using Twitter's backend for search. I didn't have my own user accounts; the extension would just send requests from the user's browser using their authentication credentials.

I also avoided building any features that would require storing data on my end. Data is a liability; it requires careful handling to preserve privacy, and to avoid data loss. If I had built data storage features, I probably would have tried a local-first approach to avoid operational stress.

These rules made it far easier to keep the project running without investing much ongoing effort. Of course, these aren't necessarily reasonable constraints for a larger or more serious project, but they worked for this one.

Easy growth

Getting people to use a new thing is hard, and getting them to keep using it is even harder.

The great news is, with an extension, the flywheel isn't starting from scratch. Once a user installed Twemex, they would automatically see the new sidebar whenever they visited Twitter. For the power users who were the most likely to use Twemex anyway, this meant that their existing habits would seamlessly grow to include Twemex.

Very often, people would tell me they had forgotten that Twemex wasn't part of Twitter itself. I think this also points to the benefits for users: would you rather have to learn a whole new interface, or just have your existing one seamlessly improved?

The flip side of this is that the extension has to earn the pixels. Any glitchiness or quality problems that would mess up the core Twitter experience would lead to an uninstall. Most of my time working on the extension went into making it feel native and removing any problems that would actively degrade from the experience.

In summary, building an extension gave me access to an easy idea, easy operations, and easy growth, relative to building a larger application. It still took careful design work and lots of iterations to reach a good product, but the leverage from the hours I put in was pretty high.

The drawbacks

I also found that there are some key tradeoffs to grapple with in extension development.

Platform risk

With any extension or plugin, there's always platform risk since you're building on top of someone else's app. This could range from day-to-day instability, to getting completely shut out or replaced by a first-party feature. Twitter in particular has an infamous history of treating third-party developers poorly.

Interestingly, Twemex doesn't actually use the official Twitter API, so it's subject to a different kind of risk than official third-party apps. On the one hand, there's no API key, and Twemex can access all the APIs used by the first-party client, which is super convenient. On the other hand, because it's building on an unofficial, reverse-engineered foundation, there are no guarantees at all about when things might change underneath.

Luckily, I didn't have too many issues, perhaps because Twitter didn't change its core features very much while I was working on the tool. I generally tried hard to minimize the coupling of my UI and Twitter's DOM, and did slightly fancy things in some things in service of reliability—for example, my code for detecting color themes from the site uses ranges of colors rather than exact hex values, to be resilient in case Twitter were to slightly tweak their colors.

In some ways though, maybe this platform risk can be an advantage for a side project. The platform risk might be too great to build a whole business on top of, but for a lower-stakes extension it's fine.

Another thing worth mentioning is that it's getting harder to engineer browser extensions well as web frontends become compiled artifacts that are ever further removed from their original source code. Semantic CSS classes are mostly gone these days; stably addressing UI elements is hard.

The Chrome extension platform is flawed

I'm used to building web applications where you can ship an update anytime, especially when something is broken.

In contrast, I found that distribution is miserable on the extension platform. Reaching most users requires going through the Chrome Web Store, which has an opaque manual review process that can take anywhere from a couple hours to a few weeks. Not being able to ship updates quickly meant I had to be far more diligent about QAing releases.

It seems like Chrome may be improving this situation recently but it's hard to tell. I found it really helpful being in Taylor Nieman's Slack channel for browser extension devs to ask for advice and generally commiserate.

There's also been a ton of angst recently around the move to a new extension format, Manifest V3, which has also been delayed due to some of the turmoil. I won't go into the details here, but the overall impression I get is of a platform with tremendous potential, but somewhat disorganized and neglected under current management.

Conclusion

Software should be a malleable medium, where anyone can edit their tools to better fit their personal needs. The laws of physics aren't relevant here; all we need is to find ways to architect systems in such a way that they can be tweaked at runtime, and give everyone the tools to do so.

Beyond the pragmatic efficiency benefits of building a browser extension, I would argue that it's simply more fun to engage with the digital world in a read-write way, to see a problem and actually consider it fixable by tweaking from the outside.

So, if you're a programmer: the next time you come across an annoying problem on a web app frontend, maybe consider writing a browser extension to make it better, and then share it so that other people can benefit too.

Related

- I gave a talk called Using Twitter to Cultivate Ideas, where I went into more depth on some of the philosophy behind Twemex.

- I've written before about the promise of browser extensions as a platform, and democratizing the power of extensions

- I'm excited about Arc Boosts, an attempt to integrate user scripting and customization deeply into a new web browser

- A Twemex user recorded a nice demo showing off and reviewing the extension in more depth