What I'm thinking about for 2026

the big ideas i'm trying to wrap my head around

First Alternate: A Lindy Hopper's Newsletter

As many of you know, every year since 2022 Helen and I have made a in/out list for the lindy hop scene. This is not because we aim to be tastemakers, but because we are jokesters and we’re opinionated and over the years, opinionated people find us. The conversations surrounding the in/out list always end up revealing some themes: frustrations, hopes, and “it is what it is” observations that everyone seems to be feeling. In thinking forward to 2026, beyond concrete projects, I’m thinking about some of those, too.

(Not) dancing for the camera

In so many conversations, not just over Lindy Focus but throughout the year, I heard how tiring it is to watch dancing that feels like its purpose is to be watched. I’m not talking about performances here, I’m talking about social dancing.

This isn’t a new complaint; it’s been going around at least for the past couple years. If you listen to Marie N’Diaye on Integrated Rhythm, you can hear a great argument against social dancing as performance from the perspective of Black social dance culture: most social dances, she says, should be hangs, should be able to be done between drinks and while chatting. (I’m paraphrasing heavily here).

From another angle: in talking to Michael Seguin, he said (and I’m paraphrasing heavily here, too) that there’s a loss of intimacy when you dance like the camera is on you all the time, that people doing that forget that the only person you’re really trying to impress is your partner, and what impresses your partner (especially the feeling of dancing with you) is probably not the same as what impresses instagram.

In the ULHS video session at Focus this year, Karen, Michael, and Jerry kept stressing that yes, these dances got recorded on their camcorders, but that if you were in that video, it’s possible you never saw it again. You could make a huge mistake, or land the coolest trick of your life, and it was ephemeral.

I feel a small version of this: I started dancing in 2012, and I remember how filming our dancing was reserved for recap videos, auditions, performances, or just “fun,” since there wasn’t such an easy way for some random video of your social dancing to reach thousands of people in your broader community. It wasn’t until 2018, when I decided that I was tired of being a dancer with a reputation for feeling great and looking bad, that I started posting Helen’s and my practice to social media—and at the time I was one of the only people I knew doing that.

I find this gripe totally reasonable, and I find it really complex and thorny. Not to do “and yet you participate in society,” but we are all being watched all the time, and we’re all being judged on what we do by the people who are watching. Everyone expressing they don’t want to see people perform their social dancing is clearly watching a lot of social dancing. It makes sense to notice you’re being watched, and to want to be watchable.

Not to mention, it is nice to be able to see how your dancing is doing. You don’t need to be recording and watching your dancing back all the time, but sometimes the only way to figure out what’s not working is to see it not work—or the reverse, sometimes it takes seeing yourself do something you think looks wack to realize it looks fine, actually.

But the strongest argument, apart from the cultural one, that I hear against constant filming and performance, is that it discourages risk-taking. No one wants to eat shit on camera, potentially for their friends and peers all over the world to see. This incentivizes playing it safe, not debuting anything until it’s polished. And that does bum me out! All the stuff you see in clips from the early 2000s that makes you jump out of your seat and go “what the fuck was THAT?” even when it doesn’t totally work or the shape they make kinda makes you laugh? I want to be able to do that!

I miss the feeling of being new and not knowing what I was and wasn’t “capable” of doing, and trying silly stuff with my friends without worrying about how it looked. Whereas with YouTube you at least had to know a little about what you wanted to see to be able to find it, with Reels and other short form content, creators and consumers alike are incentivized toward what the algorithm likes. I can’t imagine being new now, and having endless lindy hop content served up to you to compare yourself to.

And even for myself, now, I know how having eyes on me makes me hyperaware of what I do on the social floor, and the stuff I put online isn’t always the stuff I’m the most proud of or interested in doing. On the bright side (in my opinion): unless your audience is Tyedric’s or Nils and Bianca’s size, most of us are not going to be the first video anyone sees of lindy hop, so I think we can all take a collective breath of relief to not have that pressure (and to appreciate the enormous amount of pressure people like Tyedric are under).

And I simply don’t trust the algorithm as a tastemaker. What would the Instagram algorithm have made of Stefan and Bethany or Ann and Ryan? I’d rather the community be the arbiter of its (preferably many, diverse, interesting) tastes.

All this said, I love performing, and I don’t think dancing to perform is bad. But I am entering this year trying to be intentional about it, rather than doing it by default, and to see if I can take some more risks that way.

Integrating cross-training

It’s pretty exciting to me that lindy hoppers seem to be more willing to branch out than they have been in recent years. It’s not cool to just be a lindy hopper anymore, in a way that I think is mostly exciting. I’ve spoken about my house and hip-hop classes; I’m also going to a balboa event this year. I’ve seen people’s clips from their forays into waacking, twerking, West African dance, tap, and hustle. And of course, we’re in another big Westie moment.

But what I do think lindy hoppers struggle with is letting those styles affect how they do lindy hop, because I think we still have a tendency to see it as this siloed-off style. But I love seeing and feeling when people really let the dancing they’re doing change how they move everywhere: you probably won’t see me at a West Coast dance any time soon, but I love being led in some crazy westie shit. I love when a bal dancer swings out and there’s a little “too much” rotation at the end of it. I love the flow and control of a house dancer on the social floor, and I love how even the little I did last year opens up my upper body in my lindy hop. If you’ve got it, be proud of it! Let it change you!

A little conflict is necessary

I love good conflict. In my personal life, I’m pretty unafraid of it. Call it my neurodivergence or whatever, but I’ve never really understood needing everyone to like you, and I find the discomfort of avoidance so much more unbearable than the discomfort of dealing with an issue.

All of this has made the lindy hop scene a pretty uncomfortable place for me over the years. With the help of my very Midwestern wife, I’m much less likely to run headfirst into a conflict than I used to be, and that’s probably made me more palatable and less scary.

So it surprised me to hear from multiple people that they wish there was more low-stakes beef, and more stated, healthy tension. Jerry reminisced fondly to me about how tense things used to be between the superstar up-and-comers.

I think I know where this comes from. If you’ve been around long enough, you get used to high-stakes conflicts that feel like we’re defending the values and safety of our scene, such that when they come up it feels like squashing a bug: no, you shouldn’t call it East Coast Swing; yes, it’s obviously racist to [fill in the blank]; no, he doesn’t get hired anymore because he has credible allegations. They’re necessary conversations, and they’re also now conversations it feels like we as a community know a little bit about how to have (a welcome change from a decade ago), and that’s pretty exciting and encouraging.

But with all the energy put toward that, sometimes it feels like any other garden variety unpleasantness is not to be looked at or dealt with, and it means sometimes it can feel like we’re swimming in a big passive aggressive soup. It feels impossible to acknowledge even to a trusted friend that there’s a guy in your local scene you just plain don’t like dancing with. It’s difficult to have a friendly rivalry with your peer you see at every contest weekend when you have to pretend it’s all friendly and none of it is rivalry. It’s much more common to make uneasy conversation with someone you don’t like at every event for years than to politely excuse yourself from the conversation and save yourself some annoyance.

What often happens instead feels markedly worse: you have to pretend you like everyone, and sniff out, like a secret agent, people with whom it’s safe to confess that “I just think that guy’s a dick,” or “I dunno, I’ve tried hanging out with her and we bounce right off each other.” And if someone’s behavior really is off-putting to a lot of people but not grounds for ejecting them from a scene, it becomes a whisper network, sidestepping the possibility for actually telling that person (who might not know!) that they might want to think about changing their behavior.

I think some of this also comes from people’s feeling that lindy hop is their escape hatch for “real life,” and so it would be nice if the community or the power of dance were able to paper over the difficult feelings we all have for each other. That attitude creates this oppressive, false positivity, especially for those of us who are marginalized who don’t have the option to leave our troubles at the door of the social dance.

I personally think it’s healthy to acknowledge when something is stuck in your craw, and sometimes it’s healthy to acknowledge it to that person. I made one of my best friends in the dance scene only after we confronted one another about each other’s standoffishness.

But more often, it’s fine to just have a conflict! Sometimes you just don’t get along with someone, and that’s fine and doesn’t make you or them a bad person. We’re all different people with different value sets and personalities, and sometimes some of those don’t mesh for reasons that are not because one or the other of us is a moral failure. Being in a community doesn’t mean you have to like everyone in it—it means you’re necessarily not going to be able to like everyone, and you have to be able to live with them. There’s lots of ways to share space with people you don’t like that don’t involve pretending you do like them. Don’t bully anyone, but I don’t think the answer to “I don’t like this guy” is “I must force myself to be their friend.” Live with that discomfort instead, it’s shockingly livable!

Developing taste

In the same vein as all of these points, over Lindy Focus I kept hearing calls for more different, interesting work. “Lindy hop has become homogenized” has been said since at least the nineties, and it’s true to some extent every time someone says it, but I think with the sheer volume of “content” out there these days, it is harder than ever to develop personal taste. It’s hard sometimes, in talking to people, to glean what specifically people like, why someone’s dancing is inspiring to them. And, to the previous section, I rarely hear anyone saying why they don’t like something.

All great art moves forward with criticism, positive and constructive. Not everything being put out is remarkable, and not all of it is going to work for everyone. I find it fun and interesting to talk to people about what they’ve seen recently that they really loved, or something they saw that didn’t hit for them. The more specific, the better sense I’m able to get of how that person thinks about dancing and what they value. These are difficult conversations to have, because we all know each other, and you usually end up talking about a friend’s work. But it’s possible to respect someone, even like them, and have a complex view on their artistic output.

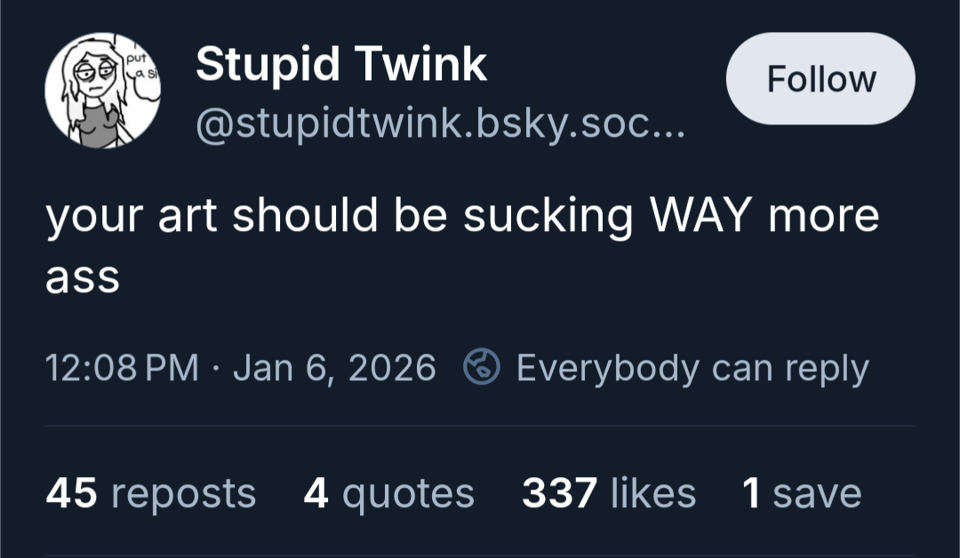

And it’s not all about what you don’t like—specificity makes positive feedback much more meaningful. It’s one thing to say “I love your dancing!” and it’s another to say “your dancing looks so relaxed,” or “you have a wonderful way of articulating your arm.” (Those are two things people have said to me, and I remember who said them much easier than I remember vague compliments!)

The more thoughtful and complex your own taste is, the more you’re able to point to what does and doesn’t work for you, the more intentional you can be about what you do, and that’s one of the ways we get more interesting, more specific art.

This all comes out sounding a little cynical, I guess, but I don’t mean it to be. What this all adds up to is a hope for a bit more space and patience for nuance, mess and mistakes in a world where those things are increasingly disincentivised. Nuance, mess and mistakes are three of my favorite things about jazz, so hopefully it’s just more of what’s already there for the taking.

You just read issue #14 of First Alternate. You can also browse the full archives of this newsletter.