You Can Just Look Stuff Up! Honoring Black History Month through DIY historical research

You Can Just Look Stuff Up! Honoring Black History Month through DIY historical research

Your local history of race is probably full of open questions. Receipts are out there.

In the small New England coastal city where I grew up, an African Burying Ground in the middle of downtown was paved over and desecrated. A memorial park was created in 2015 to honor the dead interred there, but for the historical people who used the cemetery, the damage was already done. Common belief when I was growing up held that this was a crime of the distant past, committed by people long dead, and then utterly forgotten.

You can just look stuff up

It happened by degrees. The desecration started probably in the eighteenth century, when a thriving mercantile economy on the riverport fueled expansion of the city center into agricultural lands once known as the Lower Glebe. The mercantile economy was deeply implicated in the abduction and trade of enslaved people, with many of the city’s founding families growing rich off the trafficking of human beings. So-called “auctions” of enslaved Africans took place only a few blocks away on Daniel Street; whippings took place up the same road near what is now called Market Square.

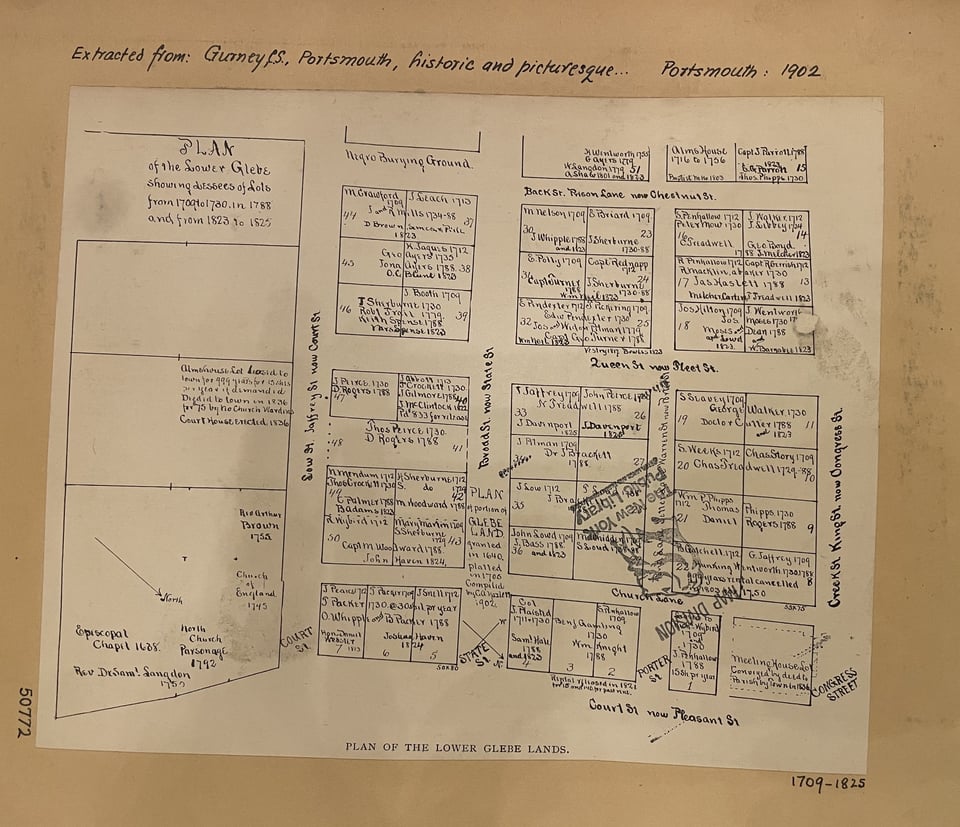

The map below is proof that white people knew what they were doing when they built over the hallowed ground of the African cemetery. It’s a historical map of Portsmouth, New Hampshire, depicting an outlying area of downtown subject to gradual expansion in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, reproduced by a local print professional in the early twentieth. To the right of the word PLAN in the top left corner, you see an area—it was called Chestnut Street when I grew up—with the label “Negro Burying Ground.” C. S. Gurney, who reproduced this map, published it in 1902 in Portsmouth, Historic and Picturesque, a directory of local places, drawing from town histories that were well-cited and popular with local gentry at the time. The book and the map it contained were referenced by scholars in and around Portsmouth throughout the twentieth century. We can assume that they saw, registered, and overlooked the label printed across present-day Chestnut Street many times over.

Without any doubt, knowledge of the African Burying Ground was readily available to every generation of white capitalists and city administration who had a role in developing this land. The cemetery’s desecration was no accident, but rather a deliberate atrocity. The evidence was in plain sight from the moment the first grave was paved over—all it took was somebody to look into it.

I accessed this map at the Map Collection of the New York Public Library, 42nd Street research branch, the big one with the two lions out front. I talked to a librarian and she helped me request maps of my hometown, then I waited like three days and they were ready to view. I brought my friend Alex with me for company and we took the train up from Brooklyn. I peer-pressured her to sign up for a library card. We spent the afternoon in a gorgeous, high-domed chamber looking at maps. After looking at the maps, we checked into the Treasures Exhibition and looked at a bunch of pre-publication James Baldwin manuscripts. It was dope. The whole afternoon cost zero dollars.

I am far from the first person to write about this cemetery in my hometown. The history’s already been discussed by authors in a variety of disciplines, from historians Mark Sammons and Valerie Cunningham to Portsmouth Poet Laureate Erine Leigh. I accessed their work at the library too, and it helped put the African Burying Ground on my radar. The years-long effort to re-consecrate the land, led by a multi-racial group of activists, historians, and faith leaders from New Hope Baptist Church (Portsmouth’s historically Black congregation) was finally completed in my sophomore year of high school. The area is now closed to auto traffic, an open-air memorial and historical exhibition on local Black history.

My research at the library was not a profound discovery for the world at large, but it was a pretty big deal for me personally; I already knew this document existed thanks to the work of local Black historians, but I had assumed that the proof was locked away in a university archive somewhere. Nope. It was just waiting there for me at the public library, with millions upon millions of other primary source documents freely accessible to the public. I learned a lesson that day that I’ve learned many times over, before and since: When it comes to history, you can just look stuff up.

History does not belong to academia

I’ve been studying Portsmouth’s local history for five years as a DIY historian—meaning I have no institutional affiliation right now and no professional credentials—and I’ve had my fair share of difficulties in accessing literature. But crucially, almost always, the stuff I have trouble accessing is secondary literature. The work of historians and social scientists, real ones I mean. Ones with masters degrees and professorships. Those who don’t answer your emails unless you’re a matriculated student, and even then it’s a soft “maybe” on whether you’ll ever hear back. When I say “You can just look stuff up,” I don’t mean to insinuate there is not a profound, unconscionable problem of gatekeeping and accessibility in the field of history. Some stuff really is just locked away. Elite control of academic knowledge is real, and very racialized. In many ways, this same phenomenon is what keeps people from finding out about the horrors of US anti-Blackness. By throttling access to history, and systematically preventing less advantaged people from receiving an education in historical methods, academia forms an inextricable part of white supremacy in this country. Even as a white person trying to study history with a fuckin’ B.A., I run up against the high walls of academia and am repelled on a daily basis.

History, as an academic field, is an ivory tower without an ADA-compliant ramp. It’s got no elevator, and the staff look at you with suspicion if you’re poor or trans or, especially, not white. All the signs are in English and no one wants to translate for you. It only opens at weird hours so you gotta access it at like 10-2 on a weekday when most people are supposed to be at work. Oh, and it costs like a thousand dollars a day to get inside.

… But history—meaning stuff from the past that you can look at and study—is everywhere. The discipline is almost entirely DIY-able if you have a library card. Yes, it can be difficult to get your hands on some of the localized or rare materials you might need, but go into any public library and there's a whole staff dedicated to helping you do just that. History is not like math or science; you don’t need a laboratory, or a faculty advisor, or even necessarily a specialized skillset. You do need to be willing and able to read a lot of dry materials, a lot of which are probably undigitized. You will need to ask questions. But if you do it right, the question asking is actually the best part. I may be biased, but librarians (in New York at least) are mostly very willing to help answer your questions. You can also find history in the lived experiences of the people around you; oral history—my favorite kind—is now easier to conduct and preserve than it has literally ever been. You got a phone? You got neighbors, friends, or elderly parents? You can be an oral historian.

And I would argue, especially in the month of Black history, that you should be an oral historian. Or a historian of maps. Or a historian of music, film, or television. Or your neighborhood, or your school or workplace, or your family, or an internet community you’re a part of. Search engines can easily hook you up with lists of books to read by Black authors this February; stories and poetry collections, plays and essays and biographies of Black historical figures—but if the interest moves you to look and learn then why stop at just reading? For every book already written, there are handfuls of primary sources—sometimes the book itself is the primary source—that tell you something about the past that you didn’t know before, and that nobody has ever looked at in quite the same way you’re looking at it now. Your interpretation of that info, when placed in the context of what others have written on the subject, is a novel work of history.

DIYing history

You do not need to know everything about a topic before you research or write about something. You do not need to have read every book about, for example, the city you grew up in if you want to speak about it. You should humble yourself before the scope and depth of existing knowledge—especially if you are, for example, a white person writing about Black history—but you don’t need to be so scared that you walk away or never approach the topic at all. DIY research is all about learning. You don’t need to pretend to be an expert! All that’s necessary is that you’re respectful of the knowledge and perspectives that already exist, clear about where and how you’re coming to the discussion, and willing to listen.

While it’s unnecessary to disqualify yourself from looking into a topic from the jump, you should absolutely let your personal backgrounds, geographies, and identities guide what you choose to study and how you choose to study it. Some topics are more appropriate than others for a prospective historian to explore.

In my own personal approach to Black history in the place where I grew up, I heavily referenced existing oral histories from members of the local Black community but conducted none myself. When I conducted interviews with elders in my community, I did so on a relational basis, finding research contacts through extended family, friends, and neighbors. The people I ended up conducting oral histories with were mainly older white people I already had at least a passing relationship with. Because of that existing trust, I was able to gather some very candid perspectives on local race relations from my elderly white neighbors, painting a much clearer picture of race and racism in my hometown than I had before I started the project. I hope these perspectives will be useful to future historians who wonder how white people spoke and thought about race and neighborhood life in their own time. As a white researcher, there are sensible and appropriate limitations on how I’m able to study and speak about Black history; but in such an enormous field, it’s always possible to find corners of the racial past that you’re well-suited, or even uniquely suited, to study.

Experiences like the one I had in the Maps room of the library are why I love studying Black history in the United States. All at once haunting and compelling, very old and deeply current, repulsive in what it shows about this country but liberating in how it helps design our revolution, Black history is something that we should learn not only by reading, but also by doing. If you have a library card, an internet connection, and the ability to read and think for yourself, you’re already on your way. Especially in the study of marginalized groups, some of the most useful histories come not from the halls of academia, but from the grassroots, researched and written by people on the ground with a personal stake in the past and its living memory.

thanks for reading and happy Black History Month! you can find me on substack @everzines and on IG as well. my bluesky doesn't link for some reason but i'm there by the same handle. i would love to be in touch with you about your DIY research or answer questions about my own at eviewrites@duck.com. until the next post,

your parasocial friend and comrade,

evergreen<3