A blank page is like a forest to a man on the run

n the power of writing and creating alongside others.

Write Like a Human Issue 002, 3 July 2021

There's a keyboard on my desk.

I'm using it to write this. There's another keyboard in my back pocket, which I used 345 times last week - an average of 49 times a day.

Most days, I spent just under 2 hours staring at this second keyboard, which is also a phone.

In my front pocket I keep a pen. Right now, I have four pens: V5 Hightechpoint rollerball pens. With pens like these I wrote by hand last year approximately 96,000 words in a series of notebooks.

You may write more than this. You may write less. But I bet that, like me, you take for granted your capacity to write whenever you like.

Sometimes, I ask myself what it would be like to have that taken away from me. Not in the sense of "where did I put my phone?", or, "does anybody have a pen that works?"

I mean, to have somebody deprive me, perhaps forever, of the means to put words down and share them with readers.

Who typed this?

In the Soviet Union, typewriters were made so that each one had a very slightly different output; if the authorities didn't like something, they could find out who typed it.

For this reason, free-spirited writers prized typewriters that had been manufactured abroad - mind you, being found in possession of such a liberating machine could itself get a writer in trouble.

In the gulag, writers scratched out poems on bars of soap.

Just imagine that: you can forget all the convenience of cut and paste, variable fonts and spell-check. When you write on a bar of soap you have no more space than the palm of your hand.

And I've written more than that already, in this email.

When writing on soap, I imagine, you must choose your words with enormous care before you start. And that's a good thing, by the way: the sheer labour, and the brevity of your output, should make your words easy to remember - and you'll need to remember it, because in order to stay safe you'll probably decide to dissolve all your careful work under a tap.

In light of this, you will understand why one Soviet writer described a blank piece of paper as, "like a forest, to a man on the run".

“It’s hard to write”

I can't tell you how many times I've heard people talk about how hard it is to write.

As you can imagine, they never mean that it's hard because the authorities might seize their work and have them executed.

No, people in my world, weirdly, seem to find writing difficult in almost exactly inverse proportion to how convenient and easy it has become.

As if, lacking the reasonable excuse of resource shortages - no quill, ink pot, or paper - we rely instead for our excuses on the shoddy matter of negative self-talk.

To adapt the metaphor: we're like a man on the run who, coming to the forest, stops because he has Imposter Syndrome, worries that he's "not very good at running through a forest", and that people might disapprove of the way he does it.

Madness!

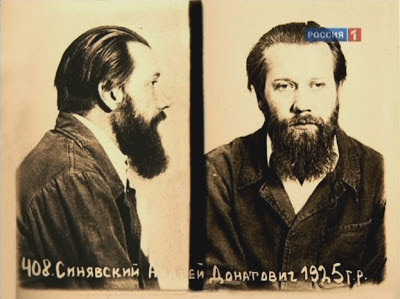

The Soviet writer who came up with that line about blank paper, Andrei Sinyavsky, was put in the gulag for writing something unacceptable to the authorities.

Despite this, despite being burdened with hard labour all day, and despite having his letters read by a censor, Sinyavsky somehow managed to write and smuggle out of the gulag, in letters to his wife, three books.

Three!

Now hat's what I call a writer.

Last time I published this newsletter, Write Like a Human, I mentioned that I was planning to do a very particular challenge with friends.

Together but separately, we would publish something every weekday, for exactly a month - then stop.

I'd only recently come across the concept of a time-limited email newsletter - a "pop-up" newsletter - and I was excited to see how it worked. I wondered what the format might make possible.

Three people took up my challenge.

We published our own material to our own different audiences, and (if we wished) subscribed to each other's pop-up newsletters. (I did wish.)

Before going into what happened, I should explain a little more about why I decided to do this challenge. There were two main reasons.

To delight my literary agent by publishing material about public speaking, the subject of my latest paperback, A Modest Book About How To Make An Adequate Speech. "Keep talking about the book, as if it just came out today," Jaime says occasionally. Well, giving myself a daily publication schedule provided just enough structure for me to do that. I chose as my theme "Great Speeches of the 20th Century", the title of a box-set of speeches published by the Guardian in 2007, and recently discovered in a second-hand bookshop.

To gather evidence that it's more fun and more productive to create work alongside others - together, but separately. I've done a fair bit of that in the past, ad hoc, but never so much as in this last year-and-more of Covid (more on that shortly).

I can't speak for the individuals who published pop-up newsletters alongside me, but we did compare notes occasionally, and I think we had similar experiences.

Such as: we discovered that the great fear of getting started, and of not being "ready", was soon replaced by a frenzy of creating material.

It's also fair to say that everybody experienced a dip, roughly half-way through, and wondered about packing it in. This is where it came in most useful to be doing it alongside each other.

If I gave up, it might demoralise others. If I carried on, it might encourage them. And vice versa.

Another thing I noticed was that we shared ideas and approaches, and even sometimes referred to each other in our emails - because, perhaps inevitably, we started to see patterns in our output.

We all actively sought replies from readers, and built those replies into the following days' emails - we were discovering that a pop-up newsletter is a lot more current, more NOW, than a series of blog posts that people may not see till long after they've written.

(If they see them at all.1)

My own newsletters were between 500 and 1000 words each. Which means that, over the month, I wrote 10,000 to 15,000 words that I wouldn't have written otherwise.

I found new ways to think about my subject, and I found new readers who shared yet more ways to think about it.

I hope that, as you read this, you are thinking about how you might try something similar.

.

When I started this Write Like a Human newsletter I chose the name Everyday Writing, because I'm interested in the overlap between Writing with a capital W, of the kind perpetrated by (say) Henry James, and everyday writing like To-do lists, which we don't generally think of as writing at all.

Recently, a woman on a writing course asked me how to be creative in the times she had set aside for being creative. The question is not particularly uncommon. My answer was to say that it's hard to be creative when you think you "should". Creativity resists being compelled.

Later, in conversation with a friend, an alternative reply came up: what about taking creativity into your whole life, not just fragments of time you have set aside?

What does it say about a life that you must set aside time to be creative? To be creative is to be alive: everything else is just going through the motions, like a zombie.

We only get one life, but we get lots of stories, and ideas. Often, we believe they're not very good - but that's because we haven't worked them up in the writing. I rarely have a clue what I think about anything until I've written about it.

The great genius of Sinyavsky was to disguise his Writing-with-a-capital-W as everyday writing, in the form of letters to his wife.

The two kinds of writing are implied in the word journalism: generally, when we use that word, we mean the stuff that gets into papers and TV news, but the dictionary tells me it also means writing in a diary, or journal.

Well, for the last few months, I've followed a new (to me) system of keeping a paper journal, and it's been transformative.

For example, over the last few weeks I've spent a lot of time compiling and writing a detailed half-year report for members of my SPECIAL PROJECTS.

This included month-by-month breakdowns of

Writing projects

Speaking projects

Art projects

Projects sharing my process/encouraging others

I won't repeat it all here, but I will say that the process of auditing everything was powerful: I was astonished, if I may say so, to find how productive I've been.

To give just one example: In six months, I wrote 123 posts on my website. By comparison, I wrote just 40 in the whole of 2020. Perhaps as a result, the website had 52% more visitors, and the average duration of each visit was 63% longer.

I also audited my podcast, artworks, social media output, emails, and much else. But the point to stress here is not the output but the audit process, which was made terrifically easy by the new journaling system I use.

Earlier this week, I explained it on Zoom to a SPECIAL PROJECTS member; and I thought it might help others if I shared the basics on my website, here: https://flintoff.org/what-a-relief-to-write-tasks-events-and-insights-on-paper

I hope you find it useful.

.

Before I go, a word about SPECIAL PROJECTS, which is intimately connected to the idea I raised earlier - about working alongside others, but separately.

In 2020, with other work disappearing due to You-Know-What [2025 update: I mean, Covid], and despite failing to qualify for the UK government's Self Employed Grants, I somehow got through, kept paying my bills etc, thanks to the support of seventy-two individuals and organisations who paid for my work. Some did that just once, others several times. The largest payment was for £3,995. The smallest was £1.50. I’m grateful to everyone.

People often say they're grateful - but I really mean it. And with this membership, I'm attempting to formalise the relationship.

In July's email to SPECIAL PROJECTS members, I sought to do that by providing dates and links for exclusive livestreams and one-to-ones, and to give a preview of the year ahead:

I mention this is to emphasise how very much my own creative output has been increased by a sense of companionship, a willing audience, and a self-imposed schedule. The audience alone isn't enough - for me, anyway - and nor is the schedule. I need both.

I very much wish the same for you. So if you want to sign up for my next pop-up newsletter challenge, or other project, that's great. But this isn't a sales pitch. If you want to join SPECIAL PROJECTS, I'm sure you'll work out how. I'll be just as happy for you if you find a few friends and agree to send out a month-long pop-up newsletter (or whatever).

It's not complicated, and you don't need a vast readership: just think of Sinyavsky, who wrote three books as letters to an audience of one.

But please let me know how you get on.

.

Till next month!

John-Paul

.

Recently I posted about an experiment I’m doing – how I’m trying to stop Google, Facebook, Twitter controlling what I read. ↩

Add a comment: