terumah: moving with god

sholem aleichem,

א

I didn't grow up going to shul, really. People often assume I did. A well-meaning shul-goer the other week explained to me that, since I obviously went to Jewish day school, I probably don't understand what it is like for people who come to shul for the first time.

Quite the opposite...

We did Judaism at home, growing up. Every Friday we'd say three blessings, eat some homemade challah, and share gratitude. On Yom Kippur we made a ladder challah to help our prayers ascend, and on Rosh Hashanah we'd make a round challah for a sweet year. On Passover, we ate noodle kugel...

We spent a lot of Shabbosim at Peace Vigils after the so-called war on terror began. We went to a lot of potlucks with the Unitarian Universalists and Quakers. And we spent quite a few Sundays at Quaker Meeting, held in the local Havurah House, sitting in silence.

ב

Terumah gives instructions for building the Mishkan, the holy Dwelling. There's 96 verses in Terumah, almost all of them like this:

You are to make a curtain of blue-violet, purple, worm scarlet and twisted byssus; of designer’s making they are to make it, with winged-sphinxes. You are to put it on four columns of acacia, overlaid with gold, their hooks of gold,

on four sockets of silver, and you are to put the curtain beneath the clasps. You are to bring there, inside the curtain, the Coffer of the Testimony; the curtain shall separate for you the Holy-Shrine from the Holiest Holy-Shrine.

While the language here is beautiful, when I first started going to shul, I struggled with this perspective on holiness. If the Quakers can sit in silence for an hour, if (some) meditative traditions need nothing more than the breath -- why should we need this intricate mishkan?

Why should we need letters inked calligraphically on animal skin, rolled into a scroll, dressed in a covering, crowned with silver, paraded around the sanctuary?

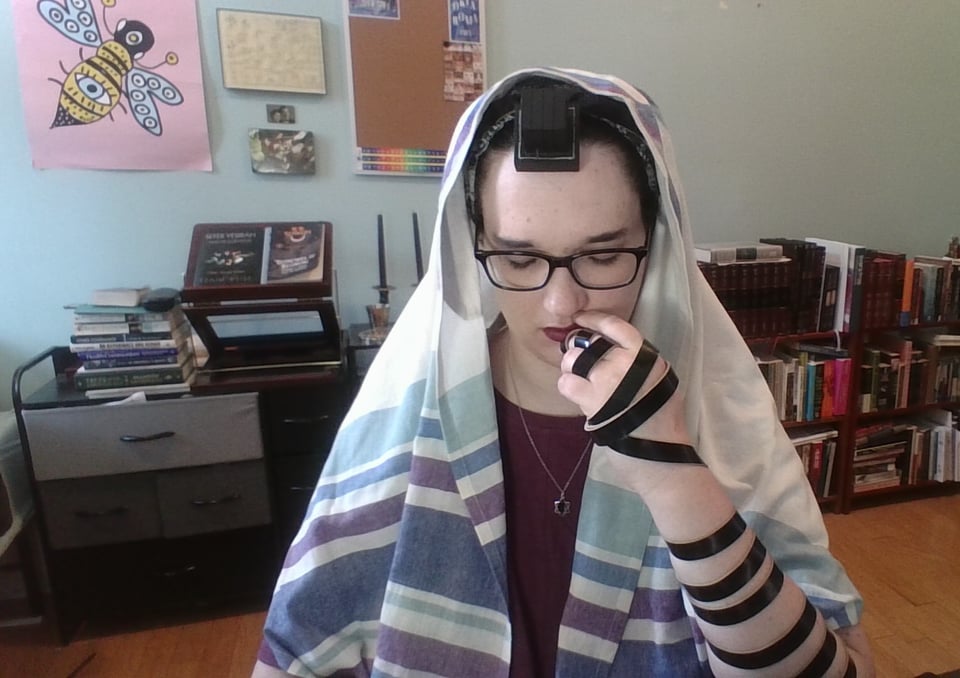

Why should we need tallis and tefillin and hundreds of words in ancient languages to pray?

ג

I've always been drawn to simplicity. I used to be one of those nerds who would tell you that well-written clean computer code was poetry. And when I chose my mathematical specialty in graduate school, I chose combinatorics, a field where you can explain cutting-edge research problems to middle-schoolers (and I have).

When I began practicing more traditional Judaism, it felt somehow inauthentic. The layers of grandeur separating us from the Torah scroll, the layers of text separating us from the original revelation, the choreography of rising and bowing and standing on tip-toes and kissing tzitzis -- these all seemed like a barrier between me and the god of truth, like layers of clothing concealing the god I met when I sat in silence and simply breathed.

ד

I'm a woman though,

ה

and womanhood and femininity are, so often, seen as mere adornments from the authentic normative experience of manhood and masculinity. Makeup, clothing, hairstyles, hormones, hair-removal, surgeries, vocal fry, vocal practice -- all of these are so often understood by misogynists as somehow inauthentic, as barriers between the outside world and our "true" selves.

Makeup is deceptive.

Fancy jewelry and clothing are frivolous.

Transition is the deepest lie of all, a sinister and manipulative concealment.

ו

Eliyahu haNavi teaches that god:

בָּעָא לְאִתְגַּלְיָיא וּלְאִתְקְרֵי בִּשְׁמָא וְאִתְלַבַּשׁ בִּלְבוּשׁ יְקָר דְּנָהִיר וּבָרָא אֵלֶּה, וְסָלִיק אֵלֶּ"ה בִּשְׁמָא

desired to reveal herself and to be called by the name, so he clothed himself in precious bright clothing and created these, and these ascended with the name

When god wanted to reveal herself, to be known, he put on clothing and created things. Precious, bright clothing. Frivolous, beautiful clothing.

ז

For all our layers, our tradition does also seek simplicity. In Masekhes Makkos, Rabbi Simlai explains that David haMelekh established the 613 mitzvos on 11 foundational mitzvos. Yeshiyahu does better, establishing the 613 on just 6.

Micah haNavi requires only three:

הגיד לך אדם מה־טוב ומה־יהוה דורש ממך כי אם־עשות משפט ואהבת חסד והצנע לכת עם־אלהיך

he has told you, human, what is good and what hashem seeks from you:

doing justice

love of loving-kindness

and hatzne’a leches with your Elokim

It isn't totally clear what hatzne'a leches means. The root of hatzne'a, which also gives us the word tznius, has something to do with covering. Modern translations read "walking in modesty with your Elokim."

I prefer to leave it partially untranslated: to move in tznius with our Elokim.

But here is what makes my heart skip a beat every time I read this passage: this mitzvah is not one we do alone. It isn't even one we do for our god Elokim.

It is a mitzvah we do with Elokim.

ח

There's only one other mitzvah like this, that I know of:

תמים תהיה עם יהוה אלהיך

tamim tihiyeh [whole you will be] with hashem your Elokim

There's a difference here. In Micah's verse, we are to move in tznius with our Elokim. Here, we are to be whole with haShem our Elokim.

The additional haShem in this second mitzvah is literally The Name, the four-letter name, the most concealed aspect of haShem, the one we cannot even speak aloud, the divine spark beyond anything we can comprehend, that which clothes itself in other names.

Come and hear more of Eliyahu haNavi's teaching:

...בְּשַׁעְתָּא דִּסְתִימָא דְכָל סְתִימִין בָּעָא לְאִתְגַּלְּיָא עֲבַד בְּרֵישָׁא נְקוּדָ"ה חֲדָא, וְדָא סָלִיק לְמֶהוֵי מַחֲשָׁבָה

When the most concealed of all that is concealed desired to reveal herself, he made first a single point, and that point arose to become a thought...the deep structure...existing and not existing, deep and hidden in the name, only called מי/who. she desired to reveal herself and to be called by the name, so he clothed himself in precious bright clothing and created אלה/these, and אלה/these ascended with the name. and these letters (אלה) joined with these (מי) in the name אלקים.

The mitzvah of being whole with haShem our Elokim is about our inner lives, about how we are and what we believe -- the Ramban says that being whole with haShem our Elokim is to

שנייחד לבבנו אליו לבדו ונאמין שהוא לבדו עושה כל

dedicate our hearts to him alone, and believe that he only does all

But reaching this inner state requires action, requires movement. This movement, I think, is the mitzvah we started with: hatzne'a leches, moving in tznius with our Elokim, moving in tznius with this name revealed in bright precious clothing.

Tznius, really, is not about being static or conforming to some set of rigid rules, it is personal and it is motion. Being tznius is about paying attention to who we are becoming, to how we want to become known, and dressing ourselves in clothing and actions that reveal that to the world and to ourselves.

Lexi Kohanski argues that, for trans people, the mitzvah of being whole with haShem makes acts of transition a mitzvah (these acts, as I understand them, are thus a movement in tznius with Elokim).

Do justice, Micah teaches.

Love lovingkindness.

And transition with your god.

ט

When Chava, the first woman, awoke after her transition from ha-adam, she met haShem.

Not as a distant, unclothed creator. Not as the most concealed of all that is concealed.

She met haShem as haShem Elokim, as Elokim reached out its hands and braided her hair:

דְּדָרֵשׁ רַבִּי שִׁמְעוֹן בֶּן מְנַסְיָא: מַאי דִּכְתִיב ״וַיִּבֶן ה׳ אלקים אֶת הַצֵּלָע״? מְלַמֵּד שֶׁקִּלְּעָהּ הַקָּדוֹשׁ בָּרוּךְ הוּא לְחַוָּה

As Rabbi Shimon ben Menasya inquired: why is it written "haShem built the tzela [that he had taken from the adam to be a woman]?" It is to teach that the Holy One, Blessed Be He braided it [her hair] for Chava.

The first woman wakes up from her transition and meets haShem Elokim, The Name clothed in the joining of two other names, clothed in precious bright clothing, as Elokim braids her hair in the garden of Eden, surrounded by rivers.

brin solomon writes:

It is dusk at the very dawning of the world, evening is gently falling in a Garden where there is no sorrow. You have just been carved out of flesh, split off from a larger being. For the first time ever, you can be — and are — alone. Naked, without language, curled up by the banks of a river while nameless birds coo and rustle overhead in the gathering night. Every sensation is fresh and overwhelming, your senses are all so raw — no one has ever experienced this before; there has never even been a before before!

And then the softest, gentlest thing: the Creator of all this vast and dazzling array drawing near, not in thunderous majesty, but with a whisper, as a breath. Not to order or command or ask tribute, but to draw back the strands of hair from your face, to work out — with infinite patience — all the tangles and knots, to weave a cord of overlapping strands…

י

I like to recreate this scene every morning. I wake up, and pull myself out of sleep. I tie my hair with a cloth, whispersinging rabbi shimon ben menasya's question

why is it written that hashem elokim built the tzela he had taken from the adam to be a woman...it comes to teach us that ha kadosh baruch hu braided her hair

כ

I still love god when I meet it in silence and stillness, in breath breathed simply and morning fog, in a few short blessings said alone by the candlelight.

But I no longer understand this as a more authentic experience of god than the god that dwells in the intricate and exacting artistry of the mishkan, in the choreography of davening, in the words inked on the torah scroll.

It is quite the opposite: this is god revealed by the clothing of human bodies and the more-than-human world, god clothed in our breath and desires and actions and creations -- and what clothing could be more intricate and complex? What clothing could reveal more?

ל

And yet. I still long for a wild Judaism. A Judaism whose practice does not require wealth spent on Judaica produced by an Orthodox industry. A Judaism we make for ourselves, in the lands we live in, with the people we love.

There is value in our insistence, as Jews, that our ritual objects be handmade according to exacting standards. But there is also loss when this process is impersonalized and industrialized, when mezuzah scrolls are flown across the world from scribes we've never met, when ritual objects made in one land are deemed more sacred than those made in others.

I'm not sure what the right balance is. But I want to be wilder. I want to move with my Elokim, I want to change.

מ

You are to make a screen for the entrance to the tent,

of blue-violet, purple, worm scarlet and twisted byssus,

of embroiderer’s making; and are to make for the screen five columns of acacia, and are to overlay them with gold, their hooks of gold, and are to cast for them five sockets of bronze.

good shabbos,

ada

p.s translations from the Torah are from Everett Fox

p.p.s. I learned the passages from the Zohar from Lexi Kohanski — my understanding and translation choices are deeply influenced by Lexi and my fellow students.

Add a comment: